South Tunisian Gas Pipeline (STGP) Project COUNTRY: Tunisia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2020 Contract Pipeline

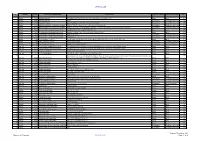

OFFICIAL USE No Country DTM Project title and Portfolio Contract title Type of contract Procurement method Year Number 1 2021 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways SupervisionRehabilitation Contract of Tirana-Durres for Rehabilitation line and ofconstruction the Durres of- Tirana a new Railwaylink to TIA Line and construction of a New Railway Line to Tirana International Works Open 2 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Airport Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 3 Albania 48466 Albanian Railways Asset Management Plan and Track Access Charges Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 4 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Albania: Tourism-led Model For Local Economic Development Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 5 Albania 49351 Albania Infrastructure and tourism enabling Infrastructure and Tourism Enabling Programme: Gender and Economic Inclusion Programme Manager Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 6 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Rehabilitation of Vlore - Orikum Road (10.6 km) Works Open 2022 7 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Upgrade of Zgosth - Ura e Cerenecit road Section (47.1km) Works Open 2022 8 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity Works supervision Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 9 Albania 50123 Regional and Local Roads Connectivity PIU support Consultancy Competitive Selection 2021 10 Albania 51908 Kesh Floating PV Project Design, build and operation of the floating photovoltaic plant located on Vau i Dejës HPP Lake Works Open 2021 11 Albania 51908 -

S.No Governorate Cities 1 L'ariana Ariana 2 L'ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 L'ariana Kalâat El-Andalous 4 L'ariana Raoued 5 L'aria

S.No Governorate Cities 1 l'Ariana Ariana 2 l'Ariana Ettadhamen-Mnihla 3 l'Ariana Kalâat el-Andalous 4 l'Ariana Raoued 5 l'Ariana Sidi Thabet 6 l'Ariana La Soukra 7 Béja Béja 8 Béja El Maâgoula 9 Béja Goubellat 10 Béja Medjez el-Bab 11 Béja Nefza 12 Béja Téboursouk 13 Béja Testour 14 Béja Zahret Mediou 15 Ben Arous Ben Arous 16 Ben Arous Bou Mhel el-Bassatine 17 Ben Arous El Mourouj 18 Ben Arous Ezzahra 19 Ben Arous Hammam Chott 20 Ben Arous Hammam Lif 21 Ben Arous Khalidia 22 Ben Arous Mégrine 23 Ben Arous Mohamedia-Fouchana 24 Ben Arous Mornag 25 Ben Arous Radès 26 Bizerte Aousja 27 Bizerte Bizerte 28 Bizerte El Alia 29 Bizerte Ghar El Melh 30 Bizerte Mateur 31 Bizerte Menzel Bourguiba 32 Bizerte Menzel Jemil 33 Bizerte Menzel Abderrahmane 34 Bizerte Metline 35 Bizerte Raf Raf 36 Bizerte Ras Jebel 37 Bizerte Sejenane 38 Bizerte Tinja 39 Bizerte Saounin 40 Bizerte Cap Zebib 41 Bizerte Beni Ata 42 Gabès Chenini Nahal 43 Gabès El Hamma 44 Gabès Gabès 45 Gabès Ghannouch 46 Gabès Mareth www.downloadexcelfiles.com 47 Gabès Matmata 48 Gabès Métouia 49 Gabès Nouvelle Matmata 50 Gabès Oudhref 51 Gabès Zarat 52 Gafsa El Guettar 53 Gafsa El Ksar 54 Gafsa Gafsa 55 Gafsa Mdhila 56 Gafsa Métlaoui 57 Gafsa Moularès 58 Gafsa Redeyef 59 Gafsa Sened 60 Jendouba Aïn Draham 61 Jendouba Beni M'Tir 62 Jendouba Bou Salem 63 Jendouba Fernana 64 Jendouba Ghardimaou 65 Jendouba Jendouba 66 Jendouba Oued Melliz 67 Jendouba Tabarka 68 Kairouan Aïn Djeloula 69 Kairouan Alaâ 70 Kairouan Bou Hajla 71 Kairouan Chebika 72 Kairouan Echrarda 73 Kairouan Oueslatia 74 Kairouan -

