Understanding the War in Yemen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNESCO Condemns Killing of Journalists Assassinated Journalists in Yemen

UNESCO Condemns Killing of Journalists Assassinated Journalists in Yemen Omar Ezzi Mohammad Radio engineer Ali Aish Mohammad Youssef Jamaie Abdullah Musib Security guards (Yemeni) Employees of radio station Al-Maraweah Killed on 16 September 2018 UNESCO Statement Ahmed al-Hamzi (Yemeni) Journalist Killed on 30 August 2018 in Yemen UNESCO Statement Anwar al-Rakan (Yemenit) Journalist Killed in Yemen on 2 June 2018 [UNESCO Statement] Abdullah Al Qadry (Yemenit) News photographer and camera operator Killed on 13 April 2018 [UNESCO Statement] Mohammad al-Qasadi (Yemenit) Photographer Killed on 22 January 2018 [UNESCO Statement] Sa’ad Al-Nadhari (Yemeni) Photojournalist Killed on 26 May 2017 in Yemen [UNESCO Statement] Wael Al-Absi (Yemeni) Photojournalist Killed on 26 May 2017 in Yemen [UNESCO Statement] 1 UNESCO Condemns Killing of Journalists Assassinated Journalists in Yemen Taqi Al-Din Al-Huthaifi (Yemeni) Photojournalist Killed on 26 May 2017 in Yemen [UNESCO Statement] Mohammed al-Absi (Yemeni) Led investigative reports in Yemen for several news outlets Killed on 20 December 2016 in Yemen [UNESCO Statement] Awab Al-Zubairi (Yemeni) Photographer for Taiz News Network Killed on 18 November 2016 in Yemen [UNESCO Statement] Mubarak Al-Abadi (Yemeni) Contributor to Al Jazeera television and Suhail TV Killed on 5 August 2016 in Yemen [UNESCO Statement] Abdulkarim Al-Jerbani (Yemeni) Photographer and reporter for several media in Yemen Killed on 22 July 2016 in Yemen [UNESCO Statement] Abdullah Azizan (Yemeni) Correspondent for the online -

Nowhere Safe for Yemen's Children

NOWHERE SAFE FOR YEMEN’S CHILDREN The deadly impact of explosive weapons in Yemen 2 Saudi Arabia Oman SA’ADA HADRAMAUT Sa’ada AL MAHARAH AL JAWF AMRAN HAJJAH YEMEN Amran AL MAHWIT MARIB Sana’a SANA’A Arabian Sea AL HODIDAH Hodeida SHABWAH R AYMAH DHAMAR AL BAYDA IBB AL DHALE’E ABYAN Taizz Al Mokha TAIZZ LAHJ Red Sea ADEN Aden Gulf of Aden INTRODUCTION The daily, intensive use of explosive weapons deaths and injuries during the second quarter of 2015 in populated areas in Yemen is killing and were caused by air strikes by the Saudi-led coalition, maiming children and putting the futures and 18% of child deaths and 17% of child injuries were of children at ever-increasing risk. These attributed to Houthi forces.3 weapons are destroying the hospitals needed to treat children, preventing medical supplies, food, fuel and other essential supplies “I was playing in our garden when the missile hit my from reaching affected populations and house. My mum, brother and sister were inside. hampering the day-to-day operations of “I ran to my mother but the missile hit the building as humanitarian agencies. she was trying to get out with my brother and sister. I saw my mum burning in front of me. Then I fell down, Before March 2015, life for children in Yemen was and later I found myself in the hospital and my body not without challenges: nearly half of young children was injured. I didn’t find my mum beside me as always. 1 suffered from stunting or chronic malnutrition. -

