N Kaul at the LBF 09

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Famous Book Festivals List PDF

World Famous Book Festivals List PDF All companies and individuals are encouraged to read and understand each service, their policies, and then decide if they are a right fit for you. January ALA Philadelphia Midwinter Meeting and Exhibits, USA – https://2020.alamidwinter.org/ American Library Association Annual Conference, USA – https://www.combinedbook.com/2020-american-library-association-annual- conference.html Cairo International Book Fair, Egypt – http://www.cairobookfair.org.eg/opening/ Festival International De La Bande Dessinee, France – https://www.bdangouleme.com/ International Kolkata Book Fair, India – http://kolkatabookfair.net/ Jaipur Literature Festival, India – https://jaipurliteraturefestival.org/ New Delhi World Book Fair, India – http://nbtindia.gov.in/nbtbook February African American Children’s Book Fair, USA – http://theafricanamericanchildrensbookproject.org/ Amelia Island Book Festival, USA – https://www.ameliaislandbookfestival.org/ Brussels Book Fair, Belgium – https://flb.be/ California International Antiquarian Book Fair, USA – https://cabookfair.com/ Casablanca Book Fair, Morocco – https://www.salonlivrecasa.ma/fr/ Feria Internacional Del Libro De La Habana, Cuba – https://www.facebook.com/filcuba/ Havana International Book Fair, Cuba – https://www.internationalpublishers.org/component/rseventspro/event/196- havana-international-book-fair-havana-cuba Imagine Children’s Festival, United Kingdom – https://www.southbankcentre.co.uk/whats-on/festivals-series/imagine- childrens-festival Lahore International Book -

CQR Future of Books

Researcher Published by CQ Press, A Division of SAGE CQ www.cqresearcher.com Future of Books Will traditional print books disappear? he migration of books to electronic screens has been accelerating with the introduction of mobile reading on Kindles, iPhones and Sony Readers and the growing power of Google’s Book Search Tengine. Even the book’s form is mutating as innovators experiment with adding video, sound and computer graphics to text. Some fear a loss of literary writing and reading, others of the world’s storehouse of knowledge if it all goes digital. A recent settlement among Google, authors and publishers would make more out-of- Amazon’s Kindle 2 digital book reader can store print books accessible online, but some worry about putting such hundreds of books and read text aloud. Like the electronic Sony Reader, the Kindle features glare-free a vast trove of literature into the hands of a private company. text easier on the eyes than a computer screen. So far, barely 1 percent of books sold in the United States are electronic. Still, the economically strapped publishing industry is I under pressure to do more marketing and publishing online as N THIS REPORT S younger, screen-oriented readers replace today’s core buyers — THE ISSUES ......................475 I middle-aged women. BACKGROUND ..................484 D CHRONOLOGY ..................485 E CURRENT SITUATION ..........488 CQ Researcher • May 29, 2009 • www.cqresearcher.com AT ISSUE ..........................493 Volume 19, Number 20 • Pages 473-500 OUTLOOK ........................495 RECIPIENT OF SOCIETY OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISTS AWARD FOR EXCELLENCE ◆ AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION SILVER GAVEL AWARD BIBLIOGRAPHY ..................498 THE NEXT STEP ................499 FUTURE OF BOOKS CQ Researcher May 29, 2009 THE ISSUES OUTLOOK Volume 19, Number 20 MANAGING EDITOR: Thomas J. -