La Liste De La Codification Normalisée Des Agences Bancaires En 2018

APTBEF/SLF 26/07/2019 La liste de la codification Normalisée des succursales de la BCT, des agences Bancaires et des centres d'exploitation régionaux des C.C.P EN 2018 1 Succursales de la Banque Centrale de Tunisie Date Code Succursales Gouvernorat ADRESSE Tél Fax Mail Responsable d'ouverture BCT Tunis Tunis 03/11/1958 25, Rue Hédi Nouira 024 71 122 708 71 254 675 [email protected] Malek DISS Bizerte Bizerte 03/11/1958 Rue Mongi Slim 025 72 431 056 72 431 366 [email protected] Nawel BEN JABALLAH Gabès Gabès 15/09/1980 1, Avenue Mohamed Ali 026 75 271 477 75 274 541 [email protected] Najla Missaoui Nabeul Nabeul 19/01/1979 Rue Taïeb M'Hiri 027 72 286 823 72 287 049 [email protected] Lotfi Dougaz Mohamed Habib Sfax Sfax 03/11/1958 Avenue de la Liberté 14 Janvier 2011 028 74 400 500 74 401 900 [email protected] MASMOUDI Sousse Sousse 03/11/1958 Place Farhat Hached 029 73 225 144 73 225 031 [email protected] Ali Kitar Gafsa Gafsa 11/03/1985 4, Avenue de l'Environnement 030 76 224 500 76 224 900 [email protected] Ali Ben Salem Kasserine Kasserine 07/04/1986 1, Avenue de la Révolution 14 Janvier 2011 031 77 474 352 77 473 811 [email protected] Cherif Amayra Kairouan Kairouan 22/02/1988 1, Rue Beit Al Hikma 032 77 233 777 77 235 844 [email protected] Ali Riahi Médenine Médenine 05/09/1988 8, Avenue Habib Bourguiba 033 75 642 244 75 642 245 [email protected] Ajmi Bellil Jendouba Jendouba 21/08/1989 Rue Abou El Kacem Chebbi 034 78 603 058 78 603 435 [email protected] Brahim Kouki Monastir Monastir 21/05/1990 Rue des Martyrs 035 73 464 200 73 464 203 [email protected] Mohamed Selmi 2 ARAB TUNISIAN BANK Code BIC: ATBKTNTT Date Code Agences GOUVERNORAT ADRESSE Tél. -

Caractérisation De La Dynamique Des Oasis De Djérid Cherine Ben Khalfallah

Caractérisation de la dynamique des oasis de Djérid Cherine Ben Khalfallah To cite this version: Cherine Ben Khalfallah. Caractérisation de la dynamique des oasis de Djérid. Autre. Université Montpellier; Université de Tunis El Manar, 2019. Français. NNT : 2019MONTG010. tel-02166271 HAL Id: tel-02166271 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02166271 Submitted on 26 Jun 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. THÈSE POUR OBTENIR LE GRADE DE DOCTEUR DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DE MONTPELLIER En Géosciences École doctorale GAIA Unité de recherche UMR ESPACE-DEV En partenariat international avec l’Université de TUNIS EL MANAR, Tunisie Caractérisation de la dynamique des oasis de Djérid (Tunisie) par télédétection Présentée par Cherine BEN KHALFALLAH Le 12 mars 2019 Sous la codirection de Frédérique SEYLER et de Fadila DARRAGI Devant le jury composé de Vincent CHAPLOT, Directeur de recherche, IRD (France) Président Luc DESCROIX, Directeur de recherche, IRD (France) Rapporteur Mohamed OUESSAR, Maître de Conférences (HDR), IRA (Tunisie) Rapporteur Zohra -

Flore Et Végétation Des Îles Kneiss (Tunisie Sud-Orientale)

