The Effects of Performance Appraisal on Staff Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

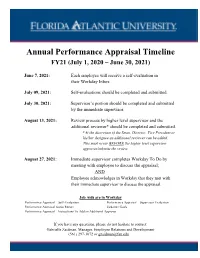

Performance Appraisal Timeline And

Annual Performance Appraisal Timeline FY21 (July 1, 2020 – June 30, 2021) June 7, 2021: Each employee will receive a self-evaluation in their Workday Inbox July 09, 2021: Self-evaluations should be completed and submitted. July 30, 2021: Supervisor’s portion should be completed and submitted by the immediate supervisor. August 13, 2021: Review process by higher level supervisor and the additional reviewer* should be completed and submitted. *At the discretion of the Dean, Director, Vice President or his/her designee an additional reviewer can be added. This must occur BEFORE the higher level supervisor approves/submits the review. August 27, 2021: Immediate supervisor completes Workday To Do by meeting with employee to discuss the appraisal; AND Employee acknowledges in Workday that they met with their immediate supervisor to discuss the appraisal. Job Aids are in Workday Performance Appraisal – Self-Evaluation Performance Appraisal – Supervisor Evaluation Performance Appraisal Status Report Updating Goals Performance Appraisal – Instructions To Add an Additional Approver If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact: Gabrielle Zaidman, Manager, Employee Relations and Development (561) 297-3072 or [email protected] Annual Performance Appraisal Process FY21 (July 1, 2020 – June 30, 2021) We are excited to kick off the performance appraisal process for all AMP and SP employees, for work completed in FY21 (July 1, 2020 - June 30, 2021). Please note that all work completed after July 1, 2021, should be included in the performance appraisal for next year, FY22. The following are the steps to complete the performance appraisal process. Note that all notifications will appear in your WD Inbox: Each employee will receive a self-evaluation in their WD Inbox on June 7, 2021. -

City Employee Handbook 2020

Table of Contents INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT ................................................................................................................ 7 EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY POLICY ...................................................................................... 8 CODE OF ETHICS / CONFLICTS OF INTEREST ......................................................................................... 9 ROMANTIC AND/OR SEXUAL RELATIONSHIP WITH OTHER EMPLOYEES ............................................ 10 DOING BUSINESS WITH OTHER EMPLOYEES ....................................................................................... 10 OUTSTANDING WARRANT POLICY ...................................................................................................... 10 REPORTING ARRESTS .......................................................................................................................... 11 IMMIGRATION LAW COMPLIANCE ..................................................................................................... 11 JOB DESCRIPTIONS .............................................................................................................................. 12 DISABILITY ACCOMMODATION (ADA REQUESTS) ............................................................................... 16 Definition of reasonable accommodation ...................................................................................... 16 Examples of reasonable accommodation ...................................................................................... -

5—Government Organization and Employees § 4302

Page 343 TITLE 5—GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATION AND EMPLOYEES § 4302 HISTORICAL AND REVISION NOTES—CONTINUED Par. (2)(E). Pub. L. 95–251 substituted ‘‘administrative law judge’’ for ‘‘hearing examiner’’. Revised Statutes and 1970—Par. (1)(ii). Pub. L. 91–375 repealed cl. (ii) which Derivation U.S. Code Statutes at Large excluded postal field service from definition of ‘‘agen- June 17, 1957, Pub. L. 85–56, cy’’. § 2201(21), 71 Stat. 159. July 11, 1957, Pub. L. 85–101, CHANGE OF NAME 71 Stat. 293. ‘‘Government Publishing Office’’ substituted for Sept. 2, 1958, Pub. L. 85–857, ‘‘Government Printing Office’’ in par. (1)(B) on author- § 13(p), 72 Stat. 1266. Mar. 26, 1964, Pub. L. 88–290, ity of section 1301(b) of Pub. L. 113–235, set out as a note ‘‘Sec. 306(b)’’, 78 Stat. 170. preceding section 301 of Title 44, Public Printing and Documents. In paragraph (1), the term ‘‘Executive agency’’ is sub- EFFECTIVE DATE OF 1996 AMENDMENT stituted for the reference to ‘‘executive departments, the independent establishments and agencies in the ex- Amendment by Pub. L. 104–201 effective Oct. 1, 1996, ecutive branch, including corporations wholly owned see section 1124 of Pub. L. 104–201, set out as a note by the United States’’ and ‘‘the General Accounting Of- under section 193 of Title 10, Armed Forces. fice’’. The exception of ‘‘a Government controlled cor- EFFECTIVE DATE OF 1978 AMENDMENT poration’’ is added in subparagraph (vii) to preserve the application of this chapter to ‘‘corporations wholly Amendment by Pub. L. 95–454 effective 90 days after owned by the United States’’. -

