The Economic Geography of the Gatwick Diamond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gatwick Diamond Futures Plan

Gatwick Diamond Futures Plan Gatwick Diamond Futures Plan - Report Inspire - Connect – Grow October 2008 1 Gatwick Diamond Futures Plan There is a need to improve the education, learning and skills EXECUTIVE SUMMARY profile of the area to meet future business needs. SMART GROWTH ambitions depend on it; and The Gatwick Diamond Initiative: Vision • The area’s towns do not have the identity and quality of place The Gatwick Diamond Initiative (GDI) is a business led public – that will attract and retain the talented people needed to secure private partnership set up by the Surrey and West Sussex Economic high value added growth. The area needs to improve its Partnerships. The GDI aims to facilitate and co-ordinate the actions infrastructure to grow sustainably and connect the economy to necessary to maintain a vibrant economy. The vision is bold and global value chains. uncompromising: From Good to Remarkable: The Flight Plan “By 2016 the Gatwick Diamond will be a world class, Over the past 18 months since the Gatwick Diamond strategy was internationally recognised business location launched, new working arrangements, plans and investments are achieving sustainable prosperity” being moved forward. We see one of the roles of this plan as Within the GDI steering group local authority partners (Surrey and facilitating the delivery of these. The Futures Plan – “flight plan” - is West Sussex County Councils and the six districts (Crawley, focused on three strategic initiatives. Each initiative has been Horsham, Mid-Sussex, Mole Valley, Reigate and Banstead, developed in consultation with local partners and is based on a Tandridge)) have re-confirmed their commitment to the vision and to commitment to work together to deliver world class assets and working together. -

Crawley Borough Council’S Response to the Commission’S Consultation on a Pattern of Wards for Crawley Was Approved by Full Council at Its Meeting on 4Th April

Cooper, Mark From: Oakley, Andrew Sent: 06 April 2018 17:31 To: Cooper, Mark Subject: Crawley Pattern of wards consultation Hi Mark A document setting out the Crawley Borough Council’s response to the Commission’s consultation on a pattern of wards for Crawley was approved by Full Council at its meeting on 4th April. The resolutions were: RECOMMENDATION 1(a) RESOLVED That Full Council unanimously agreed that the Council’s submission to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England should be for a mixed pattern of Wards (10 Wards served by 3 Councillors and 3 Wards served by 2 Councillors). RECOMMENDATION 1(b) RESOLVED That Full Council approves the mixed pattern of Wards for submission to the Local Government Boundary Commission for England as detailed in the Appendix to the Governance Committee minutes held on 26 March 2018 (i.e. the draft Submission as detailed in Appendix A to report LDS/135, updated to include to the amendments as defined in Appendix C to report LDS/135). The document is quite large due to the number of maps included, so to avoid any problems in sending it by email I have used mailbigfile. You will receive a separate email from mailbigfile with a link to download the document. Many thanks Andrew Oakley Electoral Services Manager Crawley Borough Council 1 Electoral Review of Crawley Borough Council Pattern of Wards April 2018 INTRODUCTION The Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) are conducting a review of the electoral arrangements of Crawley Borough Council during 2018. The Commission monitors levels of electoral equality between wards within each local authority and conducts reviews where changes in population lead to a reduction in the levels of electoral equality. -

The Economic Impact of Gatwick Airport

THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF GATWICK AIRPORT The economic impact of Gatwick Airport TABLE OF CONTENTS Gatwick Airport’s impact on the UK 2 Executive Summary 3 1. Introduction 6 2. Gatwick’s economic impact in 2016 9 2.1 The core impact of Gatwick Airport 9 2.2 The Airport’s catalytic impact 17 2.3 The Airport’s total economic impact 20 3. Gatwick’s future economic impact 22 3.1 Gatwick’s core impact in 2025 22 3.2 Catalytic impact of Gatwick in 2025 24 3.3 What barriers could impede this impact? 25 4. Conclusion 30 5. Appendix 1: Glossary 31 6. Appendix 2: Methodology 32 JANUARY 2017 1 The economic impact of Gatwick Airport GATWICK AIRPORT’S IMPACT ON THE UK Gatwick Airport is a key component of national infrastructure, supporting thousands of jobs and billions in GDP 2016 2025 UNDER A SCENARIO 43 million OF 20% GROWTH IN PASSENGERS PASSENGERS, THE AIRPORT’S FOOTPRINT INCREASES TO £6.5 BILLION 274,000 GDP CONTRIBUTION AIR TRANSPORT MOVEMENTS THE AIRPORT HAS AN ECONOMIC FOOTPRINT OF £5.3 BILLION 85,000 98,000 JOBS GDP CONTRIBUTION JOBS CONNECTIVITY IMPACT MORE THAN TREBLES TO OVER BILLION AROUND 8 MILLION VISITORS £3.8 £1.1 BILLION TO THE UK PASSED THROUGH CONNECTIVITY THE AIRPORT, GENERATING IMPACT FROM BOOST TOURISM SPENDING £6.1 BILLION REACHES GDP CONTRIBUTION £7.5 BILLION AROUND 14% 130,600 JOBS GDP CONTRIBUTION & OF UK TOTAL CONNECTIVITY 154,000 JOBS 2 The economic impact of Gatwick Airport EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ASSESSING GATWICK AIRPORT’S ECONOMIC IMPACT Gatwick Airport’s operations and services deliver very significant economic benefits for the UK as a whole. -

