Findings of Inquest Into the Death of Sean Sargent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Brisbane Line

1 The Brisbane Line A publication of the Royal United Service Institute Queensland Inc. Promoting Australia’s National Security & Defence A Constituent Body of the Royal United Services Institute of Australia ABN: 91 025 331 202 Tel: (07) 3233 4420 Victoria Barracks, Brisbane QLD 4000 (07) 3233 4616 Correspondence to: Email: [email protected] Victoria Barracks Brisbane Web: www.rusi.org.au ENOGGERA QLD 4051 Patron: Her Excellency, the Governor of Qld, Ms Penelope Wensley, AC Vice Patrons: VOL: 1 ISSUE: 4 MAJGEN S.Smith, DSC , AM AIRCDRE T. Innes CMDR P.Tedman, DSM, ADC, RAN November 2013 Commissioner I. Stewart, APM Management Committee: PRESIDENT’S REPORT President: AIRCDRE Andrew Kilgour, AM Vice Pres (Ops) SQNLDR John Forrest, RFD (Ret’d) Vice Pres (Admin) Mr Peter Mapp Welcome to the November issue of the RUSI Hon. Secretary LTCOL Ian Willoughby, (Ret’d) Hon. Treasurer Mr Barry Dinneen, FCA, FTIA, JP(Qual) Qld newsletter ‘The Brisbane Line’. This will be Hon. Librarian LTCOL Dal Anderson, RFD, ED (Ret’d) the last one for 2013 and a fitting close to a good Asst Sec (Publicity) Mr Duncan McConnell Committee : LTCOL Russell Linwood, ASM year for RUSIQ. Our lectures from August CAPT Neville Jolly (Ret’d) onwards will be reproduced in this issue and the Mr Sean Kenny, ASM Editor Brisbane Line: Mrs Mary Ross February 2014 issue. Inaugural President 1892-94: Our Annual General meeting was held on MAJGEN J F Owen, Commander Qld Defence Force Wednesday, 18 September 2013 following the Past Presidents: monthly lecture. I am pleased to announce that 2009-11 AIRCDRE P W Growder the Committee was elected again for the next 12 2006-09 BRIG W J A Mellor DSC, AM 2003-06 GPCAPT R C Clelland AM months – I look forward to working with the 2001-03 MAJGEN J C Hartley AO team again. -

Local Heritage Register

Explanatory Notes for Development Assessment Local Heritage Register Amendments to the Queensland Heritage Act 1992, Schedule 8 and 8A of the Integrated Planning Act 1997, the Integrated Planning Regulation 1998, and the Queensland Heritage Regulation 2003 became effective on 31 March 2008. All aspects of development on a Local Heritage Place in a Local Heritage Register under the Queensland Heritage Act 1992, are code assessable (unless City Plan 2000 requires impact assessment). Those code assessable applications are assessed against the Code in Schedule 2 of the Queensland Heritage Regulation 2003 and the Heritage Place Code in City Plan 2000. City Plan 2000 makes some aspects of development impact assessable on the site of a Heritage Place and a Heritage Precinct. Heritage Places and Heritage Precincts are identified in the Heritage Register of the Heritage Register Planning Scheme Policy in City Plan 2000. Those impact assessable applications are assessed under the relevant provisions of the City Plan 2000. All aspects of development on land adjoining a Heritage Place or Heritage Precinct are assessable solely under City Plan 2000. ********** For building work on a Local Heritage Place assessable against the Building Act 1975, the Local Government is a concurrence agency. ********** Amendments to the Local Heritage Register are located at the back of the Register. G:\C_P\Heritage\Legal Issues\Amendments to Heritage legislation\20080512 Draft Explanatory Document.doc LOCAL HERITAGE REGISTER (for Section 113 of the Queensland Heritage -

