White Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homeowners Handbook to Prepare for Natural Disasters

HOMEOWNERS HANDBOOK HANDBOOK HOMEOWNERS DELAWARE HOMEOWNERS TO PREPARE FOR FOR TO PREPARE HANDBOOK TO PREPARE FOR NATURAL HAZARDSNATURAL NATURAL HAZARDS TORNADOES COASTAL STORMS SECOND EDITION SECOND Delaware Sea Grant Delaware FLOODS 50% FPO 15-0319-579-5k ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This handbook was developed as a cooperative project among the Delaware Emergency Management Agency (DEMA), the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) and the Delaware Sea Grant College Program (DESG). A key priority of this project partnership is to increase the resiliency of coastal communities to natural hazards. One major component of strong communities is enhancing individual resilience and recognizing that adjustments to day-to- day living are necessary. This book is designed to promote individual resilience, thereby creating a fortified community. The second edition of the handbook would not have been possible without the support of the following individuals who lent their valuable input and review: Mike Powell, Jennifer Pongratz, Ashley Norton, David Warga, Jesse Hayden (DNREC); Damaris Slawik (DEMA); Darrin Gordon, Austin Calaman (Lewes Board of Public Works); John Apple (Town of Bethany Beach Code Enforcement); Henry Baynum, Robin Davis (City of Lewes Building Department); John Callahan, Tina Callahan, Kevin Brinson (University of Delaware); David Christopher (Delaware Sea Grant); Kevin McLaughlin (KMD Design Inc.); Mark Jolly-Van Bodegraven, Pam Donnelly and Tammy Beeson (DESG Environmental Public Education Office). Original content from the first edition of the handbook was drafted with assistance from: Mike Powell, Greg Williams, Kim McKenna, Jennifer Wheatley, Tony Pratt, Jennifer de Mooy and Morgan Ellis (DNREC); Ed Strouse, Dave Carlson, and Don Knox (DEMA); Joe Thomas (Sussex County Emergency Operations Center); Colin Faulkner (Kent County Department of Public Safety); Dave Carpenter, Jr. -

Subtropical Storms in the South Atlantic Basin and Their Correlation with Australian East-Coast Cyclones

2B.5 SUBTROPICAL STORMS IN THE SOUTH ATLANTIC BASIN AND THEIR CORRELATION WITH AUSTRALIAN EAST-COAST CYCLONES Aviva J. Braun* The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania 1. INTRODUCTION With the exception of warmer SST in the Tasman Sea region (0°−60°S, 25°E−170°W), the climate associated with South Atlantic ST In March 2004, a subtropical storm formed off is very similar to that associated with the coast of Brazil leading to the formation of Australian east-coast cyclones (ECC). A Hurricane Catarina. This was the first coastal mountain range lies along the east documented hurricane to ever occur in the coast of each continent: the Great Dividing South Atlantic basin. It is also the storm that Range in Australia (Fig. 1) and the Serra da has made us reconsider why tropical storms Mantiqueira in the Brazilian Highlands (Fig. 2). (TS) have never been observed in this basin The East Australia Current transports warm, although they regularly form in every other tropical water poleward in the Tasman Sea tropical ocean basin. In fact, every other basin predominantly through transient warm eddies in the world regularly sees tropical storms (Holland et al. 1987), providing a zonal except the South Atlantic. So why is the South temperature gradient important to creating a Atlantic so different? The latitudes in which TS baroclinic environment essential for ST would normally form is subject to 850-200 hPa formation. climatological shears that are far too strong for pure tropical storms (Pezza and Simmonds 2. METHODOLOGY 2006). However, subtropical storms (ST), as defined by Guishard (2006), can form in such a. -

