Mr. Monk & Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EUROPEAN TV DRAMA SERIES LAB Programme Application TESTIMONIALS

CONTACT www.tv-lab.eu Nadja Radojevic Head of International Training – Erich Pommer Institut [email protected] Testimonials A project by T: +49 (0)331 721 28 85 “The TV Lab’s own writers’ room became this sizzling pot F: +49 (0)331 721 28 81 Erich Pommer Institut (Germany) of focused, directed creativity, where a handful of writers Försterweg 2, 14482 Potsdam, Germany in just three days broke and created an original pilot idea The Erich Pommer Institut is one of Europe’s leading centers for www.epi-medieninstitut.de with obvious commercial and artistic potential. Most of media law, media management and media research. As a non-profit all, I was amazed on how effective it was, and how daring independent institute, our studies follow the process of media convergence through research, consultation and advanced training. you can be if you eliminate the fear of failure, and focus A project by In association with on the thrill of creation.” Each year, EPI organises and hosts around 40 seminars, workshops, Trygve Allister Diesen, Writer VARG VEUM, conferences and panels – for the European, the Canadian as well as Director KOmmissARIE WINTER, Tenk.tv, Norway the US-American media industry. TV Lab Alumni 2012 www.epi-medieninstitut.de “This kind of training is essential for Europe’s television future. It’s given me the information In association with and process I need for a wider perspective on With the support of the MEDIA 2007 Programme of the European Union what I am doing. I made crucial gains from this MediaXchange (UK) training: networking – new points of view and Based in London and LA, MediaXchange is a media consultancy helpful comparisons to my work processes.” EUROPEAN with a 20 year history assisting entertainment industry professionals Michaela Strnad, Writer PERFECT WORLD, to develop effective knowledge, contacts and business drawn from Film & Roll, Czech Republic our unique global perspective. -

Behind the Scenes: Monk's Final Case

lot, the gushing well-wishers and co- workers moving towards him, the gauntlet of handshakes and bear hugs, people drinking champagne November 23, 2009 straight out of bottles, eating red velvet cake with their bare hands, crying, embracing; a seething mass Behind The of humanity, slowly closing in. But Tony Shalhoub isn’t Scenes: Adrian Monk. Not any more. After eight years of Monk’s obsessive-compulsive hand-wiping, pole-touching and mystery-solving “Monk.” the often under-appreciated Final Case show that re-vitalized USA Network, made Shalhoub into an Emmy- By Joe Rhodes winning star and spawned a wave of quirkily-observant tv detective imitators, has finally come to an end. The final episode, because this is “Monk,” will put everything in its place. Before it ends – with a Randy Newman song written especially for the finale – loyal viewers will have the answers they’ve been waiting for: Who killed Monk’s wife, Trudy, the crime that sent him into a catatonic state and has hung over the series from the very first episode? Will he be reinstated as a San Francisco detective? Will he ever unbutton that top shirt button? Is that Captain Mr. Monk would not have enjoyed Stottlemeyer’s real hair? (Ok, not the this; the way things ended after the last one). 25th and final take of the final shot of the final season of the show that There will, of course, be bears his name. Adrian Monk, complications along the way, not the germophobic, claustrophobic, least of which is that Monk will be emotion-phobic, would have been told he has only three days to live. -

