An Examination and Theorisation of Consumer-Brand Relationship and Its Link to Customer-Based Brand Equity By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Head CG··

ews Vol. LIV WELLESLEYCOLLEGE NEWS, WELLESLEY,MASS., FEBRUARY23, 1961 No. 15 Healey Asks Revision of Rules Marcia Burick InLI:;:::::t~P~~~t~~{;:~~;;J~To Head CG·· • • f NATO asking more than he is willing to ac- Marcia Burick '62 has been elected 0 fl P 0Slll0Il O cept, maintaining that in the political President of College Government. The old game of power politics is Russia has less control ov r the arena "it is better to be right sepa- Announcement was made at run- open to suggestions from the floor Communist world than he had fu- rately than wrong together." On mat- arounds afte1 Chapel Monday. Mar- for revision. teen year ago. ters outside NATO's jurisdiction, the cia will take office after Spring va- Western allies have no obligation to cation. In June, 1955 West Germany was "New Floating Vote" the scene of atomic war games in Fourth, Healy noted that Asia and support each other. Marcia, who believes that C. G. which, according to official estimates, Africa, no longer under colonial rule, "There is no more reason why should be "a sounding board for 1,7000,000 were killed and 3,500,000 have become a "floating vote." He America should support European ideas as well as a legislative body". wounded. The U. S. was not "in• warned that a local eruption in either countries on colonial issues than why has some specific immediate plan vaded." of these areas could involve the U. S. Europe shoulld support America on She hopes to have senior CG officers By such "war games" Denis Healey, or U.S.S.R. -

Brand Loyalty Reloaded

RED P APER BR AND LOYALT Y RELOADED 2015 KEVIN ROBERTS EXECUTIVE CHAIRMAN ABSTRACT This is a “red” rather than “white” paper because Saatchi & Saatchi operates from the edges, zigs when others zag. Red is the color of passion, hope and optimism. Red is the color of spirit, the root word of inspiration. This paper is a discursive view of brand loyalty as it applies to the marketing imperatives of 2015. For a CEO, brand loyalty is the ultimate business deliverer, a f low state, but the hardest to achieve; more alchemy than science. Beyond Reason. This paper surveys recent literature about loyalty framed by our Lovemarks philosophy regarding the future beyond brands, but more particularly, it proposes that mastering the emotional dimensions of marketing is by far the most important requisite of an enterprising life in business. AUTHOR Kevin Roberts is New York-based Executive Chairman of Saatchi & Saatchi and Head Coach of Publicis Groupe, the world’s third largest communications group. Saatchi & Saatchi is one of the world’s leading creative organizations with 6500 people and 130 offices in 70 countries and works with six of the top 10 and over half of the top 50 global advertisers. Kevin Roberts started his career in the late 1960s as a brand manager with iconic London fashion house Mary Quant. He became a senior marketing executive for Gillette and Procter & Gamble in Europe and the Middle East. At 32, he became CEO of Pepsi-Cola Middle East; and later Pepsi’s CEO in Canada. In 1989, Roberts moved with his family to Auckland, New Zealand, to become Chief Operating Officer with Lion Nathan. -

