Mad Max Fury Road Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Release: on Approval Motion Picture Sound Editors to Honor

For Release: On Approval Motion Picture Sound Editors to Honor George Miller with Filmmaker Award 68th MPSE Golden Reel Awards to be held as a global, virtual event on April 16th Studio City, California – February 10, 2021 – The Motion Picture Sound Editors (MPSE) will honor Academy Award-winner George Miller with its annual Filmmaker Award. The Australian writer, director and producer is responsible for some of the most successful and beloved films of recent decades including Mad Max, Mad Max 2: Road Warrior, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome and Mad Max: Fury Road. In 2007, he won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature for the smash hit Happy Feet. He also earned Oscar nominations for Babe and Lorenzo’s Oil. Miller will be presented with the MPSE FilmmaKer Award at the 68th MPSE Golden Reel Awards, set for April 16th as an international virtual event. Miller is being honored for a career noteworthy for its incredibly broad scope and consistent excellence. “George Miller redefined the action genre through his Mad Max films, and he has been just as successful in bringing us such wonderfully different films as The Witches of Eastwick, Lorenzo’s Oil, Babe and Happy Feet,” said MPSE President MarK Lanza. “He represents the art of filmmaking at its best. We are proud to present him with MPSE’s highest honor.” Miller called the award “a lovely thing,” adding, “It’s a big pat on the back. I was originally drawn to film through the visual sense, but I learned to recognize sound, emphatically, as integral to the apprehension of the story. -

HH Available Entries.Pages

Greetings! If Hollywood Heroines: The Most Influential Women in Film History sounds like a project you would like be involved with, whether on a small or large-scale level, I would love to have you on-board! Please look at the list of names below and send your top 3 choices in descending order to [email protected]. If you’re interested in writing more than one entry, please send me your top 5 choices. You’ll notice there are several women who will have a “D," “P," “W,” and/or “A" following their name which signals that they rightfully belong to more than one category. Due to the organization of the book, names have been placed in categories for which they have been most formally recognized, however, all their roles should be addressed in their individual entry. Each entry is brief, 1000 words (approximately 4 double-spaced pages) unless otherwise noted with an asterisk. Contributors receive full credit for any entry they write. Deadlines will be assigned throughout November and early December 2017. Please let me know if you have any questions and I’m excited to begin working with you! Sincerely, Laura Bauer Laura L. S. Bauer l 310.600.3610 Film Studies Editor, Women's Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal Ph.D. Program l English Department l Claremont Graduate University Cross-reference Key ENTRIES STILL AVAILABLE Screenwriter - W Director - D as of 9/8/17 Producer - P Actor - A DIRECTORS Lois Weber (P, W, A) *1500 Major early Hollywood female director-screenwriter Penny Marshall (P, A) Big, A League of Their Own, Renaissance Man Martha -

Giant Zombie Hand, Gratis Zombie Gelato and Mad Max Bootleg Art Await You at GRAPHIC This Weekend

MEDIA RELEASE TUESDAY 6 OCTOBER SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE PRESENTS Giant zombie hand, gratis zombie gelato and Mad Max bootleg art await you at GRAPHIC this weekend A giant zombie hand atop the Opera House steps. Gelato Messina’s brand new The Walking Dead ice cream flavour. Bootleg art inspired by the post-apocalyptic world of Mad Max. Get it all free at the Sydney Opera House when GRAPHIC takes over from Saturday 10 – Sunday 11 October. In the Mad Max Artist Alley the heroes, villains and wastelands of Mad Max: Fury Road will appear as reinterpreted by underground illustrators, including Sydney’s Chris Yee, James Jirat Patradoon and Georgia Hill, Melbourne’s Maddy Young and Paris’ own Ilk. The Mad Max Artist Alley, in the Concert Hall’s harbourside Northern Foyer, is co-curated by cult art collectives The Opening Hours and Goodspace, in collaboration with GRAPHIC. Looming over the Forecourt from the top of the Opera House steps, a four-metre-tall zombie hand straight out of The Walking Dead will count down to the Season 6 premiere on Sunday morning. Gelato Messina will be serving free cups of ‘Carl’s Chocolate Pudding’, the perfect blend of gruesome and delicious, from their ‘Alexandria Ice Scream’ pop-up store between midday and 4.00pm over the weekend. Since its inception in 2010, GRAPHIC has evolved into a festival like no other, commissioning and presenting new works from some of the world’s most respected artists including, but not limited to, Neil Gaiman (2010), Shaun Tan (2010), Gotye (2011), Pixar’s Lee Unkrich (2012) and Art Spiegelman (2013). -

