Transforming Thinking Through Cybernetic Epistemology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

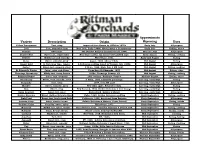

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

The Anthroposophic Art of Ernesto Genoni, Goetheanum, 1924

The Anthroposophic Art of Ernesto Genoni, Goetheanum, 1924 John Paull The images 1-16 were first exhibited at the exhibition, Angels of the First Class: The Anthroposophic Art of Ernesto Genoni, Goetheanum, 1924 held at: VITAL YEARS CONFERENCE 2016 – CRADLE OF A HEALTHY LIFE Date: Jul 5 2016 - Jul 9 2016 Venue: Tarremah Steiner School, Hobart, Tasmania Cover image: Image 1. Angels of the Cradle “In painting, too, Dr Steiner showed the way to a new ideal. He trained his pupils to experience the inner life of colour - out of the language of colours themselves - to give birth to form, without ever drawing in the forms beforehand. This was a difficult ideal to fulfil and it required the development of a new technique. But in the course of years a considerable number of artists, each in his individual way, have produced beautiful works in this direction Looking at some of these pictures, whether of human forms and groups, or sceneries of Nature, or more purely spiritual Imaginations, one experiences a kind of liberation; one feels one never realised before what the pure world of colour can convey. It is as though a new world were being opened” George Adams Kaufmann, 1933, p.46. Journal of Organics INTERNATIONAL, OPEN ACCESS, PEER REVIEWED, FREE A Special Issue devoted to an account of the Anthroposophic art of Ernesto Genoni, Australia’s pioneer of biodynamic and organic farming. Volume 3 Number 2, September 2016 jOrganics.org ISSN 2204-1060 eISSN 2204-1532 !2 Journal of Organics 3(2) 2016 !2 The Anthroposophic Art of Ernesto Genoni, Goetheanum, 1924 John Paull School of Land & Food, University of Tasmania [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Ernesto Genoni (1885-1975) was a pioneer of biodynamic and organic farming in Australia. -

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

Waldorf Education & Anthroposophy 2

WALDORF EDUCATION AND ANTHROPOSOPHY 2 [XIV] FOU NDAT IONS OF WALDORF EDUCAT ION R U D O L F S T E I N E R Waldorf Education and Anthroposophy 2 Twelve Public Lectures NOVEMBER 19,1922 – AUGUST 30,1924 Anthroposophic Press The publisher wishes to acknowledge the inspiration and support of Connie and Robert Dulaney ❖ ❖ ❖ Introduction © René Querido 1996 Text © Anthroposophic Press 1996 The first two lectures of this edition are translated by Nancy Parsons Whittaker and Robert F. Lathe from Geistige Zusammenhänge in der Gestaltung des Menschlichen Organismus, vol. 218 of the Complete Works of Rudolf Steiner, published by Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach, Switzerland, 1976. The ten remaining lectures are a translation by Roland Everett of Anthroposophische Menschenkunde und Pädagogik, vol. 304a of the Complete Works of Rudolf Steiner, published by Rudolf Steiner Verlag, Dornach, Switzerland, 1979. Published by Anthroposophic Press RR 4, Box 94 A-1, Hudson, N.Y. 12534 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Steiner, Rudolf, 1861–1925. [Anthroposophische Menschenkunde und Pädagogik. English] Waldorf education and anthroposophy 2 : twelve public lectures. November 19, 1922–August 30, 1924 / Rudolf Steiner. p. cm. — (Foundations of Waldorf education ;14) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-88010-388-4 (pbk.) 1. Waldorf method of education. 2. Anthroposophy. I. Title. II. Series. LB1029.W34S7213 1996 96-2364 371.3'9— dc20 CIP 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and articles. -

Academic and Social Effects of Waldorf Education on Elementary School Students

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 5-2018 Academic and Social Effects of Waldorf Education on Elementary School Students Christian Zepeda California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Early Childhood Education Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Educational Psychology Commons, Elementary Education Commons, Elementary Education and Teaching Commons, International and Comparative Education Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, and the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Zepeda, Christian, "Academic and Social Effects of Waldorf Education on Elementary School Students" (2018). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 272. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all/272 This Capstone Project (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects and Master's Theses at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: EFFECTS OF WALDORF EDUCATION 1 Academic and Social Effects of Waldorf Education on Elementary School Students Christian Zepeda Liberal Studies Department College of Education California State University Monterey Bay EFFECTS OF WALDORF EDUCATION 2 Abstract As society becomes more critical of public education, alternative education systems are becoming more popular. The Waldorf education system, based on the philosophy of Rudolf Steiner, has increased in popularity and commonality each decade. Currently, 23 Waldorf institutions exist in California. -

Ms. Tomer Rosen-Grace Harduf 1793000, D.N. Hamovil [email protected] Last Update: October 2016