PIAGGIO WIDE 13 ULTIMO:Layout 1

Quarterly magazine Year 17 June 2010 Intervista al Presidente Il nuovo Vietnam di Nguyen Minh Triet (Interview to the President The new Vietnam of Nguyen Minh Triet) SHANGHAI: PIAGGIO MP3 ASIAASIA SBARCA IN CINA (Chinese debut for the Piaggio MP3) 20102010 ASIA CHIAMA EUROPA: PARLA VogliaVoglia L’ECONOMISTA LI-GANG LIU d’Italiad’Italia (Asia calls Europe: we talk Wide Piaggio Magazine, Registrazione al Tribunale di Pisa n. 5 del 15/05/1993. Anno 17 – N. 2 Giugno 2010 – Contiene I.P. Anno 17 – N. di Pisa n. 5 del 15/05/1993. Tribunale al Piaggio Magazine, Registrazione Wide to economist Li-Gang Liu) (A passion for Italy) Bend to the curves, stand up to adversity. The true bikers are back. Griso 8V Certain feelings can never be forgotten. They lie silent somewhere deep in your soul, ready to be aroused. This moment has arrived: pride has returned, the true bikers are back. We will reclaim the road and the pleasure of riding free. The Moto Guzzi dealers are awaiting to relight your fire. WWW.MOTOGUZZI.IT Giugno/June SOMMARIO/CONTENTS 2010 WIDE Piaggio Magazine Quarterly magazine published by Piaggio & C. S.p.A. Magazine Trimestrale edito da Piaggio & C. S.p.A. 004 010 Registrazione del Tribunale di Pisa n. 5 del 15/05/1993 - Anno 17 – N. 2 Giugno 2010 Editor Direttore Responsabile Francesco Fabrizio Delzìo Steering Committee Comitato Editoriale Michele Pallottini, Maurizio Roman, Ravi Chopra, Carlo Coppola, Massimo Di Silverio, Franco Fenoglio, Luciana Franciosi, Giancarlo Milianti, Pedro Quijada, Costantino Sambuy, Stefano Sterpone, Paolo Timoni, Gabriele Galli, Leo Francesco Mercanti, Roberto M. -

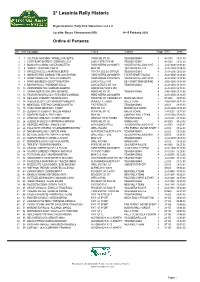

Classifiche Rally

2° Lessinia Rally Historic Organizzazione: Rally Club Valpantena ssd a rl Localita: Bosco Chiesanuova (VR) 14-15 Febbario 2020 Ordine di Partenza Ord.Num.Equipaggio Vettura Scuderia RaggrGr/Cl Orario 1 1 VOLTOLINI MASSIMO / MORELLI GIUSEPPE PORSCHE 911 SC TEAM BASSANO 3 4/>2000 09:01:00 2 2 COSTENARO GIORGIO / ZAMBIASI LUCIA LANCIA STRATOS HF TEAM BASSANO 2 4/>2000 09:02:00 3 3 BIANCO RICCARDO / VALERIO MATTEO FORD SIERRA COSWORTH SCUDERIA PALLADIO HIST. 4 J2-A/>2000 09:03:00 4 4 "RAFFA" / SCARDONI PAOLO BMW M3 SCALIGERA RALLYE 4 J2-A/>200009:04:00 5 5 PATUZZO NICOLA / MARTINI ALBERTO TOYOTA CELICA GTFOUR TEAM BASSANO 4 J2-A/>200009:05:00 6 6 BARSANTI PIER GIORGIO / POLLINI CRISTIAN FORD SIERRA COSWORTH EVENTI SPORT RACING 4 J2-A/>2000 09:06:00 7 7 ZANETTI PIERLUIGI / SCALCO ROBERTO FORD SIERRA COSWORTH SCUDERIA PALLADIO HIST. 4 J2-A/>2000 09:07:00 8 8 FINATI MAURIZIO / CODOTTO MARTINA LANCIA RALLY 037 KEY SPORT ENGINEERING 4 J1-B/>160009:08:00 9 9 BAGGIO PAOLO / PAGANONI GIULIA LANCIA DELTA INT. 16V TEAM BASSANO 4 J2-A/>200009:09:00 10 10 ZANINI MARIO IVO / CORRADI ALBERTO LANCIA DELTA HF 4 WD 4 J2-A/>200009:10:00 11 11 SANNA ALERTO / DAL BRA' ALFONSO PORSCHE 911 SC TEAM BASSANO 4 J1-B/>160009:11:00 12 12 PESAVENTO GIANLUCA / PESAVENTO GIORGIO FORD SIERRA COSWORTH 4 J2-A/>200009:12:00 13 14 DELLADIO LORENZO / MENGON LUCA PORSCHE 911 CARRERA RS MANGHEN TEAM 2 4/>2000 09:13:00 14 15 STERZA GUIDO / LUCCHI MAURO UMBERTO RENAULT 5 TURBO RALLY TEAM 4 J1-B/>160009:14:00 15 18 MENEGOLLI STEFANO / ZAMBELLI MATTIA FIAT RITMO 75 TEAM BASSANO 3 2/1600 09:15:00 16 19 VISINTAINER MAURIZIO / "FIORE" BMW M3 E30 MARANELLO CORSE 4 J2-A/>200009:16:00 17 20 ZERBINATO ALBERTO / BALLINI ANDREA PORSCHE 911 SC RAETIA CORSE 3 1-3/>2000 09:17:00 18 22 BOMBIERI NICOLA / TRIPI LINDA BMW M3 COMPANY RALLY TEAM 4 J2-A/>200009:18:00 19 23 ZANDONA' DAMIANO / STOPPA SIMONE RENAULT R5 GT TURBO TEAM BASSANO 4 J1-A/2000 09:19:00 20 24 GUGLIELMI GIULIO / CORRADINI GIORDANO PORSCHE 911 SC OMEGA ASD 3 4/>2000 09:20:00 21 25 REGAZZO ANTONIO / ANNONI LUIGI ALFA ROMEO GTV 6 SCUDERIA PALLADIO HIST. -