Intense Hurricane Activity Over the Past 1500 Years at South Andros

RESEARCH ARTICLE Intense Hurricane Activity Over the Past 1500 Years 10.1029/2019PA003665 at South Andros Island, The Bahamas Key Points: E. J. Wallace1 , J. P. Donnelly2 , P. J. van Hengstum3,4, C. Wiman5, R. M. Sullivan4,2, • Sediment cores from blue holes on 4 2 6 7 Andros Island record intense T. S. Winkler , N. E. d'Entremont , M. Toomey , and N. Albury hurricane activity over the past 1 millennium and a half Massachusetts Institute of Technology/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Joint Program in Oceanography, Woods • Multi‐decadal shifts in Intertropical Hole, Massachusetts, USA, 2Department of Geology and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Convergence Zone position and Hole, Massachusetts, USA, 3Department of Marine Sciences, Texas A&M University at Galveston, Galveston, Texas, USA, volcanic activity modulate the 4Department of Oceanography, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, USA, 5School of Earth and Sustainability, hurricane patterns observed on 6 Andros Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona, USA, U.S. Geological Survey, Florence Bascom Geoscience Center, • Hurricane patterns on Andros Reston, Virginia, USA, 7National Museum of The Bahamas, Nassau, The Bahamas match patterns from the northeastern Gulf of Mexico but are anti‐phased with patterns from New Abstract Hurricanes cause substantial loss of life and resources in coastal areas. Unfortunately, England historical hurricane records are too short and incomplete to capture hurricane‐climate interactions on ‐ ‐ ‐ Supporting Information: multi decadal and longer timescales. Coarse grained, hurricane induced deposits preserved in blue holes • Supporting Information S1 in the Caribbean can provide records of past hurricane activity extending back thousands of years. Here we present a high resolution record of intense hurricane events over the past 1500 years from a blue hole on South Andros Island on the Great Bahama Bank. -

How to End Energy Poverty? Scrutiny of Current EU and Member States Instruments

DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT A: ECONOMIC AND SCIENTIFIC POLICY How to end Energy Poverty? Scrutiny of Current EU and Member States Instruments STUDY Abstract Policymaking to alleviate energy poverty needs to find a balance between short- term remedies and the resolution of long-term drivers of energy poverty. EU policy might need to work towards a) finding a definition of energy poverty; b) supporting national policies financially through EU coordination; and c) setting minimum standards for energy efficiency of buildings and devices. This document was provided by Policy Department A at the request of the Committee on Industry, Research and Energy (ITRE). IP/A/ITRE/2014-06 October 2015 PE 563.472 EN This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Industry, Research and Energy. AUTHORS Katja SCHUMACHER, Öko-Institut e.V. Johanna CLUDIUS, Öko-Institut e.V. Hannah FÖRSTER, Öko-Institut e.V. Benjamin GREINER, Öko-Institut e.V. Katja HÜNECKE, Öko-Institut e.V. Tanja KENKMANN, Öko-Institut e.V. Luc VAN NUFFEL, Trinomics RESPONSIBLE ADMINISTRATOR Frédéric GOUARDÈRES EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Karine GAUFILLET LINGUISTIC VERSIONS Original: EN ABOUT THE EDITOR Policy departments provide in-house and external expertise to support EP committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic scrutiny over EU internal policies. To contact Policy Department A or to subscribe to its newsletter please write to: Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy European Parliament B-1047 Brussels E-mail: [email protected] Manuscript completed in August 2015 © European Union, 2015 This document is available on the Internet at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/studies DISCLAIMER The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament. -

AFTER the STORM: WHY ART STILL MATTERS Amanda Coulson Executive Director, NAGB

Refuge. Contents An open call exhibition of Bahamian art following Hurricane Dorian. Publication Design: Ivanna Gaitor Photography: Jackson Petit Copyright: The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB) 8. Director’s Foreword by Amanda Coulson © 2020 The National Art Gallery of The Bahamas 16. Curator’s Note by Holly Bynoe West and West Hill Streets Nassau, N.P. 23. Writers: Essays/Poems The Bahamas Tel: (242) 328-5800 75. Artists: Works/Plates Email: [email protected] Website: nagb.org.bs 216. Acknowledgements ISBN: 978-976-8221-16-2 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas. Cover: Mystery in da Mangroves, 2019 (New Providence) Lemero Wright Acrylic on canvas 48” x 60” Collection of the artist Pages 6–7: Visitor viewing the artwork “Specimen” by Cydne Coleby. 6 7 AFTER THE STORM: WHY ART STILL MATTERS Amanda Coulson Executive Director, NAGB Like everybody on New Providence and across the other islands of our archipelago, all of the there, who watched and imagined their own future within these new climatic landscapes. team members at the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB) watched and waited with a rock in their bellies and their hearts already broken, as the storm ground slowly past the islands In addition to conceiving this particular show “Refuge,” in order to create space for artists to of Abaco and Grand Bahama. -