NOTE NATURALISTE Juin 2016 Flore et végétation des îles Kneiss (Tunisie sud-orientale) Bilan de la biodiversité végétale terrestre, impacts environnementaux et recommandations de gestion Frédéric MEDAIL (Aix Marseille Université / IMBE, France) Matthieu CHARRIER (Flora Consult, France) Ludovic CHARRIER (MHN Toulon et Var, France) Mohamed CHAIEB (Université de Sfax, Tunisie) En collaboration avec : Avec le soutien de : Note naturaliste PIM 2016 - Flore et végétation des îles Kneiss (Tunisie sud-orientale) 2 Citation du document Pour des fins bibliographiques, citer le présent document comme suit : Médail F., Charrier M., Charrier L. & Chaieb M., 2016 . Flore et végétation des îles Kneiss (Tunisie sud- orientale). Bilan de la biodiversité végétale terrestre, impacts environnementaux et recommandations de gestion. Note naturaliste PIM, Aix-en-Provence : 49 p. Résumé / Abstract RESUME ABSTRACT Ce travail synthétise les résultats de l'étude de la This work summarizes the results of the botanical flore et végétation vasculaires terrestres effectuée and phytoecological study performed on the five sur les cinq îles et îlots de l'archipel des Kneiss islands and islets of the Kneiss archipelago (South- (Tunisie sud-orientale), lors d'une mission de East Tunisia), during a mission of the PIM Initiative in l'Initiative PIM en avril 2015. April 2015. L'histoire de cet environnement micro-insulaire met The history of this micro-insular environment en exergue les profondes modifications dans la highlights the deep physiographical changes induced physiographie de l'archipel du fait de la remontée du by sea level rise since few thousand years. Add to niveau marin depuis quelques milliers d'années. this, the impacts of human and his cattles have À ceci, s'ajoutent les impacts induits par l'homme et caused the local extinction of several shrubs and ses troupeaux qui ont provoqué l'extinction locale de palatable plants formerly censused on the main plusieurs espèces d'arbustes ou de plantes island, El Bessila or Grande Kneiss. -

Tunisia and the Government of People’S Democratic Republic of Algeria Granting a Loan for the Benefit of the Republic of Tunisia

ENGLISH TRANSLATION FOR INFORMATION th Tuesday, 19 Chaâbane 1435 – 17 June 2014 Year 157 N° 48 Contents Laws Organic Law n° 2014-17 dated 12 June 2014, relating to the provisions relating to the transitional justice and affairs related to the period going from 17 December 2010 to 28 February 2011............................................................................................. 481 Law n° 2014-18 dated 12 June 2014, ratifying a financial protocol between the Government of the Republic of Tunisia and the Government of People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria granting a loan for the benefit of the Republic of Tunisia ............... 481 Law n° 2014-19 dated 12 June 2014, ratifying a financial protocol between the Government of the Republic of Tunisia and the Government of the French Republic intended for the realization of an assistance study relating to the renovation project of the railway between Sfax, Gafsa and Gabes................................................................. 481 Law n° 2014-20 dated 12 June 2014, ratifying a financial protocol between the Government of the Republic of Tunisia and the Government of the French Republic granting financial support intended for the renovation project of the railway between Sfax, Gafsa and Gabes................................................................................................. 482 Law n° 2014-21 dated 12 June 2014, ratifying a financial protocol between the Government of the Republic of Tunisia and the Government of the French Republic relating to the granting of financial support intended for the supply project of rolling stock of the rapid rail network of Tunis.......................................................................... 482 Decrees and Ministerial Orders Ministry of Economy and Finance Order of the Minister of Economy and Finance dated 6 June 2014, establishing a permanent advisory commission for the examination of the requests of restitution and lifting of prescription within the Ministry of Economy and Finance................................ -

Views Were Conducted in Four of Them: El Faouar, Essabria Ouest, Essabria Est, and Gidma (Fig

Sobczak-Szelc and Fekih Comparative Migration Studies (2020) 8:8 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-019-0163-1 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Migration as one of several adaptation strategies for environmental limitations in Tunisia: evidence from El Faouar Karolina Sobczak-Szelc1* and Naima Fekih2 * Correspondence: k.sobczak-szelc@ uw.edu.pl Abstract 1Centre of Migration Research, University of Warsaw, Pasteura 7, Water scarcity and management of this problem are increasingly acknowledged in 02-097 Warsaw, Poland development policies as well as in adaptation and migration discourse. In South Full list of author information is Mediterranean countries, insufficient water supplies in oases are the biggest available at the end of the article limitation on yields of sufficient quantity and quality and increase in arable land, in short, the development of agriculture. Insufficient income from agriculture, when it is the main source of revenue, can push people to migrate. However, migration does not have to be the measure of last resort. Proper adaption to this limitation, including proactive migration, can reduce forced movements from this region in the future. The main aim of this paper is to identify and analyse household strategies, including migration, to cope with and adapt to the impact of environmental changes and limitations on agricultural development in the South Mediterranean. This paper is based on field research carried out in the El Faouar oasis area in Tunisia using a mixed-method approach. The results show that the inhabitants of El Faouar must cope with unforeseen crop destruction limiting their daily expenses by selling livestock or, in years of drought, migrating to look for additional sources of income. -