Workplace Bullying; 3

Sticks, stones and intimidation: How to manage bullying and promote resilience Ellen Fink-Samnick Charlotte Sortedahl Principal Associate Professor, Univ. of Wis. Eau Claire EFS Supervision Strategies, LLC Chair, CCMC Board of Commissioners Proprietary to CCMC® 1 Agenda • Welcome and Introductions • Learning Outcomes • Presentation: • Charlotte Sortedahl, DNP, MPH, MS, RN, CCM Chair, CCMC Board of Commissioners • Ellen Fink-Samnick, MSW, ACSW, LCSW, CCM, CRP Principal, EFS Strategies, LLC • Question and Answer Session 2 Audience Notes • There is no call-in number for today’s event. Audio is by streaming only. Please use your computer speakers, or you may prefer to use headphones. There is a troubleshooting guide in the tab to the left of your screen. Please refresh your screen if slides don’t appear to advance. 3 How to submit a question To submit a question, click on Ask Question to display the Ask Question box. Type your question in the Ask Question box and submit. We will answer as many questions as time permits. 4 Audience Notes • A recording of today’s session will be posted within one week to the Commission’s website, www.ccmcertification.org • One continuing education credit is available for today’s webinar only to those who registered in advance and are participating today. 5 Learning Outcomes Overview After the webinar, participants will be able to: 1. Define common types of bullying across the health care workplace; 2. Explore the incidence and scope of workplace bullying; 3. Discuss the implications for case management practice; and 4. Provide strategies to manage bullying and empower workplace resilience. -

Whistleblower Protections for Federal Employees

Whistleblower Protections for Federal Employees A Report to the President and the Congress of the United States by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board September 2010 THE CHAIRMAN U.S. MERIT SYSTEMS PROTECTION BOARD 1615 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20419-0001 September 2010 The President President of the Senate Speaker of the House of Representatives Dear Sirs and Madam: In accordance with the requirements of 5 U.S.C. § 1204(a)(3), it is my honor to submit this U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board report, Whistleblower Protections for Federal Employees. The purpose of this report is to describe the requirements for a Federal employee’s disclosure of wrongdoing to be legally protected as whistleblowing under current statutes and case law. To qualify as a protected whistleblower, a Federal employee or applicant for employment must disclose: a violation of any law, rule, or regulation; gross mismanagement; a gross waste of funds; an abuse of authority; or a substantial and specific danger to public health or safety. However, this disclosure alone is not enough to obtain protection under the law. The individual also must: avoid using normal channels if the disclosure is in the course of the employee’s duties; make the report to someone other than the wrongdoer; and suffer a personnel action, the agency’s failure to take a personnel action, or the threat to take or not take a personnel action. Lastly, the employee must seek redress through the proper channels before filing an appeal with the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (“MSPB”). A potential whistleblower’s failure to meet even one of these criteria will deprive the MSPB of jurisdiction, and render us unable to provide any redress in the absence of a different (non-whistleblowing) appeal right. -

Performance Appraisal and Terminations: a Review of Court Decisions Since Brito V

PERSONNEL PSYCHOLOGY 1987. 40 PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL AND TERMINATIONS: A REVIEW OF COURT DECISIONS SINCE BRITO V. ZIA WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR PERSONNEL PRACTICES GERALD V. BARRETT The University of Akron MARY C. KERNAN Kent State University Court cases since the classic Brito v. Zia (1973) decision dealing with terminations based on subjective performance appraisals are reviewed. Professional interpretations of Brito v. Zia are aJso examined and crit- icized in light of professional practice and subsequent court decisions. Major themes and issues are distilled from the review of cases, and im- plications and recommendations for personnel practices were discussed. Legal issues pertaining to personnel decisions have received a great deal of attention in recent years (Cascio & Bemardin, 1981; Faley, Kleiman & Lengnick-Hall, 1984; Feild & HoUey, 1982; HoUey & Feild, 1975; Kleiman & Durham, 1981). As a result of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, any personnel practice that adversely affects certain classes of individuals is deemed unlawful unless justified by business necessity. The termination of an employee is probably the most critical personnel decision an organiza- tion can make. The United States is unique among industrialized countries in that terminations, or firings, are quite commonplace. While there are no accurate figures, approximately three million people are fired each year in the private sector (Stieber, 1984). Schreiber (1983) has estimated that 200,000 of these employees are fired "imfairly." In addition to Title VII, other statutes have been enacted to protect em- ployees against unjust termination and discrimination (Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967; National Labor Relations Act of 1935). In countering a charge of discrimination, the organization invariably claims that an alleged unfair termination resulted solely from poor job perfor- mance. -