Towards a More Realistic Cost–Benefit Analysis—Attempting To

energies Article Towards a More Realistic Cost–Benefit Analysis—Attempting to Integrate Transaction Costs and Energy Efficiency Services Thomas Adisorn 1,* , Lena Tholen 1, Johannes Thema 1 , Hauke Luetkehaus 2, Sibylle Braungardt 3, Katja Huenecke 3 and Katja Schumacher 3 1 Energy, Transport and Climate Policy Division, Wuppertal Institute, Doeppersberg 19, 42103 Wuppertal, Germany; [email protected] (L.T.); [email protected] (J.T.) 2 DLR Institute of Networked Energy Systems, Carl-von-Ossietzky-Str. 15, 26129 Oldenburg, Germany; [email protected] 3 Oeko-Institut e.V., Merzhauser Straße 173, 79100 Freiburg, Germany; [email protected] (S.B.); [email protected] (K.H.); [email protected] (K.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-202-2492-246 Abstract: In order to calculate the financial return of energy efficiency measures, a cost–benefit analy- sis (CBA) is a proven tool for investors. Generally, however, most CBAs for investors have a narrow focus, which is—simply speaking—on investment costs compared with energy cost savings over the life span of the investment. This only provides part of the full picture. Ideally, a comprehensive or extended CBA would take additional benefits as well as additional costs into account. The objective of this paper is to reflect upon integrating into a CBA two important cost components: transaction costs and energy efficiency services—and how they interact. Even though this concept has not been carried out to the knowledge of the authors, we even go a step further to try to apply this idea. In so doing, we carried out a meta-analysis on relevant literature and existing data and interviewed a limited number of energy experts with comprehensive experience in carrying out energy services. -

Climate Change Adaptation for Seaports and Airports

Climate change adaptation for seaports and airports Mark Ching-Pong Poo A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Liverpool John Moores University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2020 Contents Chapter 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 20 1.1. Summary ...................................................................................................................... 20 1.2. Research Background ................................................................................................. 20 1.3. Primary Research Questions and Objectives ........................................................... 24 1.4. Scope of Research ....................................................................................................... 24 1.5. Structure of the thesis ................................................................................................. 26 Chapter 2 Literature review ............................................................................................. 29 2.1. Summary ...................................................................................................................... 29 2.2. Systematic review of climate change research on seaports and airports ............... 29 2.2.1. Methodology of literature review .............................................................................. 29 2.2.2. Analysis of studies ...................................................................................................... -