Wordperfect Office Document

Local Adaptations under Tunisian Oasis Climatic Conditions: Characterization of the Best Practices in Water Agricultural Sector 1L. Dhaouadi, 2N. Karbout, 1K. Zammel, 3M.A.S. Wahba and 2S. Abdeyem 1Regional Center for Research in Oasian Agriculture, Km1 Route de Tozeur CP:2260 Deguache, Tunisia 2Arid Regions Institute (IRA), 4119 Medenine, Tunisia 3Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Bejing, China Key words: Oasis, climate change, irrigation water Abstract: For a long time, the governance of water management, date palm, stakeholders, community resources in oases presents great challenges for local and governance national stakeholders with the consideration of economic, social and environmental importance of this complex ecosystem. So, it’s very important to understand its behavior under current and future climate change conditions. This study focuses on diagnosing, identifying, characterizing and capitalizing the most practices of irrigation water management in the Tunisian oasis and selecting the best among them and to disseminate it in the oasis communities through workshops, field days and Corresponding Author: school days. The most capitalized best practices found L. Dhaouadi during this study are: community governance of irrigation Regional Center for Research in Oasian Agriculture, Km1 water distribution in the oases of El Guetar, valorization Route de Tozeur CP:2260 Deguache, Tunisia of the oasis heritage through the labialization SIPAM (case of the historic Oases of Gafsa), Improved gravity Page No.: 57-64 irrigation Basin system under date palm in the Oases, the Volume: 15, Issue 4, 2020 sandy amendment at the level of oasis agricultural parcels, ISSN: 1816-9155 gravity Bubbler irrigation system in date palm groves and Agricultural Journal magnetic treatment of irrigation water and mixing of Copy Right: Medwell Publications irrigation waters to improve their qualities. -

REQUEST for CEO ENDORSEMENT/APPROVAL PROJECT TYPE: FULL-SIZED PROJECT the GEF TRUST FUND S Submission Date: 06/07/2012

REQUEST FOR CEO ENDORSEMENT/APPROVAL PROJECT TYPE: FULL-SIZED PROJECT THE GEF TRUST FUND S Submission Date: 06/07/2012 PART I: PROJECT INFORMATION Expected Calendar (mm/dd/yy) GEFSEC PROJECT ID: 4035 Milestones Dates GEF AGENCY PROJECT ID: P120561 Work Program (for FSPs only) COUNTRY(IES): Tunisia Agency Approval date 11/30/2012 PROJECT TITLE: Ecotourism and Conservation of Desert Implementation Start 01/01/2013 Biodiversity Project Mid-term Evaluation (if planned) 30/06/2016 GEF AGENCY(IES): World Bank Project Closing Date 01/01/2018 OTHER EXECUTING PARTNER(S): DGEQV, DGF, ONTT, CRDAs GEF FOCAL AREA(s): BD and LD GEF-4 STRATEGIC PROGRAM(s): BD1 and BD2; LD-SP1 and LD-SP3 NAME OF PARENT PROGRAM/UMBRELLA PROJECT: MENARID A. PROJECT FRAMEWORK Project Objective: To contribute to the conservation of desert biodiversity in the three targeted National Parks. This will be achieved through the piloting of an improved approach to protected areas management that integrates ecotourism development and community engagement. Indicate Project whether Expected Expected GEF Financing1 Co-Financing1 Total ($) Components Investment, Outcomes Outputs ($) a % ($) b % c=a+ b TA, or STA2 1. Promoting TA 1. Appropriate Draft Decree for 1,552,950 36 1,313,500 27 2,866,450 enabling conditions incentive the revised for PA framework for legislative management, SLM ecotourism framework for scale up and created. PAs is prepared. ecotourism development 2. Policy and Revised Decree regulatory for the frameworks classification of governing the accommodations environment is prepared. and related sectors incorporate 3 additional staff measures to per targeted NP conserve and (1 conservation sustainably use engineer, 1 eco- desert guard/animator biodiversity. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: ICR00004859 IMPLEMENTATION COMPLETION AND RESULTS REPORT TF017362 ON A GRANT Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF US$ 5.76 MILLION TO THE Government of Tunisia FOR THE TN-OASES ECOSYSTEMS AND LIVELIHOODS PROJECT ( P132157 ) Public Disclosure Authorized 18 May 2020 Environment & Natural Resources Global Practice Middle East And North Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Exchange Rate Effective Mrach 19, 20120 Currency Unit = Tunisian Dinar (TND) 2.91 TND = US$1 0.34 US$ = 1 TND FISCAL YEAR July 1 - June 30 Regional Vice President: Ferid Belhaj Country Director: Jesko S. Hentschel Regional Director: Ayat Soliman Practice Manager: Lia Carol Sieghart Task Team Leader(s): Taoufiq Bennouna ICR Main Contributor: Taoufiq Bennouna ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AP Action Plan APIOS Improvement of Irrigation in Southern Oases Program BP Bank Procedure CPF Country Partnership Framework CRRAO Regional Center for Research in Oasis Agriculture CRDA Regional Commission for Agricultural Development CSO Civil Society Organisation DGEQV General Directorate for Environment and Quality of Life ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework ERR Economic Rate of Return GDA Agricultural Development Group GEF Global Environment Facility INRM Integrated Natural Resource Management IRA Institute of Arid Regions ISN Interim Strategic Note LD Land Degradation LDN Land Degradation Neutrality MALE Ministry of Local Affairs and Environment MENA -

