Shell to Houston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LATINOS in HOUSTON Trabajando Para La Comunidad Y La Familia

VOLUME 15 • NUMBER 2 • SPRING 2018 LATINOS IN HOUSTON Trabajando para la comunidad y la familia CENTER FOR PUBLIC HISTORY LETTER FROM THE EDITOR savvy businessmen making it a commercial hub. By the What is Houston’s DNA? 1840s, Germans were coming in large numbers, as were “Discover your ethnic origins,” find other European immigrants. The numbers of Mexicans and the “source of your greatness,” trace Tejanos remained low until the 1910s-1920s, reaching about your “health, traits, and ancestry,” 5% in 1930. African Americans made up almost a quarter and “amaze yourself…find new rela- of the population, with their numbers growing during the tives.” Ads proliferate from companies Great Migration and with the influx of Creoles throughout like AncestryDNA, 23andMe, and the 1920s. MyHeritage enticing us to learn more Houston’s DNA, like the nation's, remained largely about who we really are. European due to federal laws: The Chinese Exclusion Acts Debbie Z. Harwell, People who send a saliva sample for of 1882, 1892, and 1902; the Immigration Act of 1924, which Editor analysis may be completely surprised by imposed quotas mirroring each ethnic group’s representa- the findings or even united with unknown family members. tion in the population and maintained the existing racial For others it either confirms or denies what they believed order; and the Mexican Repatriation Act of 1930, which about their heritage. For example, my AncestryDNA report permitted deportation of Mexicans — even some U.S. cit- debunks the story passed down by my mother and her izens — to relieve the stress they allegedly placed on the blonde-haired, blue-eyed siblings that their grandmother, economy. -

Walking Tour – Houston Building Stones Revised 10/2008 Neal Immega – N [email protected] Houston Gem and Mineral Society, Houston Geologic Society

Walking Tour – Houston Building Stones Revised 10/2008 Neal Immega – [email protected] Houston Gem and Mineral Society, Houston Geologic Society Start at Main Street Metro North Bound (NB) on the east side of the map ‘HoustonBuildingStones WalkingTour.gif. You need to do this tour during business hours when you can get into the buildings. The whole tour takes about 90 minutes. IBC Bank – 1001 McKinney - Just inside the bld is a lobby faced with a limestone made of stoney bryozoa. Age unknown Jesse Jones Building – JPMorgan Chase 712 Main St. – built in the old style with lots of decorative stone. Outside is scored Indiana limestone. Interior has marble and colored travertine (a flowstone deposit). Esperson Building 808 Travis, 815 Walker Town Mountain Granite from Austin, Bedford oolite, marble and serpentine (Verde Antique) http://uts.cc.utexas.edu/~rmr/tmg.html http://www.vermontmarbleandgranite.com/marble/vermont_verde_ant.htm Granite Building with Texas Star decoration – No name. Enter on the McKinney side. Back lighted onyx in escalator lobby. Basement has a Cretaceous rudist limestone and a Paleozoic stromatoporoid limestone. Wells Fargo Bank Building – flame cut poikilitic granite as pavement, zoned feldspars on the outside wall. Dynegy – 1400 Smith St. Black facing stone is a basic rock from Norway called Larvikite. http://www.toyen.uio.no/geomus/nettutstillinger/Osloriften/larvikitt-eng.html One Shell Plaza - 900 Louisiana Italian travertine. (Travertino Romano) Deposited by algae in freshwater hot springs. An inexpensive stone but a poor choice for an exterior stone. http://www.iltravertino.com/pagine/thecompany.html Houston City Hall – 901 Bagby Walls are Austin Stone (Cordova Shell) containing fossil shells. -

