The Clearing House Arrangement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Anti-Deprivation Rule and the Pari Passu Rule in Insolvency

The Anti-deprivation Rule and the Pari Passu Rule in Insolvency Peter Niven* In 2011 the UK Supreme Court delivered a judgment in Belmont Park Investments Pty v BNY Corporate Trustee Services Ltd that addressed the common law anti-deprivation rule. The anti-deprivation rule is a rule that is aimed at attempts to withdraw an asset on bankruptcy, with the effect that the bankrupt’s estate is reduced in value to the detriment of creditors. The underlying public policy is that parties should not be able to contract to defeat the insolvency laws. The Supreme Court in Belmont recognised, for the first time, that there are two distinct rules arising from that public policy, the anti-deprivation rule and the pari passu rule. The latter rule provides that parties cannot contract out of the statutory provisions for pari passu distribu- tion in bankruptcy. The Supreme Court’s judgment has been applied in a number of cases in the UK.This article examines Belmont and its application in two subsequent cases. 0There is a general principle of public policy that parties cannot contract out of the legislation governing insolvency. From this general principle two sub-rules have emerged: the anti-deprivation rule and the rule that it is contrary to public policy to contract out of pari passu distribution (the pari passu rule). The anti-deprivation rule is a rule of the common law that is aimed at attempts to withdraw an asset on bankruptcy, with the effect that the bankrupt’s estate is reduced in value to the detriment of creditors. -

Neil Cloughley, Managing Director, Faradair Aerospace

Introduction to Faradair® Linking cities via Hybrid flight ® faradair Neil Cloughley Founder & Managing Director Faradair Aerospace Limited • In the next 15 years it is forecast that 60% of the Worlds population will ® live in cities • Land based transportation networks are already at capacity with rising prices • The next transportation revolution faradair will operate in the skies – it has to! However THREE problems MUST be solved to enable this market; • Noise • Cost of Operations • Emissions But don’t we have aircraft already? A2B Airways, AB Airlines, Aberdeen Airways, Aberdeen Airways, Aberdeen London Express, ACE Freighters, ACE Scotland, Air 2000, Air Anglia, Air Atlanta Europe, Air Belfast, Air Bridge Carriers, Air Bristol, Air Caledonian, Air Cavrel, Air Charter, Air Commerce, Air Commuter, Air Contractors, Air Condor, Air Contractors, Air Cordial, Air Couriers, Air Ecosse, Air Enterprises, Air Europe, Air Europe Express, Air Faisal, Air Ferry, Air Foyle HeavyLift, Air Freight, Air Gregory, Air International (airlines) Air Kent, Air Kilroe, Air Kruise, Air Links, Air Luton, Air Manchester, Air Safaris, Air Sarnia, Air Scandic, Air Scotland, Air Southwest, Air Sylhet, Air Transport Charter, AirUK, Air UK Leisure, Air Ulster, Air Wales, Aircraft Transport and Travel, Airflight, Airspan Travel, Airtours, Airfreight Express, Airways International, Airwork Limited, Airworld Alderney, Air Ferries, Alidair, All Cargo, All Leisure, Allied Airways, Alpha One Airways, Ambassador Airways, Amber Airways, Amberair, Anglo Cargo, Aquila Airways, -