T He Best Estonian Children's Books of All Time

T HE BEST ESTONIAN CHILDren’s BOOKS OF ALL T IME CELEBRAT E W IT H US! ESTONIAN CHILDren’s 3+ Kätlin Vainola. Lift. Illustrated by Ulla Saar 4 LIT ERAT URE CENT RE Piret Raud. Mister Bird’s Story. Illustrated by the author 5 The small, innovative country of Estonia will be The Estonian Children’s Literature Centre is a specialised 6+ celebrating its centenary in 2018, and will also be a Market competency organisation that promotes the country’s Eno Raud. Raggie. Illustrated by Edgar Valter 6 Focus country at the London Book Fair for the first time most outstanding children’s works abroad. This includes Ellen Niit. Mr. Nightingale from Nightjar Street. Illustrated by Priit Pärn 8 ever. It goes without saying that now is the best time to representing Estonian children’s authors at the world’s Andrus Kivirähk. Poo and Spring. Illustrated by Heiki Ernits 10 take a closer look at Estonian children’s literature! largest book fairs, organising their appearances abroad, Ellen Niit. Pille-Riin’s Stories. Illustrated by Vive Tolli 12 Estonia has one of the world’s highest numbers of maintaining a database of Estonian children’s literature, Edgar Valter. The Poku Book. Illustrated by the author 14 children’s books published annually per capita. In 2016, and producing publications on the topic. The Centre close to 3,800 works (780 of which were children’s titles) collaborates on a large scale with publishers, researchers, 8+ Piret Raud. Slightly Silly Stories. Illustrated by the author 16 were published in the country, which has a population translators, teachers, and other specialists. -

Global Book Fair Report 2017

IPA Global Book Fair Report 2017 IPA Global Book Fair Report 2017 Contents: Introduction 03 AMERICAS 05 Special focus: Mexico 08 Guadalajara International Book Fair 09 AFRICA 11 Special focus: Nigeria 13 Nigeria International Book Fair 15 ASIA and OCEANIA 16 Special focus: South Korea 19 Seoul International Book Fair 20 EUROPE 21 Special focus: Greece 26 Thessaloniki International Book Fair 27 ALDUS network 28 MIDDLE EAST and CENTRAL ASIA 29 Special focus: Egypt 32 Cairo International Book Fair 33 IPA Global Book Fair Report 2017 Introduction Book fairs play a vital role in so- trade attendees, some are de- cieties. While public book fairs signed for the general public, promote books and reading, and others are hybrids, often their professional equivalents separating their fair into profes- allow publishers, agents, distrib- sional and public days, or utors and retailers to meet and providing separate areas. In do real business. They also Frankfurt, for instance, the first draw media and public attention three days are trade days while to the book industry and provide the public attends on the final platforms for authors to meet two days. In Geneva, there is a readers. Book fairs are a mo- special area dedicated to the ment where many creative pro- conferences for book profes- fessions converge. sionals. In an age when business is of- The main function of profes- ten done remotely, book profes- sional book fairs is to be a mar- sionals still believe that book ket place for trade profession- fairs have not lost their rele- als. Book rights are bought and vance. -

How Do I Start Planning My Book Marketing Campaign and Book Launch? | Schiel & Denver Book Publishers

How do I start planning my book marketing campaign and book launch? | Schiel & Denver Book Publishers In reality, you should start as soon as you are able. With Schiel & Denver's bi-annual trade catalog and international marketing strategy, you will have a constant background marketing to bookstores, pre-publication, but you can assist the work of our dedicated sales reps in the following areas: Start whipping up interest in your book early by undertaking to include in your marketing plan/campaign the following tasks and services, depending on your budget: 1. Brainstorming Session The key to successful marketing is to get everyone you know involved, and pool your resources. Write down your book's major selling points, and have a backcover blurb and short synopsis, so you have information ready to talk about and send to people via email. Think about your book's likely readership, and do whatever you can to get the word out. Sometimes well-connected authors can use old contacts, even work colleagues to help promote the book at events, conferences, exhibitions, anywhere where you can get a captive audience. Understand that even at traditional publishers, it's the authors who roll up their sleeves and get stuck into promotion are the ones who achieve the bestsellers. Marketing is not a passive process and like most things in life, your success depends upon how much effort you put in. 2. Word of mouth sales and Booksigning parties Many sales can be generated from personal recommendations of reading groups, booksellers, booksigning parties, attending literary festivals - indeed anywhere you can speak positively about your book. -