Young Adult Audiences' Perceptions of Mediated

Mediated Sexuality and Teen Pregnancy: Exploring The Secret Life Of The American Teenager A thesis submitted to the College of Communication and Information of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Nicole D. Reamer August, 2012 Thesis written by Nicole D. Reamer B.A., The University of Toledo, 2007 M.A., Kent State University, 2012 Approved by Jeffrey T. Child, Ph.D., Advisor Paul Haridakis, Ph.D., Director, School of Communication Studies Stanley T. Wearden, Ph.D., Dean, College of Communication and Information Table of Contents Page TABLE OF CONTENTS iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 TV and Socialization of Attitudes, Values, and Beliefs Among Young Adults 1 The Secret Life of the American Teenager 3 Teens, Sex, and the Media 4 II. REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE 7 Social Cognitive Theory 7 Research from a Social Cognitive Framework 11 Program-specific studies 11 Sexually-themed studies 13 Cultivation Theory 14 Research from a Cultivation perspective 16 The Adolescent Audience and Media Research 17 Sexuality in the Media 19 Alternative Media 20 Film and Television 21 Focus of this Study 27 III. METHODOLOGY 35 Sample Selection 35 Coding Procedures 36 Coder Training 37 Coding Process 39 Sexually Oriented Content 39 Overall Scene Content 40 Target 41 Location 42 Topic or Activity 43 Valence 44 Demographics 45 Analysis 46 IV. RESULTS 47 Sexually Oriented Content 47 Overall Scene Content 48 Target 48 iii Location 50 Topic or Activity 51 Valence 52 Topic Valence Variation by Target 54 V. DISCUSSION 56 Summary of Findings and Implications 58 Target and Location 59 Topic and Activity 63 Valence 65 Study Limitations 67 Future Directions 68 Audience Involvement 69 Conclusion 71 APPENDICES A. -

FRIDAY the 13TH: the MICROS PLAY MONK (Cuneiform Rune 310)

Bio information: THE MICROSCOPIC SEPTET Title: FRIDAY THE 13TH: THE MICROS PLAY MONK (Cuneiform Rune 310) Cuneiform promotion dept: (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American radio) http://www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / THELONIOUS MONK / THE MICROSCOPIC SEPTET “If the Micros have a spiritual beacon, it’s Thelonious Monk. Like the maverick bebop pianist, they persevere... Their expanding core audience thrives on the group’s impeccable arrangements, terse, angular solos, and devil-may-care attitude. But Monk and the Micros have something else in common as well. Johnston tells a story: “Someone once walked up to Monk and said, “You know, Monk, people are laughing at your music.’ Monk replied, ‘Let ‘em laugh. People need to laugh a little more.” – Richard Gehr, Newsday, New York 1989 “There is immense power and careful logic in the music of Thelonious Sphere Monk. But you might have such a good time listening to it that you might not even notice. …His tunes… warmed the heart with their odd angles and bright colors. …he knew exactly how to make you feel good… The groove was paramount: When you’re swinging, swing some more,” he’d say...” – Vijay Iyer, “Ode to a Sphere,” JazzTimes, 2010 “When I replace Letterman… The band I'm considering…is the Microscopic Septet, a New York saxophone-quartet-plus-rhythm whose riffs do what riffs are supposed to do: set your pulse racing and lodge in your skull for days on end. … their humor is difficult to resist. -

Jon's Mini-Codiums and More 2016

Jon's Mini-codiums and More 2016 I want to thank all of the people that ordered bulbs from me last year. This was my first time getting orders filled and it was a learning experience. After many years of drought conditions in California, it finally rained. Here in the San Francisco Bay Area, we had ample amounts of rain. My daffodils were very happy. My earliest daffodils (fall flowering species such as N. virdiflorus, N. miniatus, and N. serotinus, and fall flowering bulbocodiums bloomed.) started blooming in October 2015. More fall bloomers flowered (fall blooming cultivars, tazettas, bulbocodiums which included N. cantabricus, N. romieuxii, and Division 10 cultivars) in November and December. Many of the late winter / early spring bloomers (particularly the miniatures in Division 1, 2, 6, 9, 10, 11, and 12) grew vigorously and bloomed during the months of January through early March. The season was going to be early again. During the end of February and first week of March, I was in Arizona on vacation (went to baseball spring training), and upon our return home, it stormed and noticed that most of the miniatures that were coming Spring Serenade into bloom were ravaged by the heavy winds, rain, 5 Y-Y and pests. A few days before the Northern California Daffodil Chapter’s Murphys Show (on March 19 and 20), I was able to bring a small number of miniatures to the show. The next week, I was able to bring many of my late flowering miniatures to the Fortuna Show. Nancy and Jerry Wilson attended the show. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Mr Monk on Patrol Kindle

