Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Happily Ever After

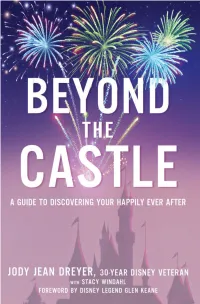

“I had a great time reading Jody’s book on her time at Disney as I have been to many of the same places and events that she attended. She went well beyond recounting her experiences though, adding many layers of texture on the how and the why of Disney storytelling. Yet Jody knows the golden rule in this business: If you knew how the trick was done, it wouldn’t be any fun anymore. At the end of the journey, she is simply in awe of the magic just as we all are, even today. Thank you, Jody, for taking us along on that journey.” – ROY P. DISNEY, grandnephew of Walt Disney “Jody may be the most organized, focused person I’ve ever met, and she has excelled in every job she’s held at the company. No one better embodies the Disney spirit.” – MICHAEL D. EISNER, former chairman and CEO of The Walt Disney Company “If Mickey Mouse and Minnie Mouse had a baby, it would be Jody Dreyer.” – DICK COOK, former chairman, Walt Disney Studios “I’m a huge believer in good storytelling. And as a fellow Disney fanatic I'm really excited to see the impact of this great read!” – KATE VOEGELE, singer/songwriter, One Tree Hill actress and recording artist on Disneymania 6 “Jody Dreyer pulls the curtain back to reveal the inner workings of one of the most fascinating and successful companies on Earth. Beyond the Castle offers incredible insight for Disney fans and business professionals alike who will relish this peek inside the magic kingdom from Jody’s unique perspective.” – DON HAHN, producer, Beauty and the Beast, The Lion King 9780310347057_UnpackingCastle_int_HC.indd 1 7/10/17 10:38 AM BEYOND THE CASTLE A GUIDE TO DISCOVERING YOUR HAPPILY EVER AFTER JODY JEAN DREYER WITH STACY WINDAHL 9780310347057_UnpackingCastle_int_HC.indd 3 7/10/17 10:38 AM ZONDERVAN Beyond the Castle Copyright © 2017 by Jody J. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Various Disney Classics Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Disney Classics mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop / Children's / Stage & Screen Album: Disney Classics Country: US Released: 2013 Style: Soundtrack, Theme, Musical MP3 version RAR size: 1692 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1570 mb WMA version RAR size: 1324 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 145 Other Formats: WAV AU MMF VQF APE AIFF VOC Tracklist Timeless Classics –Mary Moder, Dorothy Who's Afraid Of The Big, Bad Wolf (From "Three 1-1 Compton, Pinto Colvig & Billy 3:06 Little Pigs") Bletcher Whistle While You Work (From "Snow White 1-2 –Adriana Caselotti 3:24 And The Seven Dwarfs") 1-3 –Cliff Edwards When You Wish Upon A Star (From "Pinocchio") 3:13 –Cliff Edwards, Jim 1-4 Carmichael & The Hall When I See An Elephant Fly (From "Dumbo") 1:48 Johnson Choir* 1-5 –Disney Studio Chorus* Little April Shower (From "Bambi") 3:53 –Joaquin Garay, José Olivier & 1-6 Three Caballeros (From "The Three Caballeros") 2:09 Clarence Nash 1-7 –James Baskett Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah (From "Song Of The South") 2:18 Lavender Blue (Dilly Dilly) (From "So Dear To 1-8 –Burl Ives 1:02 My Heart") A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Makes (From 1-9 –Ilene Woods 4:35 "Cinderella") –Disney Studio Chorus* & All In The Golden Afternoon (From "Alice In 1-10 2:41 Kathryn Beaumont Wonderland") –Kathryn Beaumont, Bobby You Can Fly! You Can Fly! You Can Fly! (From 1-11 Driscoll, Paul Collins , Tommy 4:23 "Peter Pan") Luske & Jud Conlon Chorus* What A Dog / He's A Tramp (From "Lady And 1-12 –Peggy Lee 2:25 The Tramp") 1-13 –Mary Costa & Bill Shirley Once Upon A Dream (From "Sleeping -

