Thomas Merton and the Stranger

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Behind the Scenes: Monk's Final Case

lot, the gushing well-wishers and co- workers moving towards him, the gauntlet of handshakes and bear hugs, people drinking champagne November 23, 2009 straight out of bottles, eating red velvet cake with their bare hands, crying, embracing; a seething mass Behind The of humanity, slowly closing in. But Tony Shalhoub isn’t Scenes: Adrian Monk. Not any more. After eight years of Monk’s obsessive-compulsive hand-wiping, pole-touching and mystery-solving “Monk.” the often under-appreciated Final Case show that re-vitalized USA Network, made Shalhoub into an Emmy- By Joe Rhodes winning star and spawned a wave of quirkily-observant tv detective imitators, has finally come to an end. The final episode, because this is “Monk,” will put everything in its place. Before it ends – with a Randy Newman song written especially for the finale – loyal viewers will have the answers they’ve been waiting for: Who killed Monk’s wife, Trudy, the crime that sent him into a catatonic state and has hung over the series from the very first episode? Will he be reinstated as a San Francisco detective? Will he ever unbutton that top shirt button? Is that Captain Mr. Monk would not have enjoyed Stottlemeyer’s real hair? (Ok, not the this; the way things ended after the last one). 25th and final take of the final shot of the final season of the show that There will, of course, be bears his name. Adrian Monk, complications along the way, not the germophobic, claustrophobic, least of which is that Monk will be emotion-phobic, would have been told he has only three days to live. -

MASS TOURISM and the MEDITERRANEAN MONK SEAL

MASS TOURISM and the MEDITERRANEAN MONK SEAL The role of mass tourism in the decline and possible future extinction of Europe’s most endangered marine mammal, Monachus monachus William M. Johnson & David M. Lavigne International Marine Mammal Association 1474 Gordon Street, Guelph, Ontario, Canada N1L 1C8 ABSTRACT Mass tourism has been implicated in the decline of the Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) since the 1970s, when scientists first began reviewing the global status of the species. Since then, the scientific literature, recognising the inexorable process of disturbance and loss of habitat that this economic and social activity has produced along extensive stretches of Mediterranean coastline, has consistently identified tourism as among the most significant causes of decline affecting this critically-endangered species. Despite apparent consensus on this point, no serious attempt has been made to assess the tourist industry’s role, or to acknowledge and discuss its moral and financial responsibility, in the continuing decline and possible future extinction of M. monachus. In view of this, The Monachus Guardian 2 (2) November 1999 1 we undertook a review of existing literature to identify specific areas in which tourism has impacted the Mediterranean monk seal. Our results provide compelling evidence that mass tourism has indeed played a major role in the extirpation of the monk seal in several European countries, that it continues to act as a significant force of extinction in the last Mediterranean strongholds of the species, and that the industry exerts a generally negative influence on the design and operation of protected areas in coastal marine habitats. There are compelling reasons to conclude that unless the tourist industry can be persuaded to become an active and constructive partner in monk seal conservation initiatives, it will eventually ensure the extinction of the remaining monk seals in the Mediterranean. -