Alternative Media in Brisbane 1965-1985

5535 words Alternative Media in Brisbane: 1965-1985 Stephen Stockwell Brisbane under the Country/National Party governments from 1957 to 1989 is often portrayed as a cultural desert. While there were certainly many ‘Queensland refugees’ who went to the southern states and overseas to realize their creativity, this paper’s review of alternative media in Brisbane between 1965 and 1985 substantiates previous claims that the political repression also encouraged others with radical views to stay to contribute to the extra-parliamentary opposition. The radical movement is revealed as adept at using the products of technological change (including new printing processes, FM radio and light-weight Super 8 and video camera equipment) to create new audiences interested not only in alternative politics but also contemporary creativity. In particular this paper argues that by countering Premier Bjelke-Petersen’s skilful management of the mainstream media, alternative media workers were producing the basis of the thriving creative industry scene that exists in Brisbane today, as well as non-doctrinaire ideas that may have a wider application. Bjelke-Petersen’s Brisbane and the Willis Thesis In his novel Johnno, David Malouf captures the spirit of Brisbane after the Second World War: ‘Our big country town that is still mostly weather-board and one-storey, so little a city… so sleepy, so slatternly so sprawlingly unlovely!’ (Malouf 1975: 51) With little industrial development and mining profits going south or overseas, Brisbane did not have the economic base to sustain the large, lively and well-financed cultural scenes of Sydney and Melbourne. Critics and residents alike accepted Brisbane as provincial, stunted and without a creative spark. -

Defence Housing Australia Annual Report 2013–14: Section 2

02 Portfolio provisioning and management Defence housing requirement > Property provisioning Portfolio management > Major developments 02 Objectives • Housing supplied and managed effectively to meet Defence requirements • Good stakeholder management and public relations Key performance indicator Target Achievement Housing provisioned for Defence against agreed >98.5% 99.4% Portfolio provisioning and management Portfolio provisioning provisioning plan Defence member satisfaction with property 80% 89% Major outcomes 01 02 03 Provided a total Constructed and Achieved overall lease portfolio of 17,590 purchased 662 new additions of 1,537 properties, which met dwellings for Defence against a Corporate the key performance families and a further Plan target of 1,522. measure for housing 120 apartments provisioning. for MCA. 20 Defence Housing Australia 04 05 06 02 Acquired development Continued work on Gained UDIA six leaf sites in Thornton, residential developments EnviroDevelopment Hunter Valley and including 13 sites in certification for Edmondson Park NSW worth $502.9 six residential (NSW), Rockingham million, one site in ACT developments. and Fremantle (WA), worth $46.6 million, Raceview, Ipswich (QLD) 15 sites in QLD worth and the Defence site $433.9 million, six sites in 2CRU, Darwin (NT). NT worth $574.6 million, four sites in WA worth and management Portfolio provisioning $102.4 million, one site in VIC worth $14.0 million and one site in SA worth $30.5 million. 07 08 09 Achieved a net margin Through Defence, Through Defence, for land development received Parliamentary referred the sales of $37.9 million approval for the construction of including sales from construction of 80 houses at RAAF stage three and four 50 houses on RAAF Base Darwin (NT) surplus lots at Breezes Base Tindal (NT). -

Australian Department of Defence Annual Report 2001

DEFENCE ANNUAL REPORT 2001-02 HEADLINE RESULTS FOR 2001-02 Operational S Defence met the Government’s highest priority tasks through: effectively contributing to the international coalition against terrorism playing a major role in assisting East Timor in its transition to independence strengthening Australia’s border security increasing the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) counter-terrorism capability providing substantial assistance to the Bougainville and Solomon Islands’ peace processes supporting civil agencies in curbing illegal fishing in Australian waters. S The ADF was at its highest level of activity since the Vietnam war. Social S 86 per cent of Australians said they were proud of the ADF – the highest figure recorded over the past 20 years. 85 per cent believed the ADF is effective and 87 per cent considered the ADF is well trained. Unacceptable behaviour in the ADF continued to be the community’s largest single concern. (Defence community attitudes tracking, April 2002) S ADF recruiting: Enlistments were up, Separations were down, Army Reserve retention rates were the highest for 40 years. S The new principles-based civilian certified agreement formally recognised a balance between employees’ work and private commitments. S Intake of 199 graduate trainees was highest ever. S Defence was awarded the Australian Public Sector Diversity Award for 2001. HEADLINE RESULTS FOR 2001-02 Financial S Defence recorded a net surplus of $4,410 million (before the Capital Use Charge of $4,634 million), when compared to the revised budget estimate of $4,772 million. S The net asset position is $45,589 million, an increase of $1,319 million or 3% over 2000-01. -