Richard's 21St Century Bicycl E 'The Best Guide to Bikes and Cycling Ever Book Published' Bike Events

Richard's 21st Century Bicycl e 'The best guide to bikes and cycling ever Book published' Bike Events RICHARD BALLANTINE This book is dedicated to Samuel Joseph Melville, hero. First published 1975 by Pan Books This revised and updated edition first published 2000 by Pan Books an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Ltd 25 Eccleston Place, London SW1W 9NF Basingstoke and Oxford Associated companies throughout the world www.macmillan.com ISBN 0 330 37717 5 Copyright © Richard Ballantine 1975, 1989, 2000 The right of Richard Ballantine to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. • All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. • Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Bath Press Ltd, Bath This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall nor, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

How Do Brands Become Partners for Life? Customer Brand Relationship (CBR)

How do brands become partners for life? Customer Brand Relationship (CBR) The issue of brand management and evaluation has become ever more important and essential for brand research over the last few decades. Companies use brand research to help evaluate WHERE in the purchasing decision- making process of the consumer (now referred to as the “consumer journey”) their brand is positioned and WHY. This knowledge is needed in order to manage brands in a targeted way in future. On the one hand, this means setting the brand apart from the competition, and on the other, meeting the ideals of consumers, convincing them to continue along the consumer journey. In light of this, it is not surprising that a number of approaches aim to explain why a brand has been successful in reaching consumers at a particular stage in the consumer journey, while others have not yet been able to progress further or are in a critical position. In short, what determines brand strength and the appeal of different brands in the market and therefore validates the position it assumes in the specific decision-making process? In this context, different emotional attitudes play a key role. The research approach for brand evaluation has been undergoing constant development for many years, often influenced by the latest scientific findings. Attempting to explain the WHERE was the starting point: purchasing intention is the typical basis for approaches to brand strength measurement. It is described as a mental state which reflects the intent of customers to buy a set volume of a specific brands goods over a particular period of time (Howard, 1994) or as a subjective prediction of future behavior (Blackwell/Minard/Engel, 2001). -