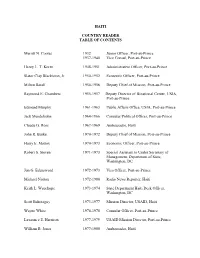

HAITI COUNTRY READER TABLE of CONTENTS Merritt N. Cootes 1932

HAITI COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Merritt N. Cootes 1932 Junior Officer, Port-au-Prince 1937-1940 Vice Consul, Port-au-Prince Henry L. T. Koren 1948-1951 Administrative Officer, Port-au-Prince Slator Clay Blackiston, Jr. 1950-1952 Economic Officer, Port-au-Prince Milton Barall 1954-1956 Deputy Chief of Mission, Port-au-Prince Raymond E. Chambers 1955-1957 Deputy Director of Binational Center, USIA, Port-au-Prince Edmund Murphy 1961-1963 Public Affairs Office, USIA, Port-au-Prince Jack Mendelsohn 1964-1966 Consular/Political Officer, Port-au-Prince Claude G. Ross 1967-1969 Ambassador, Haiti John R. Burke 1970-1972 Deputy Chief of Mission, Port-au-Prince Harry E. Mattox 1970-1973 Economic Officer, Port-au-Prince Robert S. Steven 1971-1973 Special Assistant to Under Secretary of Management, Department of State, Washington, DC Jon G. Edensword 1972-1973 Visa Officer, Port-au-Prince Michael Norton 1972-1980 Radio News Reporter, Haiti Keith L. Wauchope 1973-1974 State Department Haiti Desk Officer, Washington, DC Scott Behoteguy 1973-1977 Mission Director, USAID, Haiti Wayne White 1976-1978 Consular Officer, Port-au-Prince Lawrence E. Harrison 1977-1979 USAID Mission Director, Port-au-Prince William B. Jones 1977-1980 Ambassador, Haiti Anne O. Cary 1978-1980 Economic/Commercial Officer, Port-au- Prince Ints M. Silins 1978-1980 Political Officer, Port-au-Prince Scott E. Smith 1979-1981 Head of Project Development Office, USAID, Port-au-Prince Henry L. Kimelman 1980-1981 Ambassador, Haiti David R. Adams 1981-1984 Mission Director, USAID, Haiti Clayton E. McManaway, Jr. 1983-1986 Ambassador, Haiti Jon G. -

Ambient Outdoor Heat and Heat-Related Illness in Florida

AMBIENT OUTDOOR HEAT AND HEAT-RELATED ILLNESS IN FLORIDA Laurel Harduar Morano A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Epidemiology in the Gillings School of Global Public Health. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Steve Wing David Richardson Eric Whitsel Charles Konrad Sharon Watkins © 2016 Laurel Harduar Morano ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Laurel Harduar Morano: Ambient Outdoor Heat and Heat-related Illness in Florida (Under the direction of Steve Wing) Environmental heat stress results in adverse health outcomes and lasting physiological damage. These outcomes are highly preventable via behavioral modification and community-level adaption. For prevention, a full understanding of the relationship between heat and heat-related outcomes is necessary. The study goals were to highlight the burden of heat-related illness (HRI) within Florida, model the relationship between outdoor heat and HRI morbidity/mortality, and to identify community-level factors which may increase a population’s vulnerability to increasing heat. The heat-HRI relationship was examined from three perspectives: daily outdoor heat, heat waves, and assessment of the additional impact of heat waves after accounting for daily outdoor heat. The study was conducted among all Florida residents for May-October, 2005–2012. The exposures of interest were maximum daily heat index and temperature from Florida weather stations. The outcome was work-related and non-work-related HRI emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths. A generalized linear model (GLM) with an overdispersed Poisson distribution was used. -

Hurricane Andrew in Florida: Dynamics of a Disaster ^

Hurricane Andrew in Florida: Dynamics of a Disaster ^ H. E. Willoughby and P. G. Black Hurricane Research Division, AOML/NOAA, Miami, Florida ABSTRACT Four meteorological factors aggravated the devastation when Hurricane Andrew struck South Florida: completed replacement of the original eyewall by an outer, concentric eyewall while Andrew was still at sea; storm translation so fast that the eye crossed the populated coastline before the influence of land could weaken it appreciably; extreme wind speed, 82 m s_1 winds measured by aircraft flying at 2.5 km; and formation of an intense, but nontornadic, convective vortex in the eyewall at the time of landfall. Although Andrew weakened for 12 h during the eyewall replacement, it contained vigorous convection and was reintensifying rapidly as it passed onshore. The Gulf Stream just offshore was warm enough to support a sea level pressure 20-30 hPa lower than the 922 hPa attained, but Andrew hit land before it could reach this potential. The difficult-to-predict mesoscale and vortex-scale phenomena determined the course of events on that windy morning, not a long-term trend toward worse hurricanes. 1. Introduction might have been a harbinger of more devastating hur- ricanes on a warmer globe (e.g., Fisher 1994). Here When Hurricane Andrew smashed into South we interpret Andrew's progress to show that the ori- Florida on 24 August 1992, it was the third most in- gins of the disaster were too complicated to be ex- tense hurricane to cross the United States coastline in plained by thermodynamics alone. the 125-year quantitative climatology. -

