The Importance of Valid Selection and Performance Appraisal Do Management Practices Figure in Case Law? Stan Malos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of the Puget Sound Telecommuting Demonstration

Evaluation of the Puget Sound Telecommuting Demonstration Dee Christensen, Michael Farley, Maureen Quaid and laurel Heifetz Washington State Energy Office Introduction Program Implementation The transportation sector accounts for 28 percent of all Twenty-five organizations and about 250 telecommuters, energy consumption in the United States and is a major their co-workers, and supervisors are involved in the contributor to the nation's air pollution problems (U.S. Demonstration. WSEO conducted an extensive recruitment Department of Energy May 1991. State Energy Data of organizations representing a cross section of the Paget Report). Recent improvements in automotive fuel effi Sound economy. Each organization received assistance in ciency have been overwhelmed by increases in vehicle developing telecommuting policies and procedures, select miles travelled. According to the Federal Highway ing telecommuters, and training their telecommuters and Administration, between 1960 and 1980 traffic volumes their supervisors. almost doubled, while the population grew by 26 percent. Also, traffic congestion is expected to increase by Recruitment 400 percent over the next 20 years on the interstate freeway system and over 200 percent on surface roads. Initial recruitment of potential participating organizations for the Demonstration began with the June 1989 In order to reduce energy consumption and air pollution in "Governor's Conference on Telecommuting: An Alternate the transportation sector, vehicle use and traffic congestion Route To Work.· At the conference, organization repre must be decreased. Transportation demand management sentatives were surveyed to determine their level of (TDM) strategies attempt to accomplish this by promoting interest in pursuing the telecommuting option within their alternatives to single-occupant vehicles such as transit, organization. -

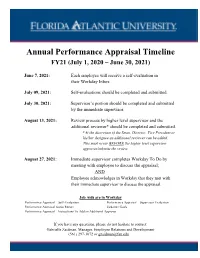

Performance Appraisal Timeline And

Annual Performance Appraisal Timeline FY21 (July 1, 2020 – June 30, 2021) June 7, 2021: Each employee will receive a self-evaluation in their Workday Inbox July 09, 2021: Self-evaluations should be completed and submitted. July 30, 2021: Supervisor’s portion should be completed and submitted by the immediate supervisor. August 13, 2021: Review process by higher level supervisor and the additional reviewer* should be completed and submitted. *At the discretion of the Dean, Director, Vice President or his/her designee an additional reviewer can be added. This must occur BEFORE the higher level supervisor approves/submits the review. August 27, 2021: Immediate supervisor completes Workday To Do by meeting with employee to discuss the appraisal; AND Employee acknowledges in Workday that they met with their immediate supervisor to discuss the appraisal. Job Aids are in Workday Performance Appraisal – Self-Evaluation Performance Appraisal – Supervisor Evaluation Performance Appraisal Status Report Updating Goals Performance Appraisal – Instructions To Add an Additional Approver If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact: Gabrielle Zaidman, Manager, Employee Relations and Development (561) 297-3072 or [email protected] Annual Performance Appraisal Process FY21 (July 1, 2020 – June 30, 2021) We are excited to kick off the performance appraisal process for all AMP and SP employees, for work completed in FY21 (July 1, 2020 - June 30, 2021). Please note that all work completed after July 1, 2021, should be included in the performance appraisal for next year, FY22. The following are the steps to complete the performance appraisal process. Note that all notifications will appear in your WD Inbox: Each employee will receive a self-evaluation in their WD Inbox on June 7, 2021. -

City Employee Handbook 2020

Table of Contents INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT ................................................................................................................ 7 EQUAL EMPLOYMENT OPPORTUNITY POLICY ...................................................................................... 8 CODE OF ETHICS / CONFLICTS OF INTEREST ......................................................................................... 9 ROMANTIC AND/OR SEXUAL RELATIONSHIP WITH OTHER EMPLOYEES ............................................ 10 DOING BUSINESS WITH OTHER EMPLOYEES ....................................................................................... 10 OUTSTANDING WARRANT POLICY ...................................................................................................... 10 REPORTING ARRESTS .......................................................................................................................... 11 IMMIGRATION LAW COMPLIANCE ..................................................................................................... 11 JOB DESCRIPTIONS .............................................................................................................................. 12 DISABILITY ACCOMMODATION (ADA REQUESTS) ............................................................................... 16 Definition of reasonable accommodation ...................................................................................... 16 Examples of reasonable accommodation ...................................................................................... -