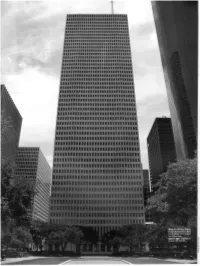

35 Years of One Shell Plaza

iiiiiilliiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiini IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII =IIB ••••••••••••••••••iiiiiiiiiini i ........ aasS§| iiiiiiimiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiui IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIBIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII /flffllfllfff IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII fllllllflllll firfiffiifin IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIRII /ifffiffifiii llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll fiifiiifiini "?ffiiiifiii 1111111111111111111111111111111 »lfffifilllii nmmun «lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll i«»ni llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll s llllllllllmmmllllllllmll IHIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIl IIIIIIIIHIIIIIIIIIHimillllll ^IIIIEPIIIll till Ellililllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll Ss lllllllllllllllllllllllltlllllll railllllllllBl^llllJIIll I '0^4 CITE 67 : SUMMER 2006 25 35 Years of One Shell Plaza Once the world's tallest concrete building, One Shell Plaza still has lessons to teach INTERVIEW W I T H J O S E P H C O L A C O BY W I L L I A M F. S T E R N A N D C H R I S T O F S P I E L E R When it wus finished m Il>7l, One Shell tin this project, research that has served beams welded together at very, very close the post modern movement came about. Plaza was the world's tallest concrete the industry well over many, many years. S[\K nig. I he World 11.ufe i enter had Before that we had basically a Miesi.m- building. The 7IS-foot, 50-story build- And then when I moved ro Houston in columns that were three-feet-four-inches type design, which some call International ing, which fills the block bounded by I4f>^, the building was just about fin- on center on the outside and a very deep Style, buildings were fairly regular. They Louisiana. Smith. Walker, and McKinney. ished. For the last 3.5 years, I have been spandrel beam. F.ssenrially, you could were rectangular, ihey prcttv much went was also Gerald D. -

Margaret Alkek Charitable Trust

Roster of Funds Donor Advised Funds Reagan & James P. Bailey, Jr. Family Fund Michelle and Lorne Bain Family Fund -A- Burke & Elizabeth Baker Family Fund: BBI Dorothy & Mickey Ables Fund Burke & Elizabeth Baker Family Fund: BHB Morrie & Rolaine Abramson Family Burke & Elizabeth Baker Family Fund: RHB Foundation Burke Baker, Jr. & Elizabeth High Baker Donor Ackerman Family Fund Advised Fund Wendy Hilty Adair Fund Pam and John Barineau Fund Ginger Adam Fund Larry & Sarah Barker Family Fund Jennifer & Tod Adam Fund Michael & Janice Barker Foundation K. S. Adams, Jr. Foundation Barringer Fund Advances in Neurological Surgery Fund John Michael Bartolotta Foundation Murari & Bidya Agrawal Family Foundation Jimmie Baskom Fund Aldrich Foundation Battier Take Charge Foundation Margaret Alkek Charitable Trust Bawcom Family Fund Chinhui & Eddie Allen Fund Beasley Family Foundation Robert & Shirley Allen Charitable Fund Bergeron-Mensay Family Charitable Fund Alpheus Charitable Fund Stephen & Linda Bickel Fund Alvis Family Foundation Bilger Family Fund Steve & Marci Alvis Foundation Bilger Family Fund II Galvin & Lolita Anciano Foundation Black Foundation Anderson Family Charitable Giving Fund Blaisdell Family Foundation D. Kent & Linda C. Anderson Foundation Elizabeth Blanchard Fund Roger and Holly Anderson Fund Susan & C. Ronald Blankenship Fund Susan & Richard Anderson Family Fund Ginger & Jack Blanton Fund Kristin & David Anthony Charitable Gift Fund Bloom Foundation Aplin Family Fund Blue Pearl Harvey Relief Fund Bruce and Lida Arendale Fund Bluegrass Fund Arneberg Family Charitable Fund Jack & Nancy Blumenthal Family Fund Ingrid V. Arneberg Charitable Fund Buddy & Denise Bolt Fund Ella Rose Arnold Fund Katy Bomar Clarity Fund Ruby Arnold Fund Bond Family Charitable Fund Arnoldy Family Fund Bosphorus Tres Fund Tim & Frances Arnoult Family Charitable Fund Polly & Murry Bowden Fund Asian American Giving Circle of Greater Karen Bowman Memorial Fund Houston Fund Bracewell & Giuliani LLP Fund Asian American Youth Giving Circle Robert S. -