Unearthing Blanche-Neige: the Making Of

Philip, Greg, and Se´bastien Roffat. "Unearthing Blanche-Neige: The making of the first made-in- Hollywood French version of Snow White and its critical reception." Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: New Perspectives on Production, Reception, Legacy. Ed. Chris Pallant and Christopher Holliday. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021. 199–216. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501351198.ch-011>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 08:53 UTC. Copyright © Chris Pallant and Christopher Holliday 2021. You may share this work for non- commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 199 11 Unearthing Blanche-Neige : The making of the first made-in- Hollywood French version of Snow White and its critical reception Greg Philip and S e´ bastien Roffat The fi rst French version of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs has never been the object of a full analysis. 1 This chapter is an attempt to present new information regarding the fi rst French dubbing made in Hollywood, alongside its production and its reception when fi rst shown in Paris on 6 May 1938. As long-time enthusiasts of the fi lm, our alternate goal was to be able to fi nd, screen and preserve that lost version. This raised several questions: What are the technical and artistic merits of this specifi c version? What was the creative process? How was it critically received? And why was this version replaced in subsequent releases? The making of the first French version In the silent era, movies were usually shot with two cameras. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Versions Title Artist Versions #1 Crush Garbage SC 1999 Prince PI SC #Selfie Chainsmokers SS 2 Become 1 Spice Girls DK MM SC (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue SF 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue MR (Don't Take Her) She's All I Tracy Byrd MM 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden SF Got 2 Stars Camp Rock DI (I Don't Know Why) But I Clarence Frogman Henry MM 2 Step DJ Unk PH Do 2000 Miles Pretenders, The ZO (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra SF 21 Guns Green Day QH SF Magdalena 21 Questions (Feat. Nate 50 Cent SC (Take Me Home) Country Toots & The Maytals SC Dogg) Roads 21st Century Breakdown Green Day MR SF (This Ain't) No Thinkin' Trace Adkins MM Thing 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard MR + 1 Martin Solveig SF 21st Century Girl Willow Smith SF '03 Bonnie & Clyde (Feat. Jay-Z SC 22 Lily Allen SF Beyonce) Taylor Swift MR SF ZP 1, 2 Step Ciara BH SC SF SI 23 (Feat. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Mike Will Made-It PH SP Khalifa And Juicy J) 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind SC 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band SG 10 Million People Example SF 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney MM 10 Minutes Until The Utilities UT 24-7 Kevon Edmonds SC Karaoke Starts (5 Min 24K Magic Bruno Mars MR SF Track) 24's Richgirl & Bun B PH 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan PH 25 Miles Edwin Starr SC 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys BS 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash SF 100 Percent Cowboy Jason Meadows PH 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago BS PI SC 100 Years Five For Fighting SC 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The MM SC SF 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris SC 26 Miles Four Preps, The SA 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters PI SC 29 Nights Danni Leigh SC 10000 Nights Alphabeat MR SF 29 Palms Robert Plant SC SF 10th Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen SG 3 Britney Spears CB MR PH 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan BS SC QH SF Len Barry DK 3 AM Matchbox 20 MM SC 1-2-3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Chapter Template

Copyright by Colleen Leigh Montgomery 2017 THE DISSERTATION COMMITTEE FOR COLLEEN LEIGH MONTGOMERY CERTIFIES THAT THIS IS THE APPROVED VERSION OF THE FOLLOWING DISSERTATION: ANIMATING THE VOICE: AN INDUSTRIAL ANALYSIS OF VOCAL PERFORMANCE IN DISNEY AND PIXAR FEATURE ANIMATION Committee: Thomas Schatz, Supervisor James Buhler, Co-Supervisor Caroline Frick Daniel Goldmark Jeff Smith Janet Staiger ANIMATING THE VOICE: AN INDUSTRIAL ANALYSIS OF VOCAL PERFORMANCE IN DISNEY AND PIXAR FEATURE ANIMATION by COLLEEN LEIGH MONTGOMERY DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN AUGUST 2017 Dedication To Dash and Magnus, who animate my life with so much joy. Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the invaluable support, patience, and guidance of my co-supervisors, Thomas Schatz and James Buhler, and my committee members, Caroline Frick, Daniel Goldmark, Jeff Smith, and Janet Staiger, who went above and beyond to see this project through to completion. I am humbled to have to had the opportunity to work with such an incredible group of academics whom I respect and admire. Thank you for so generously lending your time and expertise to this project—your whose scholarship, mentorship, and insights have immeasurably benefitted my work. I am also greatly indebted to Lisa Coulthard, who not only introduced me to the field of film sound studies and inspired me to pursue my intellectual interests but has also been an unwavering champion of my research for the past decade. -