Evaluation of a Program to Reduce Bullying in an Elementary School Jordan Elizabeth Davis Western Kentucky University, J E [email protected]

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 8-2011 Evaluation of a Program to Reduce Bullying in an Elementary School Jordan Elizabeth Davis Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the School Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Jordan Elizabeth, "Evaluation of a Program to Reduce Bullying in an Elementary School" (2011). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1079. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1079 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVALUATION OF A PROGRAM TO REDUCE BULLYING IN AN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Psychology Western Kentucky University Bowling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Specialist in Education By Jordan Elizabeth Davis August 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my committee. I appreciate each committee member’s time and hard work on this project. More specifically, Dr. Jones has been very encouraging and flexible. Without her assistance, my thesis project would not have been possible. I would also like to thank my colleague, Kristin Shiflet. She has kept me on track throughout the course of my school psychology internship. She provided motivation and was responsible for implementing materials from the Bully Free Classroom. Kristin also collected the data and coded all information for confidentiality purposes. Her efforts and dedication to this project is much appreciated. -

New Employee Onboarding Six Month Evaluation Page 1 It Has Been

New Employee Onboarding Six Month Evaluation Page 1 It has been several months since you began employment with the University. You have been presented with information on the University’s culture, mission, vision, values, policies, procedures and benefits. You’ve attended new employee orientation and perhaps other employee development training. Your feedback on your onboarding experience at the University is important to us. Please complete both pages of this evaluation and mail or email it to HR King Bldg/Rm. 222C. Page 1: Please indicate Yes (Y) or No (N) for each statement. Page 2: Answer the questions in the space provided. Use the rating scale to provide your overall opinion of how well the University implemented the new employee onboarding process. Please include your name on the evaluation. How do you feel about your experience? ______I feel eager to begin work. ______I feel welcomed at UNC Charlotte. ______I work in a friendly and supportive environment. ______ I feel engaged and productive in my work. What do you now know about the University and your job? ______I received essential information about the University’s culture, mission, vision and values. ______I received information in a timely manner. ______I know what is expected of me by my supervisor. ______I know what is expected of me by my coworkers. ______I know what my performance expectations are. ______I understand my job responsibilities. ______I understand the purpose of my job. ______I understand how my job fits into the mission of the University. ______I have the essential supplies, equipment, and support to do my job or know where to find them. -

5—Government Organization and Employees § 4302

Page 343 TITLE 5—GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATION AND EMPLOYEES § 4302 HISTORICAL AND REVISION NOTES—CONTINUED Par. (2)(E). Pub. L. 95–251 substituted ‘‘administrative law judge’’ for ‘‘hearing examiner’’. Revised Statutes and 1970—Par. (1)(ii). Pub. L. 91–375 repealed cl. (ii) which Derivation U.S. Code Statutes at Large excluded postal field service from definition of ‘‘agen- June 17, 1957, Pub. L. 85–56, cy’’. § 2201(21), 71 Stat. 159. July 11, 1957, Pub. L. 85–101, CHANGE OF NAME 71 Stat. 293. ‘‘Government Publishing Office’’ substituted for Sept. 2, 1958, Pub. L. 85–857, ‘‘Government Printing Office’’ in par. (1)(B) on author- § 13(p), 72 Stat. 1266. Mar. 26, 1964, Pub. L. 88–290, ity of section 1301(b) of Pub. L. 113–235, set out as a note ‘‘Sec. 306(b)’’, 78 Stat. 170. preceding section 301 of Title 44, Public Printing and Documents. In paragraph (1), the term ‘‘Executive agency’’ is sub- EFFECTIVE DATE OF 1996 AMENDMENT stituted for the reference to ‘‘executive departments, the independent establishments and agencies in the ex- Amendment by Pub. L. 104–201 effective Oct. 1, 1996, ecutive branch, including corporations wholly owned see section 1124 of Pub. L. 104–201, set out as a note by the United States’’ and ‘‘the General Accounting Of- under section 193 of Title 10, Armed Forces. fice’’. The exception of ‘‘a Government controlled cor- EFFECTIVE DATE OF 1978 AMENDMENT poration’’ is added in subparagraph (vii) to preserve the application of this chapter to ‘‘corporations wholly Amendment by Pub. L. 95–454 effective 90 days after owned by the United States’’. -