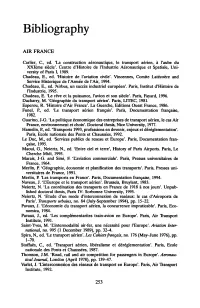

Bibliography

Bibliography AIR FRANCE Carlier, c., ed. 'La construction aeronautique, Ie transport aenen, a I'aube du XXIeme siecle'. Centre d'Histoire de l'Industrie Aeronautique et Spatiale, Uni versity of Paris I, 1989. Chadeau, E., ed. 'Histoire de I'aviation civile'. Vincennes, Comite Latecoere and Service Historique de l'Annee de l'Air, 1994. Chadeau, E., ed. 'Airbus, un succes industriel europeen'. Paris, Institut d'Histoire de l'Industrie, 1995. Chadeau, E. 'Le reve et la puissance, I'avion et son siecle'. Paris, Fayard, 1996. Dacharry, M. 'Geographie du transport aerien'. Paris, LITEC, 1981. Esperou, R. 'Histoire d'Air France'. La Guerche, Editions Ouest France, 1986. Funel, P., ed. 'Le transport aerien fran~ais'. Paris, Documentation fran~aise, 1982. Guarino, J-G. 'La politique economique des entreprises de transport aerien, Ie cas Air France, environnement et choix'. Doctoral thesis, Nice University, 1977. Hamelin, P., ed. 'Transports 1993, professions en devenir, enjeux et dereglementation'. Paris, Ecole nationale des Ponts et Chaussees, 1992. Le Due, M., ed. 'Services publics de reseau et Europe'. Paris, Documentation fran ~ise, 1995. Maoui, G., Neiertz, N., ed. 'Entre ciel et terre', History of Paris Airports. Paris, Le Cherche Midi, 1995. Marais, J-G. and Simi, R 'Caviation commerciale'. Paris, Presses universitaires de France, 1964. Merlin, P. 'Geographie, economie et planification des transports'. Paris, Presses uni- versitaires de France, 1991. Merlin, P. 'Les transports en France'. Paris, Documentation fran~aise, 1994. Naveau, J. 'CEurope et Ie transport aerien'. Brussels, Bruylant, 1983. Neiertz, N. 'La coordination des transports en France de 1918 a nos jours'. Unpub lished doctoral thesis, Paris IV- Sorbonne University, 1995. -

Hms Eagle 1964-1966

849D FLIGHT THINK we all shared a feeling of apprehension when 849 D Flight gathered in the hangar at Culdrose for I the commissioning ceremony on September 3rd 1964. Although there had been a D Flight in the past, we were a brand new Flight and many of us were comparatively new to the Gannet. But our detachment to Lossiemouth for Exercise TEAMWORK later that month soon put an end to any feelings of being new to the job. It seemed as if the aircraft resented being taken from their natural habitat of Cornwall to the windswept wastes of northern Scotland. They certainly put up a good fight. Remember Bernie Taft doing his nut every time another starter broke up, and P.O. Perks giving a performance of flame throwing during an engine run? By the time we got back to Culdrose, it seemed as if each aircraft had been taken to pieces and put together again - some of them more than once. These early days seemed to be full of embarkations and disembarkations. We'd hardly been aboard EAGLE a month before we disembarked to Seletar for our first taste of operational work: flying patrols up and down the Malacca Straits at dead f night. To remind the RAF that the Navy doesn't stop work just because it's four o'clock on a Sunday morning, we took to lighting up the second engine overhead the officers' mess when we returned after a patrol. There were the lighter moments of course - like the ti me `Dragon Leader' and his loyal officers were caught in the glare of the swimming pool arc lights at Seletar while having a midnight swim - negative trunks. -

Communications Department External Information Services 16 May 2018

Communications Department External Information Services 16 May 2018 Reference: F0003681 Dear I am writing in respect of your amended request of 17 April 2018, for the release of information held by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). You requested data on Air Operator Certificate (AOC) holders, specifically a complete list of AOC numbers and the name of the company to which they were issued. Having considered your request in line with the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA), we are able to provide the information attached. The list includes all the AOC holder details we still hold. While it does include some historical information it is not a complete historical list, and the name of the AOC holder is not necessarily the name of the organisation at the time the AOC was issued. If you are not satisfied with how we have dealt with your request in the first instance you should approach the CAA in writing at:- Caroline Chalk Head of External Information Services Civil Aviation Authority Aviation House Gatwick Airport South Gatwick RH6 0YR [email protected] The CAA has a formal internal review process for dealing with appeals or complaints in connection with Freedom of Information requests. The key steps in this process are set in the attachment. Civil Aviation Authority Aviation House Gatwick Airport South Gatwick RH6 0YR. www.caa.co.uk Telephone: 01293 768512. [email protected] Page 2 Should you remain dissatisfied with the outcome you have a right under Section 50 of the FOIA to appeal against the decision by contacting the Information Commissioner at:- Information Commissioner’s Office FOI/EIR Complaints Resolution Wycliffe House Water Lane Wilmslow SK9 5AF https://ico.org.uk/concerns/ If you wish to request further information from the CAA, please use the form on the CAA website at http://publicapps.caa.co.uk/modalapplication.aspx?appid=24. -