![Arxiv:1805.06576V5 [Stat.ML] 11 Nov 2018](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1653/arxiv-1805-06576v5-stat-ml-11-nov-2018-821653.webp)

Arxiv:1805.06576V5 [Stat.ML] 11 Nov 2018

Mad Max: Affine Spline Insights into Deep Learning RANDALL BALESTRIERO, RICHARD BARANIUK Rice University, Houston, Texas, USA [email protected], [email protected] We build a rigorous bridge between deep networks (DNs) and approximation theory via spline functions and operators. Our key result is that a large class of DNs can be written as a composition of max- affine spline operators (MASOs), which provide a powerful portal through which to view and analyze their inner workings. For instance, conditioned on the input signal, the output of a MASO DN can be written as a simple affine transformation of the input. This implies that a DN constructs a set of signal- dependent, class-specific templates against which the signal is compared via a simple inner product; we explore the links to the classical theory of optimal classification via matched filters and the effects of data memorization. Going further, we propose a simple penalty term that can be added to the cost function of any DN learning algorithm to force the templates to be orthogonal with each other; this leads to significantly improved classification performance and reduced overfitting with no change to the DN architecture. The spline partition of the input signal space that is implicitly induced by a MASO directly links DNs to the theory of vector quantization (VQ) and K-means clustering, which opens up new geometric avenue to study how DNs organize signals in a hierarchical fashion. To validate the utility of the VQ interpretation, we develop and validate a new distance metric for signals and images that quantifies the difference between their VQ encodings. -

A Level Film Studies Candidate Style Answers

Qualification Accredited A LEVEL Candidate Style Answers FILM STUDIES H410 For first teaching in 2017 H410/02 Critical approaches to film Version 1 www.ocr.org.uk/filmstudies A Level Film Studies Candidate Style Answers Contents Introduction 3 Section A Question 2: Level 5 answer 4 Commentary 6 Section A Question 2: Level 3 answer 7 Commentary 7 Section B Question 4: Level 5 answer 8 Commentary 10 Section B Question 4: Level 3 answer 11 Commentary 11 Section C Question 5: Level 5 answer 12 Commentary 14 Section C Question 5: Level 3 answer 15 Commentary 16 Section C Question 7: Level 5 answer 17 Commentary 19 Section C Question 7: Level 3 answer 20 Commentary 21 Section C Question 10: Level 5 answer 22 Commentary 24 Section C Question 10: Level 3 answer 25 Commentary 25 2 © OCR 2018 A Level Film Studies Candidate Style Answers Introduction Please note that this resource is provided for advice and guidance only and does not in any way constitute an indication of grade boundaries or endorsed answers. Whilst a senior examiner has provided a possible level for each Assessment Objective when marking these answers, in a live series the mark a response would get depends on the whole process of standardisation, which considers the big picture of the year’s scripts. Therefore the level awarded here should be considered to be only an estimation of what would be awarded. How levels and marks correspond to grade boundaries depends on the Awarding process that happens after all/most of the scripts are marked and depends on a number of factors, including candidate performance across the board. -