MR MONK ON PATROL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lee Goldberg | 278 pages | 05 Jul 2012 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780451236647 | English | New York, United States Mr. Monk Is a Mess - Wikipedia I'm a sucker for these books. Look down your nose if you must, but I like the character of Adrian Monk and I enjoy veteran TV mystery writer, Lee Goldberg's take on the continuing and ever evolving, Monkverse. Apparently this is the penultimate Mr. Monk book. Goldberg uses Monk's long-suffering assistant, Natalie as the narrator of his books. Unlike most expanded universe tie-in books, he calls back characters and events from previous books and TV episodes, weaves a decent mystery and moves the g I'm a sucker for these books. Unlike most expanded universe tie-in books, he calls back characters and events from previous books and TV episodes, weaves a decent mystery and moves the growth of the characters forward. This is probably the part I most enjoy. The book begins with a fun mystery an excerpt of which was published as a short in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, and shortlisted for an Edgar Award. Things aren't going well. Well, they are, sort of. Apparently hired in part because of a reputation as a competent, but ridiculous cop, the folks who hired him didn't count on how personable, earnest and hard-working Disher is or his uncanny ability to literally stumble into mysteries. Disher found and reported rampant, years-long corruption in the Summit city government. This lead to the resignation of the mayor and most of the town council. -

"Art" Monk Years

Name: James Arthur "Art" Monk Years: December 5, 1957 to Present Residence: White Plains, New York Brief Biography: Born in White Plains, Art Monk had a passion for sports and particularly excelled in football while attending White Plains High School. With good grades and the support of his coach, Monk won a full scholarship to Syracuse University. At Syracuse University, Monk was a four-year Orangemen letter winner (1976-79). He led the team in receiving in 1977, 1978 and 1979 and still ranks in the top 10 on several school career record lists, including career receptions (sixth), all-time receiving yards (seventh) and receiving yards per game (ninth). Monk was drafted in the first round of the 1980 NFL Draft by the Washington Redskins. During his rookie year, Monk was a unanimous All-Rookie selection and set a new Redskins rookie record, with 58 receptions. In 1984, Monk caught an NFL record 106 receptions for a career-best 1,372 yards. He caught eight or more passes in six games, had five games of 100 yards or more, and in a game against the San Francisco 49ers caught ten passes for 200 yards, earning him team MVP honors and his first Pro Bowl selection. Monk went over the 1,000-yard mark in each of the following two seasons, becoming the first Redskins receiver to produce three consecutive 1,000 yard seasons. He also became the first Redskins player to catch 70 or more passes in three consecutive seasons. During Monk's 14 seasons with the Redskins, the team won three Super Bowls (XVII, XXII, and XXVI) and had only three losing seasons. -

Summer 2019 Vol.21, No.3 Screenwriter Film | Television | Radio | Digital Media

CANADIAN CANADA $7 SUMMER 2019 VOL.21, NO.3 SCREENWRITER FILM | TELEVISION | RADIO | DIGITAL MEDIA A Rock Star in the Writers’ Room: Bringing Jann Arden to the small screen Crafting Canadian Horror Stories — and why we’re so good at it Celebrating the 23rd annual WGC Screenwriting Awards Emily Andras How she turned PM40011669 Wynonna Earp into a fan phenomenon Congratulations to Emily Andras of SPACE’s Wynonna Earp, Sarah Dodd of CTV’s Cardinal, and all of the other 2019 WGC Screenwriting Award winners. Proud to support Canada’s creative community. CANADIAN SCREENWRITER The journal of the Writers Guild of Canada Vol. 21 No. 3 Summer 2019 ISSN 1481-6253 Publication Mail Agreement Number 400-11669 Publisher Maureen Parker Editor Tom Villemaire [email protected] Contents Director of Communications Lana Castleman Cover Editorial Advisory Board There’s #NoChill When it Comes Michael Amo to Emily Andras’s Wynonna Earp 6 Michael MacLennan How 2019’s WGC Showrunner Award winner Emily Susin Nielsen Andras and her room built a fan and social media Simon Racioppa phenomenon — and why they’re itching to get back in Rachel Langer the saddle for Wynonna’s fourth season. President Dennis Heaton (Pacific) By Li Robbins Councillors Michael Amo (Atlantic) Features Mark Ellis (Central) What Would Jann Do? 12 Marsha Greene (Central) That’s exactly the question co-creators Leah Gauthier Alex Levine (Central) and Jennica Harper asked when it came time to craft a Anne-Marie Perrotta (Quebec) heightened (and hilarious) fictional version of Canadian Andrew Wreggitt (Western) icon Jann Arden’s life for the small screen. -