Ms. Tomer Rosen-Grace Harduf 1793000, D.N. Hamovil [email protected] Last Update: October 2016 Tomer Rosen Grace, Translator, Copy editor & Proofreader CV, Anthroposophical and other Translation Projects, and relevant work experience Name: Tomer Yasmin Rosen Grace Born: 12 September 1968, Mother of 2. Currently living in Harduf Anthroposophic Community in the North of Israel. Over the past 25 years I have translated 15 books as well as articles from English and German into Hebrew, mostly in the areas of literature, Jewish and New Age spirituality, Anthroposophy, self help, parenting, couples help and new age psychology & channelling. Recently I also translated an 300-page autobiography from Hebrew into English. I have also written, illustrated and self-published 12 children's books in Hebrew to-date, with more intended in near future. The first of them I also translated into English and published on Amazon July 2015. Part of my expertise lies in presenting a well written translated text, i.e. I always edit my own text for accuracy and style, making sure each dot lies in its rightful place. In addition to translating, I also take editing and proof-reading works in Hebrew, concentrating on polishing-up the text in terms of style and spelling/punctuation, rather than re-writing it. Punctuation in Hebrew (Nikkud) is another skill I offer, as well as editing already-translated work from German or English, including comparing the translation to the original and correcting it as necessary. Translations and Editing of Anthroposophical Writings -

Table of Contents Introduction

Young School’s Guide 2018 Table of Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 How to Use this Guide...................................................................................................................................... 2 Establishing a Community .............................................................................................................................. 3 AWSNA Principles for Waldorf Schools ........................................................................................................ 4 AWSNA Policies & Practices ............................................................................................................................. 6 Establishing a Healthy School in Light of AWSNA Principles ................................................................ 9 Independence and Self Reflection ................................................................................................................. 9 Articulated Decision-Making ......................................................................................................................... 9 Support for Faculty & Staff............................................................................................................................. 9 Articulated Educational Program ............................................................................................................... 10 Support -

Anthroposophy Is a Source of Spiritual Knowledge and a Practice of Inner Development. Through It One Seeks to Penetrate The

Anthroposophy is a source of spiritual knowledge and a practice of inner development. Through it one seeks to penetrate the mystery of our relationship with the spiritual world by searching for answers and insights that come through a schooling of one’s inner life. It draws, and strives to build on, the spiritual research of Rudolf Steiner, who maintained that every human being (Anthropos) has the inherent wisdom (Sophia) to solve the riddles of existence and to transform both self and society. Anthroposophy is a human oriented spiritual philosophy that reflects and speaks to the basic deep spiritual questions of humanity, to our basic artistic needs, to the need to relate to the world out of a scientific attitude of mind, and to the need to develop a relation to the world in complete freedom. It is a path of knowledge or spiritual research, developed on the basis of European idealistic philosophy, rooted in the philosophies of Aristotle, Plato, and Thomas Aquinas. It is primarily defined by its method of research, and secondly by the possible knowledge or experiences this leads to. From this perspective, anthroposophy can also be called spiritual science. As such, it is an effort to develop not only natural scientific, but also a spiritual scientific research on the basis of the idealistic tradition, in the spirit of the historical strivings, that have led to the development of modern science. On this basis, anthroposophy strives to bridge the clefts that have developed since the Middle Ages between the sciences, the arts and the spiritual strivings of humanity as the three main areas of human culture, and build the foundation for a synthesis of them for the future. -

Survey of Apple Clones in the United States

Historic, archived document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. 5 ARS 34-37-1 May 1963 A Survey of Apple Clones in the United States u. S. DFPT. OF AGRffini r U>2 4 L964 Agricultural Research Service U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE PREFACE This publication reports on surveys of the deciduous fruit and nut clones being maintained at the Federal and State experiment stations in the United States. It will b- published in three c parts: I. Apples, II. Stone Fruit. , UI, Pears, Nuts, and Other Fruits. This survey was conducted at the request of the National Coor- dinating Committee on New Crops. Its purpose is to obtain an indication of the volume of material that would be involved in establishing clonal germ plasm repositories for the use of fruit breeders throughout the country. ACKNOWLEDGMENT Gratitude is expressed for the assistance of H. F. Winters of the New Crops Research Branch, Crops Research Division, Agricultural Research Service, under whose direction the questionnaire was designed and initial distribution made. The author also acknowledges the work of D. D. Dolan, W. R. Langford, W. H. Skrdla, and L. A. Mullen, coordinators of the New Crops Regional Cooperative Program, through whom the data used in this survey were obtained from the State experiment stations. Finally, it is recognized that much extracurricular work was expended by the various experiment stations in completing the questionnaires. : CONTENTS Introduction 1 Germany 298 Key to reporting stations. „ . 4 Soviet Union . 302 Abbreviations used in descriptions .... 6 Sweden . 303 Sports United States selections 304 Baldwin. -

