An Analysis of the Impact of Industry Role Players on the Competitiveness and Profitability of an Entity in a Volatile Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

12 Nts Wild Valleys Plains

12 nts Wild Valleys & Plains - Exclusive 12 nights / 13 days Starts Lusaka, Zambia / Ends Harare, Zimbabwe From $9860 USD per person P/Bag 0178, Maun, Botswana Tel: +267 72311321 [email protected] Botswana is our home Safaris are our passion Day Location Accommodation Transfers / Activities Meals 1 Arcades, Lusaka Lusaka Protea Hotel Upon arrival at Lusaka Airport – eta TBA – you - (bed and Standard room are met and road transfer to Lusaka Protea breakfast) Hotel. Settle into Hotel, afternoon at leisure. 2 South Luangwa Chinzombo Camp After breakfast, road transfer from Lusaka B, L (flight National Park Luxury Villa Protea Hotel to Lusaka airport for the Pro-flight time flight to Mfuwe Airport where you are met and permitting) road transfer to Chinzombo Camp. Afternoon , D & SB activity 3 South Luangwa Chinzombo Camp Day of activities: guided walking Safaris and B, L, D & SB National Park game drives into Luangwa national park 4 Luangwa River Mchenja Bush Camp After breakfast and possible morning activity B, L, D & SB Luxury safari tent game drive or walking transfer to Mchenja. Afternoon activity. 5 Luangwa River Mchenja Bush Camp Day of activities from a choice of: guided B, L, D & SB walking safaris, day and night game drives. 6 Lower Zambezi Chongwe River Camp After breakfast and possible morning activity B, L, D & SB Classic Safari Tent (flight time permitting), road transfer to Mfuwe airport for Pro Flight air transfer to Royal airstrip. Here you are met and transfer to Chongwe River camp. Afternoon activity 7 Lower Zambezi Chongwe River Camp Day of activities: game drives, guided walks, B, L, D & SB canoeing and boating 8 Mana Pools Ruckomenchi Camp After breakfast and possible morning activity, B, L, D & SB National Park Classic Safari Tent (flight time permitting) road/boat transfer across the border into Zimbabwe to Ruckomenchi Camp. -

Introduction 3 Before Arrival in Arusha 3

Introduction 3 Before arrival in Arusha 3 Mail Address 3 Pre-Registration 3 Travel to and from Arusha 4 Insurance 5 Visa, Passports and Entry Formalities 5 Customs Formalities 8 th Welcome to the 47 Annual Health Services 8 Meeting of the Board Air Transport 9 of Governors of the African Development Bank and the Hotel Accommodation in Arusha 9 38th Annual Meeting of the Arrival in Arusha 11 Board of Governors of the Reception at Kilimanjaro International Airport 11 African Development Fund Annual Meetings Information 11 Press 11 28 May - 1 June 2012 Practical Information 12 Arusha Telecommunications 12 Tanzania The AICC Conference Facility 12 Practical Information 13 Car Rental Services in Arusha 15 Commercial Banks in Arusha 16 Places of Interest in Arusha 16 Shopping Centres 18 Places of Worship 19 Security 20 Badges 20 Annexes I 2012 Annual Meetings of the Boards of Governors of the African Development Bank Group 23 II Provisional Spouse Programme 26 III AfDB Board of Governors- Joint Reception and Gala Dinner Programme 27 IV Diplomatic Missions Accredited to Tanzania 28 V Tanzania Diplomatic Missions Abroad 37 VI Hotels in Arusha Description and Accommodation Booking 41 VII Airlines Serving Dar es Salaam (Julius Nyerere International Airport) 46 VIII Hospital and Special Assistance for emergencies in Arusha 47 IX Hospital and Special Assistance for emergencies in Arusha 48 X Emergency Call in Arusha 49 1 2 Introduction The 2012 Annual Meetings of the Boards of Governors of the African Development Bank Group (African Development Bank and the African Development Fund) will take place in Arusha, Tanzania, at the Arusha International Conference Centre (AICC), from 28May to 1 June 2012. -

