BLACKFORD RESERVE KIN S 06 Place Name and Address

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GENERAL MEETING AGENDA Friday 8Th February 2019 10.00Am – 1.00Pm Host – Kingston District Council 29 Holland Street, Kingston SE SA 5275

GENERAL MEETING AGENDA Friday 8th February 2019 10.00am – 1.00pm Host – Kingston District Council 29 Holland Street, Kingston SE SA 5275 Program 9.30am Registration and Morning Tea 10.00am Opening and President’s Welcome 10.05am LCLGA Annual General Meeting 10.25am Close of the LC LGA Annual General Meeting 10.30am Guest Speakers Frank Brennan Chairman SANFL Regional Football Council – South East 10.50am Pippa Pech, Zone Emergency Management Program Officer, SES 11.10am John Chapman Small Business Commissioner, South Australia 11.30am Open of the LC LGA General Meeting 1.00pm Close of the LC LGA General Meeting 1.10pm Lunch 1 AGENDA FOR THE ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF THE LIMESTONE COAST LOCAL GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION TO BE HELD KINGSTON DISTRICT COUNCIL ON FRIDAY 8TH FEBRUARY 2019, STARTING AT 10AM 1.0 MEMBERS/DEPUTY MEMBERS 1.1 Present Naracoorte Lucindale Council Mayor Erika Vickery (LC LGA Interim President) City of Mount Gambier Mayor Lynnette Martin Mayor Des Noll Wattle Range Council Cr Glenn Brown District Council of Grant Mayor Richard Sage (Interim LCLGA Vice President) Mayor Kay Rasheed Kingston District Council Cr Jodie Gluyas District Council of Robe Mayor Alison Nunan Mayor Graham Excell Tatiara District Council Cr Robert Mock 1.2 In Attendance LC LGA Mrs Biddie Shearing (Interim EO) City of Mount Gambier Mr Mark McShane (CEO) District Council of Grant Mr David Singe (CEO) Wattle Range Council Mr Ben Gower (CEO) Naracoorte Lucindale Council Mr Trevor Smart (CEO) District Council of Robe Mr Roger Sweetman (CEO) Kingston District -

Registered Starclubs

STARCLUB Registered Organisations Level 1 - REGISTERED in STARCLUB – basic information supplied Level 2 - SUBMITTED responses to all questions/drop downs Level 3 - PROVISIONAL ONLINE STATUS - unverified Level 4 - Full STARCLUB RECOGNITION Organisation Sports Council SC Level 1st Hillcrest Scout Group Scout Group Port Adelaide Enfield 3 (City of) 1st Nuriootpsa Scout Group Youth development Barossa Council 3 1st Strathalbyn Scouts Scouts Alexandrina Council 1 1st Wallaroo Scout Group Outdoor recreation and Yorke Peninsula 3 camping Council 3ballsa Basketball Charles Sturt (City of) 1 Acacia Calisthenics Club Calisthenics Mount Barker (District 2 Council of) Acacia Gold Vaulting Club Inc Equestrian Barossa Council 3 Active Fitness & Lifestyle Group Group Fitness Adelaide Hills Council 1 Adelaide Adrenaline Ice Hockey Ice Hockey West Torrens (City of) 1 Adelaide and Suburban Cricket Association Cricket Marion (City of) 2 Adelaide Archery Club Inc Archery Adelaide City Council 2 Adelaide Bangladesh Tigers Sporting & Cricket Port Adelaide Enfield 3 Recreati (City of) Adelaide Baseball Club Inc. Baseball West Torrens (City of) 2 Adelaide Boomers Korfball Club Korfball Onkaparinga (City of) 2 Adelaide Bowling Club Bowls Adelaide City Council 2 Adelaide Bushwalkers Inc Bushwalker Activities Adelaide City Council 1 Adelaide Canoe Club Canoeing Charles Sturt (City of) 2 Adelaide Cavaliers Cricket Club Cricket Adelaide City Council 1 Adelaide City Council Club development Adelaide City Council 1 Adelaide City Football Club Football (Soccer) Port -

