Development and Validation of the Coach's Task Presentation Scale: a Quantitative Self-Report Instrument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Annotated Bibliography of Current Research in the Field of the Medical Problems of Trumpet Playing

AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY OF CURRENT RESEARCH IN THE FIELD OF THE MEDICAL PROBLEMS OF TRUMPET PLAYING D.M.A. Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School at The Ohio State University By Mark Alan Wade, B.M., M.M. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Document Committee: Professor Timothy Leasure, Adviser Approved by Professor Alan Green Dr. Russel Mikkelson ________________________ Adviser Graduate Program in Music ABSTRACT The very nature of the lifestyle of professional trumpet players is conducive to the occasional medical problem. The life-hours of diligent practice and performance that make a performer capable of musical expression on the trumpet also can cause a host of overuse and repetitive stress ailments. Other medical problems can arise through no fault of the performer or lack of technique, such as the brain disease Task-Specific Focal Dystonia. Ailments like these fall into several large categories and have been individually researched by medical professionals. Articles concerning this narrow field of research are typically published in their respective medical journals, such as the Journal of Applied Physiology . Articles whose research is pertinent to trumpet or horn, the most similar brass instruments with regard to pitch range, resistance and the intrathoracic pressures generated, are often then presented in the instruments’ respective journals, ITG Journal and The Horn Call. Most articles about the medical problems affecting trumpet players are not published in scholarly music journals such as these, rather, are found in health science publications. Herein lies the problem for both musician and doctor; the wealth of new information is not effectively available for dissemination across fields. -

Waterbury, High Player, Was Also a Member of "As Usual the •Members Have the Team

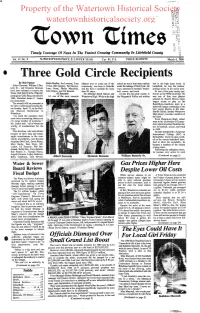

Property of the Watertown Historical Society watertownhistoricalsociety.org ffliH. tr XTown tlimes - O Timely Coverage Of News In The Fastest Growing Community In LitchfkM County o Vol. 41 No. 9 SUBSCRIPTION PRICE $12,00 PER YEAR Car. Rt.P.S. PRICE 30 CENTS March 6, ©86 Three Gold Circle Recipients By Bob Palmer 'Ralph Bradley, Joe Lovetere, 'Tony athletes ever to come' out, of the school he was a, four-letter athlete lost, in the high jump event. In Albert Zaccaria, William. JrBut- Trotta, Bill Quigley, Pat Piscopo, community, was bom, in Oakville under the tutelage of Bob Cook. He basketball, he was the Indians' terly ST., and Domenic Romano -Larry Stone, Marty Maccione, and. has been a, resident for more ' was a standout in baseball, basket- leading scorer in his senior year." have been selected, to receive the John, Regan, and, 'Ed Bennett. than, 50 years. ball, soccer, and. track. Al was a four-year varsity per- ,. Water-Oak Gold Circle of Sports' Al Zaccaria He attended South School and, Al was 'the best pole vaulter in former as 'the WHS shortstop. He prestigious Gold Ring Awards for Al, one of the most versatile Watertown High. While at the high the Naugatuck 'Valley and seldom was one of four area, players 1986, President James C. Liakos selected by Boston Braves major has •announced. league scouts to play on 'the The awards will be presented at Republican-American team in a the club's ninth, annual awards din- statewide league consisting, of the ner Sunday, April 15, at the Holi- best young players in the state. -

June 4.1986 the NCAA Comment

The NCA __June~- 4,1986, Volume 23 Number 23 Ofiicial Publication 01 the National Collegiate Athletic Association Repeal of Bill would restore medal ban deduction to donors is sought A bill has been introduced in the other than as a member of the general U.S. Senate by Sen. David Pryor, public, no gift is involved:’ Pryor The NCAA Recruiting Committee Arkansas Democrat, that calls for said. has voted to recommend to the Coun- full tax deductions on contributions “Therefore, the scholarship dona- cil that it sponsor legislation at the to athletics scholarship programs and tion is not tax-deductible under Sec- 1987 NCAA Convention to permit the revoking of previous IRS rulings tion 170 of the Internal Revenue the distribution of awards to prospec- to the contrary. Code,” Pryor said in a statement tive student-athletes at competitions Sen. Pryor submitted the legislation accompanying his bill. sponsored by member institutions. last month, calling for the application The revised ruling by the IRS says The move came in the wake of criti- of the IRS Code of 1954, allowing full the contributors can take a partial cism of an amendment to Bylaw 1-6 tax exemptions for such donations deduction if the college can provide a that was adopted at the 1986 Conven- and the repeal of an IRS ruling mod- reasonable estimate of the value of tion. ifying the exemption. the privilege extended to them. The amendment, which appears in In 1984, the IRS issued a ruling To estimate the value, the IRS says the 1986-87 NCAA Manual as Bylaw that essentially revoked prior IRS a college can consider such factors as l-6-(+0), states that no awards may determinations that such contribu- the level of demand for tickets. -