Energy - GRZ Considers Setting up Biofuel Project

Share 0 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In Flavafm 87.7MHz Radio Blog Corporate Governance, Business and Economic News from the Copperbelt and Beyond S U N D A Y, M A Y 3 , 2 0 0 9 Corporat e ident it y Energy - GRZ Considers Setting up Biofuel Project LUSAKA - Government is considering setting up a multi-million Kwacha biofuel cultivation project with a Canadian company - Bedford Biofuel. List en t o Flavafm 87.7MHz Plays with WinAmp, Real Player Bedford Biofuel of Canada or itunes...Click here has declared interest in investing in jathropa Subscribe via email cultivation in Zambia, a project which Government hopes will bring in foreign exchange Enter your email address: and make Zambia an exporter of biofuel. Speaking during a meeting with Mr Mutati in Lusaka yesterday, Bedford president and chief executive officer, David Mcclure, Subscribe said if land was provided, the company would immediately go Delivered by FeedBurner into cultivation and create jobs for thousands of people. “If we get land in the next six months, we will plant faster than anyone else. If we plant on 150,000 hectares of land, we will give jobs to everyone in need,” Mr Mcclure said. He said theirs is a consortium of business partners and if given land in Zambia, Bedford Biofuels will bring in other partners that Subscribe To will be interested in the long-term benefit of the project. Posts Mr Mcclure said once they start harvesting, Bedford Biofuels is capable of producing a million litres of diesel in a day. He said Comments the project would not only create employment, but food security too, as jathropa fields are suitable for animal rearing. -

Prior Compliance List of Aircraft Operators Specifying the Administering Member State for Each Aircraft Operator – June 2014

Prior compliance list of aircraft operators specifying the administering Member State for each aircraft operator – June 2014 Inclusion in the prior compliance list allows aircraft operators to know which Member State will most likely be attributed to them as their administering Member State so they can get in contact with the competent authority of that Member State to discuss the requirements and the next steps. Due to a number of reasons, and especially because a number of aircraft operators use services of management companies, some of those operators have not been identified in the latest update of the EEA- wide list of aircraft operators adopted on 5 February 2014. The present version of the prior compliance list includes those aircraft operators, which have submitted their fleet lists between December 2013 and January 2014. BELGIUM CRCO Identification no. Operator Name State of the Operator 31102 ACT AIRLINES TURKEY 7649 AIRBORNE EXPRESS UNITED STATES 33612 ALLIED AIR LIMITED NIGERIA 29424 ASTRAL AVIATION LTD KENYA 31416 AVIA TRAFFIC COMPANY TAJIKISTAN 30020 AVIASTAR-TU CO. RUSSIAN FEDERATION 40259 BRAVO CARGO UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 908 BRUSSELS AIRLINES BELGIUM 25996 CAIRO AVIATION EGYPT 4369 CAL CARGO AIRLINES ISRAEL 29517 CAPITAL AVTN SRVCS NETHERLANDS 39758 CHALLENGER AERO PHILIPPINES f11336 CORPORATE WINGS LLC UNITED STATES 32909 CRESAIR INC UNITED STATES 32432 EGYPTAIR CARGO EGYPT f12977 EXCELLENT INVESTMENT UNITED STATES LLC 32486 FAYARD ENTERPRISES UNITED STATES f11102 FedEx Express Corporate UNITED STATES Aviation 13457 Flying -

Hospitals Conducting in Zambia

HOSPITALS CONDUCTING COVID-19 PCR TESTS IN ZAMBIA A. LUSAKA Medland Hospital Plot 9 Mukonteka Close Rhodespark Tel: +260 761 101 600 Email: [email protected] CIDRZ Central Laboratory Kalingalinga District Clinic Off Alick Nkhata Road Kalingalinga, Lusaka Tel: +260 975 138 102 Email: [email protected] REQUENTLY Victoria Hospital 5498 Lunsemfwa Road Kalundu, Lusaka. Tel: +260 962 727 2904 SKED Coptic Hospital Lusaka Zambia Plot 11304 Manchinchi Rd Tel: +260962202295 UESTIONS Forest Park INTERNATIONAL TRAVELERS Plot 8238 Nangwenya Tel: +260-211-254819/+260 973183338 Email: [email protected] check with your carrier B. LIVINGSTONE COVID-19 for COVID-19 travel requirements as they Livingstone General Hospital may be different Akapelwa Street, Tel: +260 213 320 221 ?? COVID-19 Where can I get tested for Q6 COVID-19? ANS: PCR tests are available at all Government Provincial REQUENTLY Hospitals in urban centres such as Lusaka, Livingstone and Ndola. The tests are also available from private SKED hospitals, see attached list with details. The service is available at a fee. UESTIONS Do I need a Medical Travel Q7 Certificate when returning to my country after visiting INTERNATIONAL TRAVELERS Zambia? ANS: You may, depending Zambia has been endorsed with a Do I need to have a COVID-19 Negative Test safety stamp by the World Travel on the requirements by either Q1 Certificate when I travel to Zambia? and Tourism Council (WTTC) for the airlines or destination of ANS: Yes, a SARS CoV2 PCR Test international travel disembarkation, check the details before departure for your convenience. How long should the Negative COVID-19 PCR Will I be Quarantined upon arrival Q2 Test be valid for? Q4 into Zambia? Does the tourism sector in ANS: 72 Hours. -

