Introduction the EU and the Social Legacy of the Crisis: Piecemeal Adjustment Or Room for a Paradigm Shift?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Commission

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Social Europe TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 INTRODUCTION 6 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME 6 Day 1: 3 December 2018 8 Day 2: 4 December 2018 10 SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES 20 EXHIBITION 22 THE ACCESS CITY AWARD 26 EASY-TO-READEASY-TO-READ DESCRIPTION 31 CONFERENCE PROGRAMME 31 Day 1: 3 December 2018 32 Day 2: 4 December 2018 34 EASY-TO-READEASY-TO-READ DICTIONARY 43 CONTACT INFORMATION Audio description will be available at the conference. The annual conference on the European Day of Persons Induction loops will be available in the lobby room, before entering the conference hall. with Disabilities will take place on 3-4 December 2018. Hosted by the European Commission in partnership with the European Disability Forum, this event is part of the EU’s wider efforts to promote the mainstreaming of disability issues and to raise awareness of the everyday challenges faced by persons with disabilities. Politicians, high-level experts and self-advocates will discuss the challenges, the solutions and the projects that are being prepared for improving policies for persons with disabilities. The 2018 conference will give participants the opportunity to discuss the potential shape of the next European Disability Strategy, and the ways in which it could be implemented, notably in the context of the next Multiannual Financial Framework. In 2018 we also celebrate the European Year of Cultural Heritage and this event will be an opportunity to ask ourselves about the accessibility of cultural heritage. What has been done so far and how does the EU plan to ensure that persons with disabilities can enjoy its cultural wealth on an equal basis with other citizens? How can we make sure that cultural heritage will be taken into account in the next strategy? Cultural heritage will also be an important element of this year’s Access City Award. -

Page 1 of 15 Mr Jean-Claude Juncker President European Commission Cc

Mr Jean-Claude Juncker President European Commission cc: Frans Timmermans, First Vice-President, in charge of Better Regulation, Inter-Institutional Relations, the Rule of Law and the Charter of Fundamental Rights Andrus Ansip, Vice-President for the Digital Single Market Jyrki Katainen, Vice-President for Jobs, Growth, Investment and Competitiveness Maroš Šefčovič, Vice-President for the Energy Union Vytenis Andriukaitis, Commissioner for Health and Food Safety Elžbieta Bieńkowska, Commissioner for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs Violeta Bulc, Commissioner for Transport Miguel Arias Cañete, Commissioner for Climate Action and Energy Corina Creţu, Commissioner for Regional Policy Carlos Moedas, Commissioner for Research, Science and Innovation Cecilia Malmström, Commissioner for Trade Pierre Moscovici, Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs, Taxation and Customs Tibor Navracsics, Commissioner for Education, Culture, Youth and Sport Günther Öttinger, Commissioner for Budget and Human Resources Marianne Thyssen, Commissioner for Employment, Social Affairs, Skills and Labour Mobility Karmenu Vella, Commissioner for Environment, Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Margrethe Vestager, Commissioner for Competition Brussels, 16 June 2017 Re: Contribute to economic growth and climate change mitigation through a EU Cycling Strategy Dear President Juncker, With this letter, signed by leaders from businesses, public authorities and civil society, we call upon the European Commission to unlock the potential for creating jobs -