Department of Psychology University of Peshawar 2008-2009 Assessment and Treatment of Competition Anxiety Among Sportsmen and Women

ASSESSMENT AND TREATMENT OF COMPETITION ANXIETY AMONG SPORTSMEN AND WOMEN By RABIA AMJAD Supervised by: Prof. Dr. Erum Irshad Department of Psychology University of Peshawar DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR 2008-2009 ASSESSMENT AND TREATMENT OF COMPETITION ANXIETY AMONG SPORTSMEN AND WOMEN By RABIA AMJAD Supervised by: Prof. Dr. Erum Irshad Department of Psychology University of Peshawar A dissertation is submitted to the department of Psychology University of Peshawar in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN PSYCHOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR 2008-2009 In the name of ALLAH, the most Gracious, the most Merciful ASSESSMENT AND TREATMENT OF COMPETITION ANXIETY AMONG SPORTSMEN AND WOMEN ASSESSMENT AND TREATMENT OF COMPETITION ANXIETY AMONG SPORTSMEN AND WOMEN By RABIA AMJAD Approved By: Examination Committee 1. Prof. Dr. Muhammad Jahanzeb Khan 2. Dr. Asghar Ali Shah 3. Dr. Mrs. Asad Bano ______________ Supervisor ______________ Chairman DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR APPROVAL CERTIFICATE It is certified that PhD dissertation entitle “Assessment and Treatment of Competition Anxiety among Sportsmen and women” completed by Ms. Rabia Amjad has been approved for submission to the University of Peshawar, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan as partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Muhammad Jahanzeb Prof. Dr. Erum Irshad Chairman Supervisor Department of Psychology University of Peshawar Table of Contents Content No Description -

International Journal of Computer Science in Sport a Rating

International Journal of Computer Science in Sport Volume 15, Issue 2, 2016 Journal homepage: http://iacss.org/index.php?id=30 DOI: 10.1515/ijcss-2016-0006 A Rating System For Gaelic Football Teams: Factors That Influence Success Mangan, S. 1, 2,Collins, K. 1, 2 1 Institute of Technology Tallaght 2 Gaelic Sports Research Centre Abstract AIM: The current investigation aimed to create an objective rating of Gaelic football teams and to examine factors relating to a team's rating. METHOD: A modified version of the Elo Ratings formula (Elo, 1978) was used to rate Gaelic football teams. A total of 1101 competitive senior Inter County matches from 2010-2015 were incorporated into calculations. Factors examined between teams included population, registered player numbers, previous success at adult and underage levels, financial income from the GAA, team expenses and number of clubs in a county. RESULTS: The Elo Ratings formula for Gaelic football was found to have a strong predictive ability, correctly predicting the result in 72.90% of 642 matches over a 6 year period. Strong positive correlations were observed between previous success at senior level, Under 21 level, Under 18 level and current Elo points. Moderate correlations exist between population figures and current Elo points. Moderate correlations are also evident between the number of registered players in a county and the county’s Elo rating points. CONCLUSION: Gaelic football teams can be objectively rated using a modified Elo Ratings formula. In order to develop a successful senior team, counties should focus on the development of underage players, particularly up to U18 and U21 level. -

Decision Sciences Institute

Xu et al. Revenue Sharing Research: Retrospect and Future Trends REVENUE SHARING RESEARCH: A FIFTY-YEAR RETROSPECT AND FUTURE TRENDS Xun Xu, College of Business, Washington State University, Wilson Road, Pullman, WA 99164, USA. Email: [email protected], TEL: 509-715-9076. Yibai Li, Kania School of Management, The University of Scranton, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18510, USA. Email: [email protected], TEL: 646-389-4224. Lu Lu, College of Business, Washington State University, Wilson Road, Pullman, WA 99164, USA. Email: [email protected], TEL: 509-715-9692. ABSTRACT Revenue sharing is a universal phenomenon existing in many sectors (i.e. rental industry, retailing industry, governments, sports, etc.). Prior research fails to examine its cross- disciplinarity from a holistic perspective. This paper aims to close this gap by applying Latent Semantic Analysis to synthesize 183 research papers on revenue sharing in the past 50 years and describe the current research landscape. Revenue sharing research is characterized as 6 research themes which can be categorized into three contexts: (1) revenue sharing among governments, (2) revenue sharing among or within sports teams, (3) revenue sharing in supply chains. This paper compares commonalities and differences in terms of revenue sharing mechanism across the three contexts. We anticipate that revenue sharing research in supply chain will grow explosively. Keywords: Revenue Sharing, Literature Review, Text Mining, Latent Semantic Analysis, Interdisciplinary Analysis INTRODUCTION The term of Revenue Sharing is known for a seminal paper “Supply Chain Coordination with Revenue-Sharing Contracts: Strengths and Limitations” written by Cachon, Gérard P. and Lariviere, Martin A. -