DVD Profiler

101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure Animation Family Comedy2003 74 minG Coll.# 1 C Barry Bostwick, Jason Alexander, The endearing tale of Disney's animated classic '101 Dalmatians' continues in the delightful, all-new movie, '101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London A Martin Short, Bobby Lockwood, Adventure'. It's a fun-filled adventure fresh with irresistible original music and loveable new characters, voiced by Jason Alexander, Martin Short and S Susan Blakeslee, Samuel West, Barry Bostwick. Maurice LaMarche, Jeff Bennett, T D.Jim Kammerud P. Carolyn Bates C. W. Garrett K. SchiffM. Geoff Foster 102 Dalmatians Family 2000 100 min G Coll.# 2 C Eric Idle, Glenn Close, Gerard Get ready for outrageous fun in Disney's '102 Dalmatians'. It's a brand-new, hilarious adventure, starring the audacious Oddball, the spotless A Depardieu, Ioan Gruffudd, Alice Dalmatian puppy on a search for her rightful spots, and Waddlesworth, the wisecracking, delusional macaw who thinks he's a Rottweiler. Barking S Evans, Tim McInnerny, Ben mad, this unlikely duo leads a posse of puppies on a mission to outfox the wildly wicked, ever-scheming Cruella De Vil. Filled with chases, close Crompton, Carol MacReady, Ian calls, hilarious antics and thrilling escapes all the way from London through the streets of Paris - and a Parisian bakery - this adventure-packed tale T D.Kevin Lima P. Edward S. Feldman C. Adrian BiddleW. Dodie SmithM. David Newman 16 Blocks: Widescreen Edition Action Suspense/Thriller Drama 2005 102 min PG-13 Coll.# 390 C Bruce Willis, Mos Def, David From 'Lethal Weapon' director Richard Donner comes "a hard-to-beat thriller" (Gene Shalit, 'Today'/NBC-TV). -

Frozen and the Evolution of the Disney Heroine

It’s a Hollywood blockbuster animation that is set to become one of the most successful and beloved family films ever made. And unlike much of Disney’s past output, writes MICHELLE LAW, this film brings positive, progressive messages about gender and difference into the hearts and minds of children everywhere. SISTERS DOIN’ IT FOR THEMSELVES Frozen and the Evolution Screen Education of the Disney Heroine I No. 74 ©ATOM 16 www.screeneducation.com.au NEW & NOTABLE & NEW P MY SISTERS DOIN’ IT FOR THEMSELVES 74 No. I Screen Education 17 ince its US release in November 2013, Disney’s latest an- imated offering,Frozen (Chris Buck & Jennifer Lee), has met with critical acclaim and extraordinary box- office success. It won this year’s Academy Awards for Best Animated Feature Film and Best Original Song (for ‘Let It Go’), and despite being released less than six months Sago, it has already grossed over US$1 billion worldwide, making it the highest-earning Disney-animated film of all time. At the time of printing, the film’s soundtrack has also spent eleven non- consecutive weeks at number one on the US Billboard charts, the most held by a soundtrack since Titanic (James Cameron, 1997). Following the success of Frozen – and Tangled (Nathan Greno & Byron Howard, 2010), Disney’s adaptation of the Rapunzel story – many are antici- pating the dawn of the second Disney animation golden age. The first was what has come to be known as the Disney Renaissance, the period from the late 1980s to the late 1990s when iconic animated films such asThe Little Mermaid (Ron Clements & John Musker, 1989) and Aladdin (Ron Clements & John Musker, 1992) – films that adopted the structure and style of Broadway musicals – saved the company from financial ruin. -

The Dark Side of Hollywood

TCM Presents: The Dark Side of Hollywood Side of The Dark Presents: TCM I New York I November 20, 2018 New York Bonhams 580 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10022 24838 Presents +1 212 644 9001 bonhams.com The Dark Side of Hollywood AUCTIONEERS SINCE 1793 New York | November 20, 2018 TCM Presents... The Dark Side of Hollywood Tuesday November 20, 2018 at 1pm New York BONHAMS Please note that bids must be ILLUSTRATIONS REGISTRATION 580 Madison Avenue submitted no later than 4pm on Front cover: lot 191 IMPORTANT NOTICE New York, New York 10022 the day prior to the auction. New Inside front cover: lot 191 Please note that all customers, bonhams.com bidders must also provide proof Table of Contents: lot 179 irrespective of any previous activity of identity and address when Session page 1: lot 102 with Bonhams, are required to PREVIEW submitting bids. Session page 2: lot 131 complete the Bidder Registration Los Angeles Session page 3: lot 168 Form in advance of the sale. The Friday November 2, Please contact client services with Session page 4: lot 192 form can be found at the back of 10am to 5pm any bidding inquiries. Session page 5: lot 267 every catalogue and on our Saturday November 3, Session page 6: lot 263 website at www.bonhams.com and 12pm to 5pm Please see pages 152 to 155 Session page 7: lot 398 should be returned by email or Sunday November 4, for bidder information including Session page 8: lot 416 post to the specialist department 12pm to 5pm Conditions of Sale, after-sale Session page 9: lot 466 or to the bids department at collection and shipment. -