Flute Alanis Morrisette (Singer) Halle Berry (Actress) Celine Dion (Singer

Flute Trumpet Alanis Morrisette (singer) James Woods (actor) Halle Berry (actress) John Glenn (Astronaut and U.S. Senator) Celine Dion (singer) Michael Anthony (Bass player for Van Halen) Calista Flockhart (“Ally McBeal”) Drew Carey (actor/comedian) Alyssa Milano (actress) Stephen Tyler (lead singer for Aerosmith) Noah Webster (Webster’s Dictionary) Prince Charles (future King of England) Gwen Stefani (singer from No Doubt) Montel Williams (talk show host) Jennifer Garner (actress from “Alias”) Richard Gere (actor) Shania Twain (singer) Clarinet Flea (Red Hot Chili Peppers) Rainn Wilson (actor from “The Office”) Jackie Gleason (actor) Julia Roberts (actress) Samuel L. Jackson Woody Allen (actor/director) (Mace Windu from Star Wars I, II, III) Gloria Estefan (singer) Tony Shaloub (“Monk”) French Horn Eva Longoria (“Desperate Housewives”) Ewan McGregor Jimmy Kimmel (comedian/talk show host) (Obi Wan Kanobi from Star Wars I, II, III) Allan Greenspan Vanessa Williams (Singer/Actress) (former Chairman of the Federal Reserve) Otto Graham (NFL Hall of Fame quarterback) Steven Spielberg (movie director) Baritone Bass Clarinet Neil Armstrong (Astronaut - first man on the moon) Zakk Wylde (Guitarist for Ozzy Osbourne) Tuba Saxophone Andy Griffith (actor) Jennifer Garner (“Alias”) Harry Smith (CBS’s “The Early Show”) Bill Clinton (former U.S. President) Dan Aykroyd (actor) Trent Reznor (lead singer for Nine Inch Nails) Aretha Franklin (“Queen of Soul”, singer) Roy Williams (NFL Dallas Cowboys) Vince Carter (NBA Star) Percussion David Robinson (Retired NBA Star) Mike Anderson (NFL) Tedi Bruschi (NFL New England Patriots) Eddie George (retired NFL) Bob Hope (late comedian/actor) Trent Raznor (Nine Inch Nails) Lionel Richie (singer, father of Nicole Richie) Dana Carvey (actor/comedian) Tom Selleck (actor from “Magnum PI”) Vinnie Paul (Pantera) Walter Payton (NFL Hall of Fame running back) Trombone Johnny Carson (TV Host) Bill Engvall (Blue Collar Comedy Tour) Mike Piazza (former MLB catcher) Nelly Furtado (singer) Tony Stewart (NASCAR Driver) . -

Monk's Perfect Picnic Package

Attended Buffet or Family Style Service (pricing does not include rentals or staffing) For our Vegetarian & Vegan friends, there is always a very nice option to meet your dietary needs. Monk’s Perfect Picnic Package Monk’s Seasonal Salad Mixed field greens with seasonal additions of vegetables and cheese, with our balsamic vinaigrette Enjoy Our Pulled Pork and Choice of Pulled Chicken or Dry Rub Chicken Leg Quarters Choice of Two Sides Custard Filled Cornbread or Slider Buns Always includes Bread n' Butter pickles and up to three Monk’s BBQ sauce choices *Add additional sides at $3.50 per person Per Person Cost Food $19.99 Monk’s Traditional Package Monk’s Seasonal Salad Mixed field greens with seasonal additions of vegetables and cheese, with our balsamic vinaigrette Choice of three traditional meats Choice of any three side dishes* Choice of Custard Filled Cornbread or Slider Buns Always includes Bread n' Butter pickles and up to three Monk’s BBQ sauce choices *Add additional sides at $3.50 per person Monk’s Traditional Meats and Offerings Beef Brisket (smoked) Braised Chicken Thighs Dry Rub Chicken Leg Quarters (smoked) Maple Glazed Pork Loin (grilled) Pulled Chicken (brined and smoked) Pulled Pork Shoulder (smoked) Per Person Cost Food $23.99 Monk’s Premium Package Monk’s Seasonal Salad Mixed field greens with seasonal additions of vegetables and cheese, with our balsamic vinaigrette Choice of three premium meats or premium meats with combination of traditional offerings Choice of any three side dishes* Choice of Custard Filled Cornbread -