Fact Finding Airports Southern Africa

2015 FACT FINDING SOUTHERN AFRICA Advancing your Aerospace and Airport Business FACT FINDING SOUTHERN AFRICA SUMMARY GENERAL Africa is home to seven of the world’s top 10 growing economies in 2015. According to UN estimates, the region’s GDP is expected to grow 30 percent in the next five years. And in the next 35 years, the continent will account for more than half of the world’s population growth. It is obvious that the potential in Africa is substantial. However, African economies are still to unlock their potential. The aviation sector in Africa faces restrictive air traffic regimes preventing the continent from using major economic benefits. Aviation is vital for the progress in Africa. It provides 6,9 million jobs and US$ 80 million in GDP with huge potential to increase. Many African governments have therefore, made infrastructure developments in general and airport related investments in particular as one of their priorities to facilitate future growth for their respective country and continent as a whole. Investment is underway across a number of African airports, as the region works to provide the necessary infrastructure to support the continent’s growth ambitions. South Africa is home to most of the airports handling 1+ million passengers in Southern Africa. According to international data 4 out of 8 of those airports are within South African Territory. TOP 10 AIRPORTS [2014] - AFRICA CITY JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA 19 CAIRO, EGYPT 15 CAPE TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA 9 CASABLANCA, MOROCCO 8 LAGOS, NIGERIA 7,5 HURGHADA, EGYPT 7,2 ADDIS -

Airlines List in Outside

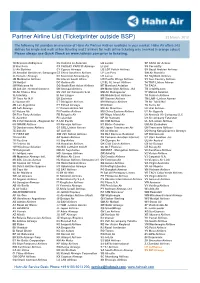

Partner Airline List (Ticketprinter outside BSP) 23 March, 2012 The following list provides an overview of Hahn Air Partner Airlines available in your market. Hahn Air offers 243 airlines for single and multi airline ticketing and 2 airlines for multi airline ticketing only (marked in orange colour). Please always use Quick Check on www.hahnair.com prior to ticketing. 1X Branson AirExpress CU Cubana de Aviacion LG Luxair SP SATA Air Acores 2I Star Perú CX CATHAY PACIFIC Airways LI Liat SS Corsairfly 2J Air Burkina CY Cyprus Airways LO LOT Polish Airlines SV Saudi Arabian Airlines 2K AeroGal Aerolineas Galapagos CZ China Southern Airlines LP Lan Peru SW Air Namibia 2L Helvetic Airways D2 Severstal Aircompany LR Lacsa SX SkyWork Airlines 2M Moldavian Airlines D6 Interair South Africa LW Pacific Wings Airlines SY Sun Country Airlines 2N Nextjet DC Golden Air LY EL AL Israel Airlines T4 TRIP Linhas Aéreas 2W Welcome Air DG South East Asian Airlines M7 Marsland Aviation TA TACA 3B Job Air - Central Connect DN Senegal Airlines M9 Motor Sich Airlines JSC TB Jetairfly.com 3E Air Choice One DV JSC Air Company Scat MD Air Madagascar TF Malmö Aviation 3L InterSky EI Aer Lingus ME Middle East Airlines TK Turkish Airlines 3P Tiara Air N.V. EK Emirates MF Xiamen Airlines TM LAM - Linhas Aereas 4J Somon Air ET Ethiopian Airlines MH Malaysia Airlines TN Air Tahiti Nui 4M Lan Argentina EY Etihad Airways MI SilkAir TU Tunis Air 4Q Safi Airways F7 Darwin Airline SA MK Air Mauritius U6 Ural Airlines 5C Nature Air F9 Frontier Airlines MU China Eastern Airlines -