Surveymonkey Analyze

HAVE YOUR SAY SurveyMonkey Q7 Do you have any further comments about a bridge? Answered: 1,094 Skipped: 1,320 # RESPONSES DATE 1 I agree that the potential green space offset would need to be provided and should be a high 5/7/2019 10:31 AM priority. 2 I agree that green spaces needs to be preserved or newly established when the footbridge is 5/6/2019 11:36 AM build. 3 I think the construction of a public discs and bicycle and pedestrian footbridge from Toowong to 5/6/2019 11:11 AM West End would be a welcome public amenity. 4 definitely NOT to be combined with a vehicular bridge, as was suggested a few years ago. NO 5/6/2019 10:08 AM MORE VEHICLES ON OR THROUGH the WEST END PENINSULA 5 I would like to see mopeds too 5/5/2019 7:36 AM 6 Woukd love a bridge but feel it woukd be inappropriate to land the bridge at ferry rd as per your 5/5/2019 1:41 AM map. Surely it woukd start from the new green space being created at the end of Forbes st . 7 This bridge should go across from Forbes Street next to the Boat club as this is the highest and 5/4/2019 8:21 AM shortest part of the river so would limit costs to build. 8 Green space (replacement) a definite. It would be great to see a native garden space, with 5/3/2019 5:39 PM plants indigenous to the area. -

15 February 2012 Senate Additional Estimates

Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade 15 February 2012 Senate Additional Estimates Ql - Detainee Management in Afghanistan Senator Ludlam asked on Wednesday 15 February 2012, Hansard page 32. Can you table as much information as you can on the activities ofthe Inter-agency Detainee Monitoring Team in Afghanistan? Response: As part ofits military operations in Afghanistan, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) conducts detention operations to remove insurgent and criminal elements from the battlefield when required for reasons ofsecurity or where persons are suspected of committing serious crimes. Detention operations contribute to the ongoing security of the local population and Afghanistan and provide the ADF and coalition personnel with a measure offorce protection. ADF personnel are required to treat detainees humanely and with dignity and respect in accordance with Australian values and our domestic and international legal obligations. The proper treatment ofdetainees apprehended by the ADF in Afghanistan fundamentally underpins our legitimacy in the eyes ofthe local population, as well as the international community. After detainees have undergone initial screening and questioning at the ADF screening facility in Uruzgan, they may be transferred to either Afghan custody in Tarin Kot or US custody at the Detention Facility in Parwan (DFiP), or released if there is insufficient evidence to justify their ongoing detention or to support a prosecution through the Afghan judicial system. As part ofAustralia's detainee management framework in Afghanistan, Australian officials monitor detainees transferred to both Afghan and US custody in order to assess their welfare and treatment, including the conditions in which they are detained, in accordance with the detainee transfer arrangements we have with the Afghan and US Governments. -

CONTACT RAR Pages 78-80.Indd

In the early 1980s, the Army began to pay more attention to the northern regions of the nation and THE PILBARA REGIMENT eventually raised Regional Force Surveillance Units, The Pilbara Regiment evolved out of the 5th Independent based on a squadron/troop structure, in the Northern Rifl e Company, which was raised on 26 January 1982. Territory, Western Australia, and north Queensland. RFSUs The fi rst soldiers were enlisted into the unit at Tom Price were created with the aim of fi lling a gap in the ground and Newman in March 1982. At that time, the company surveillance capability of Australia’s northern defence. headquarters comprised fi ve Regular members who It was recognised that a force operating in this austere formed initially at Campbell Barracks, Swanbourne, in environment would require special knowledge and skills Perth, then moved to Port Hedland in December 1982. UNITS that regular forces do not readily possess and so, a key The unit remained an Independent Rifl e Company until A patrolman is feature of the RFSU concept was the valuable contribution 26 January 1985 when it was converted to a Regional self-suffi cient that Indigenous people could make to the Defence of Force Surveillance Unit to provide a reconnaissance and and must be Australia, as they did during WWII. surveillance capability in the Pilbara region of Western capable of Many Indigenous communities are located in remote Australia – and so became The Pilbara Regiment. areas or close to remote vital assets and, as such, can The unit badge depicts an emu over crossed .303 working in provide invaluable local knowledge to RFSU patrols rifl es with the Sturt’s Desert Pea forming the surround, small groups, operating right across the north and west of the continent. -

