Interview with Professor Mike Perschon, Macewan University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![The Nemedian Chroniclers #22 [WS16]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7322/the-nemedian-chroniclers-22-ws16-27322.webp)

The Nemedian Chroniclers #22 [WS16]

REHeapa Winter Solstice 2016 By Lee A. Breakiron A WORLDWIDE PHENOMENON Few fiction authors are as a widely published internationally as Robert E. Howard (e.g., in Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Dutch, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Slovak, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, and Yugoslavian). As former REHupan Vern Clark states: Robert E. Howard has long been one of America’s stalwarts of Fantasy Fiction overseas, with extensive translations of his fiction & poetry, and an ever mushrooming distribution via foreign graphic story markets dating back to the original REH paperback boom of the late 1960’s. This steadily increasing presence has followed the growing stylistic and market influence of American fantasy abroad dating from the initial translations of H.P. Lovecraft’s Arkham House collections in Spain, France, and Germany. The growth of the HPL cult abroad has boded well for other American exports of the Weird Tales school, and with the exception of the Lovecraft Mythos, the fantasy fiction of REH has proved the most popular, becoming an international literary phenomenon with translations and critical publications in Spain, Germany, France, Greece, Poland, Japan, and elsewhere. [1] All this shows how appealing REH’s exciting fantasy is across cultures, despite inevitable losses in stylistic impact through translations. Even so, there is sometimes enough enthusiasm among readers to generate fandom activities and publications. We have already covered those in France. [2] Now let’s take a look at some other countries. GERMANY, AUSTRIA, AND SWITZERLAND The first Howard stories published in German were in the fanzines Pioneer #25 and Lands of Wonder ‒ Pioneer #26 (Austratopia, Vienna) in 1968 and Pioneer of Wonder #28 (Follow, Passau, Germany) in 1969. -

Barbarians of Lemuria

Barbarians of Lemuria Barbarians of Lemuria Sword & Sorcery Role-playing Game Sample file “It is a savage age of sorcery and bloodshed, where strong men and beautiful women, warlords, priests, magicians and gladiators battle to carve a bloody path leading to the Throne of Lemuria. It is an age of heroic legends and valiant sagas too. And this is one of them…” The Crimson Edda i Acknowledgments Game design Simon Washbourne Artwork Cover: John Grumph Lemuria Map: Gill Pearce Interior: John Grumph, Keith Vaughn, Matthew Vasey Logo: Jerry Grayson Special thanks Michael Hill, Timothy Harper, Keith Vaughn, Mike Richards, Colin Chapman, Cameron Smith, Rich Spainhour, David Kot, Playtesters Annette Washbourne, Mark George, Alyson George, Nigel Uzzell, Janine Uzzell, Gary Collett, Leigh Wakefield, Ian Greenwood, Paul Simonet, Mike Richards, Alison Richards, Phil Ratcliffe, Robert Watkins, Rob Irwin, Michael Hill, members of IWARPUK. Influences Lin Carter: Thongor of Lemuria Robert. E. Howard: Conan the Barbarian, King Kull & Bran Mac Morn John Jakes: Brak the Barbarian C.L Moore: Jirel of Joiry Michael Moorcock: Elric of Melnibone Fritz Leiber: Fafhrd & The Grey Mouser Clark Ashton Smith: The Zothique Cycle and very many others Copyright notice Barbarians of Lemuria is Simon Washbourne Sample file BARBARIANS OF LEMURIA IS NOW AVAILABLE IN PRINT FROM CUBICLE 7 ENTERTAINMENT! ii Barbarians of Lemuria Contents Introduction The age of the sorcerer-kings ........................................................................................ Page -

