A S E F I Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Junkers G 38 Aerophilatelie

Katalog und Handbuch zu den Flügen der JUNKERS G 38 D-2000 und D-2500 Hubertus Hentschel Siemensstraße 10 40670 Meerbusch Tel. 02159 - 3084 FAX 02159 – 51808 eMail: [email protected] Die Junkers Ganzmetallflugzeuge G 38 Junkers G 38 D-2000 ( AZUR ) Werknummer 3301 G 38 di 06.11.29 JUNKERS D-2000 07.05.31 LUFT HANSA D-2000 06.07.33 DEUTSCHLAND D-2000 20.03.34 DEUTSCHLAND D-AZUR Besatzung Flugkapitän : Wilhelm Zimmermann * 24.02.1897 + 29.03.1956 2. Flugzeugf. : Otto Brauer * 16.10.1897 + 16.04.1976 : Paul Dierberg : Hans Etzold Steward : Arthur Howe Konstrukteure : Hugo Junkers * 03.02.1859 + 03.02.1935 : Ernst Zindel * 21.03.1897 + 10.10.1978 Passagiere : 9 Sitzplätze, 4 Liegeplätze : nach dem Umbau 30 Sitzplätze Junkers G 38 D-2500 ( APIS ) Werknummer 3302 G 38 ce, G 38 ci, G 38 fi 14.06.32 LUFT-HANSA D-2500 00.00.33 HINDENBURG D-2500 29.04.33 GENERALFELDMARSCHALL VON HINDENBURG D-2500 20.03.34 GENERALFELDMARSCHALL VON HINDENBURG D-APIS 00.04.40 GF-GG Besatzung Flugkapitän : Otto Brauer ( später Major ) 2. Flugzeugf. : Hans Etzold Funker : Heinrich Wiechers Maschinisten : Otto Rosinski, Willi Melzer, Heinrich Lauerwald Steward : Arthur Howe Konstrukteure : Hugo Junkers, Ernst Zindel Passagiere : 34 Fluggäste Das Gästebuch der JUNKERS G 38 ( D - 2500 ) Am 29.04.1933 wurde die JUNKERS G 38 ( D - 2500 ) auf den Namen Generalfeldmarschall von Hindenburg getauft. Der Name Hindenburg hatte bereits vorher auf dem Rumpf gestanden. Die Taufe nahm Reichsluftfahrtminister Hermann Göring im Beisein des greisen Reichspräsidenten Paul von Hindenburg vor. -

During World War Ii. New Insights from the Annual Audits of German Aircraft Producers

ECONOMIC GROWTH CENTER YALE UNIVERSITY P.O. Box 208629 New Haven, CT 06520-8269 http://www.econ.yale.edu/~egcenter/ CENTER DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 905 DEMYSTIFYING THE GERMAN “ARMAMENT MIRACLE” DURING WORLD WAR II. NEW INSIGHTS FROM THE ANNUAL AUDITS OF GERMAN AIRCRAFT PRODUCERS Lutz Budraß University of Bochum Jonas Scherner University of Mannheim Jochen Streb University of Hohenheim January 2005 Notes: Center Discussion Papers are preliminary materials circulated to stimulate discussions and critical comments. The first version of this paper was written while Streb was visiting the Economic Growth Center at Yale University in fall 2004. We are grateful to the Economic Growth Center for financial support. We thank Christoph Buchheim, Mark Spoerer, Timothy Guinnane, and the participants of the Yale economic history workshop for many helpful comments. Corresponding author: Prof. Dr. Jochen Streb, University of Hohenheim (570a), D- 70593 Stuttgart, Germany, E-Mail: [email protected]. This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network electronic library at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=661102 An index to papers in the Economic Growth Center Discussion Paper Series is located at: http://www.econ.yale.edu/~egcenter/research.htm Demystifying the German “armament miracle” during World War II. New insights from the annual audits of German aircraft producers by Lutz Budraß, Jonas Scherner, and Jochen Streb Abstract Armament minister Albert Speer is usually credited with causing the boom in German armament production after 1941. This paper uses the annual audit reports of the Deutsche Revisions- und Treuhand AG for seven firms which together represented about 50 % of the German aircraft producers. -