Job Evaluation – Trends and the Digital Environment

Job Evaluation – Trends and the Digital Environment Why does digitalization have an impact on job evaluation? Job evaluation and grading have been a evaluation and grading in order to develop core HR process over many years, whereby a more flexible approach for agile organiza organizations typically rely on one single tions on the one hand and enable a digital evaluation method. Those methodologies organization and a digital culture on the have not undergone any significant changes other hand. In this context, digitalization and have not been directly impacted by acts as a catalyst for the development of any other major trend. The HR process of job architectures and grading structures as job evaluation and grading often requires a these have to sustain the digital organiza high level of technical expertise and partially tion. Correspondingly, the methods and an ongoing support of resources, depending tools of job evaluation have to also meet on the chosen evaluation method ology. the requirements of digitalization. Job evaluation and grading build the funda mental framework for other HR processes What is driving this trend and what role in the talent lifecycle. does job evaluation play in light of the digital transformation? While this implies no real need for change, we observe an emerging trend in the mar ket to alter traditional approaches to job Job Evaluation – Trends and the Digital Environment Enabling digital transformation digital culture. The concept of “network of through job evaluation teams” has evolved where employees are Larger projects in the area of job evaluation highly networked and collaborate across and grading are typically triggered either by teams and projects, and goals frequently a single event or by multiple factors – both change. -

Workplace Bullying; 3

Sticks, stones and intimidation: How to manage bullying and promote resilience Ellen Fink-Samnick Charlotte Sortedahl Principal Associate Professor, Univ. of Wis. Eau Claire EFS Supervision Strategies, LLC Chair, CCMC Board of Commissioners Proprietary to CCMC® 1 Agenda • Welcome and Introductions • Learning Outcomes • Presentation: • Charlotte Sortedahl, DNP, MPH, MS, RN, CCM Chair, CCMC Board of Commissioners • Ellen Fink-Samnick, MSW, ACSW, LCSW, CCM, CRP Principal, EFS Strategies, LLC • Question and Answer Session 2 Audience Notes • There is no call-in number for today’s event. Audio is by streaming only. Please use your computer speakers, or you may prefer to use headphones. There is a troubleshooting guide in the tab to the left of your screen. Please refresh your screen if slides don’t appear to advance. 3 How to submit a question To submit a question, click on Ask Question to display the Ask Question box. Type your question in the Ask Question box and submit. We will answer as many questions as time permits. 4 Audience Notes • A recording of today’s session will be posted within one week to the Commission’s website, www.ccmcertification.org • One continuing education credit is available for today’s webinar only to those who registered in advance and are participating today. 5 Learning Outcomes Overview After the webinar, participants will be able to: 1. Define common types of bullying across the health care workplace; 2. Explore the incidence and scope of workplace bullying; 3. Discuss the implications for case management practice; and 4. Provide strategies to manage bullying and empower workplace resilience. -

Wendell C. Taylor, Phd, Mph

Taylor 1 WENDELL C. TAYLOR, PHD, MPH CURRENT POSITION AND ADDRESS Associate Professor (with Tenure) of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences Department of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences Center for Health Promotion and Prevention Research The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health 7000 Fannin Street, Suite 2670 Houston, Texas 77030 Telephone: 713.500.9635 Fax: 713.500.9602 E-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Institution Degree Date Conferred Field of Study The University of Texas Health MPH 1989 Community Health Science Center at Houston Practice School of Public Health Houston, TX (Postdoctoral Fellow: 1987–89) Arizona State University PhD 1984 Social Psychology Tempe, AZ Eastern Washington University MS 1974 Psychology Cheney, WA Grinnell College AB 1972 Psychology Grinnell, IA PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 09/2009–Present Admissions Officer Department of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health Houston, TX 09/1999–Present Associate Professor (with Tenure) of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences Department of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences Center for Health Promotion and Prevention Research The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health Houston, TX October 3, 2019 Taylor 2 09/1999–09/2001 Convener of Behavioral Sciences Discipline The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health Houston, TX 09/91–08/99 Assistant Professor -