Primeras Páginas

ÍNDICE Prólogo ....................................................................................................... 13 Agradecimientos ........................................................................................ 17 A modo de justificación .......................................................................... 19 Introducción ............................................................................................... 21 El Departamento de Música ......................................................... 22 LAS CANCIONES DEL ESTUDIO DISNEY ......................................... 27 Cortometrajes (1928-2016) ....................................................................... 31 Mickey Mouse (1928-1953) ............................................................ 31 Silly Symphonies (1929-1939) ....................................................... 34 Donald Duck (1937-1961) .............................................................. 36 Goofy (1939-1965) ........................................................................... 39 Pluto (1937-1951) ............................................................................ 41 Cortos especiales (1938-2018) ....................................................... 42 Mediometrajes ........................................................................................... 45 Las películas de acción real ................................................................... 47 Las series de televisión ........................................................................... -

Masculinity, Fatherhood, and the Hardest Bodies in Pixar

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis or dissertation as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis or dissertation. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Signature: _____________________________ ______________ David S. Braught Date In Light of Luxo: Masculinity, Fatherhood, and the Hardest Bodies in Pixar By David S. Braught Master of Arts Film Studies _________________________________________ Matthew Bernstein Advisor _________________________________________ Michele Schreiber Committee Member _________________________________________ Eddy Von Mueller Committee Member Accepted: _________________________________________ Lisa A. Tedesco, Ph.D. Dean of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies ___________________ Date In Light of Luxo: Masculinity, Fatherhood, and the Hardest Bodies in Pixar By David S. Braught M.A., Emory University, 2010 B.A., Emory University, 2008 Advisor: Matthew Bernstein, PhD An abstract of A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the James T. Laney School of Graduate Studies of Emory University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies 2010 Abstract In Light of Luxo: Masculinity, Fatherhood, and the Hardest Bodies in Pixar By David S. -

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs RECORD CHECKLIST

Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs RECORD CHECKLIST Walt Disney Presenta Blanca Nieves Y Los Siete Enanitos 0008009 | Disney Cast | 12" Gatefold Story Teller LP | Disneyland | Argentina | 33 1/3 RPM | Walt Disney Schneewittchen Und Die Sieben Zwerge 0056.514 | Disne Cast | 12" Gatefold Story Teller LP | Disneyland | Germany | 33 1/3 RPM | Stereo Blanche Neige Et Les Sept Nains 1011-22 | Francois Perier - narrator, Jany Sylvair and Aime Doniat 1967 | 12" Standard LP | Disneyland | Canada | 33 1/3 RPM | Mono Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs 102 | Disney Cast 1975 | 12" Boxed 3-Disc LP Set | Buena Vista Records | United States | 33 1/3 RPM | Mono Walt Disney's Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs 102 | Disney Cast 1975 | 12" Boxed 3-Disc LP Set | Buena Vista Records | Australia | 33 1/3 RPM | Mono Walt Disney's Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs 102 | Disney Cast | 12" Standard 3-Disc LP Set | Buena Vista Records | Australia | 33 1/3 RPM | Mono Walt Disney Presents Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs (No. 3) 106861 | Disney Cast 1952 | 12" Standard EP | WOR Recording Division | United States | | Mono Heigh-Ho, Heigh-Ho 1072 | Mitch Miller and Orchestra - The Sandpipers | 7" Standard Single | Golden Record | United States | 45 RPM | Mono Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs 1086 | Disney Cast | 6" Standard Yellow Vinyl Single | Little Golden Records | United States | 78 RPM | Mono Fred Waring Children's Set 1-176 | Fred Waring and The Pennsyvanians | 7" Standard EP | DECCA Records | United States | 45 RPM | Mono Walt Disney's Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs 1201