Chlorophyll Variations Over Coastal Area of China Due to Typhoon Rananim

Indian Journal of Geo Marine Sciences Vol. 47 (04), April, 2018, pp. 804-811 Chlorophyll variations over coastal area of China due to typhoon Rananim Gui Feng & M. V. Subrahmanyam* Department of Marine Science and Technology, Zhejiang Ocean University, Zhoushan, Zhejiang, China 316022 *[E.Mail [email protected]] Received 12 August 2016; revised 12 September 2016 Typhoon winds cause a disturbance over sea surface water in the right side of typhoon where divergence occurred, which leads to upwelling and chlorophyll maximum found after typhoon landfall. Ekman transport at the surface was computed during the typhoon period. Upwelling can be observed through lower SST and Ekman transport at the surface over the coast, and chlorophyll maximum found after typhoon landfall. This study also compared MODIS and SeaWiFS satellite data and also the chlorophyll maximum area. The chlorophyll area decreased 3% and 5.9% while typhoon passing and after landfall area increased 13% and 76% in SeaWiFS and MODIS data respectively. [Key words: chlorophyll, SST, upwelling, Ekman transport, MODIS, SeaWiFS] Introduction runoff, entrainment of riverine-mixing, Integrated Due to its unique and complex geographical Primary Production are also affected by typhoons environment, China becomes a country which has a when passing and landfall25,26,27,28&29. It is well known high frequency of natural disasters and severe that, ocean phytoplankton production (primate influence over coastal area. Since typhoon causes production) plays a considerable role in the severe damage, meteorologists and oceanographers ecosystem. Primary production can be indexed by have studied on the cause and influence of typhoon chlorophyll concentration. The spatial and temporal for a long time. -

Extremeearth Preparatory Project

ExtremeEarth Preparatory Project ExtremeEarth-PP No.* Participant organisation name Short Country 1 EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR MEDIUM-RANGE WEATHER FORECASTS ECMWF INT/ UK (Co) 2 UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD UOXF UK 3 MAX-PLANCK-GESELLSCHAFT MPG DE 4 FORSCHUNGSZENTRUM JUELICH GMBH FZJ DE 5 ETH ZUERICH ETHZ CH 6 CENTRE NATIONAL DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE CNRS CNRS FR 7 FONDAZIONE CENTRO EURO-MEDITERRANEOSUI CAMBIAMENTI CMCC IT CLIMATICI 8 STICHTING NETHERLANDS ESCIENCE CENTER NLeSC NL 9 STICHTING DELTARES Deltares NL 10 DANMARKS TEKNISKE UNIVERSITET DTU DK 11 JRC -JOINT RESEARCH CENTRE- EUROPEAN COMMISSION JRC INT/ BE 12 BARCELONA SUPERCOMPUTING CENTER - CENTRO NACIONAL DE BSC ES SUPERCOMPUTACION 13 STICHTING INTERNATIONAL RED CROSS RED CRESCENT CENTRE RedC NL ON CLIMATE CHANGE AND DISASTER PREPAREDNESS 14 UNITED KINGDOM RESEARCH AND INNOVATION UKRI UK 15 UNIVERSITEIT UTRECHT UUT NL 16 METEO-FRANCE MF FR 17 ISTITUTO NAZIONALE DI GEOFISICA E VULCANOLOGIA INGV IT 18 HELSINGIN YLIOPISTO UHELS FI ExtremeEarth-PP 1 Contents 1 Excellence ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.1 Vision and unifying goal .............................................................................................................................. 3 1.1.1 The need for ExtremeEarth ................................................................................................................... 3 1.1.2 The science case ..................................................................................................................................