Annual Report Annual

LINES A IR SSO A MPAGNIES AER CO IEN C N ES N I A D ES A N A T C IO F I T R I I O R IA C C A F I N O N S E A S S A AFRAA getperformancemore Africaines Aériennes Compagnies Association des AIRLINES ASSOCIATION 2012 ANNUAL REPORT AFRICAN 2012 ANNUAL REPORT The Q400 NextGen gives Ethiopian Airlines the low operating costs and superior performance they need to increase productivity. Ethiopian Airlines has proven that it is possible for an airline to grow their business in today’s economy, by expanding into new markets and increasing frequencies. With their fl eet of Bombardier Q400 NextGen aircraft, Ethiopian Airlines has the superior productivity, increased fl exibility and reduced fl ight times they need to increase their capacity and e ciency. The Q400 NextGen aircraft is one of the most technologically advanced regional aircraft in the world. It has an enhanced cabin, low operating costs, low fuel burn and low emissions – providing an ideal balance of passenger comfort and operating economics, with a reduced environmental scorecard. Welcome to the Q economy. www.q400.com Bombardier, NextGen and Q400 are Trademarks of Bombardier Inc. or its subsidiaries. ©2012 Bombardier Inc. All rights reserved. Q400_Get more Ethiopian_A4_Oct26.indd 1 10/26/12 2:36 PM AFRAA Members> AFRAA Partners> RWANDAIR RESULTS EXPANDS ITS CRJ FLEET WITH THE SPEAK CRJ900 NEXTGEN Bombardier congratulates RwandAir on choosing the industry’s best economics and highest commonality. The CRJ900 NextGen will deliver industry-leading results to RwandAir as they expand their network and develop an e cient hub in the heart of Africa. -

Bulletin to TACT Rules Issue 76 & Rates Issue 169 July 1, 2009

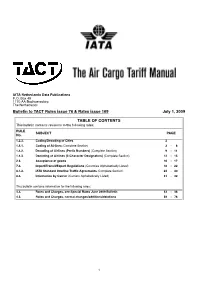

IATA Netherlands Data Publications P.O. Box 49 1170 AA Badhoevedorp The Netherlands Bulletin to TACT Rules issue 76 & Rates issue 169 July 1, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS This bulletin contains revisions to the following rules: RULE SUBJECT PAGE No. 1.2.3. Coding/Decoding of Cities 2 1.4.1. Coding of Airlines (Complete Section) 3- 8 1.4.2. Decoding of Airlines (Prefix Numbers) (Complete Section) 9- 11 1.4.3. Decoding of Airlines (2-Character Designators) (Complete Section) 12 - 15 2.3. Acceptance of goods 16 - 17 7.3. Import/Transit/Export Regulations (Countries Alphabetically Listed) 18 - 22 8.1.2. IATA Standard Interline Traffic Agreements (Complete Section) 23 - 30 8.3. Information by Carrier (Carriers Alphabetically Listed) 31 - 32 This bulletin contains information for the following rates: 4.3. Rates and Charges, see Special Rates June 2009 Bulletin 33 - 38 4.3. Rates and Charges, normal changes/additions/deletions 39 - 76 1 1.2.3. CODING/DECODING OF CITIES A. CODING OF CITIES In addition to the cities in alphabetical order the list below also contains: - Column 1: two-letter codes for states/provinces (See Rule 1.3.2.) - Column 2: two-letter country codes (See Rule 1.3.1.) - Column 3: three-letter city codes Additions: Cities 1 2 3 DEL CARMEN PH IAO NAJAF IQ NJF PSKOV RU PKV TEKIRDAG TR TEQ Changes: Cities 1 2 3 KANDAVU FJ KDV SANLIURFA TR SFQ B. DECODING OF CITIES In addition to the three-letter city codes (Column 1) in alphabetical order the list below also contains: - Column Cities: full name - Column 2: two-letter codes for states/provinces (See Rule 1.3.2.) - Column 3: two-letter country codes (See Rule 1.3.1.) Additions: 1 Cities 2 3 IAO DEL CARMEN PH NJF NAJAF IQ PKV PSKOV RU TEQ TEKIRDAG TR Changes: 1 Cities 2 3 KDV KANDAVU FJ SFQ SANLIURFA TR Bulletin, TACT Rules & Rates - July 2009 2 1.4.1. -