CASE FILE Co

CASE FILE co TECHIICAL LIEMORANUI.:S 1TATIONAL ADVISORY FOR AERONAUTICS No. 608 THE USE OF ELEKTRON MTAL liT AIRPLANE CONSTRUCTION By E. I. de Ridder Jahrbuoh 1929 der Wsenschaft1iohen Oesellschaft fi.r Lu±tfahrt This nmuua ON W* F** Nt R NATIONAL MWOlY COMM4!TI K* AEONAIrnr L&JIG1Y PVVOKIAL *€O$*tlT%C*t. LAaOPA7OPY LANG&.EY FIELD, MAM1N, VRIN*A TO ThLMOV€ *uø€: QUESTS R) P*iCAIONS SHOULD ,,Do(SstD Vasi ng to i-i I11Nk pmi*y coMMrcEE Mebruary, 1931 37$UMI'. N.W.. *INGTO$ • 2S. ).C. NATIONAL ADVISORY COITTEE FOR AERONAUTICS TECHNICAL 1MORANDUM NO. 608 THE USE OF ELEKTRON 1.rETAL IN AIRPLANE CONSTRUCTION* By E. I. de Ridder The tendency in aircraft construction is tovard higher per formanc:e. and gea.ter economy. From the , aerodynamic standpoint this me:ans a minimum possible drag by streamlining,. and from the structura]viewpo,nt, .aving in weight by usag light metal. Elektron is the lightest of the light metas, andas such merits our special attention beoaus .e it meets the demand for lighter construction. Itis impossible to go fully into its mechanical proper- ties and chemical composition on this occasion, but i .t should. not, be passed without at least briefly describing those charac- teristics which are of interest to the cpnstructor who uses it. E].elctron,. .as manufacT'cured ly the .1. G. Dye Industry, A.G., Bitterfeld,; isa magnesium-base alloy offrom 1.8 to 1.83 spe- cif'ic gravity.,. lience.a third as ligit as aluminum alloys. The rn I + .' eEg point of the metal is 625° slightly below that of aluminum. -

Junkers JU-87 Stuka Dive Bomber

Review of Junkers JU-87 Stuka Dive Bomber Created by Milviz Intro The JU-87 Sturzkampfflugzeug, alias “Stuka” is a Second World War German dive bomber built by Junkers. It features a twin seat tandem configuration where the back seat is a gunners position facing backwards. The D and G-series of JU-87 were both powered by a three-bladed Junkers Jumo 211J liquid-cooled inverted V12 engine powering 1420 PS (1,400hp) and was a notorious and feared aircraft of that era. One of the main characteristics of the Stuka was the inverted gull wings and the dive siren that spread fear in all troops under an attack. The Stuka was designed by Hermann Pohlman and had the first flight back in 1935. It quickly made it to the Luftwaffe’s Condor Legion where it became famous for its accuracy and effectiveness towards ground targets. However the Stuka was not very agile and was therefore very vulnerable in air-to-air combat situations. Several variants were built but this review will focus on the D5 and G2 versions. The D-version is the bomber version whereas the G-version was fitted with two 37mm (1.46in) cannons with armor-piercing tungsten carbide-cored ammunition. General Information & Aircraft Specs Produced by Junkers First Flight 17th of September 1935 Introduction 1936 Role Dive Bomber Status Retired in 1945 Built 6500 (estimated) Designer Hermann Pohlmann Primary User o Germany (The Luftwaffe) o Regia Aeronautica o Royal Romanian Air Force o Bulgarian Air Force Crew: 2 Power Plant: Junkers Jumo 211J Propeller: 3-bladed – 3.4m Wing Span: 13.80 m Wing Area: 31.90 m2 Empty Weight: 2,810 – 3,600 kgs MTOW: 5,100 – 5,720 kgs Max Speed: 344 – 354 km/h Never Exceed 600 km/h Range 1,000 – 1,165 km Armament: o 3x 7.92 machine guns o 4x 100kgs bombs (wing) (D) o 1x 500/1000 kgs bomb (center) (D) o 2x 37mm Flak 18 cannons (G) Purchase, Download & Installation I purchased the JU-87 Stuka through the www.FSPilotShop.com and as always the purchase and download went without any issues. -