Systematically Integrating DNA Information Into Breeding: the MAB

Systematically integrating DNA information into breeding: The MAB Pipeline, case studies in apple and cherry Amy Iezzoni January 31, 2013 Cornell MSU Susan Brown Amy Iezzoni (PD) Kenong Xu Jim Hancock Dechun Wang Clemson Cholani Weebadde Ksenija Gasic Gregory Reighard Univ. of Arkansas John Clark WSU Texas A&M USDA-ARS Dave Byrne Cameron Peace Nahla Bassil Dorrie Main Univ. of Minnesota Gennaro Fazio Univ. of CA-Davis Kate Evans Chad Finn Karina Gallardo Jim Luby Tom Gradziel Vicki McCracken Chengyan Yue Plant Research Intl, Carlos Crisosto Nnadozie Oraguzie Netherlands Oregon State Univ. Eric van de Weg Univ. of New Hamp. Alexandra Stone Marco Bink Tom Davis Outline of Presentation The MAB Pipeline Apple skin color Cherry flesh color The MAB Pipeline “Jewels in the Genome” - discovering, polishing, applying QTL discovery MAB Pipelining Breeding (looks promising...) (polishing...) (assembling into masterpieces) Socio-Economics Surveys (example for apple) Washington Michigan Market Breeders Producers Producers Intermediaries Fruit flavor 43 41 23 Fruit crispness 15 23 10 Exterior color 26 Fruit firmness 6 7 5 Shelf life at retail 7 7 3 Sweetness/soluble solids 6 7 3 Sugar/acid balance 9 7 External appearance 13 No storage disorders 7 4 Disease resistance 2 5 Storage life 5 Other fruit quality…2 3 Size 3 Juiciness 2 Tartness Shape Phytonutrient Aroma % of respondents020406080100 Reference Germplasm McIntosh Melba LivelRasp Jolana Williams F_Spartan Spartan PRI14-126 Starr OR38T610 F_Williams NJ53 PRI14-226 Minnesota Delicious KidsOrRed -

Handling of Apple Transport Techniques and Efficiency Vibration, Damage and Bruising Texture, Firmness and Quality

Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences PUBLISHED BY: B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ACTIVITIES OF WP9 IN THE CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE AGROPHYSICS CONTRACT NO: QLAM-2001-00428 CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE FOR APPLIED PHYSICS IN SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE WITH THE th ACRONYM AGROPHYSICS IS FOUNDED UNDER 5 EU FRAMEWORK FOR RESEARCH, TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT AND DEMONSTRATION ACTIVITIES GENERAL SUPERVISOR OF THE CENTRE: PROF. DR. RYSZARD T. WALCZAK, MEMBER OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES PROJECT COORDINATOR: DR. ENG. ANDRZEJ STĘPNIEWSKI WP9: PHYSICAL METHODS OF EVALUATION OF FRUIT AND VEGETABLE QUALITY LEADER OF WP9: PROF. DR. ENG. BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI, JR. REVIEWED BY PROF. DR. ENG. JÓZEF KOWALCZUK TRANSLATED (EXCEPT CHAPTERS: 1, 2, 6-9) BY M.SC. TOMASZ BYLICA THE RESULTS OF STUDY PRESENTED IN THE MONOGRAPH ARE SUPPORTED BY: THE STATE COMMITTEE FOR SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH UNDER GRANT NO. 5 P06F 012 19 AND ORDERED PROJECT NO. PBZ-51-02 RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF POMOLOGY AND FLORICULTURE B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ©Copyright by BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES LUBLIN 2006 ISBN 83-89969-55-6 ST 1 EDITION - ISBN 83-89969-55-6 (IN ENGLISH) 180 COPIES, PRINTED SHEETS (16.8) PRINTED ON ACID-FREE PAPER IN POLAND BY: ALF-GRAF, UL. -

Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin, Architects of Anthroposophy

Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin, Architects of Anthroposophy Dr John Paull [email protected] A century ago, on the 23rd of May 1912, the winning design of Canberra was announced. Soon after, two talented Chicago architects set sail for Australia. Their plan for Australia’s national capital, already named Canberra but at the time merely an empty paddock, had won first prize in an international competition which attracted 137 entries. The winning prize money for the design was a modest £1750 (McGregor, 2009). Walter Burley Griffin (1876-1937) and Marion Mahony (1871-1961) were married in the year preceding the win. Marion had nagged Walter to enter the competition, “What’s the use of thinking about a thing like this for ten years if when the time comes you don’t get it done in time!” She pointed out the practicalities: “Perhaps you can design a city in two days but the drawings take time and that falls on me” (Griffin, 1949, volume IV p.294). After the win was announced, Walter declared: “I have planned it not in a way that I expected any government in the world would accept. I have planned an ideal city - a city that meets my ideal of a city of the future” (New York Times, 1912). Marion chronicled events of their life together in a typewritten four- volume memoir of over 1600 pages (Griffin, 1949). Her memoir documents their life together and liberally reproduces personal correspondence between them and their associates. Her unpublished manuscript reveals the intensity with which she and Walter embraced the thoughts of Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) and anthroposophy.