RESEARCH FINDINGS and FUTURE PRIORITIES Kevin Lane Keller

BRANDS AND BRANDING: RESEARCH FINDINGS AND FUTURE PRIORITIES Kevin Lane Keller Tuck School of Business Dartmouth College Hanover, NH 03755 (603) 646-0393 (o) (603) 646-1308 (f) [email protected] Donald R. Lehmann Graduate School of Business Columbia University 507 Uris Hall 3022 Broadway New York, NY 10027 (212) 854-3465 (o) (212) 854-8762 (f) [email protected] August 2004 Revised February 2005 Second Revision May 2005 Thanks to Kathleen Chattin from Intel Corporation and Darin Klein from Microsoft Corporation, members of the Marketing Science Institute Brands and Branding Steering Group, and participants at the Marketing Science Institute Research Generation Conference and 2004 AMA Doctoral Consortium for helpful feedback and suggestions. BRANDS AND BRANDING: RESEARCH FINDINGS AND FUTURE PRIORITIES ABSTRACT Branding has emerged as a top management priority in the last decade due to the growing realization that brands are one of the most valuable intangible assets that firms have. Driven in part by this intense industry interest, academic researchers have explored a number of different brand-related topics in recent years, generating scores of papers, articles, research reports, and books. This paper identifies some of the influential work in the branding area, highlighting what has been learned from an academic perspective on important topics such as brand positioning, brand integration, brand equity measurement, brand growth, and brand management. The paper also outlines some gaps that exist in the research of branding and brand equity and formulates a series of related research questions. Choice modeling implications of the branding concept and the challenges of incorporating main and interaction effects of branding as well as the impact of competition are discussed. -

Annual Report & Accounts 2019

ANNUAL REPORT & ACCOUNTS 2019 SPORTS DIRECT INTERNATIONAL PLC AT A GLANCE Founded as a single store in 1982, Sports Direct International plc (Sports Direct, the Group, the Business or the Company) is today the UK’s largest sporting goods retailer by revenue. The Group operates a diversified portfolio of sports, fitness, fashion and lifestyle fascias in over 20 countries. We have approx. 29,400 staff across six business segments: UK Sports Retail, Premium Lifestyle, House of Fraser Retail, European Sports Retail, Rest of World Retail and Wholesale & Licensing. Our business strategy is to invest in our people, our business, and our key third party brand partners, in order to elevate our retail proposition across all our channels to attain new levels of excellence. The Group aspires to be an international leader in sports, lifestyle, and luxury apparel retail, by offering our customers a dynamic range of iconic brands. We value our people, our customers, our shareholders and our third-party brand partners - and we strive to adopt good practices in all our corporate dealings. We are committed to treating all people with dignity and respect. We endeavour to offer customers an innovative and unrivalled retail experience. We aim to deliver shareholder value over the medium to long-term, whilst adopting accounting principles that are conservative, consistent and simple. MISSION STATEMENT ‘TO BECOME EUROPE’S LEADING ELEVATED SPORTING GOODS RETAILER.’ CONTENTS 1 HIGHLIGHTS AND OVERVIEW 002 2 STRATEGIC REPORT Chair’s Statement ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Prospetto Informativo