Click to Download

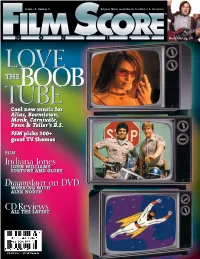

Volume 8, Number 8 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Rock On! pg. 10 LOVE thEBOOB TUBE Cool new music for Alias, Boomtown, Monk, Carnivàle, Penn & Teller’s B.S. FSM picks 100+ great great TTV themes plus Indiana Jones JO JOhN WIllIAMs’’ FOR FORtuNE an and GlORY Dragonslayer on DVD WORKING WORKING WIth A AlEX NORth CD Reviews A ALL THE L LAtEST $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 20 We Love the Boob Tube The Man From F.S.M. Video store geeks shouldn’t have all the fun; that’s why we decided to gather the staff picks for our by-no- 4 News means-complete list of favorite TV themes. Music Swappers, the By the FSM staff Emmys and more. 5 Record Label 24 Still Kicking Round-up Think there’s no more good music being written for tele- What’s on the way. vision? Think again. We talk to five composers who are 5 Now Playing taking on tough deadlines and tight budgets, and still The Man in the hat. Movies and CDs in coming up with interesting scores. 12 release. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 24 Alias Who’s writing what 25 Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! for whom. 8 The Shopping List 27 Malcolm in the Middle Recent releases worth a second look. 28 Carnivale & Monk 8 Pukas 29 Boomtown The Appleseed Saga, Part 1. FEATURES 9 Mail Bag The Last Bond 12 Fortune and Glory Letter Ever. The man in the hat is back—the Indiana Jones trilogy has been issued on DVD! To commemorate this event, we’re 24 The girl in the blue dress. -

The Midnight Assassin : Or Confession of the Monk Rinaldi

THE MIDNIGHT ASSASSIN : OR CONFESSION OF THE MONK RINALDI. CONTAINING A COMPLETE HISTORY OF HIS Diabolical Machinations and unparalleled Ferocity. TOGETHER WITH A CIRCUMSTANTIAL ACCOUNT OF THAT SCOURGE OF MANKIND THE INQUISITION; WITH THE MANNER OF BRINGING TO TRIAL THOSE UNFORTUNATE BEING WHO ARE AT ITS DISPOSAL. ---------- “ What is this secret sin, this untold take, “ That art cannot extract, nor penance cleanse?” Mysterious Mother ---------- THE SECOND EDITION. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ LONDON: Printed for T. HURST, No. 32, Paternoster-Row; And sold by J. WALLIS, and T. HUGHES, Paternoster-Row; C. CHAPLE, Pall-Mall; T. DEAN, Newgate-street; J. DINGLE, Bury; T. GIBBONS, Bath; Mr. RICHARDS, and Mr. GRAY, Plymouth; Messrs. CLARKE and Co. Manchester; & HARROR and TURNER, Nottingham. THE MIDNIGHT ASSASSIN : OR CONFESSION OF THE MONK RINALDI ----- BEFORE entering at large into our history, it will be necessary to say a few words on the manner by which it was obtained.—Some English gentlemen happening to make an excursion not far from the environs of Naples, about forty years ago, beheld a magnificent portico, the beauty of which led them to investigate the interior of the building; the church was called Santa Maria del Pianto, a very antient convent of the Black Crucifix. While standing at the portico, a person, impressive in his appearance, and lost in his own reflections, startled by the sound of their steps, quickly stole towards a door of the building, and disappeared. His tall thin figure, pale complexion, ferocious eye, and face half concealed under a long cloke, excited their attention, and, on entering the church, nobody was to be seen but a friar, who come from an adjoining convent to answer the questions of inquisitive strangers. -