Securing the Belt and Road Initiative: China's Evolving Military

the national bureau of asian research nbr special report #80 | september 2019 securing the belt and road initiative China’s Evolving Military Engagement Along the Silk Roads Edited by Nadège Rolland cover 2 NBR Board of Directors John V. Rindlaub Kurt Glaubitz Matt Salmon (Chairman) Global Media Relations Manager Vice President of Government Affairs Senior Managing Director and Chevron Corporation Arizona State University Head of Pacific Northwest Market East West Bank Mark Jones Scott Stoll Co-head of Macro, Corporate & (Treasurer) Thomas W. Albrecht Investment Bank, Wells Fargo Securities Partner (Ret.) Partner (Ret.) Wells Fargo & Company Ernst & Young LLP Sidley Austin LLP Ryo Kubota Mitchell B. Waldman Dennis Blair Chairman, President, and CEO Executive Vice President, Government Chairman Acucela Inc. and Customer Relations Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA Huntington Ingalls Industries, Inc. U.S. Navy (Ret.) Quentin W. Kuhrau Chief Executive Officer Charles W. Brady Unico Properties LLC Honorary Directors Chairman Emeritus Lawrence W. Clarkson Melody Meyer Invesco LLC Senior Vice President (Ret.) President The Boeing Company Maria Livanos Cattaui Melody Meyer Energy LLC Secretary General (Ret.) Thomas E. Fisher Long Nguyen International Chamber of Commerce Senior Vice President (Ret.) Chairman, President, and CEO Unocal Corporation George Davidson Pragmatics, Inc. (Vice Chairman) Joachim Kempin Kenneth B. Pyle Vice Chairman, M&A, Asia-Pacific (Ret.) Senior Vice President (Ret.) Professor, University of Washington HSBC Holdings plc Microsoft Corporation Founding President, NBR Norman D. Dicks Clark S. Kinlin Jonathan Roberts Senior Policy Advisor President and Chief Executive Officer Founder and Partner Van Ness Feldman LLP Corning Cable Systems Ignition Partners Corning Incorporated Richard J. -

Led Military Coalition 36 EU Moves Towards an Arms Embargo on the Saudi-Led Military Coalition 37 MBZ Meets Macron in Paris, Protests Ensue 38

The NOVEMBER 2018 Yemen Review The Yemen Review The Yemen Review Launched in June 2016, The Yemen Review – formerly known as Yemen at the UN – is a monthly publication produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies. It aims to identify and assess current diplomatic, economic, political, military, security, humanitarian and human rights developments related to Yemen. In producing The Yemen Review, Sana’a Center staff throughout Yemen and around the world gather information, conduct research, hold private meetings with local, regional, and international stakeholders, and analyze the domestic and international context surrounding developments in and regarding Yemen. This monthly series is designed to provide readers with a contextualized insight into the country’s most important ongoing issues. Residents in the Tha’abat area of Taiz City inspect a home in November that was damaged by shelling from Houthi forces Photo Credit: Anas Alhajj The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally. Copyright © Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies 2018 CONTENTS Executive Summary 30 The Sana'a Center Editorial 31 Yemen’s War Profiteers Are Potential Spoilers of the Peace Process 31 UN-led Peace Talks Restart As Security -

Press in Yemen Faces Extinction Report

Report PRESS IN YEMEN FACES EXTINCTION JOURNALISTS NEED SUPPORT A report by Mwatana Organisation for Human Rights and the Gulf )Centre for Human Rights )GCHR www.mwatana.org June 2017 Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 5 VIOLATIONS LEADING TO DEATH .................................................................................... 6 ARBITRARY DETENTION AND ENFORCED DISAPPEARANCE ................................. 10 TORTURE ............................................................................................................................... 11 JUDICIAL ATTACKS ............................................................................................................. 13 LEGAL FRAMEWORK ........................................................................................................ 14 CONCLUSION ....................................................................................................................... 15 RECOMMENDATIONS ......................................................................................................... 16 INTRODUCTION Yemeni journalists are isolated and desperately need the support of the international community. After more than two years of conflict causing approximately 8,000 deaths, 42,000 injuries in addition to a humanitarian disaster, the press in Yemen remains committed against all the odds to reporting the truth. Journalists have been subject to systematic patterns of arbitrary -