By Lee A. Breakiron ONE-SHOT WONDERS

REHeapa Autumnal Equinox 2015 By Lee A. Breakiron ONE-SHOT WONDERS By definition, fanzines are nonprofessional publications produced by fans of a particular cultural phenomenon, such as a literary or musical genre, for the pleasure of others who share their interests. Readers themselves often contribute to fanzines by submitting their own articles, reviews, letters of comment, and fan fiction. Though the term fanzine only dates from 1940 when it was popularized within science fiction and comic book fandom, the first fanzines actually date back to at least the nineteenth century when, as a uniquely American development, literary groups formed amateur press associations or APAs in order to publish collections of poetry, fiction, and commentary. Few, if any, writers have had as many fanzines, chapbooks, and other ephemera dedicated to them as has Robert E. Howard. Howard himself self-published his own typed “zine,” The Golden Caliph of four loose pages in about August, 1923 [1], as well as three issues of one entitled The Right Hook in 1925 (discussed later). Howard collaborated with his friends Tevis Clyde “Clyde” Smith, Jr., and Truett Vinson in their own zines, The All-Around Magazine and The Toreador respectively, in 1923 and 1925. (A copy of The All-Around Magazine sold for $911 in 2005.) Howard also participated in an amateur essay, commentary, and poetry journal called The Junto that ran from 1928 to 1930, contributing 10 stories and 13 poems to 10 of the issues that survive. Only one copy of this monthly “travelogue” was circulated among all the members of the group. -

Ebook Download Conan Chronicles Epic Collection

CONAN CHRONICLES EPIC COLLECTION: THE BATTLE OF SHAMLA PASS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tim Truman | 472 pages | 14 Jan 2020 | Marvel Comics | 9781302921910 | English | New York, United States Conan Chronicles Epic Collection: The Battle Of Shamla Pass PDF Book Cail marked it as to-read Nov 02, This is the company that is ambushed and destroyed in the infamous Battle of Shamla Pass. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Want to Read saving…. In this article: Conan the Barbarian , Marvel. Combining Orders If you submit more than one order, we will automatically combine your orders and refund any excess shipping eBay charged you as long as we have not already processed your previous order. But what grotesque horrors await him in the Hall of the Dead? Sign up. This will likely increase the time it takes for your changes to go live. Then, a lingering curse follows Conan on his journey back to his homeland - and great darkness lies ahead in a doomed city! Consider supporting us and independent comics journalism by becoming a patron today! We are currently experiencing delays in processing and delivering online orders. View Product. Ernest Elias marked it as to-read Jun 03, Presenting all-action adaptations of classic Robert E. Contact Us for more info. Dec 28, Alex rated it it was amazing. Then he becomes the General of the Army for Princess Yasmela and eventually becomes the Lord of Amalr The fourth volume of the Epic Collection continues in the fine tradition of excellent story telling and great artwork of the previous volumes. -

Conan the Barbarian ______

In Defense of Conan the Barbarian ___________________________________ The Anarchism, Primitivism, & Feminism of Robert Ervin Howard Robert E. Howard has been the subject of numerous media, including several biographies and a movie. He is known and well-remembered as the creator of Conan the Cimmerian Kull of Atlantis, and the Puritan demon-hunter, Solomon Cane. His most famous creation by far, Conan has secured an immoveable foothold in the popular consciousness, and has created an enduring legacy for an author whose career lasted just over a decade. Unfortunately, due mostly to the Schwarzenegger films of the 80s, this legacy- the image of Conan in the public mind- is an undue blemish on a complex, intelligent character, and on Howard himself. In Defense of Conan the Barbarian seeks to invalidate these stereotypes, and to illuminate the social, political, economic, and ethical content of the Howard's original Conan yarns. ANTI-COPYRIGHT 2011 YGGDRASIL DISTRO [email protected] a new addition to Hyborian Scholarship by: yggdrasildistro.wordpress.com Please reprint, republish, & redistribute. ROWAN WALKINGWOLF "Barbarism is the natural state of mankind. Civilization is unnatural. It is a whim of circumstance. And barbarism must always ultimately triumph." "Is it not better to die honorably than to live in infamy? Is death worse than oppression, slavery, and ultimate destruction?" skeptical questions posed by José Villarrubia's in the beginning of Conan the Barbarian. Conan the Cimmerian. Conan, King of this essay: Aquilonia. Call him what you will, most everyone in contemporary Western society is familiar with this pulp icon to "I have often wondered..."What is the appeal of Conan the some extent. -