President High Representative

First Vice-President High Representative Frans Timmermans Federica Mogherini Better Regulation, Inter-Institutional High Representative of the Union Relations, the Rule of Law and the for Foreign Affairs and Security Poli- Charter of Fundamental Rights cy / Vice-President of the PRESIDENT Commission Vice-President JEAN-CLAUDE JUNCKER Vice-President Kristalina Georgieva Andrus Ansip Vice-President Vice-President Budget & Human Resources Digital Single Market Vice-President Alenka Bratušek Valdis Dombrovskis Jyrki Katainen Energy Union Euro & Social Dialogue Jobs, Growth, Investment and Competitiveness Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Vĕra Jourová Günther Oettinger Pierre Moscovici Marianne Thyssen Corina Creţu Johannes Hahn Justice, Consumers and Gender Digital Economy & Society Economic and Financial Affairs, Employment, Social Affairs, Regional Policy European Neighbourhood Policy Equality Taxation and Customs Skills and Labour Mobility & Enlargement Negotiations Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Dimitris Avramopoulos Vytenis Andriukaitis Jonathan Hill Elżbieta Bieńkowska Miguel Arias Cañete Neven Mimica Financial Stability, Financial Services and Health & Food Safety Migration & Home Affairs Capital Markets Union Internal Market, Industry, Climate Action & Energy International Cooperation Entrepreneurship and SMEs & Development Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Margrethe Vestager Maroš Šefčovič Cecilia Malmström Karmenu Vella Competition Transport & Space Trade Environment, Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner Tibor Navracsics Carlos Moedas Phil Hogan Christos Stylianides * The HRVP may ask the Commissioner Education, Culture, Youth and Research, Science Agriculture & Humanitarian Aid & (and other commissioners) to deputise Citizenship and Innovation Rural Development Crisis Management for her in areas related to Commission competence. -

Maquetación 1

BOLETÍN DE NOTICIAS SOBRE LA UNIÓN EUROPEA BOLETIM INFORMATIVO SOBRE A UNIÃO EUROPEIA Octubre / Outubro 2014 Número 3 PORTUGAL 2020 CONVOCATÓRIAS A PARTIR DE NOVEMBRO COMISIÓN JUNKER Com a publicação, em Diário da República, do De - creto-Lei 137/2014, de 12 de setembro, o Governo El pasado día 10 de septiembre el Presidente electo de la Comisión Eu - Português estabelece o modelo de governação dos ropea, Jean-Claude Junker, presentó la nueva estructura de este ór - fundos europeus estruturais e de investimento (fun - gano de la Unión Europea que clasificó como “eficaz, dinámica, dos FEDER, FSE, Fundo de Coesão, FEADER, FEAMP, política, concebida para dar a Europa un nuevo impulso”. programas de desenvolvimento rural e programas La nueva Comisión tendrá 7 vicepresidentes que actuarán como ad - operacionais). Estabelece, também, as estruturas de juntos del Presidente y cada uno de ellos dirigirá y coordinará el trabajo apoio, monitorização, gestão, acompanhamento e de grupo concreto de comisarios cuya composición podrá cambiar en avaliação bem como as estruturas de certificação función de las necesidades y de los proyectos en desarrollo en cada auditoria e controlo. momento. Continua ... Continua... LA LITERATURA GALLEGA EN EL COMITÉ DE LAS REGIONES OTRAS NOTICIAS En una celebración de las Letras Gallegas y rindiendo homenaje a sus escritores más distinguidos, Galicia expuso en el Comité de FEDER y FSE GALICIA las Regiones una colección perteneciente al Parlamento de Ga - Disponibles las primeras versiones del Programa licia que se compone de 51 pinturas que representan las carica - Operativo del Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regio - turas de dichos escritores. Las caricaturas han sido diseñadas por nal (FEDER) y del Programa Operativo del Fondo So - Siro López y reproducidas por el escultor Ferreiro Badía en fibra cial Europeo (FSE) Galicia 2014-2020. -

Briefing January 2016 European Commission: Facts and Figures the European Commission Is the Executive Body of the European Union