Mad Max Tail Credits

Max Mel Gibson (Rockatansky, a cop with a Bronze badge, hence 'The Bronze') Jessie Joanne Samuel (Rockatansky) Toecutter Hugh Keays-Byrne Jim Goose Steve Bisley (Jimmy the Goose) Johnny the Boy Tim Burns Fifi Roger Ward (Captain Fifi MacAffee, aka "Fif") Cast in alphabetical order: Nurse Lisa Aldenhoven Mudguts David Bracks Clunk Bertrand Cadart Underground Mechanic David Cameron (Barry) Singer Robina Chaffey Sarse Stephen Clark Toddler Mathew Constantine Ziggy Jerry Day Station Master Reg Evans Diabando Howard Eynon Benno Max Fairchild Grinner John Farndale Senior Doctor Peter Felmingham May Swaisey Sheila Florence (sic, aka Florance) Starbuck Nic Gazzana Lair Hunter Gibb Nightrider Vince Gil (sic, aka Vincent Gill, aka Crawford Montegamo, per subtitles, also Montizano) Silvertongue Andrew Gilmore Labatouche Jonathon Hardy (sic, aka Jonathan) Sprog Brendan Heath Cundalini Paul Johnstone Grease Rat Nick Lathouris Charlie John Ley Roop Steve Millichamp Junior Doctor Phil Motherwell Scuttle George Novak Bubba Zanetti Geoff Parry Nightrider's Girl Lulu Pinkus TV Newsreader Neil Thompson Midge Billy Tisdall People's Observer Gil Tucker Girl in Chevvy Kim Sullivan with John Arnold Tom Broadbridge Peter Culpan Peter Ford Clive Hearne Telford Jackson Kristine Kaman Joan Letch Kerry Miller Janine Ogden Di Trelour Vernon Weaver Paul Young Brendan Young Associate Producer Bill Miller Editors Tony Paterson Cliff Hayes Director of Photography David Eggby Art Director Jon Dowding Asst. Art Director Steve Amezdroz Stunt Co-ordinator Grant Page Costume Designer Clare Griffin Sound Recordist Gary Wilkins Production Co-ordinator Jenny Day Special Effects Chris Murray Casting Mitch Consultancy First Assistant Director Ian Goddard Second Asst. Director Steve Connard Third Assistant Director Des Sheridan Production Asst. -

A Single Frame” Select Images from the Society of Motion Picture Still Photographers

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The SMPSP and DigitalFusion present: “A Single Frame” Select Images from the Society of Motion Picture Still Photographers On view at DigitalFusion, 3535 Hayden Avenue, Culver City, CA 90232 October 6, 2018 through Fall, 2019 9/01/2018- The SMPSP in conjunction with DigitalFusion is pleased to announce an exhibition of images shot by unit still photographers on productions around the world. “A Single Frame” spans nearly 50 years and offers a glimpse on set and behind the scenes on films such as ”Jaws” (1977), “Goodfellas” (1990), “Mad Max: Fury Road” (2015) and ”Hidden Figures” (2016), among many others. Featured are such cinema icons as Martin Scorsese, Jodie Foster, Charlize Theron, Dwayne Johnson and father-daughter Oscar winners Francis Ford Coppola and a young Sofia Coppola on the set of “Apocalypse Now.” Curated by DF Studio’s Greg Dyro and produced along with the SMPSP’s exhibition committee, this striking exhibit of 42 images explores and honors the artistry and cultural importance of unit photography. The SMPSP and DigitalFusion thank Epson for their generous sponsorship of this exhibition. About the Society of Motion Picture Still Photographers… The SMPSP was founded in Los Angeles in 1995 as a non-profit honorary organization dedicated to the art of motion picture still photography. Today, the membership includes a global roster shooting on set from LA to Rio, from Warsaw to Tehran. They share an interest in promoting the archival preservation of unit still photography and raising awareness of its intrinsic value. The organization also provides a forum for its members to exchange ideas and to examine the issues facing photographers today. -