Towards a Cognitive Theory of (Canadian) Syncretic Fantasy By

University of Alberta The Word for World is Story: Towards a Cognitive Theory of (Canadian) Syncretic Fantasy by Gregory Bechtel A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English English and Film Studies ©Gregory Bechtel Fall 2011 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Abstract Unlike secondary world fantasy, such as that of J.R.R. Tolkien, what I call syncretic fantasy is typically set in a world that overlaps significantly with the contemporary "real" or cognitive majoritarian world in which we (i.e. most North Americans) profess to live our lives. In terms of popular publication, this subgenre has been recognized by fantasy publishers, readers, and critics since (at least) the mid 1980s, with Charles De Lint's bestselling Moonheart (1984) and subsequent "urban fantasies" standing as paradigmatic examples of the type. Where secondary world fantasy constructs its alternative worlds in relative isolation from conventional understandings of "reality," syncretic fantasy posits alternative realities that coexist, interpenetrate, and interact with the everyday real. -

The Man Behind the Sword Transcript

1 Imagine it’s the early 1980s, and a recent movie that you really liked was Conan the Barbarian. This was Arnold Schwarzenegger’s first bit role. It wasn’t The Terminator – that was ’84. Conan came out in ’82. WARLORD: Conan, what is best in life?” CONAN: To crush your enemies, see them driven before you, and to hear the lamentations of their women! He also could barely speak English, but that didn’t matter. Conan was cheesy fun and it spawned a ton of other movies and TV shows about beefcake, loincloth wearing, sword-wielding, indestructible action heroes. For the record, I loved that stuff as a kid in the ‘80s. In fact, my favorite cartoon at the time was Thundar the Barbarian. CLIP THUNDAR OPENING CREDITS If you were more intellectually curious than I was, and you wanted to know who came up with Conan? You might have gone to your local library or bookstore and found the original Conan stories written by Robert E. Howard in the 1930s. You might have also found the only biography about Howard at the time, which was called “Dark Valley Destiny” by L. Sprague DeCamp. The author of that biography, L. Sprague DeCamp, had been controlling Howard’s estate for years, although thought Howard was a hack. He described Howard’s writing as juvenile and careless, and DeCamp even wrote a number of the Conan stories. Howard had committed suicide in 1936 after learning that his mother was terminally ill. And DeCamp had been claiming for years in articles and in his biography of Howard had a massive Oedipal complex. -

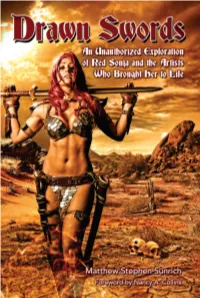

An Unauthorized Exploration of Red Sonja

RED SONJA and the ARTISTS WHO BROUGHT HER TO LIFE RED SONJA and the ARTISTS OF SWORDS: AN UNAUTHORIZED EXPLORATION DRAWN ince her debut in Marvel’s Conan the SBarbarian during the early years of the Bronze Age of Comics, Red Sonja, the scarlet-maned She-Devil with a Sword, has gone on to become the undisputed queen of sword and sorcery. She has hacked and slashed her way through more than 300 comic books to date—a number which continues to grow in the pages of Dynamite Entertainment’s various series. Here we MATTHEW STEPHEN SUNRICH MATTHEW explore her adventures and how they relate to other comics, as well as novels, television programs, and fi lms, and examine the work of the myriad artists whose pens and pencils gave her the breath of life. www.hassleinbooks.com Red Sonja©™ is the intellectual property of Luke D. Lieberman and Red Sonja LLC. No copyright infringement is intended or implied. Drawn Swords: An Unauthorized Exploration of Red Sonja and the Artists Who Brought Her to Life is a scholarly source-work that has not been licensed or authorized by any person or entity associated with Luke D. Lieberman and Red Sonja LLC. Drawn Swords: An Unauthorized Exploration of Red Sonja and the Artists Who Brought Her to Life By Matthew Stephen Sunrich Drawn Swords: An Unauthorized Exploration of Red Sonja and the Artists Who Brought Her to Life Copyright © 2017 Matthew Stephen Sunrich. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. -