Pdf, 516.67 KB

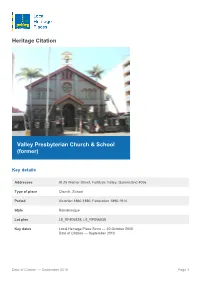

Heritage Citation Valley Presbyterian Church & School (former) Key details Addresses At 25 Warner Street, Fortitude Valley, Queensland 4006 Type of place Church, School Period Victorian 1860-1890, Federation 1890-1914 Style Romanesque Lot plan L8_RP806838; L9_RP806838 Key dates Local Heritage Place Since — 30 October 2000 Date of Citation — September 2010 Date of Citation — September 2010 Page 1 Construction Roof: Corrugated iron; Walls: Masonry - Render People/associations Alexander Brown Wilson and Ronald Martin Wilson - the Sunday School building (Architect); Richard Gailey - Presbyterian Church (Architect) Criterion for listing (A) Historical; (B) Rarity; (D) Representative; (E) Aesthetic; (G) Social; (H) Historical association This Presbyterian Church was constructed in 1885 to a design by influential architect Richard Gailey, while the Sunday School building was designed by honorary Presbyterian architect Alexander Brown Wilson and built in 1906. The church was built at the height of the Valley’s residential boom to accommodate the expanding numbers of Presbyterians in the area. The Sabbath school originally operated from the church building but its popularity encouraged the 1906 construction of the Sabbath school building. The school was extended in 1925 and both the church and school were refurbished in 1935. The church continued to serve the spiritual needs of the local parish through the mid-twentieth century until numbers dwindled. Following the amalgamation of the Methodist, Presbyterian and Congregational churches in 1977, ownership of the building was transferred to the Uniting Church in 1980. In 1989 the building was privately sold and is no longer in use as a church. History The Presbyterian Church had been a force in Brisbane from the early 1850s, and was instrumental in the development of Fortitude Valley. -

Inquiry Into Australia's Involvement in Peacekeeping Operations

Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Inquiry into Australia’s involvement in Peacekeeping Operations; 24 July 2007 Responses to questions taken on notice from the Department of Defence Index of responses to Questions taken on Notice Questions taken on notice during the hearing 1 ADF Peacekeeping Centre 2 ADF language capability 3 ADF language training Written questions received following the hearing W1 Assessing support for peacekeeping operations W2 Additional Army battalions W3 INTERFET leadership W4 Coordination with the UN W5 Coordination with the AFP W6 Division of roles with the AFP W7 Coordination with AusAID W8 Australian Training Support Team East Timor – relationship with other deployed forces W9 Australian Training Support Team East Timor – situational awareness W10 Australian Training Support Team East Timor – chain of command W11 Australian Training Support Team East Timor – legal status W12 Australian Training Support Team East Timor – lessons learnt W13 Medication for ADF personnel W14 Post-deployment medical care W15 Australian Training Support Team East Timor – classification and conditions of service W16 Pre-deployment training W17 Health awareness W18 Post-deployment debriefing W19 UN Senior Mission Leadership courses W20 ADF Peacekeeping Centre W21 ADF Peacekeeping Centre W22 Civil-Military Coordination W23 ADF investigations W24 Lessons learnt W25 Health literacy among peacekeepers W26 Peacekeeping health study W27 Medical records W28 Classification of service W29 Australian Peacekeeping Medal W30 Australian War Memorial Roll of Honour - 1 - Senate Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Inquiry into Australia’s involvement in Peacekeeping Operations; 24 July 2007 Responses to questions taken on notice from the Department of Defence Question 1 ADF Peacekeeping Centre How many people work at the Australian Defence Force Peacekeeping Centre? RESPONSE The authorised establishment of full-time staff at the ADF Peacekeeping Centre is currently two. -