MASS TOURISM and the MEDITERRANEAN MONK SEAL

MASS TOURISM and the MEDITERRANEAN MONK SEAL The role of mass tourism in the decline and possible future extinction of Europe’s most endangered marine mammal, Monachus monachus William M. Johnson & David M. Lavigne International Marine Mammal Association 1474 Gordon Street, Guelph, Ontario, Canada N1L 1C8 ABSTRACT Mass tourism has been implicated in the decline of the Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus) since the 1970s, when scientists first began reviewing the global status of the species. Since then, the scientific literature, recognising the inexorable process of disturbance and loss of habitat that this economic and social activity has produced along extensive stretches of Mediterranean coastline, has consistently identified tourism as among the most significant causes of decline affecting this critically-endangered species. Despite apparent consensus on this point, no serious attempt has been made to assess the tourist industry’s role, or to acknowledge and discuss its moral and financial responsibility, in the continuing decline and possible future extinction of M. monachus. In view of this, The Monachus Guardian 2 (2) November 1999 1 we undertook a review of existing literature to identify specific areas in which tourism has impacted the Mediterranean monk seal. Our results provide compelling evidence that mass tourism has indeed played a major role in the extirpation of the monk seal in several European countries, that it continues to act as a significant force of extinction in the last Mediterranean strongholds of the species, and that the industry exerts a generally negative influence on the design and operation of protected areas in coastal marine habitats. There are compelling reasons to conclude that unless the tourist industry can be persuaded to become an active and constructive partner in monk seal conservation initiatives, it will eventually ensure the extinction of the remaining monk seals in the Mediterranean. -

Flute Alanis Morrisette (Singer) Halle Berry (Actress) Celine Dion (Singer

Flute Trumpet Alanis Morrisette (singer) James Woods (actor) Halle Berry (actress) John Glenn (Astronaut and U.S. Senator) Celine Dion (singer) Michael Anthony (Bass player for Van Halen) Calista Flockhart (“Ally McBeal”) Drew Carey (actor/comedian) Alyssa Milano (actress) Stephen Tyler (lead singer for Aerosmith) Noah Webster (Webster’s Dictionary) Prince Charles (future King of England) Gwen Stefani (singer from No Doubt) Montel Williams (talk show host) Jennifer Garner (actress from “Alias”) Richard Gere (actor) Shania Twain (singer) Clarinet Flea (Red Hot Chili Peppers) Rainn Wilson (actor from “The Office”) Jackie Gleason (actor) Julia Roberts (actress) Samuel L. Jackson Woody Allen (actor/director) (Mace Windu from Star Wars I, II, III) Gloria Estefan (singer) Tony Shaloub (“Monk”) French Horn Eva Longoria (“Desperate Housewives”) Ewan McGregor Jimmy Kimmel (comedian/talk show host) (Obi Wan Kanobi from Star Wars I, II, III) Allan Greenspan Vanessa Williams (Singer/Actress) (former Chairman of the Federal Reserve) Otto Graham (NFL Hall of Fame quarterback) Steven Spielberg (movie director) Baritone Bass Clarinet Neil Armstrong (Astronaut - first man on the moon) Zakk Wylde (Guitarist for Ozzy Osbourne) Tuba Saxophone Andy Griffith (actor) Jennifer Garner (“Alias”) Harry Smith (CBS’s “The Early Show”) Bill Clinton (former U.S. President) Dan Aykroyd (actor) Trent Reznor (lead singer for Nine Inch Nails) Aretha Franklin (“Queen of Soul”, singer) Roy Williams (NFL Dallas Cowboys) Vince Carter (NBA Star) Percussion David Robinson (Retired NBA Star) Mike Anderson (NFL) Tedi Bruschi (NFL New England Patriots) Eddie George (retired NFL) Bob Hope (late comedian/actor) Trent Raznor (Nine Inch Nails) Lionel Richie (singer, father of Nicole Richie) Dana Carvey (actor/comedian) Tom Selleck (actor from “Magnum PI”) Vinnie Paul (Pantera) Walter Payton (NFL Hall of Fame running back) Trombone Johnny Carson (TV Host) Bill Engvall (Blue Collar Comedy Tour) Mike Piazza (former MLB catcher) Nelly Furtado (singer) Tony Stewart (NASCAR Driver) . -