Fantastyka a Realizm / the Fantastic and Realism

Wydawca: Temida 2 Przy współpracy i wsparciu finansowym Wydziału Filologicznego Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku Redaktor Naukowy Wydawnictwa Temida 2: Eugeniusz Ru śkowski Rada Naukowa Wydawnictwa Temida 2: Przewodnicz ący Rady Naukowej Wydawnictwa Temida 2: Rafał Dowgier Członkowie z Uniwersytetu w Białymstoku: Stanisław Bo żyk, Leonard Etel, Ewa M. Guzik- -Makaruk, Adam Jamróz, Dariusz Kijowski, Cezary Kosikowski, Cezary Kulesza, Jarosław Ławski, Agnieszka Malarewicz-Jakubów, Maciej Perkowski, Stanisław Prutis, Eugeniusz Ru śkowski, Walerian Sanetra, Joanna Sie ńczyło-Chlabicz, Ryszard Skarzy ński, Halina Świ ęczkowska, Jaroslav Volkonovski, Mieczysława Zdanowicz Członkowie z Polski: Marian Filar (Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika w Toruniu), Edward Gniewek (Uniwersytet Wrocławski), Lech Paprzycki (Sąd Najwy ższy) Członkowie zagraniczni: Lidia Abramczyk (Pa ństwowy Uniwersytet im. Janki Kupały w Grodnie, Białoru ś), Vladimir Bab čak (Uniwersytet w Koszycach, Słowacja), Renata Almeida da Costa (Uniwersytet La Salle, Brazylia), Chris Eskridge (Uniwersytet w Nebrasce, USA), José Luis Iriarte Ángel (Uniwersytet Navarra, Hiszpania), Marina Karasjewa (Uniwersytet w Worone żu, Rosja), Bernhard Kitous (Uniwersytet w Rennes, Francja), Martin Krygier (Uniwersytet w Nowej Południowej Walii, Australia), Petr Mrkyvka (Uniwersytet Masaryka, Czechy), Marcel Alexander Niggli (Uniwersytet we Fryburgu, Szwajcaria), Andrej A. Novikov (Pa ństwowy Uniwersytet w Sankt Petersburgu, Rosja), Sławomir Redo (Uniwersytet Wiede ński, Austria), Ro ścisław Radyszewski (Uniwersytet im. Tarasa Szewczenki w Kijowie, Ukraina), Bernd Schünemann (Uniwersytet w Monachium, Niemcy), Sebastiano Tafaro (Uniwersytet w Bari, Włochy), Wiktor Trinczuk (Kijowski Narodowy Handlowo-Ekonomiczny Uniwersytet, Ukraina) Żadna cz ęść tej pracy nie mo że by ć powielana i rozpowszechniana w jakiejkolwiek formie i w jakikolwiek sposób (elektroniczny, mechaniczny), wł ącznie z fotokopiowaniem – bez pisemnej zgody Wydziału Filologicznego UwB i wydawcy. Recenzenci: dr hab. -

“The Age Undreamed Of”: Reality and History in Robert E. Howard's Fantasy

| Przemysław Grabowski-Górniak “THE AGE UNDREAMED OF”: REALITY AND HISTORY IN ROBERT E. HOWARD’S FANTASY Abstract “Know, O prince, that between the years when the oceans drank Atlantis and the gleaming cities, and the years of the rise of the Sons of Aryas, there was an Age undreamed of.” Thus begins “The Phoenix on the Sword”, Robert E. Howard’s story that introduced the world to Conan the Cimmerian. Set in the Hyborian Age, a forgotten period of our World’s prehistory that has been imaginatively described in Howard’s essays, the adventures of his barbarian heroes are never far removed from reality and history. In fact, Howard pronounced Conan “the most realistic character [he] ever evolved” and made the tales of the Cimmeri- an’s exploits reflective of the real concerns of the early twentieth-century America. The aim of this article is to demonstrate the role that realism played in the creation of Robert E. How- ard’s Hyborian Age and the fantasy stories set in it. Key Words: fantastic, realism, fantasy, Conan, Robert E. Howard It might be safely assumed that fantasy is not among the literary genres typically associated with themes and plots that could generally be defined as re- alistic. The name “fantasy” is in itself indicatory of improbability and fictitious- ness, which is hardly a surprising assessment in regard to a genre known for its extensive use of magic, legendary artefacts, and multitudes of imaginary crea- tures. The post-Tolkienian fantasy fully embraces the fantastic, which most probably stems from it being hugely inspired by myths and folklore. -