Challenging-Agribusiness-And-Building-Alternatives

CHALLENGING AGRIBUSINESS AND BUILDING ALTERNATIVES IN TUNISIA AND MOROCCO Working Group on Food Sovereignty in Tunisia and ATTAC Maroc Written by: Ghassen ben Khelifa Edited by: Hamza Hamouchene and Sam Harris Cover image: Ali Aznague Based on a translation from Arabic by Marwa Ayadi With the support of: War on Want January 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. OVERVIEW ..................................................................................................... 5 2. FOOD SECURITY OR FOOD SOVEREIGNTY? ............................................... 9 A- Food security ................................................................................... 10 B- Food Sovereignty ............................................................................ 11 3. IMPACT OF THE CURRENT AGRICULTURAL MODEL ON EXPORTS IN TUNISIA AND MOROCCO .............................................................................. 13 A- Tunisia : Mass production for export as a priority ....................... 14 B- Morocco : Prioritising exports at the expense of small farme ....... 19 4. THE RIGHT TO LAND ACCESS AND POLICIES OF LAND GRABBING ........ 25 A- Tunisia ............................................................................................... 26 B- Morocco ............................................................................................ 28 5. WATER RESOURCES: SMALL FARMERS FACE WATER SHORTAGES DUE TO EXPORT CAPITALIST AGRICULTURE ............................................................. 31 A- Tunisia ...................................................................................................... -

TUNISIA This Publication Has Been Produced with the Financial Assistance of the European Union Under the ENI CBC

DESTINATION REVIEW FROM A SOCIO-ECONOMIC, POLITICAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL PERSPECTIVE IN ADVENTURE TOURISM TUNISIA This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union under the ENI CBC Mediterranean Sea Basin Programme. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the Official Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Services and Navigation of Barcelona and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union or the Programme management structures. The European Union is made up of 28 Member States who have decided to gradually link together their know-how, resources and destinies. Together, during a period of enlargement of 50 years, they have built a zone of stability, democracy and sustainable development whilst maintaining cultural diversity, tolerance and individual freedoms. The European Union is committed to sharing its achievements and its values with countries and peoples beyond its borders. The 2014-2020 ENI CBC Mediterranean Sea Basin Programme is a multilateral Cross-Border Cooperation (CBC) initiative funded by the European Neighbourhood Instrument (ENI). The Programme objective is to foster fair, equitable and sustainable economic, social and territorial development, which may advance cross-border integration and valorise participating countries’ territories and values. The following 13 countries participate in the Programme: Cyprus, Egypt, France, Greece, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Lebanon, Malta, Palestine, Portugal, Spain, Tunisia. The Managing Authority (JMA) is the Autonomous Region of Sardinia (Italy). Official Programme languages are Arabic, English and French. For more information, please visit: www.enicbcmed.eu MEDUSA project has a budget of 3.3 million euros, being 2.9 million euros the European Union contribution (90%).