Success of the UAE Publishing Market Around the World

Success of the UAE Publishing Market around the World Over the past four decades, the UAE publishing industry has grown from a fledgling industry into a regional trade hub Timeline UAE gains independence; only 48% of the adult population is literate; 1971 38% literacy among females 1979 Number of books published in the UAE reaches 6 1980 Press and Publications Law introduced 1982 Sharjah International Book Fair held for the first time 1984 UAE Writers Union established 1992 Law on the Protection of Intellectual Works and Copyright introduced 1996 Signatory to the WTO TRIPS Agreement Signatory to the WIPO Copyright Treaty and the Berne Convention for the 2004 Protection of Literary and Artistic Works 2007 Abu Dhabi International Book Fair held for the first time in its new format 2009 Emirates Publishers Association (EPA) is established Emirates Intellectual Property Association and the UAE Board on Books 2010 for Young People established 2012 EPA becomes a full member of the International Publishers Association 2014 Book exports exceed $40 Million Literacy rate reaches 94% with literacy among females exceeding that of 2015 males by 2% Kalimat becomes first Emirati publishing house to win Bologna Children’s 2016 Book Fair Award Sharjah nominated as 2019 World Book Capital 2018 3 Sources: UNESCO Archives, Staff Analysis The Emirates Publishers Association is a national organization that was created to support capacity development of the UAE publishing industry EPA is a leading voice for change … … with 10 key priorities that guide its work . The Emirates Publishers Association (EPA) was established in 2009 1 Aligning key stakeholders to increase collaboration among publishing industry stakeholders to 2 Expanding markets address various industry challenges 3 Improving copyright and legal framework . -

BOOKEXPO and NEW YORK RIGHTS FAIR (NYRF) COLLABORATE to HELP GROW and IMPROVE the PUBLISHING INDUSTY

BOOKEXPO AND NEW YORK RIGHTS FAIR (NYRF) COLLABORATE TO HELP GROW and IMPROVE THE PUBLISHING INDUSTY LONDON, UK/ NORWALK, CT – April 11, 2018 – BookExpo and New York Rights Fair (NYRF) today announced a joint marketing agreement whereby NYRF will become the Official Rights Fair of BookExpo starting in 2018. The owners of NYRF, BolognaFiere, Publishers Weekly, and Combined Book Exhibit, will join forces with the owner of BookExpo, Reed Exhibitions, to collaborate in the best interest of improving and growing all aspects of the book industry. This joint marketing agreement will allow BookExpo and NYRF to work together to offer the entire publishing industry the perfect gateway to the US publishing market, including increased access to resurgent US bookstores, and more opportunities for rights professionals to embrace the explosion in new media and rights opportunities. The new relationship will help to bring together all aspects of the publishing industry, providing the strongest foundation for those looking to pursue publishing rights in the US and internationally. Starting in 2018, NYRF and BookExpo will work seamlessly together to offer the following to all attendees: NYRF badge holders will have full access to the BookExpo exhibition floor BookExpo’s Rights Center will move to NYRF and will become the official Rights Center of BookExpo. Rights oriented exhibitors will have the option to move to premium space at the NYRF located at the Metropolitan Pavillion in the Chelsea section of NYC BookExpo attendees with a Rights badge designation will have full access to NYRF Shuttle buses will be provided between BookExpo and NYRF to enable attendees to easily attend both events Information for both NYRF and BookExpo will be available in all directories and websites for both shows On-site staff will assist with information regarding BookExpo and NYRF at both events Antonio Bruzzone, General Director, BolognaFiere said: “This relationship was formed from the mutual goal of best serving the publishing industry. -