LONDON CITY AIRPORT 30 Years Serving the Capital 30 YEARS of SERVING LONDON 14 Mins to Canary Wharf 22 Mins to Bank 25 Mins to Westminster

LONDON CITY AIRPORT 30 years serving the capital 30 YEARS OF SERVING LONDON 14 mins to Canary Wharf 22 mins to Bank 25 mins to Westminster • Voted Best Regional Airport in the world* • Only 20 mins from terminal entrance to departure lounge • On arrival, just 15 minutes from plane to train LONDON CITY AIRPORT 30 years serving the capital Malcolm Ginsberg FAST, PUNCTUAL AND ACTUALLY IN LONDON. For timetables and bookings visit: *CAPA Regional Airport of the Year Award - 27/10/2016 londoncityairport.com 00814_30th Anniversary Book_2x 177x240_Tower Bridge.indd 1 26/06/2017 13:22 A Very Big Thank You My most sincere gratitude to Sharon Ross for her major contribution to the editorial and Alan Lathan, once of Jeppesen Airway Manuals, for his knowledge of the industry and diligence in proofing this tome. This list is far Contents from complete but these are some of the people whose reminiscences and memories have helped me compile a book that is, I hope, a true reflection of a remarkable achievement. London City Airport – LCY to its friends and the travelling public – is a great success, and for London too. My grateful thanks go to all the contributors to this book, and in particular the following: Andrew Scott and Liam McKay of London City Airport; and the retiring Chief Foreword by Sir Terry Morgan CBE, Chairman of London City Airport 7 Executive Declan Collier, without whose support the project would never have got off the ground. Now and Then 8 Tom Appleton Ex-de Havilland Canada Sir Philip Beck Ex-John Mowlem & Co Plc (Chairman) Introduction -

Fact Sheet Listing All the Aircraft Featured, in the Order of Their First Appearance

Classic Airliner Collection No.1 To support the commentary on this DVD, AVION VIDEO has produced this complimentary Fact Sheet listing all the aircraft featured, in the order of their first appearance. PLEASE RETURN THE SLIP BELOW TO RECEIVE A FREE CATALOGUE JRAF Argosy C. Mk1 XN853 Cunard Eagle Airways 707-465 VR-BBW RAF Argosy C. Mk1 XN852 British Eagle Britannia 305 G-ANCG RAF Argosy C. Mk1 XN854 British Eagle Viscount 700 RAF Argosy C. Mk1 XN855 British Eagle Britannia 300 Euravia Constellation British Eagle Viscount 732 G-ANRS Lufthansa L1049G D-ALEM British Eagle Britannia 312 G-AOVH Aer Lingus Carvair EI-AWR British Eagle Britannia 300 Aer Lingus Viscount 808 EI-AKL British Eagle Britannia 300 Aer Lingus F27-100 British Eagle Britannia 312 G-AOVM Sabena DC6B OO-SDQ British Eagle Britannia 312 Channel Airways DC3 G-AHCV British Eagle Britannia 312 G-AOVG Tunis Air DC4 British Eagle DC4 British United Viscount 800 British Eagle DC4 Dan Air Ambassador British Eagle 1-11 301AG G-ATPL SAM DC6B British Eagle 1-11 301AG G-ATPJ Caledonian DC7C British Eagle 1-11 301AG G-ATPL Dan Air Bristol Freighter British Eagle 1-11 301AG G-ATPL UTA DC6B British Eagle 1-11 207AJ G-ATTP BUAF Bristol Freighter British Eagle Britannia 305 G-ANCG Dan Air Ambassador *Middle East Airlines 707-365C VR-BCP Comair DC3 ZS-FRM British Eagle 1-11 304AX G-ATPH Prinair Riley Heron N586PR British Eagle Britannia 305 G-ANCF Prinair Riley Heron N564PR British Eagle 1-11-300 Prinair Riley Heron N568PR British Eagle Britannia 324 G-ARKB SAFE Air Bristol Freighter ZK-CRM -