Download Download

Chapter 25 Leadership Development in Sports Teams 1 2 Stewart T. Cotterill and Katrien Fransen 1AECC University College, UK 2Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium Please cite as: Cotterill, S. T., & Fransen, K. (2021). Leadership development in sports teams. In Z. Zenko & L. Jones (Eds.), Essentials of exercise and sport psychology: An open access textbook (pp. 588–612). Society for Transparency, Openness, and Replication in Kinesiology. https://doi.org/10.51224/B1025 CC-By Attribution 4.0 International This content is open access and part of Essentials of Exercise and Sport Psychology: An Open Access Textbook. All other content can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.51224/B1000 Chapter Overview In team environments the need for, and provision of leadership is a crucial factor impacting upon multiple outcomes for both teams and individuals. However, historically leadership in team sports has often developed in an ad-hoc and unstructured way. This chapter will explore the concept of leadership, particularly within the context of sports teams. Specifically exploring coach leadership, athlete leadership, and leadership development of both coaches and athletes. For correspondence: [email protected] Chapter 25: Leadership Development in Sports Teams Introduction Leadership is a core part of sport, particularly as it relates to the effectiveness of teams within sport environments (Cotterill & Fransen, 2016). The notion of leadership has been explored in detail across a wide range of environments, both within and outside of sport, which in turn has led to the development of numerous conceptualizations of leadership. Leadership has been defined and described in a variety of ways depending on the context in which it was conceptualized. -

Analysis of Hurling and Camogie Injuries

Br. J. Sp. Med; Vol 23 Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsm.23.3.183 on 1 September 1989. Downloaded from Analysis of hurling and camogie injuries P.J. Crowley', MBDCh and K.C. Condon2, FRCSI 'General Practitioner, Ovens, Co. Cork, Eire 2Consultant Plastic Surgeon, Cork Regional Hospital, Wilton, Cork, Eire In 1984, 4500 people with sport injuries attended the Cork Regional Hospital. Of these, 817 were injured in the national game of hurling and camogie. Hand injuries were the most frequent occurring in approximately one third of injured players (33 per cent) and of these, just half had a closed metacarpal fracture. Facial injuries were the second most frequent category (28 per cent). Almost one third of these were nasal fractures, while forehead and eyebrow lac- erations, fractured zygoma, loss of teeth are also common. Sport eye injuries referred to the Eye, Ear and Throat Hospital in Cork during the same period amounted to 107, of which 26 occurred in hurling. It is believed that a properly designed protective head gear would largely eliminate such facial and eye injuries. Keywords: Hurling, camogie, injuries Introduction The origin of the game hurling or camogie is lost in Irish folklore and legend. The Gaelic Athletic Associa- tion has, since 1884, laid down that it is a team game of 15 players a side and 70 minutes per game. The object http://bjsm.bmj.com/ is to drive a small hard leather ball between two posts shaped like a capital H. The ball weighs approximately 100 g and is controlled and moved by a broad-bladed stick known as a hurley. -

Chicago Bears History Custom DVD's Title Contents Super Bowl XX

Chicago Bears History Custom DVD's Title Contents Super Bowl XX Victory Parade Produced by McCaskey Family Bears at Cardinals 2006 Pregame Coverage on the team everyone thought at the time would go and Postgame Coverage undefeated and clearly beat the Cardinals. Beyond the Glory-Mike Ditka Fox Sports Net 2005 Beyond the Glory-Walter Payton Fox Sports Net 2005 49ers at Bears 1966 Custom Film created and narrated by Lindsay Stelzer using original 1966 Bears organization films NFL Replay Vikings 2006 NFL Network NFL Replay 2006 NFL Replay Buccaneers 2006 NFL Network NFL Replay 2006 NFL Replay Cardinals 2006 NFL Network NFL Replay 2006 Marlins at Cubs 2003 Game 6 Not Bears related, but DVD copy of the Bartman game 2005 Game-by-Game Comcast On Demand; 10-minute segment of each game in 2005 In Focus:1985 Bears Produced by Fox Sports Net before they left the Chicago market, using several of my game tapes 2004-2005 Chicago Bears DVD 1 Muhsin Muhammad: 6 Days to Sunday; 2004 Bears: Forging a Foundation; 2005 NFL Films Game of the Week: Bears at Lions 2004-2005 Chicago Bears DVD 2 Shuffle to the Super Bowl: 1985 Bears; 2005 Divisional Playoff Game of the Week: Flight Plan 2006 Bears DVD 1 America's Game: 1985 Bears; Championship Chase (NFL Films); Taking Flight: 2005 NFL Films Highlight 2006 Bears DVD 2 NFL Films Game of the Week: NFC Championship; Charge to the Championship (Fox 32 Chicago); 1979 George Halas interview from WTTW Chicago 2006 Bears DVD 3 Super Bowl 41 Media Day; Football in Chicago (WGN/CLTV Special 2006) 2006 Bears DVD 4 NFL Films -