Offering Summary Investment Overview

HOUSTON DOWNTOWN OFFERING SUMMARY INVESTMENT OVERVIEW HFF is pleased to offer on an exclusive basis the opportunity to acquire the fee-simple interest in the 350-room Doubletree Downtown Houston (“Property” or “Hotel”), prominently situated within Allen Center – an institutional-quality mixed-use office/retail/hotel complex – in the Houston CBD. The Hotel is strategically located near many of Houston’s top demand drivers including the George R. Brown Convention Center, Minute Maid Park (home of the Houston Astros), Toyota Center (home of the Houston Rockets) and over 51 million square feet of office space within a 1-mile radius. Many of the Fortune 500 companies located in Houston are within blocks of the Property, including Deloitte, Chevron and KBR. The Property is being offered fully unencumbered from both brand and management, presenting the next owner with a completely blank slate. With an irreplaceable location within Houston’s CBD core and strong in-place cash flow, the DoubleTree offers investors a unique, unencumbered opportunity with tremendous upside potential. INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS UNIQUE DOWNTOWN HOUSTON LOCATION The Property boasts an enviable location within Allen Center in Houston’s CBD, benefiting from downtown’s diversified demand base – not only corporate but also convention, sports, leisure, culture, medical, university/ education – and pedestrian friendly environment. This ideal mix of demand drivers has allowed the CBD to TWO ALLEN CENTER 1 MILLION SF continually outperform Houston’s overall market, as well as the -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 108 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 150 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, APRIL 1, 2004 No. 44—Part II House of Representatives TRANSPORTATION EQUITY ACT: A Mr. Chairman, I reserve the balance want to change the policy with this LEGACY FOR USERS—Continued of my time. new legislation. So this was not to b 1545 Mr. YOUNG of Alaska. Mr. Chair- side-step the courts but, rather, to man, I yield myself such time as I may keep the law the same. Now, undoubtedly, supersized trucks consume. Mr. YOUNG of Alaska. Mr. Chair- mean growing safety risks for highway I will say, though, I am usually in man, reclaiming my time, but the in- drivers and pedestrians on narrow favor of what occurs by State action, dustry or the plaintiff that filed the roads. According to the U.S. Depart- but what this amendment does, it al- suit is now being precluded from going ment of Transportation, an estimated lows the State of New Jersey to limit forth. If my colleague wants to do that, 5,000 Americans die each year in acci- large trucks and twin-trailer combina- have the court or New Jersey file an in- dents involving large trucks, and an tion trucks to the interstate system, junction against the court’s decision. additional 130,000 drivers and pas- not intrastate, the New Jersey Turn- Do not ask us to undo what a court has sengers are injured. New Jersey has a pike and the Atlantic City Expressway, ruled. -

Quarterly Market Overview 2017 Third Quarter

Quarterly Market Overview For more information, please contact: David Mendel, Public Relations Manager 2017 Third Quarter Phone: 713.629.1900 ext. 258 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE E‐mail: [email protected] HOUSTON’S OFFICE MARKET RECOVERY SLOW, INDUSTRIAL DEMAND REMAINS HIGH HOUSTON — (October 18, 2017) — Houston’s commercial real estate market is optimistic after grappling with Hurricane Harvey amid the continued energy recovery, according to quarterly market research compiled by Commercial Gateway, the commercial division of the Houston Association of Realtors (HAR). For office space, direct negative net absorption of 39,995 square feet was recorded; Class A and C showed positive absorption of 246,119 square feet and 18,230 square feet, respectively, while Class B reported negative absorption of 304,344 square feet. Move-ins at 609 Main including four different firms who preleased space in the new building accounted for almost 263,000 square feet of the Class A positive absorption. Year-to-date overall totals are positive for the year primarily due to the first quarter occupancy of 600,000 square feet by BHP Billiton in its new headquarters building, although the firm is leaving behind more than 320,000 square feet that is currently on the sublease market. Space left behind by various firms occupying new properties along with sublease spaces converting to direct space will continue to affect the vacancy rate. The current 16.7% direct vacancy rate is unchanged from last quarter, but up from the 15.5% recorded during the same quarter in 2016. Class A space overall is 16.0% vacant, Class B is 19.1% vacant and Class C is 11.4% vacant. -

'The Outstanding Building of the Year' Award!