Was Armament Minister Albert Speer Really Responsible for the German

Was armament minister Albert Speer really responsible for the German “armament miracle” during World War II? New doubts arising from the annual audits of the German aircraft producers. Jonas Scherner University of Mannheim Jochen Streb University of Hohenheim Abstract Armament minister Albert Speer is usually credited with causing the upswing in German armament production after 1941. Exploring the annual audit reports of the Deutsche Revisions- und Treuhand AG for six different firms, we question this view by showing that in the German aircraft industry the crucial political changes already occurred before World War II. The government decided in 1938 that aircraft producers had to concentrate on a few different types, and in 1937 cost-plus contracts were replaced with fixed price contracts. What followed was not a sudden production miracle but a continuous development which was fuelled by learning-by-doing and by the ongoing growth of the capital endowment. Preliminary version. Please do not quote. Comments are welcome. 1 The German armament miracle In December 1941 the Russian army stopped the German Wehrmacht near Moscow. That along with the United States’ entry into World War II brought the National Socialists’ strategy to fight so-called Blitzkriege, which could be waged with a comparatively low number of soldiers and arms, to a sudden end.1 Now confronted with the prospect of a long-lasting war against the Unites States and Soviet Russia, the German military planners acknowledged that they had to increase their armament production considerably. This insight was frankly made public by the economic journal Deutscher Volkswirt (1942, p. -

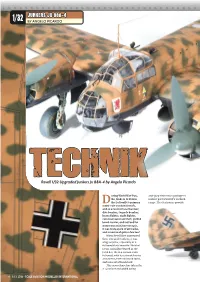

Junkers Ju 88A-4 1/32 Byby Sacco Angelo De Picardo Vries

JUNKERS JU 88A-4 1/32 BYBY SACCO ANGELO DE PICARDO VRIES TECHNIKRevell 1/32 Upgraded Junkers Ju 88A-4 by Angelo Picardo uring World War Two, and-play electronics package to the Junkers Ju 88 was make it part of Revell’s Technik D the Luftwaffe’s primary range. The electronics provide multi-role combat aircraft, and as a conventional bomber, dive bomber, torpedo bomber, heavy fighter, night fighter, reconnaissance aircraft, guided bomb carrier, and test bed for numerous aviation concepts, it was truly a jack of all trades, and a master of quite a few too! When Revell first announced their 1/32 scale Junkers, it was a big surprise, especially as it followed their beautiful Heinkel He 111. Initially released as the Ju 88 A-1, the A-4 variant soon followed, with its extra defensive armament, external bomb racks, and associated bomb load. This new release has taken the A-4 variant and added a plug- 6 • JULY 2018 • SCALE AVIATION MODELLER INTERNATIONAL 006-15-FEAT-Ju88-0718.indd 6 11/06/2018 13:55 1/32 The power pack of four AA batteries (not included) is external and has a power jack that allows it to be disconnected for transport. The various elements all connect together with push fittings and are colour-coded to ensure that decaling guides. All paint references Assembly Stages One to even a technophobe like me can’t are for Revell’s own range of paints, Thirty-two takes you through get it wrong. Supposedly...! though they are cross-referenced the assembly of the impressive The plastic parts are supplied to RLM colours where appropriate. -

Junkers Ju 87 G-2 494083/8474M

A/C SERIAL NO.G2 494083 SERIAL 2B INDIVIDUAL HISTORY JUNKERS Ju-87G-2 494083/8474M MUSEUM ACCESSION NUMBER 78/AF/657 Thought to have been built 1943-4 as one of 1,178 Ju87 D-5 ground-attack variants ordered, but later modified to G-2 standard, including fitting underwing mounting points for the two 37mm (1.46inch) Bk37/Flak 18 cannon carried by this variant. The werke number may have been changed from 2883 (D-5) to 494083 when rebuilt as a G-2, of which 210 were produced. (Reference: Aeroplane Monthly July 1976 - `Yesterday's Enemies' No.5, Ju87G). Hards (027926) suggests G-2 outer wings fitted to a D-3 ground attack variant airframe. c. May 45 Captured in Germany, possibly at a factory near the Russian border-Ju 87s remained operational on the Eastern Front until the end of the European war in May 1945. The British Disarmament Wing located 59 Ju-87s at the end of the war. Definitely later at Eggebek airfield, Schleswig-Holstein. Photo: War Prizes (DoRIS Ref.027726) p.151. Coded RI-JK (unidentified unit). This was one of 12 German aircraft selected by the Air Ministry for museum display, rather than as evaluation aircraft, so it did not receive an `Air Min' number. Nine of these museum aircraft still survive. 04 Sep 45 Left Eggebek by surface transport - not flown. Original markings retained for display purposes. Jan 46 Arrived at No.47 MU Sealand (Packing Depot) by this date for storage. 1947/48 Due to shortage of space at Sealand, moved to the German Air Force Equipment Centre located in five hangars at RAF Stanmore Park, Middx, along with other Air Historical Branch Aircraft and administered by No.4MU based at Ruislip from 1 Nov 1949, who provided a detachment of airmen for repairs to cased engines and aircraft. -