Briefing January 2016 European Commission: Facts and Figures The European Commission is the executive body of the European Union. Under the Treaties, its tasks are to ‘promote the general interest of the Union’, without prejudice to individual Member States, ‘ensure the application of the Treaties’ and adopted measures, and ‘execute the budget’. It further holds a virtual monopoly on legislative initiative, as it proposes nearly all EU legislation to the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. The College of Commissioners is composed of 28 individuals. The college which came into office in November 2014 has an explicit hierarchy created through the designation by the President of seven Vice-Presidents, heading ‘project teams’ of the other 20 Commissioners. The following pages set out the responsibilities, composition and work of the Commission and its leadership, both in the current Commission and in the past. They also shed light on the staff of the Commission’s departments, their main places of employment, gender distribution and national background. Finally, they provide a breakdown of the EU’s administrative budget and budget management responsibilities. College of Commissioners 1 PRESIDENT 7 VICE-PRESIDENTS 20 COMMISSIONERS PRESIDENT Jean-Claude Juncker VICE-PRESIDENTS Frans Timmermans Federica Mogherini First Vice-President Better Regulation, Interinstitutional Relations, the Rule of Law and the Charter High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy / Vice- of Fundamental Rights President -

New European Commission Overview of Nominations by Member State

New European Commission Overview of nominations by Member State This document includes a summary of the names that have been speculated to be nominated by their national governments for the next mandate of the European Commission starting in autumn 2014. Both official nominations, as well as rumoured politicians as possible nominations are listed. Also, the desired portfolio is added for those Member States that have expressed it. Please note that official nominations by the Member States will continue over the next weeks in view of the special European Council on 30th of August, while the Commissioners will have to be vetted by the European Parliament through hearings with all nominated candidates. [Update: August 1] © European Union, 2014 List of countries: Austria Germany Poland Belgium Greece Portugal Bulgaria Hungary Romania Croatia Ireland Slovakia Cyprus Italy Slovenia Czech Republic Latvia Spain Denmark Lithuania Sweden Estonia Luxembourg United Kingdom Finland Malta France Netherlands ↑: candidates with increased possibilities Kristalina Georgieva ↑ European Commissioner Gergana Passy ex. Europe Minister Johannes Hahn Austria European Commissioner Bulgaria Sergei Stanishev MEP, ex. Prime Minister Official nomination Kristian Vigenin Foreign affairs Minister Desired portfolio: Foreign affairs Karel De Gucht European Commissioner Belgium Marianne Thyssen ↑ Neven Mimica MEP Croatia European Commissioner Didier Reynders Foreign affairs Minister Official nomination Mette Gjerskov MP, ex. Agriculture Minister Christos Stylianides Cyprus MEP Denmark Christine Antorini Education Minister Desired portfolio: Foreign affairs Czech Věra Jourová Estonia Andrus Ansip Republic Regional development Minister MEP, ex. Prime Minister Desired/possible portfolio: Desired portfolio: Transport, Regional affairs, Industry, Economic, finance Institutional relations, Digital agenda Official nomination Official nomination Jyrki Katainen Günther Oettinger Finland ex. -

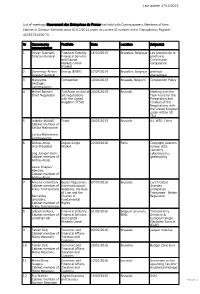

17/10/2019 List of Meetings Mouvement Des

Last update: 17/10/2019 List of meetings Mouvement des Entreprises de France has held with Commissioners, Members of their Cabinet or Director-Generals since 01/12/2014 under its current ID number in the Transparency Register: 43763731235-75. Nr Commission Portfolio Date Location Subject(s) representative 1 Olivier Guersent, Financial Stability, 16/10/2019 Bruxelles, Belgique Les priorités de la Director-General Financial Services prochaine and Capital Commission Markets Union européenne. (FISMA) 2 Dominique Ristori, Energy (ENER) 07/05/2019 Bruxelles, Belgique politique Director-General énergétique 3 Margrethe Competition 10/04/2019 Brussels, Belgium Competition Policy Vestager, Commissioner 4 Michel Barnier, Taskforce on Article 20/03/2019 Brussels Meeting with the Chief Negotiator 50 negotiations Task Force for the with the United Preparation and Kingdom (TF50) Conduct of the Negotiations with the United Kingdom under Article 50 TEU 5 Isabelle MAGNE, Trade 20/03/2019 Brussels US, WTO, China Cabinet member of Cecilia Malmström Cecilia Malmström, Commissioner 6 Andrus Ansip, Digital Single 22/09/2016 Paris Copyright, telecom Vice-President Market review, data economy, Stig Joergen Gren, cybersecurity, Cabinet member of geoblocking Andrus Ansip Laure Chapuis- Kombos, Cabinet member of Andrus Ansip 7 Antoine Colombani, Better Regulation, 07/07/2016 Brussels Lunch Debat Cabinet member of Interinstitutional Grandes Frans Timmermans Relations, the Rule Entreprises of Law and the Françaises - Better Bernardus Charter of Regulation. Smulders, -