International Airlines

International Airlines Air Malawi (QM) Tel :255 22 2127746 Holiday Africa Tours and Safaris Fax: 255 22 2112914 Indira Gandhi / Zanaki St, Email: [email protected] P.O. Box 22636 Web: www.airmalawi.com Dar es Salaam Emirates (EK) Tel: +255 22 2116100/ 1/ 2 Ali Hassan Mwinyi Road, Fax: +255 22 2116273 Haidery Plaza, 6th Floor Email: [email protected] PO Box 9594 Web: www.emirates.com Dar es Salaam Air Mozambique™ Tel: +255 (22) 2134600 Harbour View Towers, Ground floor Fax: 255 22 2134601 Samora Avenue Email: [email protected] P.O. Box 38331 Web: www.lam.co.mz/en Dar es Salaam Tel: +255-22 2163917/18/38. Kenya Airways (KQ) Fax: + 255 22 2116 492 Ground Floor Peugeot House Web: www.kenya-airways.com Ali Hassan Mwinyi Road P O Box: 5342 Dar es Salaam South African Airline (SA) Tel: 255 22 2117044-7 Raha Towers Building, Fax: 255 22 2110205 Cnr Bibititi & Maktaba Streets Web: www.flysaa.com Dar es Salaam Tel: +255 (0) 783 111 992 www.air-uganda.com Air Uganda (U7) [email protected] Harbour View Towers J-Mall, Samora Avenue, 1st Floor P.O. Box 22636 Dar es Salaam Swiss International Airline (LX) Tel: +25522211887-0/-1/-2/-3 Swiss City Ticket Office Email: [email protected] Luther House-Sokoine Drive Web:www.swiss.com P.O. Box 2109 Dar Es Salaam Air France - KLM Tel: +255 (0) 22 216391 / 15 Peugeot House, Fax: +255 (0) 22 211 6492 Bibi Titi / Ali Hassan Mwinyi Road Web: www.klm.com Ground Floor Ethiopian Airline (ET) Tel: +255 22 211 7063, T.D.F.L Building Ohio street Fax: +255 22 2116492 P. -

Tourist Attractions in the SADC Countries • 1

The Southern African Development Community What we need to know: According to the CAPS document Item 1 Concepts: Regional Tourism, SADC Item 1 The SADC Member Countries , Capital cities and location on a map Item 1 Gateways: How accessible each country from South Africa (Air, Sea, Road, Rail) Role of RETOSA (Regional Tourism Organisation of South Africa) Item 1 Advantages of regional tourism for South Africa and the Item 1 SADC Member states Item 1 Famous tourist attractions in each SADC country ACRONYMS : • SADC – Southern African Development Community • RTO – Regional Tourism Organisation • RETOSA –Regional Tourism Organisation of Southern Africa • DRC – Democratic Republic of Congo • MSC – Mediterranean Shipping Company WHAT IS REGIONAL TOURISM? • Takes place within a specific geographical area e.g Southern Africa • RTO’s promote the area as a world class destination • They spread the benefits across the region e.g tourists from South Africa can easily visit Zimbabwe and Angola. SADC – Brief Notes • Grew out of anti-apartheid movement • Started in 1994 • SA joined in 1996? WHY • Has 15 Member countries: • Angola, Botswana, Democratic Republic of Congo, Swaziland, Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Madagascar, Mauritius, Mozambique, Malawi, Seychelles, Tanzania, South Africa, Lesotho SADC Countries Southern Africa Trans-Frontier Parks Development Clue • For each SADC country you need to know the following: • Country Int. Major Border Major Airports Harbours Posts roads. Angola Launda Cabinda Nakop From Namibe Lobiti Vioolsdrift Namibia Lubango Luanda Oshikango Haumba Namibe Santa Clara SADC Countries and their Capital Cities: • 1. Angola - Luanda • 2. Botswana - Gabarone • 3. Democratic republic of Congo - Kinshasha • 4. Lesotho - Maseru • 5. Madagascar - Antananarivo • 6.