The Anti-Deprivation Rule in Practice

Perpetually perplexing - the anti-deprivation rule in practice If Lord Neuberger MR admits that his judgment does not leave the law in a clear state, how are the rest of us to deal with it? Paul French, Guildhall Chambers Introduction 1. Despite its rather older roots1, the anti-deprivation rule first came to real prominence in the controversial decision2 of the House of Lords in British Eagle International Airlines Ltd v. Compagnie Nationale Air France [1975] 1 WLR 758. Its ambit and scope has recently been limited by a Court of Appeal decision in two cases, heard together, namely Perpetual Trustee Company Limited v. BNY Corporate Trustee Services Ltd3 (“Perpetual”) and Butters v. BBC Worldwide Ltd4 (“Butters”), together published at [2009] EWCA Civ 1160. 2. Perpetual concerned a structured finance transaction, which provided that the order of priority of distribution of the proceeds of realisation of collateral changes following an event of default under a swap agreement would flip if the defaulting party was the swap counterparty. Before default, the swap counterparty ranked first, but after default, it was the noteholders who had priority. In Butters, BBC granted Woolworths a licence to produce videos and DVDs of BBC television programmes. The joint venture agreement provided that upon the occurrence of a insolvency event, notice could be served requiring the other party to sell its shares at market value and also that such an event would cause the automatic termination of the licence. 3. In Each case the Court of Appeal was called upon to determine to what extent, if any, the anti-deprivation rule rendered the contractual provisions void. -

“The Migrant Caper”

Last updated 12.6.14 “The Migrant Caper” European migrant flights to Australia by charter operators 1947-1949 Compiled by Geoff Goodall The beginning: the first aircraft to carry migrants from Europe to Australia was Intercontinental Air Tours Lockheed Hudson VH-ASV Aurora Australis, parked at Camden NSW in 1947. Photo: Ed Coates collection By 1949 overseas operators with larger aircraft joined in the Australian migrant charters. Skyways International Curtiss C-46 Commando NC1648M is seen loading migrant passengers at Singapore after a refuelling stop en route from Europe to Australia. Photo via Robert Wiseman 1 “The Migrant Caper” - Contents Page Chapter 1 Introduction 3 Setting the scene 7 The Darker Side 8 DCA strikes back 10 The end of the migrant charters 12 The Operators – Australian 47 The Operators – USA 51 The Operators – International 58 Recorded Migrant Flight Movements 1947-49: SYDNEY 61 Recorded Migrant Flight Movements 1947-49: DARWIN 62 The Burma Connection 63 The Israeli Connection 71 Miscellanous Notes from the Period 72 Later Migrant flights to Australia 1950s-60s 73 The Players 102 References The title of this research paper The Migrant Caper comes from a chapter title in participating pilot Warren Penny’s unpublished autobiography. It summarizes, in the idiom of the day, the attitude of the former wartime pilots involved in this adventurous early post-war long-distance venture. An extraordinary chapter of Australia’s civil aviation history, which has gone largely unrecorded, is the early post World War Two period of ad-hoc charter flights carrying migrants from Europe to Australia. It began in 1947 with a handful of flights by Australian charter companies, flying mostly civilianised ex RAAF transports and bombers purchased from military disposals. -