Migration To, from and in the Middle East and North Africa Data Snapshot

Migration to, from and in the Middle East and North Africa1 Data snapshot Prepared by IOM Regional Office for the Middle East and North Africa, August 2016 Highlights The number of international migrants, including registered refugees, in the MENA region reached 34.5 million in 2015, rising by 150% from 13.4 million in 1990. In contrast, global migrant stocks grew by about 60% over the same period. Just over one third of all migrant stocks in the region are of people from other MENA countries. Emigrants from MENA account for 10% of migrant stocks globally, and 53% of emigrants from MENA countries remain in the region. The MENA region is the largest producer of refugees worldwide, with over 6 million refugees originating in MENA at the end of 2015. Now reaching nearly 4.9 million, refugees from the Syrian Arab Republic make up 30% of refugees globally. The MENA region hosts 18% of the world’s refugees, with about 60% of refugees in the region hosted by Lebanon and Jordan. In addition to refugees, there are roughly 16.4 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the MENA region. At the end of 2015, internal displacement in MENA accounted for roughly 40% of all internal displacement due to conflict and violence worldwide. New displacement in 2015 in Yemen, the Syrian Arab Republic and Iraq accounted for over half of all new displacement due to conflict and violence globally. International migrants in the MENA region, 2015 34.5 million international migrants, including registered refugees, were residing in the MENA region in 2015, according to the latest data on international migration stocks published by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; this represents 14% of the global migrant stock. -

Explosive Weapons in Yemen

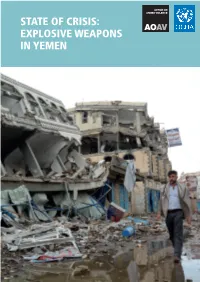

STATE OF CRISIS: EXPLOSIVE WEAPONS IN YEMEN ABOUT UN OCHA The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is the part of the United Nations Secretariat responsible for bringing together humanitarian actors to ensure a coherent response to emergencies. OCHA also ensures that there is a framework within which each actor can con - tribute to the overall response effort. OCHA’s core functions are coordination, policy, advocacy, information management and humanitarian financing. Our mission is to: • Mobilize and coordinate effective and principled humanitarian action in partnership with national and international actors in order to alleviate human suffering in disasters and emergencies; • Advocate the rights of people in need; • Promote preparedness and prevention; and • Facilitate sustainable solutions. OCHA has a unique mandate to speak out on behalf of the people worst affected by humanitarian situations. Our ultimate goal is to save more lives and reduce the impact of conflicts and natural disasters. ABOUT AOAV Action on Armed Violence (AOAV) is a UK-based charity working to reduce harm and to rebuild lives affected by armed violence. AOAV works with communities affected by armed violence, remove the threat of weapons, reduce the risks that provoke violence and conflict, and support the recovery of victims and Report by: survivors. Robert Perkins AOAV’s global explosive violence monitor, launched in October 2010, tracks the incidents, deaths Editors: and injuries from explosive weapon use reported in English-language media sources. AOAV does Hannah Tonkin, Iain Overton not attempt to comprehensively capture every incident of explosive weapon use around the world, but to serve as a useful indicator of the scale and pattern of harm to civilians. -