Whistleblower Protections for Federal Employees

Whistleblower Protections for Federal Employees A Report to the President and the Congress of the United States by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board September 2010 THE CHAIRMAN U.S. MERIT SYSTEMS PROTECTION BOARD 1615 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20419-0001 September 2010 The President President of the Senate Speaker of the House of Representatives Dear Sirs and Madam: In accordance with the requirements of 5 U.S.C. § 1204(a)(3), it is my honor to submit this U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board report, Whistleblower Protections for Federal Employees. The purpose of this report is to describe the requirements for a Federal employee’s disclosure of wrongdoing to be legally protected as whistleblowing under current statutes and case law. To qualify as a protected whistleblower, a Federal employee or applicant for employment must disclose: a violation of any law, rule, or regulation; gross mismanagement; a gross waste of funds; an abuse of authority; or a substantial and specific danger to public health or safety. However, this disclosure alone is not enough to obtain protection under the law. The individual also must: avoid using normal channels if the disclosure is in the course of the employee’s duties; make the report to someone other than the wrongdoer; and suffer a personnel action, the agency’s failure to take a personnel action, or the threat to take or not take a personnel action. Lastly, the employee must seek redress through the proper channels before filing an appeal with the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (“MSPB”). A potential whistleblower’s failure to meet even one of these criteria will deprive the MSPB of jurisdiction, and render us unable to provide any redress in the absence of a different (non-whistleblowing) appeal right. -

Work-Study Evaluation Form

Work-Study Evaluation Form 1: EMPLOYEE INFORMATION Employee Job ID Date Supervisor Job Title Period of Review □ Mid-Fall □ End of Fall □ Mid-Spring □ End of Spring □ Mid-Summer □ End of Summer 2: CORE VALUES Performance Category Rating Comments/Notes/Examples Attendance and Punctuality □ Exceeds expectations Reports for work consistently and on time; Meets expectations provides timely notice of need for absence □ Does not meet expectations or deviations from schedule □ Quality of Work □ Exceeds expectations Work is completed accurately, efficiently, Meets expectations and within deadlines □ □ Does not meet expectations Judgement & Decision-Making □ Exceeds expectations Makes thoughtful, well-reasoned decisions; Meets expectations exercises good judgment; exhibits □ Does not meet expectations resourceful problem-solving □ Initiative & Flexibility □ Exceeds expectations Demonstrates initiative; seeks out additional Meets expectations responsibility; identifies challenges & □ Does not meet expectations solutions; adjusts to unexpected changes □ Communication □ Exceeds expectations Written/verbal communication is clear, Meets expectations organized, & effective; listens and □ Does not meet expectations comprehends well □ Teamwork & Cooperation □ Exceeds expectations Respectful of and works well with Meets expectations colleagues; contributes to group goal □ Does not meet expectations achievement □ 3: LEARNING OUTCOMES Learning Outcome (from Posting) Rating Comments/Notes/Examples □ Needs Improvement □ Adequate □ Displays Mastery □ Needs Improvement -

An Investigation of Middle School Teachers' Perceptions on Bullying Stewart Waters1 & Natalie Mashburn2 Abstract Introduct

Journal of Social Studies Education Research www.jsser.org Sosyal Bilgiler Eğitimi Araştırmaları Dergisi 2017: 8(1), 1-34 An Investigation of Middle School Teachers’ Perceptions on Bullying Stewart Waters1 & Natalie Mashburn2 Abstract The researchers in this study investigated rural middle school teachers’ perspectives regarding bullying. The researchers gathered information about the teachers’ definitions of bullying, where bullying occurs in their school, and how to prevent bullying. Peer-reviewed literature associated with this topic was studied in order to achieve a broader understanding of bullying and to develop a self-administered survey addressing these issues. A total of 21 teachers participated in the survey and the results of this study convey the need to recognize bullying in many forms, appropriately address bullying when it occurs, and incorporate preventive actions that will discourage bullying and encourage acceptance. Keywords: Bullying; Middle School; Teacher Preparation. Introduction Middle school can be a transformative and exciting time for students. However, during these important developmental years, bullying continues to be a persistent and serious issue. In more recent years, national and international concerns relating to the harmful effects of bullying have increased significantly (Thompson & Cohen, 2005). According to Frey and Fisher (2008), bullying has become a part of life for countless students, and can take on many forms within contemporary schools. As a result, bullying has placed a considerable amount of pressure on administrators and teachers to effectively respond to bullying (Bush, 2011). Often, teachers and administrators can be unaware of bullying, making it difficult to develop appropriate policies that are proactive instead of reactive. In 2003, Seals and Young stated that bullying is a persistent and insidious problem that affects roughly one-fourth of the students in the United States.