The Silchester Eagle

Symbols of power: the Silchester bronze eagle and eagles in Roman Britain Article Accepted Version Durham, E. (2013) Symbols of power: the Silchester bronze eagle and eagles in Roman Britain. Archaeological Journal, 170 (1). pp. 78-105. ISSN 0066-5983 doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00665983.2013.11021002 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/39195/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00665983.2013.11021002 Publisher: Royal Archaeological Institute All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Author's Original Manuscript - Postprint This is an Author's Accepted Manuscript of an article published as: Durham, E. 2014. ‘Symbols of power: the Silchester bronze eagle and eagles in Roman Britain’, Archaeological Journal 170 (2013), 78–105 Routledge (Taylor & Francis), available online at: http://www.tandfonline.com/toc/raij20/current#.VKKuR14gAA. Symbols of power: the Silchester bronze eagle and eagles in Roman Britain Emma Durham with a contribution by Michael Fulford Those who study Roman art and religion in Britain will know that there are a relatively small number of pieces in stone and bronze which are regularly used to illustrate arguments on Romanization, provincialism and identity. -

The Flight of the Accountant: a Romance of Air and Credit

The Flight of The Accountant: a Romance of Air and Credit by Peter Armstrong (BSc Aeronautical Engineering) Contact Details Professor Peter Armstrong The Management Centre University of Leicester LE1 7RH e-mail [email protected] Abstract 2 Introduction When the first flight of the Aviation Traders Accountant became imminent we were very pleased to be able to go along to Southend Airport and take part in the occasion, for such it certainly was with many of the company’s workpeople out on the airfield to see their very first design take the air. Indeed a number of these found convenient extempore aeronautical grandstands on the dozens of ex- R.A.F. Prentices dotted about the airfield prior to their refurbishing as civil aeroplanes. Although the weather was unsettled, the plans went ahead smoothly and after the chief test pilot, Mr L.P. Stuart-Smith and the chief of flight tests, Mr D. Turner B.Sc. (Hons), had climbed aboard, the two Rolls-Royce Darts were started up with a shrill whine and the square-tipped Rotol propellers bit the air purposefully. The Accountant then taxied sedately to the end of the runway and turned into the wind, tension in the watching crowd mounting awhile. For several long moments the plump, silver partridge sat glistening and tranquil before the engines were opened up with a roar and the wheel brakes released. Trundling along at first, the Accountant rapidly gained speed and soon lifted well clear, retracting its wheels almost as soon as it was properly airborne. Flying smoothly and steadily, it climbed away with the Darts in full song and in no time was a small shape in the distance. -

Issue No. 341 Repo~T No. 271, August 1, 1975

Issue No. 341 Repo~t No. 271, August 1, 1975 ll page Community: Parliamentary Powers; Court of Auditors ••.• l Some Progress Reported at 'Routine Sununit' •••••••••••• 2 Mixed Reactions to Customs Union Resolution ••••••••••• 3 Britain: Withholding of 'Phantom Bill' Criticized ••••• 3 Netherlands: Controls on Lending; Minimum Capital ••••. 4 Italy: Liechtenstein Companies Lose Legal Status •••••• S Germany: EDP Storage of Legal Texts, Judgments? ••••••• 6 Euro Company Scene ....•...........•...•.•.......•..... 7 The Council of Ministers wound up its last meeting prior to the sununer recess by taking a concrete step in the direc ers; Court tion of increasing the European Parliament's budgetary pow Aµditors ers and by establishing a new Conununity institution, the Court of Auditors. Representatives of the nine govern ments signed the pertinent amendments to the three Euro pean treaties on July 22, thus clearing the way for ratification by the national legislatures. Enactment of the proposed amendments would empower the European Parliament to reject, for example, the Draft Budget as a whole by a majority of its members and two thirds of the votes cast. The future will tell whether the parliament will actually use this power or whether the authorization will remain largely symbolic. It is more likely that the assembly will occasionally insist on budg et changes within the limits set by total draft expendi tures. The Council could overrule parliament only by unanimous vote. Where the parliament proposes an increase in spending, a simple majority in the Council would suf fice for rejection. Establishment of the Court of Auditors would fulfill long-standing demands from many factions in the EC, since it would permit audits of Conununity expenditures and reve nues.