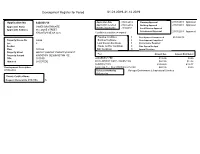

Development Register for Period 01.01.2019-31.12.2019

Development Register for Period 01.01.2019-31.12.2019 Application No 640/001/19 Application Date 07/01/2019 Planning Approval 21/01/2019 Approved Application received 07/01/2019 Building Approval 21/01/2019 Approved Applicants Name JAMES BRAITHWAITE Building Application 7/01/2019 Land Division Approval Applicants Address 66 COOKE STREET Development Approval 21/01/2019 Approved KINGSTON SE SA 5275 Conditions availabe on request Planning Conditions 3 Development Commenced 01/03/2019 Property House No 24ü24 Building Conditions 2 Development Completed Lot 2 Land Division Conditions 0 Concurrence Required Section Private Certifier Conditions 0 Date Appeal Lodged Plan D33844 DAC Conditions 0 Appeal Decision Property Street MARINEüMARINE PARADEüPARADE Fees Amount Due Amount Distributed Property Suburb KINGSTON SEüKINGSTON SE Title 5697/901 LODGEMENT FEE $136.00 $0.00 Hundred LACEPEDE DEVELOPMENT COST - COMPLYING $887.50 $44.38 BUILDING FEES $1,599.20 $101.77 Development Description Septic App. Fee -New CWMS/Onsite/Aerobic $457.00 $0.00 DWELLING Relevant Authority Manager Environment & Inspectorial Services Referred to Private Certifier Name Request Pursuant to R15 (7(b) N Development Register for Period 01.01.2019-31.12.2019 Application No 640/001/20 Application Date 07/01/2020 Planning Approval Application received 07/01/2020 Building Approval Applicants Name DW & SM SIEGERT Building Application 7/01/2020 Land Division Approval Applicants Address PO BOX 613 Development Approval NARACOORTE SA 5271 Conditions availabe on request Planning Conditions -

INVENTORY of ROCK TYPES, HABITATS, and BIODIVERSITY on ROCKY SEASHORES in SOUTH AUSTRALIA's TWO SOUTH-EAST MARINE PARKS: Pilot

INVENTORY OF ROCK TYPES, HABITATS, AND BIODIVERSITY ON ROCKY SEASHORES IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA’S TWO SOUTH-EAST MARINE PARKS: Pilot Study A report to the South Australian Department of Environment, Water, and Natural Resources Nathan Janetzki, Peter G. Fairweather & Kirsten Benkendorff June 2015 1 Table of contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Methods 5 Results 11 Discussion 32 References cited 42 Appendix 1: Photographic plates 45 Appendix 2: Graphical depiction of line-intercept transects 47 Appendix 3: Statistical outputs 53 2 Abstract Geological, habitat, and biodiversity inventories were conducted across six rocky seashores in South Australia’s (SA) two south-east marine parks during August 2014, prior to the final implementation of zoning and establishment of management plans for each marine park. These inventories revealed that the sampled rocky seashores in SA’s South East Region were comprised of several rock types: a soft calcarenite, Mount Gambier limestone, and/or a harder flint. Furthermore, these inventories identified five major types of habitat across the six sampled rocky seashores, which included: emersed substrate; submerged substrate; boulders; rock pools; and sand deposits. Overall, a total of 12 marine plant species and 46 megainvertebrate species were recorded across the six sampled seashores in the Lower South East and Upper South East Marine Parks. These species richness values are considerably lower than those recorded previously for rocky seashores in other parts of SA. Low species richness may result from the type of rock that constitutes south-east rocky seashores, the interaction between rock type and strong wave action and/or large swells, or may reflect the time of year (winter) during which these inventories were conducted. -

The Environmental, Social and Human Health Importance of the Aquifers and Wetlands of the Lower South East of South Australia An