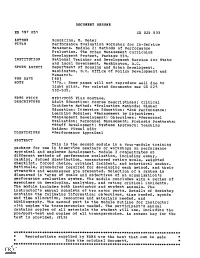

Performance Evaluation Workshop for In-Service Managers. Module 2: Methods of Performance Evaluation

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 197 051 CE 025 533 AUTHOR Scontrino, M. Peter TITLE Performance Evaluation Workshop for In-Service Managers. Module 2: Methods of Performance Evaluation. The Urban Management Curriculum Development Protect, Package XIV. INSTITUTION National Training and Development Service for State and Local Government, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Department of Housing and Urban Development, Washington, D.C. Office of Policy Development and Research. PUB DATE (BO) NOTE 117p.: Some pages will not reproduce well due to light print. For related documents see CE 025 532-535. !DRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Education: Course Descriptions: Critical Incidents Method: *Evaluation Methods: Higher Education: Inservice Education: *Job Performance: Learning Modules: *Management by Objectives: *Management Development: Objectives: *Personnel Evaluation: Personnel Management; Pretests Posttests: *Staff Development: Systems Approach: Teaching Guides: Visual Aids IDENTIFIERS *Performance Appraisal ABSTRACT This is the second module in a four-module training package for use in inservice seminars or workshops on performance appraisal and employee development. Module 2 concentrates on different methods of performance evaluation, including essay, ranking, forced distribution, nonanchored rating scale, weighted checklist, forced choice, critical incident, and behavioral anchor. Rationale, procedures required for developing each method, and their strengths and veaknesses are presented. Selection of a system is discussed in terms of goals and objectives of an organization's performance evaluation system. The module concludes with a series of exercises on developing, analysing, and rating critical incidents. The module includes both instructor and student manuals. The instructor's manual consists of two major parts. Details of Workshop contains the following information: objectives, time needed, agenda and time allocation, resources and materials needed, and bibliography. -

Prognosis of Workplace Bullying in Selected Health Care Organizations in the Philippines

Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2017, 5, 154-174 http://www.scirp.org/journal/jss ISSN Online: 2327-5960 ISSN Print: 2327-5952 Prognosis of Workplace Bullying in Selected Health Care Organizations in the Philippines Gloria M. Alcantara1, Eric G. Claudio2, Arneil G. Gabriel3* 1Guidance Coordinator, College of Information and Communications Technology, Cabanatuan City, Philippines 2International Linkages Office, Cabanatuan City, Philippines 3Head Graduate School Research Department, Nueva Ecija University of Science and Technology, Cabanatuan City, Philippines How to cite this paper: Alcantara, G.M., Abstract Claudio, E.G. and Gabriel, A.G. (2017) Prognosis of Workplace Bullying in Selected The major objective of the paper is to determine the existence of workplace Health Care Organizations in the Philip- bullying in selected health care organizations in the Philippines. The approach pines. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 5, used in the study is a mixture of qualitative and quantitative research me- 154-174. thods. The findings show that a median range of score on six factors to https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2017.59012 workplace bullying was established. Results also found that: no significant re- Received: August 7, 2017 lationship exists between demographic profile of participants and their diag- Accepted: September 15, 2017 nosis of workplace bullying. The statistical treatment of t-test proved that Published: September 18, 2017 there is no significant difference between the mean scores of the two groups as shown by a t-value of 2.02 in a two tailed test. The overall bullying prevalence Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. scale is moderate as determined by individual responses of the participants. -

Managing Teacher Appraisal and Performance

Managing Teacher Appraisal and Performance This book deals with the biggest single issue currently facing school managers, how they should appraise the performance of their staff and the implications of this process. Recent government initiatives have brought this matter to the fore and headteachers are now required by law to implement appraisal. This book brings together the latest thinking on the subject and places it directly in the context of school management. Managing Teacher Appraisal and Performance examines the ways in which various countries have tackled the issue, ranging from the ‘hire and fire’ approach, to concentrating on professional development. The book includes sections on school leadership, the professional development of teachers and the implications for the future of teacher appraisal and performance. The chapters are written by distinguished international academics, writers and researchers, who report and analyse the significance of their work in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa, Singapore and the USA. This timely and authoritative book is essential reading for headteachers and school managers seeking guidance on the appraisal process. David Middlewood is Director of School-based Programmes at the University of Leicester’s Educational Management Development Unit. Carol Cardno is Professor of Educational Management and Head of the School of Education at UNITEC Institute of Technology, New Zealand. Managing Teacher Appraisal and Performance A Comparative Approach Edited by David Middlewood and Carol Cardno London and New York First published 2001 by RoutledgeFalmer 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by RoutledgeFalmer 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. -