There Are Many Benefits to a Sound Music Education

Famous People Who Studied Music There are many benefits to a sound music education. Ever wonder which famous people have studied music, but decided not to pursue music as a profession? Check out this list!! Flute Trumpet John Quincy Adams (6th President of the United States) John Glenn (Astronaut and U.S. Senator) Alanis Morrisette (singer) Michael Anthony (Bass player for Van Halen) Halle Berry (actress) Drew Carey (actor/comedian) Celine Dion (singer) Stephen Tyler (lead singer for Aerosmith) Alyssa Milano (actress) Prince Charles (future King of England) Noah Webster (Webster's Dictionary) Darcy Hordichuk (NHL Nashville Predators) Gwen Stephani (singer) Richard Gere (actor) Shania Twain (singer) Oboe Flea (Red Hot Chili Peppers) (All-State Player in CA) Julia Roberts (actress) Eric Lindros (Dallas Stars Forward) Samuel L. Jackson (actor) Clarinet Rainn Wilson (actor – Dwight from the Office) Trombone Julia Roberts (actress) Bill Engvall (Blue Collar Comedy Tour) Tony Shaloub ("Monk") Nelly Furtado (singer) Eva Longoria ("Desperate Housewives") Tony Stewart (NASCAR Driver) Jimmy Kimmel (comedian/talk show host) Steven Spielberg (movie director) Baritone Robert Reid (former Houston Rocket) Neil Armstrong (Astronaut…first man on the moon) Squidward Amy Acuff (US Olympic High Jumper & Model) Tuba Andy Griffith (actor) Bass Clarinet Malik Rose (NBA) Zakk Wylde (Guitarist for Ozzy Osbourne) Dan Aykroyd (actor) Aretha Franklin ("Queen of Soul", singer) Sax Jennifer Garner (Actress - "Alias") Percussion Bill Clinton (former U.S. President) -

The Role of Monk Parakeets As Nest-Site Facilitators in Their Native and Invaded Areas

biology Article The Role of Monk Parakeets as Nest-Site Facilitators in Their Native and Invaded Areas Dailos Hernández-Brito 1,* , Martina Carrete 2 , Guillermo Blanco 3, Pedro Romero-Vidal 2 , Juan Carlos Senar 4 , Emiliano Mori 5 , Thomas H. White, Jr. 6, Álvaro Luna 1,7 and José L. Tella 1 1 Department of Conservation Biology, Doñana Biological Station (CSIC), Calle Américo Vespucio 26, 41092 Sevilla, Spain; [email protected] (Á.L.); [email protected] (J.L.T.) 2 Department of Physical, Chemical and Natural Systems, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Carretera de Utrera, km 1, 41013 Sevilla, Spain; [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (P.R.-V.) 3 Department of Evolutionary Ecology, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (CSIC), José Gutiérrez Abascal 2, 28006 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 4 Museu de Ciències Naturals de Barcelona, Castell dels Tres Dragons, Parc Ciutadella, 08003 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 5 Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Istituto di Ricerca sugli Ecosistemi Terrestri, Via Madonna del Piano 10, Sesto Fiorentino, 50019 Florence, Italy; [email protected] 6 Puerto Rican Parrot Recovery Program, US Fish and Wildlife Service, P.O. Box 1600, Rio Grande, PR 00745, USA; [email protected] 7 Department of Health Sciences, Faculty of Biomedical and Health Sciences, Universidad Europea de Madrid, 28670 Madrid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Invasive species can be harmful to native species, although this fact could be more complex when some natives eventually benefit from invaders. Faced with this paradox, we show Citation: Hernández-Brito, D.; how the invasive monk parakeet, the only parrot species that builds its nests with sticks, can host Carrete, M.; Blanco, G.; Romero-Vidal, other species as tenants, increasing nest-site availability for native but also exotic species. -