Assessing the Influence of Neutral Grounds on Match Outcomes

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS IN SPORT 2018, VOL. 18, NO. 6, 892–905 https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2018.1525678 Assessing the influence of neutral grounds on match outcomes Liam Kneafsey and Stefan Müller Department of Political Science, Trinity College Dublin, Republic of Ireland ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY The home advantage in various sports has been well documented. Received 26 June 2018 So far, we lack knowledge whether playing in neutral venues Accepted 16 September 2018 indeed removes many, if not all, theoretically assumed advantages KEYWORDS of playing at home. Analysing over 3,500 senior men’s Gaelic Home advantage; neutral football and hurling matches – field games with the highest grounds; team ability; participation rates in Ireland – between 2009 and 2018, we test hurling; Gaelic football the potential moderating influence of neutral venues. In hurling and Gaelic football, a considerable share of matches is played at neutral venues. We test the influence of neutral venues based on descriptive statistics, and multilevel logistic and multinomial regressions controlling for team strength, the importance of the match, the year, and the sport. With predicted probabilities ran- ging between 0.8 and 0.9, the favourite team is very likely to win home matches. The predicted probability drops below 0.6 for away matches. At neutral venues, the favourite team has a pre- dicted probability of winning of 0.7. A Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM) approach also reveals very substantive and significant effects for the “treatment” of neutral venues. Overall, neutral venues appear to be an under-utilised option for creating fairer and less predictable competition, especially in single-game knock- out matches. -

Study on Sports Organisers' Rights in the European Union

Study on sports organisers’ rights in the European Union Final Report February 2014 Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2014 © European Union, 2014 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. HOW TO OBTAIN EU PUBLICATIONS Free publications: • one copy: via EU Bookshop (http://bookshop.europa.eu); • more than one copy or posters/maps: from the European Union’s representations (http://ec.europa.eu/represent_en.htm); from the delegations in non-EU countries (http://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/index_en.htm); by contacting the Europe Direct service (http://europa.eu/europedirect/index_en.htm) or calling 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (freephone number from anywhere in the EU) (*). (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). Priced publications: • via EU Bookshop (http://bookshop.europa.eu). Priced subscriptions: • via one of the sales agents of the Publications Office of the European Union (http://publications.europa.eu/others/agents/index_en.htm). EAC/18/2012 Study on sports organisers’ rights in the European Union T.M.C. Asser Instituut / Asser International Sports Law Centre Institute for Information Law - University of Amsterdam February 2014 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Education and Culture Directorate Youth and Sport Unit Sport This report has been prepared by the T.M.C. -

Sports in Society 1

CHAPTER Sports in Society 1 LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end of the chapter, the reader will be able to: 1. Appreciate the influence of sports and the role of sports in society 2. Understand the impact of the commercialization of sport 3. Comprehend and provide examples of the integration of sport ethics and sports law 4. Analyze the increase of violence in sports at all levels 5. Depict the influence of race in sports 6. Understand how the use of mascots in sports may relate to racial discrimination RELATED CASES Case 1.1 Harjo v. Pro-Football, Inc., 1999 TTAB LEXIS 181, 50 U.S.P.Q.2d (BNA) 1705 (Trade- mark Trial & App. Bd. Apr. 2, 1999) Case 1.2 McKichan v. St. Louis Hockey Club, L…., 967 S.W.2d 209, 1998 Mo. App. LEXIS 489 (Mo. Ct. App. 1998) Case 1.3 Popov v. Hayashi 2002 WL 31833731 (Cal. Superior 2002) Case 1.4 Bellecourt v. Cleveland 104 Ohio St.3d (Ohio 2004) Case 1.5 Cox v. National Football League 889 F. Supp. 118 (S.D. N.Y. 1995) Case 1.6 Hale V. Antoniou 2004 WL 1925551 (Me. 2004) 9781284078701_CH01_001_016.indd 1 14/12/16 10:03 am 2 Chapter 1: Sports in Society The Influence of Sports he signed a pledge at a Chicago bar in front of other fans two days before the 2007 Super Bowl promis- Sports have had a stronghold on Americans for ing to change his name to Peyton Manning if the over a century. Boys, girls, men, and women have Bears lost.