Monk's Perfect Picnic Package

Attended Buffet or Family Style Service (pricing does not include rentals or staffing) For our Vegetarian & Vegan friends, there is always a very nice option to meet your dietary needs. Monk’s Perfect Picnic Package Monk’s Seasonal Salad Mixed field greens with seasonal additions of vegetables and cheese, with our balsamic vinaigrette Enjoy Our Pulled Pork and Choice of Pulled Chicken or Dry Rub Chicken Leg Quarters Choice of Two Sides Custard Filled Cornbread or Slider Buns Always includes Bread n' Butter pickles and up to three Monk’s BBQ sauce choices *Add additional sides at $3.50 per person Per Person Cost Food $19.99 Monk’s Traditional Package Monk’s Seasonal Salad Mixed field greens with seasonal additions of vegetables and cheese, with our balsamic vinaigrette Choice of three traditional meats Choice of any three side dishes* Choice of Custard Filled Cornbread or Slider Buns Always includes Bread n' Butter pickles and up to three Monk’s BBQ sauce choices *Add additional sides at $3.50 per person Monk’s Traditional Meats and Offerings Beef Brisket (smoked) Braised Chicken Thighs Dry Rub Chicken Leg Quarters (smoked) Maple Glazed Pork Loin (grilled) Pulled Chicken (brined and smoked) Pulled Pork Shoulder (smoked) Per Person Cost Food $23.99 Monk’s Premium Package Monk’s Seasonal Salad Mixed field greens with seasonal additions of vegetables and cheese, with our balsamic vinaigrette Choice of three premium meats or premium meats with combination of traditional offerings Choice of any three side dishes* Choice of Custard Filled Cornbread -

Click to Download

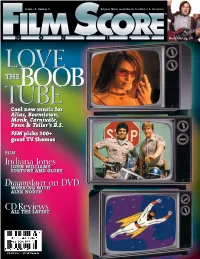

Volume 8, Number 8 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Rock On! pg. 10 LOVE thEBOOB TUBE Cool new music for Alias, Boomtown, Monk, Carnivàle, Penn & Teller’s B.S. FSM picks 100+ great great TTV themes plus Indiana Jones JO JOhN WIllIAMs’’ FOR FORtuNE an and GlORY Dragonslayer on DVD WORKING WORKING WIth A AlEX NORth CD Reviews A ALL THE L LAtEST $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada CONTENTS SEPTEMBER 2003 DEPARTMENTS COVER STORY 2 Editorial 20 We Love the Boob Tube The Man From F.S.M. Video store geeks shouldn’t have all the fun; that’s why we decided to gather the staff picks for our by-no- 4 News means-complete list of favorite TV themes. Music Swappers, the By the FSM staff Emmys and more. 5 Record Label 24 Still Kicking Round-up Think there’s no more good music being written for tele- What’s on the way. vision? Think again. We talk to five composers who are 5 Now Playing taking on tough deadlines and tight budgets, and still The Man in the hat. Movies and CDs in coming up with interesting scores. 12 release. By Jeff Bond 7 Upcoming Film Assignments 24 Alias Who’s writing what 25 Penn & Teller’s Bullshit! for whom. 8 The Shopping List 27 Malcolm in the Middle Recent releases worth a second look. 28 Carnivale & Monk 8 Pukas 29 Boomtown The Appleseed Saga, Part 1. FEATURES 9 Mail Bag The Last Bond 12 Fortune and Glory Letter Ever. The man in the hat is back—the Indiana Jones trilogy has been issued on DVD! To commemorate this event, we’re 24 The girl in the blue dress.