PROSPETTO INFORMATIVO relativo all’Offerta Pubblica di Vendita e all’ammissione a quotazione sul Mercato Telematico Azionario organizzato e gestito da Borsa Italiana S.p.A. delle azioni ordinarie di 26MAY200619560790 Azionisti Venditori Piaggio Holding Netherlands B.V. Scooter Holding 1 S.r.l. Responsabile del Collocamento per l’Offerta Pubblica di Vendita e Sponsor Mediobanca – Banca di Credito Finanziario S.p.A. Responsabile del Collocamento per l’Offerta Pubblica di Vendita Banca Caboto S.p.A. (Gruppo Intesa) Coordinatori dell’Offerta Pubblica Globale di Vendita Banca Caboto S.p.A. (Gruppo Intesa) – Citigroup Global Markets Limited – Deutsche Bank – Lehman Brothers International (Europe) – Mediobanca – Banca di Credito Finanziario S.p.A. L’OFFERTA PUBBLICA GLOBALE DI VENDITA COMPRENDE UN’OFFERTA PUBBLICA DI VENDITA RIVOLTA AL PUBBLICO INDISTINTO IN ITALIA, EUN COLLOCAMENTO ISTITUZIONALE RISERVATO AD INVESTITORI PROFESSIONALI IN ITALIA E A INVESTITORI ISTITUZIONALI ALL’ESTERO AI SENSI DELLA REGULATION S DELLO UNITED STATES SECURITIES ACT DEL 1933 COME SUCCESSIVAMENTE MODIFICATO, CON ESCLUSIONE DEGLI INVESTITORI ISTITUZIONALI DELL’AUSTRALIA, CANADA E GIAPPONE E AD INCLUSIONE DEGLI STATI UNITI D’AMERICA AI SENSI DELLA RULE 144A ADOTTATA IN FORZA DELLO UNITED STATES SECURITIES ACT DEL 1933. UNA QUOTA DELL’OFFERTA PUBBLICA DI VENDITA E` RISERVATA AI DIPENDENTI DI PIAGGIO & C. S.P.A. E DELLE SOCIETA` DA ESSA CONTROLLATE. PROSPETTO INFORMATIVO DEPOSITATO PRESSO LA CONSOB IN DATA 16 GIUGNO 2006 A SEGUITO DI COMUNICAZIONE DELL’AVVENUTO RILASCIO DEL NULLA OSTA DELLA CONSOB, CON NOTA DEL 15 GIUGNO 2006 PROTOCOLLO N. 6052651. L’ADEMPIMENTO DI PUBBLICAZIONE DEL PROSPETTO INFORMATIVO NON COMPORTA ALCUN GIUDIZIO DELLA CONSOB SULL’OPPORTUNITA` DELL’INVESTIMENTO PROPOSTO E SUL MERITO DEI DATI E DELLE NOTIZIE ALLO STESSO RELATIVI. -

Classifica Finale

XVIII CITTA' DI LUMEZZANE COPPA D'ORO AVIS E COPPA PAM LUMEZZANE ( BS ) 9 SETTEMBRE 2018 LUMEZZANE ( BS ) - 09/09/2018 Classifica Finale Pos No Pilota Copilota Vettura / Squadra Gr/Cl Pilota Top Punti Autobianchi A11 1 27 R. Boracco (ITA) A. Bossi (ITA) -/8 TOP 143 Abarth/ Lancia 2 23 S. Pasinato (ITA) D. Piga (ITA) Fulvia/Nettuno -/6 TOP 149 Bologna Fiat Balilla 3 7 A. Riboldi (ITA) P. Sabbadini (ITA) 508S/Franciacorta -/1 TOP 154 Motori Autobianchi A112 4 24 M. Zanasi (ITA) B. Bertini (ITA) -/7 TOP 159 Elite/Classic Team Fiat 508 S 5 6 L. Turelli (ITA) M. Turelli (ITA) Sport/Franciacorta -/1 TOP 163 Motori Alfa Romeo 6C 1750 6 2 A. Vesco (ITA) A. Guerini (ITA) -/1 TOP 164 SS Zagato/ Fiat 508 S/Loro 7 5 A. Belometti (ITA) D. Vavassori (ITA) -/1 TOP 165 Piana Fiat 508 8 9 E. Bellini (ITA) R. Tiberti (ITA) C/Franciacorta -/1 TOP 165 Motori 9 14 M. Cibaldi (ITA) A. Costa (ITA) Fiat Gilco/ -/2 TOP 172 Leyland Mini 10 22 T. Baldissera (ITA) E. Covaz (ITA) Cooper/Nettuno -/6 TOP 176 Bologna Autobianchi 11 21 A. Fontana (ITA) S. Grossi (ITA) -/6 TOP 179 A112/Classic Team Autobianchi 12 25 M. Dalleolle (ITA) A. Traversi (ITA) A112/Nettuno -/7 TOP 186 Bologna Fiat 508/C/Nettuno 13 11 A. Scapolo (ITA) G. Scapolo (ITA) -/1 TOP 195 Bologna 14 12 F. Spagnoli (ITA) G. Parisi (ITA) Fiat 508/Franciacorta -/1 TOP 198 Motori Alfa Romeo 2000 15 20 A. Bonetti (ITA) A. -