Strengthening the European Solidarity Corps: Joint Statement by Commissioners Navracsics, Oettinger and Thyssen

European Commission - Statement Strengthening the European Solidarity Corps: Joint statement by Commissioners Navracsics, Oettinger and Thyssen Brussels, 27 June 2018 The European Parliament and the Council have reached a political agreement on the Commission's proposal to provide the European Solidarity Corps with its own budget and legal framework until 2020. Commissioner for Education, Culture, Youth and Sport, Tibor Navracsics, Commissioner for Budget and Human Resources, Günther H. Oettinger, and Commissioner for Employment, Social Affairs, Skills and Labour Mobility, Marianne Thyssen, welcomed the agreement with the following statement: "We are very pleased that the European Parliament and the Council have found a political agreement on the legal framework for the European Solidarity Corps. The European Union is built on solidarity; it is one of our fundamental values connecting European citizens. The Solidarity Corps is a key part of our efforts to empower young people and enable them to become engaged, caring members of our society, playing their part in building a resilient, cohesive Europe for the future. Since the launch of the European Solidarity Corps in December 2016, we have seen just how much interest young people have in participating in solidarity activities. So far, almost 67,000 young people have signed up, and thousands have begun volunteering, training or working in support of people and communities in need. The European Solidarity Corps is already making a difference. In central Italy, for instance, a number of volunteers from all over Europe have been, in 2017 and 2018, participating in projects helping to restore cultural heritage in regions affected by devastating earthquakes in 2016. -

28 April 2015 Mr Andrus Ansip Vice-‐President, Digital Single Market

28 April 2015 Mr Andrus Ansip Vice-President, Digital Single Market European Commission 1049 Brussels Open Letter on Ensuring Unrestricted E-Commerce: The Digital Single Market Strategy Needs To Address Online Marketplace Bans Dear Vice President Ansip, The signatories to this letter welcome the European Commission’s work on the Digital Single Market Strategy and the recently announced key areas for action. Europe stands to benefit hugely from a Digital Single Market in which e-commerce can flourish. This ultimately benefits European SMEs, consumers and digital companies alike. Unfortunately, European SMEs and consumers are currently prevented from reaping the full benefits of e-commerce. Certain manufacturers continue to prevent authorized resellers from selling their products through their shops on online marketplaces. These contractual bans are particularly detrimental to small sellers who use online marketplaces to build up a greater customer base by reaching millions of potential new customers who look for products on those marketplaces. Consumers are negatively affected as well. Banning the sale of ordinary products through online marketplaces leaves the consumer with less choice and less price transparency. This leads to higher prices. We would like to call on you to address this issue in the upcoming Digital Single Market Strategy. E-commerce in Europe will not live up to its potential if an important online distribution channel will continue to be banned by the unilateral actions of some manufacturers. In its judgment of 3 March 2011 (C 439/09 Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmétique), the CJEU already recognized that contracts which limit Internet distribution severely restrict competition. In this context, we hope the Commission’s sector inquiry into e-commerce will shed further light on these unjustified practices. -