NORFORCE Soldiers Receive Operational Service Medals

NORFORCE soldiers receive Operational Service Medals 1 Fifteen NORFORCE* soldiers have been presented the Operational Service Medal for their service on long-range patrols in northern Australia, as part of Operation RESOLUTE. Operation RESOLUTE is the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) contribution to the whole-of-government effort to protect Australia’s borders and offshore maritime interests Formed in 1981, NORFORCE is one of three Regional Force Surveillance Units (RFSUs) employed in the surveillance and reconnaissance of the remote areas of northern Australia, and its coastline. In the unlikely event of the invasion of northern Australia, NORFORCE and the other RFSUs would operate in a ‘stay behind’ capacity. 2 Receiving their medal at a parade in Darwin on Sunday 7 July 2013, the soldiers are the first of 29 NORFORCE personnel, awarded the medal. The Minister for Defence, Science and Personnel, Warren Snowdon, joined the Unit’s Honorary Colonel and Administrator of the Northern Territory, the Honourable Sally Thomas AM, at the presentation ceremony which marked the 32nd anniversary of the raising of NORFORCE. 3 “Since its formation in 1981, the men and women of the North West Mobile Force have played a crucial role in Australia’s multi-agency border protection activities,” Mr Snowdon said. According to the minister, many of NORFORCE’s soldiers come from remote communities in the region, and Australia relies on their local knowledge and contacts to keep our borders secure. As many soldiers patrol the areas where they are from, a great trust has developed between this regiment and remote Aboriginal communities. ”Today we recognise and thank them for their valuable contribution to Australia’s border security, with this award providing appropriate recognition to all those officers patrolling in often difficult conditions.” he said. -

Former Gona Barracks Kelvin Grove

FORMER GONA BARRACKS KELVIN GROVE FORMER GONA BARRACKS A Conservation Plan for the Queensland University of Technology ■ © COPYRIGHT Allom Lovell Pty Ltd, November 2004 G:\Projects\04015 CreativeInd QUT\Reports\r02.doc FORMER GONA BARRACKS CONTENTS ■ i 1 INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 BACKGROUND 4 1.2 HERITAGE LISTINGS 5 1.3 THIS REPORT 6 THE SITE 6 1.4 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS 7 2 UNDERSTANDING THE PLACE 8 2.1 A MILITARY BARRACKS 8 THE ENDOWMENT 8 FEDERATION AND DEFENCE 9 THE KELVIN GROVE DEFENCE RESERVE 11 THE INTERWAR PERIOD 13 THE SECOND WORLD WAR 16 REGULARS AND RESERVES 19 DISPOSAL OF THE BARRACKS 21 2.2 THE URBAN VILLAGE 22 DEMOLITION 23 CREATIVE INDUSTRIES 23 2.3 THE EARLY BUILDINGS 24 FORMER INFANTRY DRILL HALL (A25) 24 FORMER SERVICES DRILL HALL (A16) 25 THE FRANK MORAN MEMORIAL HALL (A21) 25 FORMER GARAGE AND WORKSHOP BUILDING (A26) 26 FORMER DINING ROOM (A31) 26 FORMER BRIGADE OFFICE (C39) 26 FORMER ARTILLERY DRILL HALL (C39) 27 FORMER GUN PARK (C33) 28 FORMER TOOWONG DRILL HALL (A3) 28 ANCILLARY BUILDINGS 29 THE PARADE GROUND 29 FORMER GONA BARRACKS CONTENTS ■ ii 2.4 VEGETATION 29 3 UNDERSTANDING CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE 31 3.1 CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE 31 3.2 ANALYSIS 31 MILITARY BARRACKS 31 DRILL HALLS 33 3.3 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 38 EXTENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 39 3.4 PREVIOUS ASSESSMENTS 40 4 CONSERVATION POLICY 44 4.1 GENERAL PRINCIPLES 44 THE BURRA CHARTER 44 ENDORSEMENT AND REVIEW 45 STATUTORY REQUIREMENTS 45 SCOPE OF POLICIES 46 4.2 APPROACH 46 4.3 CONSERVATION OF BUILDING FABRIC 48 4.4 ADAPTATION OF BUILDING FABRIC 48 CREATIVE INDUSTRIES PRECINCT 49 4.5 REMOVAL OF BUILDINGS 49 4.6 NEW USES 50 4.7 NEW CONSTRUCTION 50 FORMER GONA BARRACKS CONTENTS ■ iii THE PARADE GROUND 50 4.8 INTERPRETATION 51 5 APPENDIX 52 5.1 NOTES 52 FORMER GONA BARRACKS 1 INTRODUCTION ■ 4 1 INTRODUCTION he former Gona Barracks is currently being redeveloped as part of T the Kelvin Grove Urban Village, a mixed use development containing residential, commercial and educational facilities and associated infrastructure.