The Newsletter for Pennzoil Place Tenants 1st & 2nd Quarter 2016 Issue Iconic Pennzoil Place Wins Local ‘The Outstanding Building of the Year’ Award! ennzoil Place is the proud winner of the 2015/2016 PHouston Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA) The Outstanding Building of the Year (TOBY) Award in the Over One Million From The Manager The From Square Feet Category. Members of hat a great time the hard working Transwestern prop- for Pennzoil Place! erty management team received the For those that may prestigious award at the Houston TOBY W not know, in January we won Award dinner in January. Houston BOMA’s local TOBY (The Outstanding Building of Each year, the TOBY is awarded to the the Year) Award! This was only highest scoring building in each of possible through the efforts in 15 categories, beginning at the local tenant programs, community level. The categories consist of five team. Judges are introduced to the score of 85, Pennzoil Place easily outreach, energy reduction, square footage awards ranging from building’s energy efficient systems, received these coveted bonus points. and environmental initiatives, under 100,000 square feet to over tenant amenities, and environmentally with great success; along with a Congratulations to the Transwestern lot of work and help from many one million square feet, along with friendly features during the tour. Pennzoil Place management team vendors and our great Pennzoil categories for medical, corporate, Among other prerequisites, each for garnering the TOBY Award. The Place tenants! A special thanks historic, low-rise and mid-rise subur- competing building must bench- team worked hard to prepare for the goes out to all team members ban office park, government, reno- mark energy usage through the EPA competition while completing dai- who contributed to winning this vated, retail, industrial office park, and year’s TOBY Award and making ENERGY STAR® website. -

Houston's Office Market Weakens Over the Quarter and Braces Itself Moving

Research & Forecast Report HOUSTON | OFFICE Q1 2020 Houston’s office market weakens over the quarter and braces itself moving forward amid $20 oil Lisa Bridges Director of Market Research | Houston Commentary by Patrick Duffy MCR Market Indicators Annual Quarterly Quarterly Colliers generally uses this space to discuss the trends we see Relative to prior period Change Change Forecast* in market data and in conversations we have with our clients, prospects and friendly competitors. We take that data and attempt VACANCY to project activity going forward. The bulk of the first quarter was, NET ABSORPTION for all practical purposes, pre-COVID. Net “move-in” data, as well as new leases signed, were likely unimpacted for Q1 based on the DELIVERIES virus or only marginally impacted. Our industry has a lead time of UNDER CONSTRUCTION at least 4-6 months before a lease is signed or space made ready for occupancy. The real impact of this COVID crisis will not present *Projected in the data until later in Q2. Inertia will carry us for a few more weeks. The world is focused on the COVID driven economic slowdown. Houston has two issues to watch – COVID and a collapse in oil prices. The oil issue is driven by Saudi Arabia and Russia failing to reach an agreement on production and by the severe decline of oil and gas demand driven by the COVID shutdown. Oil has been Summary Statistics Houston Office Market Q1 2019 Q4 2019 Q1 2020 in the low 20’s since the collision of these two events. The Energy Information Administration is projecting that supply will continue to Vacancy Rate 19.4% 19.8% 20.0% outpace demand for the balance of this year by approximately 10MM barrels per day. -