The environmental, social and human health importance of the aquifers and wetlands of the Lower South East of South Australia and SW Victoria and the increasing threats to their existence. My submission to the Senate Select Committee on Unconventional Gas Mining March 2016 I am Marcia Lorenz B.A. Grad. Dip. Ed. Admin., a retired school teacher. I only discovered the attractions of the South East when I came to Beachport 12 years ago. I am a volunteer at the Millicent High School where I support the Aboriginal children in their work with their culture and the environment. I am also a volunteer with other environmental groups in the region. My submission concerns the likely detrimental effect of unconventional gas extraction (“fracking”) on the aquifers and wetlands of the South East of South Australia and therefore on the myriad of species, both flora and fauna that constitute wetland habitats. 1 HISTORY Historically, post white settlement, wetlands were viewed as wastelands with no thought being given to the natural environment and the diversity of species they contained. Economics was the driving force. It would be wonderful if we could say that times have changed and politically there is the realisation that in order for humans to exist, the natural environment must be taken into consideration. After all we now have knowledge that wasn’t available to the ordinary person in the early days of settlement. Post European settlement change in land use has significantly altered the landscape of the South East resulting in the loss of many areas of wetland habitat with <6% of the original wetland extent now remaining.1 An estimated 2,515 km. -

Birds South East

Birds South East Number 84 November 2018 The real highlights for us were seeing Regent Parrots at Lake Hindmarsh, and Malleefowl at three Birdlife Nhill Cross different locations. There was a pair of Malleefowl tending a mound in the reveg patch at the Lodge Border Campout which was a rare opportunity for us to see the birds th working their mound. Unfortunately, it took several September 28 – trips to the mound, just missing the birds each st time, until the last morning of our stay when one of October 1 the birds had just finished opening up the mound and was still present when we arrived. There was a great turn up (over 60) at The Little Desert Nature Lodge for the bi-annual cross border Contents campout. The Nhill Birdlife group did a great job 1. Birdlife Nhill Cross Border Campout organising the weekend for such a large group of people. Stewie and I travelled over on the Thursday 2. Birdata Workshop to give us a bit of time to wander around the Lodge 3. 2018 Twitchathon, Coorong Campout grounds before it got too busy. We managed to find 5. Shorebird Notes the Southern Scrub Robin that we have seen on our 6. Birdlife South East Quiz previous visits, and he was much more co-operative 8. Program, Contacts this time around, allowing us to take a decent photo. We did not have as much luck with the Shy 9. Recent Sightings Of course, we always hope to see a new bird when Heathwren as the bushes that he used to hide in were gone, and we didn’t sight another all weekend. -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

Camping in the District Council of Grant Council Is Working in the Best Interests of Its Community and Visitors to Ensure the Region Is a Great Place to Visit

Camping in the District Council of Grant Council is working in the best interests of its community and visitors to ensure the region is a great place to visit. Approved camping sites located in the District Council of Grant are listed below. Camping in public areas or sleeping in any type of vehicle in any residential or commercial area within the District Council of Grant is not permitted. For a complete list of available accommodation or further information please contact: Phone: 08 8738 3000 Port MacDonnell Community Complex & Visitor Information Outlet Email: [email protected] 5-7 Charles Street Web: portmacdonnell.sa.au OR dcgrant.sa.gov.au Port MacDonnell South Australia 5291 Location Closest Description Facilities Township Port MacDonnell Foreshore Port MacDonnell Powered & unpowered sites, on-site Tourist Park caravans, 20-bed lodge and cabins. Short Ph 08 8738 2095 walk to facilities and centre of town. www.woolwash.com.au 8 Mile Creek Road, Port MacDonnell Pine Country Caravan Park Mount Gambier Powered, unpowered, ensuite, drive thru Ph 8725 1899 sites and cabins. Short walking distance www.pinecountry.com.au from Blue Lake. Cnr Bay & Kilsby Roads, Mount Gambier. Canunda National Park Carpenter Rocks Campsites with varying degrees of access: Number Two Rocks Campground: www.environment.sa.gov.au/parks/Find_a_Park/ 7 unpowered campsites – book online Browse_by_region/Limestone_Coast/canunda- (4 wheel drive access only) national-park Cape Banks Campground: 6 unpowered campsites - book online Designated areas that offer *free camping for **self-contained vehicles only: Tarpeena Sports Ground Tarpeena Donation to Tarpeena Progress Association Edward Street appreciated. -