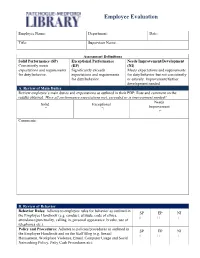

Employee Evaluation

Employee Evaluation Employee Name: Department: Date: Title: Supervisor Name: Assessment Definitions Solid Performance (SP) Exceptional Performance Needs Improvement/Development Consistently meets (EP) (NI) expectations and requirements Significantly exceeds Meets expectations and requirements for duty/behavior. expectations and requirements for duty/behavior but not consistently for duty/behavior. or entirely. Improvement/further development needed. A. Review of Main Duties Review employee’s main duties and expectations as outlined in their PDP. Rate and comment on the results obtained. Were all performance expectations met, exceeded or is improvement needed? Needs Solid Exceptional Improvement Comments: B. Review of Behavior Behavior Rules: Adheres to employee rules for behavior as outlined in SP EP NI the Employee Handbook (e.g. conduct, attitude, code of ethics, attendance/punctuality, calling in, personal appearance, breaks, use of telephones etc.). Policy and Procedures: Adheres to policies/procedures as outlined in SP EP NI the Employee Handbook and on the Staff Blog (e.g. Sexual Harassment, Workplace Violence, Email, Computer Usage and Social Networking Policy, Petty Cash Procedures etc). Teamwork/Cooperation: Establishes and maintains positive, productive relationships with coworkers. Assists/collaborates with SP EP NI others as required ensuring an efficient and effective work environment Addresses and resolves conflicts without assistance. Treats people fairly and respectfully regardless of culture, gender, race or position. Customer Service: Demonstrates a personal commitment to public service. Builds and maintains customer satisfaction. Maintains good SP EP NI customer service skills (knowledgeable of services, open, approachable manner, positive tone, listens, etc.). Respects confidentiality and refrains from gossiping and discussing customers on the public floor. Diffuses difficult customers/situations. -

Formal Performance Appraisal Review Checklist for Managers in Advance of the Formal Review Meeting: Set up the Meeting: � Set a Date for the Evaluation

Formal Performance Appraisal Review Checklist for Managers In advance of the formal review meeting: Set up the Meeting: Set a date for the evaluation. Ask employee to complete a self-evaluation (optional). Forward a copy of the organization’s mission, vision, guiding values and goals in advance. Schedule enough time for the meeting (usually one hour). Notified the employee of the meeting and logistics, preferably not in your office. Prepare for the meeting: Review employee’s self-evaluation (optional) and job description. Review employee’s previous year’s goals. Review employee’s performance record (See Performance Observations). Create draft performance review in the online system. Draft goals to be discussed in the online system. Prepare a list of expectations to discuss. Review organizational objectives. Share draft appraisal with your manager for input (optional). Refresh memory about the employee including: Length of service with the department/University. Educational background. Experience background. Level of technical skills. Current projects. Projects the employee has completed during the review period. Attendance records. The day of the performance review: Arranged for all calls, visitors, and interruptions to be avoided. Make the room comfortable, seating, lighting, and air temperature, etc. Employee job description. Draft performance review. List of goals and objectives created during the last review. Performance documentation. List of expectations to be discussed. Draft goals for next year. Paper and pen for taking notes. During the Evaluation Provide employee with a listing of your expectations for their position. Discuss employee’s progress toward goals and assessment of competencies. Identify work related goals. Ask employee about undocumented contributions to the unit. -

Performance Management and Appraisal

8 Performance Management and Appraisal Learning Outcomes After studying this chapter you should be able to: 8.1 Discuss the difference between performance management and performance appraisal 8.2 Identify the necessary characteristics of accurate performance management tools 8.3 List and briefly discuss the purposes for performance appraisals 8.4 Identify and briefly discuss the options for “what” is evaluated in a performance appraisal 8.5 Briefly discuss the commonly used performance measurement methods and forms 8.6 Identify and briefly discuss available options for the rater/evaluator 8.7 Briefly discuss the value and the drawbacks of a 360° evaluation 8.8 Identify some of the common problems with the performance appraisal process 8.9 Identify the major steps we can take to avoid problems with the appraisal process 8.10 Briefly discuss the differences between evaluative performance reviews and developmental performance reviews 8.11 Define the following terms: Performance management Graphic rating scale form Performance appraisal Behaviorally Anchored Motivation Rating Scale (BARS) Traits form Behaviors Ranking method Results 360° evaluation Critical incidents method Bias Management by Objectives Stereotyping (MBO) method Electronic Performance Narrative method or form Monitoring (EPM) Chapter 8 Outline Performance Management Systems Who Should Assess Performance? Performance Management Versus Performance Appraisal Supervisor The Performance Appraisal Process Peers Accurate Performance Measures Subordinates Why Do We Conduct Performance