Mad Max» Series 147-151

236 Δόξα / Докса.– 2015. – Вип. 2 (24). Δόξα / Докса.– 2015. – Вип. 2 (24). 237 5. Hardashchuk T. V. (2001) Suchasnyi ekolohizm: teoretychni zasady ta UDC 1-929.1/.3)+778.5 Konstantin Rayhert praktychni implikatsii [Modern environmentalism: the theoretical THE SOCIAL CRITICISM OF AUSTRALIAN ROADKILL foundations and practical implications], Praktychna filosofiia, № 1, pp. CULTURE IN GEORGE MILLER’S «MAD MAX» SERIES 147-151. Film series “Mad Max” is the George Miller’s social critical statement about 6. Ivanenko I. (2002) Pryroda yak zasib konstruiuvannia konfliktu v drami- the Australian car culture that is based on auto-fetishism. The Australian car feierii «Lisova pisnia» Lesi Ukrainky [Nature as a means of constructing culture is a kind of consumerism. The car murder culture, within what car is the conflict in Lesya Ukrainka’s fйerie «Forest Song»], Slobozhanshchyna, considered as a weapon of murder, is embedded into the Australian car culture. № 22, pp. 136–145. Keywords: Australia, culture, car, murder, consumerism. 7. Kontseptualni vymiry ekolohichnoi svidomosti: monohrafiia (2003) [Conceptual dimensions of environmental awareness: Monograms] / George Miller’s Mad Maxis a bright representative of Ozploitation1and [Kyselov M. M., Derkach V. L., Tolstoukhov A. V. ta in.], K., Vyd-vo the significant and emblematic film series in the history of Western popular „Parapan”, 312 p. culture. In particular the second film of the series influenced violently on Post- 8. Meterlink M. (2006) Synii ptakh: kazka [The Blue Bird: Tale] / perekazav apocalyptic thematic in cinema (for example: Lance Hool’s Steel Dawn(1987) z fr. L. Yakhnin ; per. z ros. Iu. Nadzbruchanets ; khudozh. I. Bodrova. K., starring Patrick Swayze, Lee H. -

Braveheart.Pdf

TEACHERS NOTES The ‘Braveheart’ study guide is aimed at students of GCSE Media Studies, A’ Level Film and Communication and GNVQ Media, Communication and Production, offering teachers of these courses a means of working with mainstream film. Areas of examination within the guide are narrative structure, representation, the Star, the production, and the use of special effects. These areas are essential in the study of film and media and the guide can also be used as an example for teachers of how to approach film generally. SYNOPSIS In the late 13th century, William Wallace (Mel Gibson) returns to Scotland after living away from his homeland for many years. The King of Scotland has died without an heir and the King of England, a ruthless pagan known as Edward the Longshanks, has seized the throne. Wallace becomes the leader of a ramshackle yet courageous army determined to vanquish the greater English forces. Wallace’s courage and passion unite his people in ‘Braveheart’. Following his directorial debut, ‘The Man Without a Face’, Mel Gibson is directing, producing and starring in a film combining action, intrigue and romance to tell the story of legendary Scottish knight Sir William Wallace and the love that inspired him to fight for his country’s freedom. ‘Braveheart’, dir. Mel Gibson, Twentieth Century Fox, UK release 8 September, 1995. BACKGROUND The period from about 1150 to 1350 is often called the High Middle Ages because it was in this era when medieval civilization took its fullest form. In 1066 William the Conqueror brought feudalism to England, but the early castles of that time were only wooden stockades and looked more like a Western frontier fort than our common image of a castle. -

101 Films for Filmmakers

101 (OR SO) FILMS FOR FILMMAKERS The purpose of this list is not to create an exhaustive list of every important film ever made or filmmaker who ever lived. That task would be impossible. The purpose is to create a succinct list of films and filmmakers that have had a major impact on filmmaking. A second purpose is to help contextualize films and filmmakers within the various film movements with which they are associated. The list is organized chronologically, with important film movements (e.g. Italian Neorealism, The French New Wave) inserted at the appropriate time. AFI (American Film Institute) Top 100 films are in blue (green if they were on the original 1998 list but were removed for the 10th anniversary list). Guidelines: 1. The majority of filmmakers will be represented by a single film (or two), often their first or first significant one. This does not mean that they made no other worthy films; rather the films listed tend to be monumental films that helped define a genre or period. For example, Arthur Penn made numerous notable films, but his 1967 Bonnie and Clyde ushered in the New Hollywood and changed filmmaking for the next two decades (or more). 2. Some filmmakers do have multiple films listed, but this tends to be reserved for filmmakers who are truly masters of the craft (e.g. Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick) or filmmakers whose careers have had a long span (e.g. Luis Buñuel, 1928-1977). A few filmmakers who re-invented themselves later in their careers (e.g. David Cronenberg–his early body horror and later psychological dramas) will have multiple films listed, representing each period of their careers. -

Mad Max: Fury Road Challenging Narrative and Gender Representation in the Action Genre