IPA World Book Fair Report 2016

IPA World Book Fair Report 2016 24.02.2016 Joanna Bazán Babczonek, Project & Office Manager Ben Steward, Director of Communications & Freedom to Publish 1. Introduction In 2015 the IPA released a special report on the Future of Book Fairs , (http://bit.ly/1S234If ) asking if they still bring value to modern publishing. The report found that book fairs are still the engine that keeps the wheels of publishing turning. In an age of video conferencing and digital networking, book fairs are a real-life moment that brings people in publishing together. Relationships are formed, contracts signed and hands shaken. Moreover, book fairs open a window on the publishing world, capturing public interest and drawing the attention of a media more concerned with publishing’s products than its mechanics. The 2016 IPA Book Fair Report looks at some of the world’s standout fairs, and asks the people behind them how they will stay ahead of the curve. The report is designed to help publishing professionals understand the evolution of book fairs and to guide their organizers towards an ever better performance of an essential service to publishers and publishing. 2. What are book fairs? All book fairs are not the same. Some are heavily consumer slanted, others more for publishing professionals. But whatever their target audience, their common goal is to showcase authors, books and brands, and connect suppliers with buyers. For example, the Salon du Livre de Genève , one of the francophone world’s leading book fairs, is almost entirely geared towards consumers. Effectively, it is a vast two-day bookshop, with retailers and publishers selling their wares side by side. -

The-Book-Collector-Example-2018-04.Pdf

641 blackwell’s blackwell’s rare books rare48-51 Broad books Street, 48-51 Broad Street, 48-51Oxford, Broad OX1 Street, 3BQ Oxford, OX1 3BQ CataloguesOxford, OX1 on 3BQrequest Catalogues on request CataloguesGeneral and subject on catalogues request issued GeneralRecent and subject subject catalogues catalogues include issued General and subject catalogues issued blackwellRecentModernisms, subject catalogues Sciences, include ’s Recent subject catalogues include blackwellandModernisms, Greek & Latin Sciences, Classics ’s rareandModernisms, Greek &books Latin Sciences, Classics rareand Greek &books Latin Classics 48-51 Broad Street, 48-51Oxford, Broad OX1 Street, 3BQ Oxford, OX1 3BQ Catalogues on request Catalogues on request General and subject catalogues issued GeneralRecent and subject subject catalogues catalogues include issued RecentModernisms, subject catalogues Sciences, include andModernisms, Greek & Latin Sciences, Classics and Greek & Latin Classics 641 APPRAISERS APPRAISERS CONSULTANTS CONSULTANTS 642 Luis de Lucena, Repetición de amores, y Arte de ajedres, first edition of the earliest extant manual of modern chess, Salamanca, circa 1496-97. Sold March 2018 for $68,750. Accepting Consignments for Autumn 2018 Auctions Early Printing • Medicine & Science • Travel & Exploration • Art & Architecture 19th & 20th Century Literature • Private Press & Illustrated Americana & African Americana • Autographs • Maps & Atlases [email protected] 104 East 25th Street New York, NY 10010 212 254 4710 SWANNGALLERIES.COM 643 Heribert Tenschert -

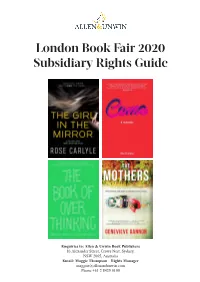

London Book Fair Rights Guide 2020

London Book Fair 2020 Subsidiary Rights Guide Enquiries to: Allen & Unwin Book Publishers 83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, Sydney, NSW 2065, Australia Email: Maggie Thompson – Rights Manager [email protected] Phone +61 2 8425 0100 Contents Fiction 5. The Girl in the Mirror - Rose Carlyle 6. The Family Doctor - Debra Oswald 7. The Mothers - Genevieve Gannon 8. Infinite Splendours - Sofie Laguna 9. The Deceptions - Suzanne Leal 10. Finding Eadie - Caroline Beecham 11. Death in Daylesford - Kerry Greenwood 12. Death in the Ladies’ Goddess Club - Julian Leatherdale 13. Red Dirt Country - Fleur McDonald 14. Fool Me Once - Karly Lane 15. The Farm at Pepper Tree Crossing - Leonie C. Kelsall 16. On a Barbarous Coast - Craig Cormick and Harold Ludwick Non-Fiction Memoir & Essays 18. Come - Rita Therese 19. Husna’s Story - Farid Ahmed 20. Through an Open Door - Miriam Lancewood 21. Max - Alex Miller 22. Sad Mum Lady - Ashe Davenport 23. She I Dare Not Name - Donna Ward 24. The Shah of Grey Lynn - Ghazaleh Golbakhsh 25. Not That I’d Kiss a Girl - Lil O’Brien 26. This Farming Life - Tim Saunders Books to Help You Live Better 27. STOIC - Andrew Charlton and Brigid Delaney 28. Your Mind is a Muscle - Dr Rachel Thomas 29. The Book of Overthinking - Gwendoline Smith 30. Slowtopia - Brooke McAlary 31. HOW TO GET TO $@# SLEEP! - Bernice Tuffery 32. 52 New Things in 52 Weeks - Lauren Keenan 33. Your Money Type - Melissa Browne 34. Mission Focus - Bram Connolly 35. Touching a Chord - Dr Anita Collins 36. Balance & Other B.S. - Felicity Harley 2 Contents 37. -