I. the Informal Economy

2016 2016 Report Team Background and Regional Papers: Ziad Abdel Samad (Executive Director, Arab NGO Network for Development), Roberto Bissio (Coordinator, Social Watch In- ternational Secretariat), Samir Aita (President, Cercle des Economistes Arabes), Dr. Martha Chen and Jenna Harvey (WIEGO Network), Dr. Mohamed Said Saadi (Political Economy Professor and Researcher), Dr. Faouzi Boukhriss (Sociology Professor, Ibn Toufail University, Qunaitira, Morocco), Dr. Howaida Adly (Political Sciences Professor, National Center for Sociological and Criminilogical Research, Egypt), Dr. Azzam Mahjoub (University Professor and International Expert), ANND works in 12 Arab countries with 9 national networks (with an extended membership Mohamed Mondher Belghith (International Expert), Shahir George (Independent of 250 CSOs from different backgrounds) and 23 NGO members. Researcher). P.O.Box: 4792/14 | Mazraa: 1105-2070 | Beirut, Lebanon National Reports: Dr. Moundir Alassasi (Job Market and Social Protection in the Tel: +961 1 319366 | Fax: +961 1 815636 Arab World Researcher and Expert), Dr. Khaled Minna (Job Market Researcher and www.annd.org – www.csrdar.org Expert), Dr. Hassan Ali al-Ali (Independent Researcher, Bahrain), Dr. Reem Adbel Halim (Independent Researcher, Egypt), Saoud Omar (Unionist and Consultant to the International Industrial Union, Egypt), Hanaa Abdul Jabbar Saleh (National Accounts Expert, Iraq), Ahmad Awad (Phenix Center for Economic and Informat- ics Studies, Jordan), Rabih Fakhri (Independent Researcher, Lebanon), Moham- med Ahmad al-Mahboubi (Development, Media, and Gender Studies Expert and Consultant, Mauritania), Dr. Faouzi Boukhriss (Sociology Professor, Ibn Toufail University, Qunaitira, Morocco), Firas Jaber (Founder and Researcher, al-Marsad, Palestine), Iyad Riyahi (Founder and Researcher, al-Marsad, Palestine), Dr. Hassan Ahmad Abdel Ati (National Civil Forum, Sudan), Dr. -

State of Crisis: Explosive Weapons in Yemen

STATE OF CRISIS: EXPLOSIVE WEAPONS IN YEMEN ABOUT UN OCHA The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is the part of the United Nations Secretariat responsible for bringing together humanitarian actors to ensure a coherent response to emergencies. OCHA also ensures that there is a framework within which each actor can con- tribute to the overall response effort. OCHA’s core functions are coordination, policy, advocacy, information management and humanitarian financing. Our mission is to: • Mobilize and coordinate effective and principled humanitarian action in partnership with national and international actors in order to alleviate human suffering in disasters and emergencies; • Advocate the rights of people in need; • Promote preparedness and prevention; and • Facilitate sustainable solutions. OCHA has a unique mandate to speak out on behalf of the people worst affected by humanitarian situations. Our ultimate goal is to save more lives and reduce the impact of conflicts and natural disasters. ABOUT AOAV Action on Armed Violence (AOAV) is a UK-based charity working to reduce harm and to rebuild lives affected by armed violence. AOAV works with communities affected by armed violence, remove the threat of weapons, reduce the risks that provoke violence and conflict, and support the recovery of victims and Report by: survivors. Robert Perkins AOAV’s global explosive violence monitor, launched in October 2010, tracks the incidents, deaths Editors: and injuries from explosive weapon use reported in English-language media sources. AOAV does Hannah Tonkin, Iain Overton not attempt to comprehensively capture every incident of explosive weapon use around the world, but to serve as a useful indicator of the scale and pattern of harm to civilians. -

Education and Security a Global Literature Review on the Role Of

Education and Security A global literature review on the role of education in countering violent religious extremism RATNA GHOSH ASHLEY MANUEL W.Y. ALICE CHAN MAIHEMUTI DILIMULATI MEHDI BABAEI 1 2 Contents Chapter 1: Introduction Context and Background 9 The Importance of Education for Security 12 Conclusion 15 Chapter 2: The Use of Education to Promote Extremist Worldviews Attacks on Educational Institutions 17 How Education is Used to Promote Violent Extremism 18 Educational Strategies for Recruitment and Promotion 18 Case Studies of Extremist Groups 24 Educational Backgrounds of Extremists 32 Problems with Other Forms of Education 34 Conclusion 35 Chapter 3: The Use of Education to Counter Violent Extremism How Education Can Counter Violent Extremism 37 Formal Education for CVE 38 Non-Formal Education for CVE 48 Evaluation 57 Conclusion 57 Chapter 4: Findings and Recommendations Major Findings 59 Gaps and Future Priorities 63 Final Remarks 65 Bibliography 67 Note This report was first published in February 2016. The research was commissioned by the Tony Blair Faith Foundation. The work of the Tony Blair Faith Foundation is now carried out by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. 3 ACRONYMS AQAP: al-Qaeda in the Arabian ITIC: The Meir Amit Intelligence and UN: United Nations Peninsula Terrorism Information Center, Israel UNESCO: United Nations AQI: al-Qaeda in Iraq IWPR: Institute for War and Peace Educational, Scientific and Cultural Reporting, London, UK Organisation, Paris, France AQIM: al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb KAICIID: -