November 2015 EU Integration Process in CEE Countries EU And

November 2015 EU integration process in EU and Liechtenstein sign new tax transparency agreement CEE countries Under the new agreement, Liechtenstein and EU Member States will automatically exchange information on the financial accounts of each other's residents from 2017, marking another important step forward in the fight against tax evasion. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-5929_en.htm Stabilisation and Association Agreement between the European Union and Kosovo signed A Stabilisation and Association Agreement (SAA) between the European Union and Kosovo was signed on October 27th in Strasbourg. The European Union will continue to support Kosovo's progress on its European path through the stabilisation and association process, the policy designed by the EU to foster cooperation with the Western Balkan countries as well as regional cooperation. Stabilisation and Association Agreements are a core component of this process. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-5928_en.htm EU must press Turkey on press freedom Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s visit to Brussels earlier this month came at an exceptionally challenging time for both Turkey and the European Union. As hundreds of thousands of refugees continue to cue up at Europe’s borders, fleeing atrocities in their homelands and encountering a continent unprepared (or unwilling) to admit their staggering numbers, the EU needs to work with Turkey toward a sustainable solution to this humanitarian crisis. https://euobserver.com/opinion/130829 Pros, advantages and Progress following Western Balkans Route Leaders' Meeting obligations resulting from Upon the initiative of President Juncker, leaders representing Albania, Austria, EU membership Bulgaria, Croatia, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Romania, Serbia and Slovenia met in Brussels at the Commission. -

Institutionalised Consensus in Europe's Parliament

Institutionalised Consensus in Europe’s Parliament Giacomo Giorgio Edward Benedetto College: London School of Economics and Political Science Thesis for the University of London Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government 1 Abstract Embedded consensus has characterised the behaviour of the European Parliament since its foundation in the 1950s. This research tests the path dependence of consensus during the period of 1994 to 2002, in the light of the changing institutional powers of the Parliament. It challenges existing theory and empirical evidence drawn mainly from roll call votes that has concluded that the European Parliament has become more competitive internally in response to increased institutional powers. There are three causal factors that reinforce consensus: the need to reconcile national and ideological divisions within a multinational political system; the pull of external institutional factors such as institutional change or the separation of powers; and internal incentives for collusion between political actors influenced by the need to accommodate the interests of the national elites present at the level of the European Union. Switzerland, a multiple cleavage system of decentralised federalism that includes consociational characteristics and a separation of powers, provides a comparative reference point for institutionalised consensus. The hypotheses of institutionalised consensus are tested empirically in four ways: 1) by roll call votes between 1994 and 2001, focusing on procedure, policy area, and the cut-off point of the 1999 elections; 2) competition and consensus in the distribution of policy-related office in the Parliament; 3) by Parliament’s use of its powers of appointment and censure over other institutions; and 4) by the internal consensus on the preparation of Parliament’s bids for greater powers when the European Union Treaties are reformed. -

High Representative and Vice-President Federica Mogherini

European Commission - Press release High Representative and Vice-President Federica Mogherini, EU Commissioners Cecilia Malmström, Marianne Thyssen and Neven Mimica reflect on progress in Bangladesh Sustainability Compact Brussels, 24 April 2015 As we mark the second anniversary since the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory complex in Bangladesh, which claimed 1,129 lives, progress on labour and safety issues has been made, while further improvements have to be achieved. This was highlighted by the Commission's Bangladesh Sustainability Compact report, published today. The EU's trade relations with Bangladesh and the importance of the ready-made garment industry to the country's development gave the EU – as by far Bangladesh's largest export market including for textiles – a special responsibility to act. Therefore, the EU forged together with Bangladesh, the US and the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the Sustainability Compact in July 2013. Since then, much progress has been made, as the Compact committed the Government of Bangladesh, in cooperation with the EU, the US, the ILO and the private sector to bring about the necessary changes in the garment sector. Federica Mogherini, High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice- President of the Commission said: "The Rana Plaza disaster will remain a dark page for Bangladesh and the international community. The Sustainability Compact has tried to bring together all partners – public and private - necessary for quick and effective action. Some progress has been achieved, but the full implementation of the Compact remains indispensable to promote labour rights and to ensure safe working conditions in Bangladesh.