{PDF} the Monk Kindle

THE MONK PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Matthew Lewis,David Stuart Davies,Kathryn White | 336 pages | 05 Aug 2009 | Wordsworth Editions Ltd | 9781840221855 | English | Herts, United Kingdom The Monk PDF Book Monk and the Genius", and episodes where the murder is related to the main plot, e. Some episodes actually start as a totally different type of case, but eventually a murder happens, e. I think it was set in a cathedral in Madrid in the 's. Upon seeing the note, Lorenzo springs into action to avenge his sister. Monk is a Mess". New York Daily News. The Doctor brought a group of Antoene warriors to Earth in order to blackmail the Monk into restoring the Doctor's timeline, the Monk faced with being killed by the Antoene for the Doctor's actions and the Doctor only willing to share his plan to stop them if the Monk restored his timeline. I would like to reemphasize what we discussed in the last chapter: That Jesus is compassionate and inclusive. Monk Goes to a Rock Concert", or "Mr. Views Read Edit View history. In his spare time, Monk continues to search for information about his wife's death and is plagued with the idea that he may never determine who killed Trudy. Retrieved January 5, Ambrosio is a famous monk; Lorenzo is a wealthy young nobleman; and Antonia is a beautiful young woman. Monk filming Locations. She eventually marries Lorenzo. The Monk was offended slightly by the suspicion, calling the Master's feud with the Doctor a grudge. She loves her daughter Antonia deeply, and dies when she attempts to protect her daughter from Ambrosio. -

Jeff Beal the Salvage Men

JEFF BEAL THE SALVAGE MEN Eric Whitacre, conductor Eric Whitacre Singers Live at Union Chapel, London TRACK LIstING THE SALVAGE MEN 1. A VERY LONG MOMENT 06:01 2. SPIDERWEB 05:05 3. VIRGA 05:48 4. AGE 04:00 5. SALVAGE 06:44 JEFF BEAL Jeff Beal is an American composer of music for film, media, and the concert hall. With musical beginnings as a jazz trumpeter and recording artist, his works are infused with an understanding of rhythm and spontaneity. Steven Schneider for the New York Times wrote of “the richness of Beal’s musical thinking...his compositions often capture the liveliness and unpredictability of the best improvisation.” Beal’s seven solo CDs, including Three Graces, Contemplations (Triloka) Red Shift (Koch Jazz), and Liberation (Island Records) established him as a respected recording artist and composer. Beal’s eclectic music has been singled out with critical acclaim and recognition. His score and theme for Netflix drama,House of Cards, have earned him several Emmy Awards, most recently in 2015. Other scores of note include his dramatic music for HBO’s acclaimed series Carnivale and Rome, as well as his comedic score and theme for the detective series, Monk. Beal composes, orchestrates, conducts, records and mixes his own scores, which gives his music a very personal, distinctive touch. Beal’s commissioned works have been performed by many leading orchestras and conductors, including the St. Louis (Marin Alsop), Rochester, Pacific (Carl St. Clair), Frankfurt, Munich, and Detroit (Neeme Jaarvi) symphony orchestras. The Salvage Men is his first choral piece written for the Eric Whitacre Singers and the Los Angeles Master Chorale. -