Footwear IP Digest Oct 2014

From: FDRA [email protected] Subject: Footwear IP Digest Oct. 2014 Date: January 12, 2015 at 2:18 PM To: [email protected] Having trouble viewing this email? Click here September 2014 Legislation There was no new legislation introduced. Litigation Adidas AG v. adidasAdipure11pro2.com, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 131706 (S.D. Fla. Sept. 18, 2014). Synopsis: A federal court grants Adidas and Reebok a final default judgment against dozens of websites purveying counterfeit Adidas and Reebok footwear, ordering a permanent injunction against the sites. Deckers Outdoor Corp. v. J. C. Penney Company Inc., 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 126266 (C.D. Cal. Sept. 8, 2014). Synopsis: A federal court grants JC Penney's motion to dismiss Deckers's claims for false designation of origin, willful patent infringement, and unfair competition but denies its motion to dismiss Deckers' claim that JC Penney infringed its UGG boot patent. Coach, Inc. v. 3D Designers Inspirations, 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 136933 (C.D. Ill. Sept. 29, 2014). Synopsis: A federal court grants Coach a default judgment against 3D Designers Inspirations, a small- scale retailer, for selling counterfeit Coach products, awarding Coach monetary and injunctive relief. Deckers Outdoor Corp. v. Ozwear Pty Ltd., 2014 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 132169 (C.D. Cal. Sept. 18, 2014). Synopsis: A federal court grants Deckers' a default judgment against Ozwear, an internet retailer based in Australia, for infringement of its UGG trademark and UGG boot patent, awarding Deckers statutory damages under the Lanham Act and a permanent injunction. USPTO Utility patents issued in the month of September: Utility patents issued in the month of September: Pat. -

Domenica 15 Ottobre 2017 Rassegna Del 15/10/2017

domenica 15 ottobre 2017 Rassegna del 15/10/2017 ... 15/10/2017 Corriere dello Sport 1 Prima pagina ... 1 15/10/2017 Corriere dello Sport 1 Prima pagina ... 2 Roma 15/10/2017 Gazzetta dello Sport 1 Prima pagina ... 3 15/10/2017 Tuttosport 1 Prima pagina ... 4 COMITATO ITALIANO PARALIMPICO 15/10/2017 Ciociaria Oggi 18 Inaugurato il complesso sportivo Cappuccini ... 5 15/10/2017 Corriere dello Sport 47 Tiro con l'arco. Da oggi Mondiali in Messico con Galiazzo & C. ... 6 15/10/2017 Giorno Monza Brianza 15 Stamattina dalle 9 via alla «5k ability run» e in piazza Trento il ... 7 Village Paralimpico 15/10/2017 La Verita' 8 A Milano vaccinarsi contro la meningite è impossibile Meucci Emanuela 8 14/10/2017 Messaggero Veneto 61 Un solo set perso: è oro Giada Rossi non si ferma Padovano Rosario 9 Udine 15/10/2017 Secolo XIX 45 Intervista ad Asia Giordano - Asia, tre medaglie e una promessa Arrichiello Valerio 10 15/10/2017 Stampa 26 Tv & Tv - Bebe Vio il suo sorriso non inganna Comazzi Alessandra 11 POLITICA SPORTIVA 15/10/2017 Corriere della Sera 21 Lotti e Malagò in campo Lo sport supera le barriere Fiorentino Flavia 12 15/10/2017 Gazzetta dello Sport 25 Non solo calcio - L'urlo» di Napoli contro Tardelli Narducci Fausto 13 15/10/2017 Sole 24 Ore 16 Sport&Business - Parte la SuperLega di volley maschile, 14 Giardina Benedetto 14 franchigie con il modello Nba 15/10/2017 Sole 24 Ore 16 S&b news - Img gestirà licenze e vendite fino a 2023 ..