The Blue Lake - Frequently Asked Questions

The Blue Lake - Frequently Asked Questions FACT SHEET | JULY 2014 FAST FACTS Why does the Lake change Capacity: 30,000 megalitres on current levels. One colour? megalitre is 1000kL, one kilolitre is 1000 litres. The colour change happens over a few days in late November and early December and Depth: Maximum depth of 72m metres continues to deepen during summer. There are many theories about the famous colour Shoreline: Approximately 3.5km kilometres change of the lake, from grey in winter to vivid blue in summer – the following explanation Surface area: Approximately 70ha 59 hectares summarises the general understanding from recent research. Height above sea level: The crater rim is 100m 115 The clear water in the Blue Lake turns vibrant metres above sea level (at its highest point) and the blue in summer for two reasons. First, the Blue Lake water level 11.5m above sea level in 2007. The higher position of the sun in summer means lake level is approximately 28m below Commercial St more light hits the surface of the lake. This level increases the blue light that is scattered back out from the lake by small particles. Pure water Water supply: Currently SA Water pumps an average of tends to scatter light in the blue range, small 3500 megalitres per year particles (such as CaCO3 or calcium carbonate crystals) scatter light in the blue-green range Why is the Lake so blue? and dissolved organic matter (tannins) scatter in the yellow-brown range. The water in the Blue Lake is clear due to During spring the surface of the lake warms, several important natural cleaning processes. -

40 Great Short Walks

SHORT WALKS 40 GREAT Notes SOUTH AUSTRALIAN SHORT WALKS www.southaustraliantrails.com 51 www.southaustraliantrails.com www.southaustraliantrails.com NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Simpson Desert Goyders Lagoon Macumba Strzelecki Desert Creek Sturt River Stony Desert arburton W Tirari Desert Creek Lake Eyre Cooper Strzelecki Desert Lake Blanche WESTERN AUSTRALIA WESTERN Outback Great Victoria Desert Lake Lake Flinders Frome ALES Torrens Ranges Nullarbor Plain NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Simpson Desert Goyders Lagoon Lake Macumba Strzelecki Desert Creek Gairdner Sturt 40 GREAT SOUTH AUSTRALIAN River Stony SHORT WALKS Head Desert NEW SOUTH W arburton of Bight W Trails Diary date completed Trails Diary date completed Tirari Desert Creek Lake Gawler Eyre Cooper Strzelecki ADELAIDE Desert FLINDERS RANGES AND OUTBACK 22 Wirrabara Forest Old Nursery Walk 1 First Falls Valley Walk Ranges QUEENSLAND A 2 First Falls Plateau Hike Lake 23 Alligator Gorge Hike Blanche 3 Botanic Garden Ramble 24 Yuluna Hike Great Victoria Desert 4 Hallett Cove Glacier Hike 25 Mount Ohlssen Bagge Hike Great Eyre Outback 5 Torrens Linear Park Walk 26 Mount Remarkable Hike 27 The Dutchmans Stern Hike WESTERN AUSTRALI WESTERN Australian Peninsula ADELAIDE HILLS 28 Blinman Pools 6 Waterfall Gully to Mt Lofty Hike Lake Bight Lake Frome ALES 7 Waterfall Hike Torrens KANGAROO ISLAND 0 50 100 Nullarbor Plain 29 8 Mount Lofty Botanic Garden 29 Snake Lagoon Hike Lake 25 30 Weirs Cove Gairdner 26 Head km BAROSSA NEW SOUTH W of Bight 9 Devils Nose Hike LIMESTONE COAST 28 Flinders -