Politics and Governance Open Access Journal | ISSN: 2183-2463

Politics and Governance Open Access Journal | ISSN: 2183-2463 Volume 5, Issue 2 (2017) MultidisciplinaryMultidisciplinary StudiesStudies inin PoliticsPolitics andand GovernanceGovernance Editors Amelia Hadfield, Andrej J. Zwitter, Christian Haerpfer, Kseniya Kizilova, Naim Kapucu Politics and Governance, 2017, Volume 5, Issue 2 Multidisciplinary Studies in Politics and Governance Published by Cogitatio Press Rua Fialho de Almeida 14, 2º Esq., 1070-129 Lisbon Portugal Academic Editors Amelia Hadfield, Canterbury Christ Church University, UK Andrej J. Zwitter, University of Groningen, The Netherlands Christian Haerpfer, University of Vienna, Austria Kseniya Kizilova, Institute for Comparative Survey Research, Austria Naim Kapucu, Naim Kapucu University of Central Florida, USA Editors-in-Chief Amelia Hadfield, Canterbury Christ Church University, UK Andrej J. Zwitter, University of Groningen, The Netherlands Available online at: www.cogitatiopress.com/politicsandgovernance This issue is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY). Articles may be reproduced provided that credit is given to the original andPolitics and Governance is acknowledged as the original venue of publication. Table of Contents Brexit and Devolution in the United Kingdom Michael Keating 1–3 Trust and Tolerance across the Middle East and North Africa: A Comparative Perspective on the Impact of the Arab Uprisings Niels Spierings 4–15 The Effect of Direct Democratic Participation on Citizens’ Political Attitudes in Switzerland: The Difference between Availability and Use Anna Kern 16–26 Towards Exit from the EU: The Conservative Party’s Increasing Euroscepticism since the 1980s Peter Dorey 27–40 Mixed Signals: Democratization and the Myanmar Media Tina Burrett 41–58 The State of Jordanian Women’s Organizations—Five Years Beyond the Arab Spring Peter A. -

Risk Factors Associated with the Recent Cholera Outbreak in Yemen: a Case-Control Study

Open Access Volume: 41, Article ID: e2019015, 6 pages https://doi.org/10.4178/epih.e2019015 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Risk factors associated with the recent cholera outbreak in Yemen: a case-control study Fekri Dureab1, Albrecht Jahn2, Johannes Krisam3, Asma Dureab4, Omer Zain5, Sameh Al-Awlaqi1,6, Olaf Müller2 1The Modern Social Association, Aden, Yemen; 2Heidelberg Institute of Global Health, Heidelberg University School of Medicine, Heidelberg, Germany; 3Institute of Medical Biometry and Informatics, Heidelberg University School of Medicine, Heidelberg, Germany; 4Health and Education Association for Development (SAWT), Aden, Yemen; 5Community Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, University of Aden, Aden, Yemen; 6Institute of Public Health, Jagiellonian University Medical College, Krakow, Poland OBJECTIVES: The cholera outbreak in Yemen has become the largest in the recent history of cholera records, having reached more than 1.4 million cases since it started in late 2016. This study aimed to identify risk factors for cholera in this outbreak. METHODS: A case-control study was conducted in Aden in 2018 to investigate risk factors for cholera in this still-ongoing outbreak. In total, 59 cholera cases and 118 community controls were studied. RESULTS: The following risk factors were associated with being a cholera case in the bivariate analysis: a history of travelling and having had visitors from outside Aden Province; eating outside the house; not washing fruit, vegetables, and khat (a local herbal stimulant) before consumption; using common-source water; and not using chlorine or soap in the household. In the multivari- ate analysis, not washing khat and the use of common-source water remained significant risk factors for being a cholera case.