Junkers Ju87: from Dive-Bomber to Tank Buster 1935-45 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

JUNKERS JU87: FROM DIVE-BOMBER TO TANK BUSTER 1935-45 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Eddie J. Creek | 336 pages | 15 Dec 2012 | Crecy Publishing | 9781906537289 | English | Manchester, United Kingdom Junkers Ju87: From Dive-bomber to Tank Buster 1935-45 PDF Book Their numbers were low and ineffective in comparison to German operations. On 13 August the opening of the main German attacks on airfields took place; it was known to the Luftwaffe as Adlertag "Eagle Day". Im Only 8! Over the next 10 days, seven merchant ships were sunk or damaged, mainly in the Thames Estuary , for the loss of four Ju 87s. We will send you an email with instructions on how to reset your password. He was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for remaining at his post despite being mortally wounded. Testing was given two months and was to begin in February and end in April After the fall of France it was at used to attack shipping in the Channel. A long range version of the Ju 87B was also built, known as the Ju 87R, the letter being an abbreviation for Reichweite , " operational range". The D-3 was an improved D-1 with more armour for its ground-attack role. A Ju 87 B-2 is fitted with ski undercarriage to cope with the winter weather, 22 December Over Ju 87s had not been delivered and production was only 23 Ju 87 Ds per month out of the 40 expected. There are many aviation books published about the Junkers Ju dive bomber and tank killer. WFG received an official commendation. -

Power and Initiative in Twentieth Century Germany

POWER AND INITIATIVE IN TWENTIETH CENTURY GERMANY THE CASE OF HUGO JUNKERS by RICHARD WILLIAM EDWIN BYERS (Under the direction of John Morrow) ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the relationship between private enterprises and nation states in high technology research and applications. As the twentieth century progressed, this relationship became more contentious as state organs, citing national security priorities, attempted to assert their influence on private manufacturers. Nowhere is this relationship better illustrated than in the aircraft industry, and Germany’s geopolitical circumstances during the first half of the twentieth century provide an excellent framework to explore this intersection of interests. The dissertation focuses on the relationship between Professor Hugo Junkers and three successive state regimes in Germany between 1914 and 1934. Already a successful businessman and entrepreneur by the beginning of the First World War, Hugo Junkers continued to pursue plans for all- metal aircraft designs after war began despite wartime supply difficulties and widespread skepticism that such a craft would ever fly. Successful flight trials in 1915 lead to increased official interest in the Junkers firm as a possible military aircraft supplier, and military representatives began negotiations with Junkers over possible production of his aircraft designs. When these negotiations foundered, state officials accused Junkers of pursuing selfish objectives at the state’s expense, and increasingly intervened in the firm’s production processes. Professor Junkers fiercely resisted these incursions, and this resistance permanently damaged relations between the two parties. Throughout the life of the Weimar Republic, Junkers and state officials fought to control the firm’s production and design priorities. -

Die Letzten Junkers-Flugzeuge

Buchserie Die letzten Junkers-Flugzeuge, Paul eil III Zöller, PaulJunkers Ju86, Ju87, Ju88, Ju90 Zöller, Paul Zöller, Paul Die letztenund Junkers Baade -152Flugzeuge Die letzten Junkers-Flugzeuge Die letzten Junkers-Flugzeuge Teil I Teil II Teil III Frühe Junkers-Entwicklungen Junkers Ju 52, AAC.1 und CASA 352 Junkers Ju86, Ju87, Ju88, Ju90 Junkers J1 bis Junkers A50 und Baade 152 1. Auflage, September 2019 Paperback, 288 Seiten ISBN 978-3-7494-8172-9 http://www.bod.de/shop.html UVP 26,99 € 1. Edition, May 2017 1. Edition, June 2018 1. Edition, September 2019 Paperback, 158 pages Paperback, 268 pages Paperback, 288 pages ISBN 978-3-7431-1823-2 ISBN 978-3-7528-8016-8 ISBN 978-3-7494-8172-9 http://www.bod.de/shop.html http://www.bod.de/shop.html http://www.bod.de/shop.html UVP 15,99 € UVP 24,99 € UVP 26,99 € All books are written in German ! Herstellung und Vertrieb: Herausgeber: BoD – Books on Demand, Norderstedt Paul Zöller Luftfahrtarchive Bezugsquelle: www.luftfahrtarchive.bplaced.net http://www.bod.de/shop.html Buchserie Die letzten Junkers-Flugzeuge, Paul eil III Almost 30Junkers.000 Junkers Ju86, Ju87,aircraft Ju88,had Ju90been built by the Junkers company and their associated partner facilities during their 30 yearsundof existance Baade 152between 1915 and 1945. Most of these aircraft were built during World War II and were lost during their wartime utilization after only a few mission days. The few Junkers aircraft, which survived at the end of the war, consisted of valuable raw materials, which were urgently required during Europe‘s postwar reconstruction and were scrapped to gain these raw materials. -