3 Mad Max: Fury Road Challenging Narrative and Gender Representation in the Action Genre Kyle Barrett eorge Miller redefined the ‘post- Theron), a character that at first appears threat of climate change, among Gapocalyptic’ genre with his Mad to be in league with, or at least working other predictors of doom and gloom. Max series (1979-2015). It appeared as for the antagonist, Immortan Joe (Hugh (Crewe 2016: 34) though the franchise was dead due to Keays-Byrne). However, Furiosa quickly the somewhat lacklustre response to the becomes the chief protagonist of the Miller developed and combined many concluding film of the original series,Mad narrative. This article will explore the of these fears of real-world disasters Max: Beyond Thunderdome in 1985. After key components that made the film to create his dilapidated environment. years of attempting to revive the series, a subversive text within the action/ Mad Max: The Road Warrior (1981), Mad Max: Fury Road began production post-apocalyptic genre. There will be a for instance, includes a prologue that in 2013 amongst a degree of scepticism discussion of the film’s narrative (or lack features ‘archive footage’ of a nuclear from fans of the series. Miller had moved of), Miller’s visual language and gender disaster, causing the ruin of the planet. away from post-apocalyptic worlds representation. Miller’s films also make effective use and turned ‘family-friendly’, giving us of their national landscapes, turning the adaptation of Babe (1995) and its Narrative and Genre the nightmare of the apocalypse into a underrated sequel Babe: Pig in the City The end of the world has been a site of believable reality when, ‘[ . -

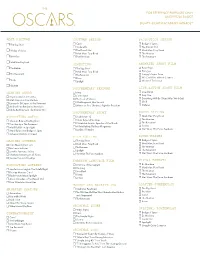

Best Picture Leading Actor Supporting Actor Leading

FOR REFERENCE PURPOSES ONLY UNOFFICIAL BALLOT EIGHTY–EIGHTH ACADEMY AWARDS ® BEST PICTURE COSTUME DESIGN PRODUCTION DESIGN ☐ The Big Short ☐ Carol ☐ Bridge of Spies ☐ Cinderella ☐ The Danish Girl ☐ Bridge of Spies ☐ The Danish Girl ☐ Mad Max: Fury Road ☐ Mad Max: Fury Road ☐ The Martian ☐ Brooklyn ☐ The Revenant ☐ The Revenant ☐ Mad Max: Fury Road DIRECTING ANIMATED SHORT FILM ☐ The Martian ☐ The Big Short ☐ Bear Story ☐ Mad Max: Fury Road ☐ Prologue ☐ The Revenant ☐ The Revenant ☐ Sanjay’s Super Team ☐ Room ☐ We Can’t Live without Cosmos Room ☐ ☐ Spotlight ☐ World of Tomorrow ☐ Spotlight DOCUMENTARY FEATURE LIVE ACTION SHORT FILM LEADING ACTOR ☐ Amy ☐ Ave Maria ☐ Day One ☐ Bryan Cranston in Trumbo ☐ Cartel Land ☐ Everything Will Be Okay (Alles Wird Gut) ☐ Matt Damon in The Martian ☐ The Look of Silence ☐ Shok ☐ Leonardo DiCaprio in The Revenant ☐ What Happened, Miss Simone? ☐ Stutterer ☐ Michael Fassbender in Steve Jobs ☐ Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight for Freedom ☐ Eddie Redmayne in The Danish Girl DOCUMENTARY SHORT SOUND EDITING SUPPORTING ACTOR ☐ Body Team 12 ☐ Mad Max: Fury Road ☐ The Martian ☐ Christian Bale in The Big Short ☐ Chau, beyond the Lines Claude Lanzmann: Spectres of the Shoah ☐ The Revenant ☐ Tom Hardy in The Revenant ☐ A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness ☐ Sicario ☐ Mark Ruffalo in Spotlight ☐ ☐ Star Wars: The Force Awakens ☐ Mark Rylance in Bridge of Spies ☐ Last Day of Freedom ☐ Sylvester Stallone in Creed FILM EDITING SOUND MIXING LEADING ACTRESS ☐ The Big Short ☐ Bridge of Spies ☐ Mad Max: Fury Road ☐