The Hyborian Review Volume 1 Number 3 July 31, 1996 If You’Ll Keep Listening, We’Ll Keep Talking

The Hyborian Review Volume 1 Number 3 July 31, 1996 If you’ll keep listening, we’ll keep talking... Great REH Quotes From The Shadow Kingdom, by Robert E. Howard, Movie Talk a short story about Kull, the fabled Atlantean. Sorbo Lands First Lead Role in “Slay, Kull!” rasped the Pict’s voice. “They all be serpent men!” Feature Film "Kull the Conqueror" The rest was a scarlet maze. Kull saw the familiar Here’s what the Universal Studios Web page has to faces dim like fading fog and in their places gaped say about the upcoming movie: horrid reptilian visages as the whole band rushed forward. His mind was dazed but his giant body ‘Kevin Sorbo has just landed his first feature film faltered not. role in Universal Pictures action-adventure "Kull the Conqueror." He will be acting in the role of Kull. The singing of his sword filled the room, and the The project, based on a script by Charles Pogue and onrushing flood broke in a red wave. But they produced by Raffaella DeLaurentiis, is expected to surged forward again, seemingly willing to fling start filming next summer. No director has been their lives away in order to drag down the king. chosen, although Rob Cohen ("Dragonheart") and Hideous jaws gaped at him; terrible eyes blazed into Kevin Hooks ("Passenger 57") are rumored to be his unblinkingly; a frightful fetid scent pervaded the possibilities. atmosphere – the serpent scent that Kull had known in southern jungles. Swords and daggers leaped at ‘The "Kull the Conqueror" comic is distributed by him and he was dimly aware that they wounded him. -

The Chronicles of Kull Volume 5: Dead Men of the Deep and Other Stories Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE CHRONICLES OF KULL VOLUME 5: DEAD MEN OF THE DEEP AND OTHER STORIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bill Sienkiewicz,Sal Buscema,John Buscema,Marie Severin,Klaus Janson,Charles Vess,Butch Guice,Joe Rubenstein,Ernie Chan,John Beatty | 256 pages | 06 Mar 2012 | Dark Horse Comics,U.S. | 9781595829061 | English | Milwaukie, United States The Chronicles of Kull Volume 5: Dead Men of the Deep and Other Stories PDF Book Genre sword and sorcery Characters Brule; Chief Brule flashback ; Athela flashback, death ; Ba-Thak flashback, death Synopsis Brule avenges the honor of one of the women in his tribe. Ernie Chan ,. Retrieved 22 March Mikebo added it Jan 20, Edward Edward rated it it was amazing Sep 18, In " The Shadow Kingdom ", Kull has spent six months upon the Valusian throne and faces the first conspiracy against him. Kull will need the help of an enigmatic warrior woman, Laralei, and an unlikely ally in arms, Ridondo the minstrel, if he is to conquer a giant extradimensional creature, three scheming wizards, and the wizard's skull-headed master and again rule the Purple Kingdom! Paperback , pages. Howard stories, including several Kull stories. Kevin Dumcum rated it liked it Jul 20, Trivia About The Chronicles of Volume 4 - 1st printing. Kull was born into a tribe settled in the Tiger Valley of Atlantis. Keith rated it really liked it Aug 30, To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. London, United Kingdom: Bauer Media. Dallan Crossman marked it as to-read Jun 03, More filters. Sort order. Error rating book.