Junkers G 38

Junkers Hugo Junkers - Ein Leben für die Technik. https://www.junkers.de Name: Junkers G 38 Leistung(kW): 2352 kW Verwendungszweck: Passagierflugzeug Leistung(PS): PS Baujahr: 1929 Spannweite: 44,00 m Besatzung: 7 Länge: 23,20 m Passagiere: 34 Höhe: 6,85 m Triebwerk: 4x Junkers L88a, später JUMO 204 A Flügelfläche: 305,00 qm Startmasse: 21200 kg Höchstgeschwindigkeit: 210 km/h Ein Aufsehen erregendes Ereignis war der Erstflug des viermotorigen Großverkehrsflugzeuges G 38 am 6. https://www.junkers.de/blog/flugzeuge/junkers-g-38/ 1 / 3 Junkers Hugo Junkers - Ein Leben für die Technik. https://www.junkers.de November 1929 in Dessau. Es war zu dieser Zeit das weltgrößte zivile Landflugzeug, ausgestattet mit zuerst je zwei Junkers-Motoren L 55 und L 8 a (Gesamtleistung 1470 kW/2000 PS). Das Flugzeug hatte leicht gepfeilte Tragflächen, das Flügelmittelstück nahm beidseitig je eine besonders bevorzugte Passagierkabine mit Blick in Flugrichtung auf. Die Flügelwurzel maß eine Profildicke von zwei Metern. Auffallend waren zudem das Kastenleitwerk und das gewaltige Tandemfahrwerk. Diese erste G 38 war registriert mit der Werknummer 3301 und der Kennung D-2000. Damit sind mehrere Weltrekorde geflogen worden. Der Erstflug fand am 6.November 1929 statt. Am 2. Mai 1930 stellte die “Deutsche Luft Hansa A.G.” (DLH) das Flugzeug in Dienst. Im Februar 1931 erfolgte in der Leipziger Junkers-Werft die erste Ummotorisierung auf nunmehr zwei L 8 a und zwei L 88 a (gesamt: 1764 kW / 2400 PS). Aus zuvor 13 Passagierplätzen wurden 19. Umbauten vom Oktober 1931 bis zum Sommer 1932 führten zur Aufstockung des Rumpfes; die Passagierplatzanzahl erhöhte sich auf 30, ein Zwischendeck entstand für zusätzliche Luftfracht. -

Bombing the European Axis Powers a Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945

Inside frontcover 6/1/06 11:19 AM Page 1 Bombing the European Axis Powers A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945 Air University Press Team Chief Editor Carole Arbush Copy Editor Sherry C. Terrell Cover Art and Book Design Daniel M. Armstrong Composition and Prepress Production Mary P. Ferguson Quality Review Mary J. Moore Print Preparation Joan Hickey Distribution Diane Clark NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page i Bombing the European Axis Powers A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945 RICHARD G. DAVIS Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 2006 NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page ii Air University Library Cataloging Data Davis, Richard G. Bombing the European Axis powers : a historical digest of the combined bomber offensive, 1939-1945 / Richard G. Davis. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-148-1 1. World War, 1939-1945––Aerial operations. 2. World War, 1939-1945––Aerial operations––Statistics. 3. United States. Army Air Forces––History––World War, 1939- 1945. 4. Great Britain. Royal Air Force––History––World War, 1939-1945. 5. Bombing, Aerial––Europe––History. I. Title. 940.544––dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Book and CD-ROM cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page iii Contents Page DISCLAIMER .