Mount Schank Mt Schank

South West Victoria & South East South Australia Craters and Limestone MT GAMBIER Precinct: Mount Schank Mt Schank PORT MacDONNELL How to get there? Mount Schank is 10 minutes south of Mount Gambier along the Riddoch Highway. Things to do: • Two steep walking trails offer a great geological experience. The Mount Schank is a highly prominent volcanic cone Viewing Platform Hike (900m return) begins at the car park located 10 minutes south of Mount Gambier, which and goes to the crater rim. From protrudes above the limestone plain, providing the top, overlooking the nearby panoramic views. quarry, evidence can be seen of the lava flow and changes in the Early explorer Lieutenant James Grant named this fascinating remnant rock formation caused by heat volcano after a friend of his called Captain Schank. and steam. On the southern side The mountain differs from the craters in Mount Gambier in that its of the mountain, a small cone can floor is dry, being approximately at the level of the surrounding plain. be seen which is believed to have been formed by the first of two Evidence suggests two phases of volcanic activity. A small cone on the main stages. southern side of the mount was produced by the early phase, together with a basaltic lava flow to the west (the site of current quarrying • The Crater Floor Walk (1.3km operations). The later phase created the main cone, which now slightly return) also begins in the car park, overlaps the original smaller one and is known as a hybrid maar-cone and winds down to the crater floor structure. -

South Australia

2013 federal election Results Map South Australia N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y Q U E E N S L A N D ! Marla A !Oodnadatta I N Innamincka ! L R A E GREY R T T S ! Coober Pedy S E S O U T H N U W A U S T R A L I A !Marree E A W ! ! ! Leigh Creek ! Cook ! Tarcoola S ! !Glendambo O ! Woomera U Nullarbor ! T H !Hawker Ceduna ! ! W Port Augusta Quorn ! A ! !Orroroo Streaky Bay Whyalla L ! Kimba ! !Peterborough Wudinna ! ! Port Pirie E Great Australian Bight S !Burra Clare ! Spencer ! Kadina Gulf Renmark 100 km ! ! ! Tumby Bay Berri Gawler ! Port Lincoln ADELAIDE Yorketown Gulf St West Point ! Vincent ! Murray Bridge Pinnaroo Cape Spencer ! V Kingscote ! Victor BARKER Harbor I Keith C Cape Gantheaume ! T ! Bordertown O Liberal Cape Jaffa !Kingston SE R Naracoorte! I A Division Boundary Penola ! Millicent ! Division Name Mount Gambier ! Cape Banks The electoral boundaries represented on this map are those in place at the 2013 federal election. 12_0100 Authorised by the Acting Electoral Commissioner, West Block Offices, Queen Victoria Terrace, Parkes, ACT. 2013 federal election Results Map Adelaide area and surrounds M A I N ! Clare N Y O W R H T H 20 km R E I! Saddleworth R R A B ! ! Balaklava Riverton Port Wakefield ! P O R T WAKEFIELD R D Kapunda W ! A r e K iv E R F IE L D D R Y t W Mallala Ligh H ! Freeling ! T R TU H S T R R D O N Gawler ! N I Williamstown A ! M ! Springton ! Elizabeth Birdwood ! ADELAIDE MAYO ! Summertown ! Woodside STH E AS T ERN GULF ST VINCENT Cape ! FW Jervis ! Mount Y Barker ! Callington Kangaroo Island ! Macclesfield Part of 50 km Mclaren MAYO ! Vale ! Strathalbyn ! Willunga ! Australian Labor Party Mount Compass Lake Normanville Alexandrina Liberal ! Division Boundary ! Goolwa ! Division Name Victor Harbor Cape Jervis The electoral boundaries represented on this map are those in place at the 2013 federal election.