Welcome to the Texas Women's HALL of FAME 2014 PROGRAM

GCW_HOF_program_042514.indd 1 4/28/14 9:20 AM TEXAS Women’s hall of fAME Welcome to The Texas Women’s HALL OF FAME 2014 PROGRAM Welcome Carmen Pagan, Governor’s Commission for Women Chair Invocation Reverend Coby Shorter Presentation The Anita Thigpen Perry School of Nursing at Texas Tech University Keynote Address Governor Rick Perry Induction 2014 Texas Women’s Hall of Fame Honorees Closing 3 Texas Governor‘s Commission for Women GCW_HOF_program_042514.indd 2-3 4/28/14 9:20 AM TEXAS Women’s hall of fAME TEXAS Women’s hall of fAME The Texas Women’s HALL OF FAME AWARDS The Governor’s Commission for Women established the Texas Women’s Hall of Fame in 1984 to honor the remarkable achievements of Texas women while sharing their stories of great determination and innovation. The biennial awards highlight Texas women who have made significant contributions, often despite great odds. Nominations are submitted from across the state and reviewed by a panel of judges. Past honorees include first ladies, Olympic athletes and astronauts. The Texas Women’s HALL OF FAME 2014 Inductees The History of Our HALL OF FAME EXHIBIT In 2003, the Governor’s Commission for Women established a permanent exhibit for the Texas Women’s Hall of Fame on the campus of Texas Woman’s University in Denton, Texas. The exhibit features the biographies, photographs and video interviews of more than 100 notable women who have been chosen to represent the very best from our state. The exhibit is free of charge, and it is open to the public Monday through Friday from 8:00 a.m. -

MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection MSS 0093 Alfonso Vazquez

Hispanic Archival Collections Please note that not all of our Finding Aids are available online. If you would like to know about an inventory for a specific collection please call or visit the Texas Room of the Julia Ideson Building. In addition, many of our collections have a related oral history from the donor or subject of the collection. Many of these are available online via our Houston Area Digital Archive website. MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection Hector Garcia was executive director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations, Diocese of Galveston-Houston, and an officer of Harris County PASO. The Harris County chapter of the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations (PASO) was formed in October 1961. Its purpose was to advocate on behalf of Mexican Americans. Its political activities included letter-writing campaigns, poll tax drives, bumper sticker brigades, telephone banks, and community get-out-the- vote rallies. PASO endorsed candidates supportive of Mexican American concerns. It took up issues of concern to Mexican Americans. It also advocated on behalf of Mexican Americans seeking jobs, and for Mexican American owned businesses. PASO produced such Mexican American political leaders as Leonel Castillo and Ben. T. Reyes. Hector Garcia was a member of PASO and its executive secretary of the Office of Community Relations. In the late 1970's, he was Executive Director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations for the Diocese of Galveston-Houston. The collection contains some materials related to some of his other interests outside of PASO including reports, correspondence, clippings about discrimination and the advancement of Mexican American; correspondence and notices of meetings and activities of PASO (Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations of Harris County. -

2020 Annual Report Contents

2020 annual report contents 02 To Our Community: Board Chair, 22 One Team, One Community: President & CEO Letter The GHCF Way 04 GHCF By the Numbers 23 Giving Through an Equity Lens 06 Greater Houston COVID-19 24 Giving Circle Guide Recovery Fund 08 Harris County COVID-19 Relief Fund 25 GHCF Giving Guide of Houston Black-led Organizations 10 Grant Making During the Pandemic: 26 Understanding Houston The David Weekley Family Foundation 12 Supporting Organizations 28 DonorHouston Sunset 15 Center for Family Philanthropy 29 Focused Giving: The Cyvia & Melvyn Wolff Foundation 15 Family Giving Circle 32 Legacy Planning: The Margolis Family 16 The Gen Impact Fund: Alleviating 34 Pi-Squared Scholarship Child Poverty in Houston 16 Next Gen Giving Circle 35 Advisors’ Corner 17 Next Gen Best Practices for 36 Event Photos Nonprofit Board Members 18 Family Philanthropy Day 37 Governing Board 2020 20 Celebrating 25 Years of Serving 38 GHCF Staff One Community 40 Tailored Solutions for Donors HERE FOR GOOD 2020 annual report At Greater Houston Community Foundation, we have always believed in Houston’s strength and resilience, and no year has tested our grit more than 2020. While it has been a strange and uncertain time for us all, Houstonians have continued to embody what it means to be one community, and we are tremendously proud to be part of it. This year marks our 25th anniversary, and in celebration of that milestone, we selected Here for Good as our theme. We couldn’t have predicted the events of this year, but this theme is even more relevant now than it was at the beginning of the year.