Publishingperspectives LONDON BOOK FAIR ISSUE

publishingperspectives 11 April 2011, london uK www.publishingperspectives.com london book fair issue Gail Force Where am I? Mehta-data Track one of the Answer: LBF, not See what’s on Sonny’s Where’s Patrick? most successful Frankfurt. Negotiate mind right now Mad Men Missed a deal? Let CEOs around Earls Court’s odd Who’s just paid Patrick Janson-Smith the aisles shape with this how much cheer you up Stand Nav app for what? Agency Model Jackal Feeling lonely? Gives Fun pursuit game. addresses in Soho/King’s There’s an agent Cross area. All credit on the loose, and cards accepted he’s hungry! Infringe Google See rights Book Search violations as OMG WTF! they happen I thought the globally in Yanks were real time looking after this? Haven’ta READ INSIDE: Cluedo • UK Rights Pros Talk Shop E-rights for • The Indian Invitation dummies • Brazil: Country of the Future Ivy-eye • Opportunities in the Middle East Live webcam at the celebrated • The Rebirth of the restaurant. Who’s Russian Lit Mag racking up their • 60 Years of Int’l Book Fairs expenses? • What’s Lost in Translation • and much, much more! iPlod The digital policeman USING TWITTER? from Apple. Vibrates if Fume someone tries to sell Follow our tweets: Where can I content outside the @pubperspectives smoke? (try app store France) In-depth international publishing news, served daily - Subscribe for FREE at www.publishingperspectives.com UK Rights Pros Talk Shop A Day in the Pitch of . with Roger Tagholm Lisa Baker Lucy Luck Andy Hine Harriet Sanders Head of Rights, Faber Lucy Luck Associates Foreign Rights Director, Little, Brown Rights Director, Pan Macmillan “Increasingly “I’m fas- “I’ve done “What’s con- we’re getting cinated by e- about 16 LBFs stantly on my requests for e- books and don’t and for me it’s mind is how book addenda. -

The Editor's Place

LOGOS 11(3) crc 17/10/00 11:24 am Page 116 LOGOS THE EDITOR’S PLACE Our “Books that Shaped the Century” project and will be the subject of a seminar for post-gradu- reached its dénouement with exhibits at the Frank- ate students in the fall of this year. furt Book Fair 1999 and the London Book Fair The last words on this venture come 2000, at both of which it attracted extensive public appropriately from our readers and from visitors to and media interest. The Bookseller, Publishing News the exhibits, who were invited both to comment and the Börsenblatt carried feature stories. “How and to nominate titles which they think should nice to see an exhibit at Frankfurt which is not have been included. The list was never meant to be commercial,” said one visitor. Another asked us exclusive. It was the result of a vote exercised by what we were selling. Hundreds browsed and took our panel. Inevitably, the cumulative personal views away copies of our descriptive booklet. of the panel affected the outcome. We all had Each book was displayed adjacent to the favourite titles which didn’t make the grade and we text written by Dick Abel, as set out in 10/3. The were all surprised that some titles of which (at least display was in chronological order, starting with speaking for myself) we had never heard, received Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim and Sigmund Freud’s The substantial support. Interpretation of Dreams, published in 1900, and fin- When I made my own initial list six years ishing with Nelson Mandela’s Long Walk to Free- ago, I tried to distance myself from books which dom, published in 1994.