Nurse Aide Employment Roster Report Run Date: 9/24/2021

Nurse Aide Employment Roster Report Run Date: 9/24/2021 EMPLOYER NAME and ADDRESS REGISTRATION EMPLOYMENT EMPLOYMENT EMPLOYEE NAME NUMBER START DATE TERMINATION DATE Gold Crest Retirement Center (Nursing Support) Name of Contact Person: ________________________ Phone #: ________________________ 200 Levi Lane Email address: ________________________ Adams NE 68301 Bailey, Courtney Ann 147577 5/27/2021 Barnard-Dorn, Stacey Danelle 8268 12/28/2016 Beebe, Camryn 144138 7/31/2020 Bloomer, Candace Rae 120283 10/23/2020 Carel, Case 144955 6/3/2020 Cramer, Melanie G 4069 6/4/1991 Cruz, Erika Isidra 131489 12/17/2019 Dorn, Amber 149792 7/4/2021 Ehmen, Michele R 55862 6/26/2002 Geiger, Teresa Nanette 58346 1/27/2020 Gonzalez, Maria M 51192 8/18/2011 Harris, Jeanette A 8199 12/9/1992 Hixson, Deborah Ruth 5152 9/21/2021 Jantzen, Janie M 1944 2/23/1990 Knipe, Michael William 127395 5/27/2021 Krauter, Cortney Jean 119526 1/27/2020 Little, Colette R 1010 5/7/1984 Maguire, Erin Renee 45579 7/5/2012 McCubbin, Annah K 101369 10/17/2013 McCubbin, Annah K 3087 10/17/2013 McDonald, Haleigh Dawnn 142565 9/16/2020 Neemann, Hayley Marie 146244 1/17/2021 Otto, Kailey 144211 8/27/2020 Otto, Kathryn T 1941 11/27/1984 Parrott, Chelsie Lea 147496 9/10/2021 Pressler, Lindsey Marie 138089 9/9/2020 Ray, Jessica 103387 1/26/2021 Rodriquez, Jordan Marie 131492 1/17/2020 Ruyle, Grace Taylor 144046 7/27/2020 Shera, Hannah 144421 8/13/2021 Shirley, Stacy Marie 51890 5/30/2012 Smith, Belinda Sue 44886 5/27/2021 Valles, Ruby 146245 6/9/2021 Waters, Susan Kathy Alice 91274 8/15/2019 -

Mr. Monk & Philosophy

1HZIURP 2SHQ&RXUW 6QHDN3UHYLHZ )UHH6DPSOH &KDSWHU : : : 2 3 ( 1 & 2 8 5 7 % 2 2 . 6 & 2 0 Mr. Monk & Philosophy 9/28/09 4:16 AM Page ii Popular Culture and Philosophy ® Series Editor: George A. Reisch VOLUME 1 VOLUME 24 VOLUME 38 Seinfeld and Philosophy: A Book Bullshit and Philosophy: Radiohead and Philosophy: Fitter about Everything and Nothing Guaranteed to Get Perfect Results Happier More Deductive (2009) (2000) Every Time (2006) Edited by Brandon W. Forbes and George A. Reisch VOLUME 2 VOLUME 25 The Simpsons and Philosophy: The The Beatles and Philosophy: VOLUME 39 D’oh! of Homer (2001) Nothing You Can Think that Jimmy Buffett and Philosophy: The Can’t Be Thunk (2006) Porpoise Driven Life (2009) Edited VOLUME 3 by Erin McKenna and Scott L. Pratt The Matrix and Philosophy: VOLUME 26 Welcome to the Desert of the Real South Park and Philosophy: Bigger, VOLUME 40 (2002) Longer, and More Penetrating Transformers and Philosophy (2009) (2007) Edited by Richard Hanley Edited by John Shook and Liz VOLUME 4 Stillwaggon Swan Buffy the Vampire Slayer and VOLUME 27 Hitchcock and Philosophy: VOLUME 41 Philosophy: Fear and Trembling in Stephen Colbert and Philosophy: I Sunnydale (2003) Dial M for Metaphysics (2007) Edited by David Baggett and Am Philosophy (And So Can You!) VOLUME 5 William A. Drumin (2009) Edited by Aaron Allen Schiller The Lord of the Rings and VOLUME 28 VOLUME 42 Philosophy: One Book to Rule Them The Grateful Dead and Philosophy: Supervillains and Philosophy: All (2003) Getting High Minded about Love Sometimes, Evil Is Its Own Reward (2009) Edited by Ben Dyer VOLUME 6 and Haight (2007) Edited by Steven Baseball and Philosophy: Gimbel VOLUME 43 Thinking Outside the Batter’s Box VOLUME 29 The Golden Compass and Philosophy: (2004) Quentin Tarantino and Philosophy: God Bites the Dust (2009) Edited by How to Philosophize with a Pair of Richard Greene and Rachel Robison VOLUME 9 Harry Potter and Philosophy: Pliers and a Blowtorch (2007) VOLUME 44 If Aristotle Ran Hogwarts (2004) Edited by Richard Greene and K.