LAST SUITE Remaining 3,897 SQ FT AVAILABLE

LAST SUITE 3,897 SQ FT AVAILABLE GRADE A OFFICE SPACE TO LET REMAI NING MANOR ROYAL CRAWLEY RH10 9AD 20 CAR PARKING SPACES COMTEMPORY EXPOSED SERVICES EPC A RATING themanhattanbuilding.com OVERVIEW The Manhattan Building is fully refurbished with brand new mechanical and electrical services. The offices provide a flexible and efficient working environment, with an outstanding car park ratio. n 3,897 SQ FT Available n Full Category A refurbishment n 20 car parking spaces, a 1:195 ratio n Striking new façade n Contemporary exposed services n Sophisticated reception n 3.3 meter ceiling height n Stylish new toilets and shower facilities n New VRF air conditioning n Cycle Storage n EPC rating of A themanhattanbuilding.com LAYOUT & SPECIFICATION Designed to accommodate the requirements and preferences of a cutting edge occupier, the building offers a high specification office accommodation with contemporary exposed services and a flexible floor plate. This can be fit out as any mix of offices, conference rooms, individual work stations and co-working areas. n Open plan floorplates n Full access raised floors n Brand new individually controlled air conditioning; adjacent units can heat and cool concurrently n LED lighting n Two passenger lifts, each with 10 person capacity n Planned for 1:8 occupational density, comfortably adaptable to 1:6 ratio n EPC rating of A themanhattanbuilding.com LOCATION The Manhattan Building LONDON MANOR ROYAL is situated in a prime HEATHROW BUSINESS location in the south M23/M25 AIRPORT GATWICK EXPRESS DISTRICT Croydon market, next to Gatwick Sutton N Y Airport. The property fronts M3 Manor Royal in Crawley Epsom A2011 Woking M25 Banstead M26 Business Quarter and Catterham A2011 Leatherhead Sevenoaks offers an excellent parking A3 M25 ratio. -

Manor Royal Economic Impact Study Final Report Manor Royal Business District January 2018

Manor Royal Economic Impact Study Final Report Manor Royal Business District January 2018 © 2018 Nathaniel Lichfield & Partners Ltd, trading as Lichfields. All Rights Reserved. Registered in England, no. 2778116. 14 Regent’s Wharf, All Saints Street, London N1 9RL Formatted for double sided printing. Plans based upon Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright reserved. Licence number AL50684A 15885/CGJ/JTi 14791320v3 Manor Royal Economic Impact Study : Final Report Executive Summary This report has been prepared by Lichfields on behalf of the Manor Royal BID Company Limited in partnership with Crawley Borough Council and West Sussex County Council. It presents the results of an Economic Impact Study (EIS) of the Manor Royal Business District in Crawley. The aim of the study is to build on existing evidence to understand the constraints and opportunities that face Manor Royal, consider the different mechanisms that are available to promote economic growth at Manor Royal, and provide recommendations and a way forward that will enable Manor Royal Business District to prosper. The EIS is intended to identify potential actions to allow the Manor Royal Business Improvement District (BID) and its key local authority partners to understand what the future direction of Manor Royal needs to be, practically how this might be delivered and the respective role of each organisation in conjunction with businesses and other stakeholders. The key findings of the study can be summarised as follows: Manor Royal’s Economic Footprint Manor Royal makes a significant contribution to the economy of Crawley and the Gatwick Diamond, employing significant concentrations of people, supporting supply chain jobs and contributing to the public purse. -

Electoral Review of Crawley Borough Council

Electoral Review of Crawley Borough Council Pattern of Wards April 2018 INTRODUCTION The Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) are conducting a review of the electoral arrangements of Crawley Borough Council during 2018. The Commission monitors levels of electoral equality between Wards within each local authority and conducts reviews where changes in population lead to a reduction in the levels of electoral equality. The aim of a review is to establish Ward boundaries that mean each Borough Councillor represents approximately the same number of voters. The electoral arrangements for Crawley were last reviewed in 2002. Development in the Borough since that time, particularly in the Three Bridges Ward has led to electoral inequality between Wards and the review by the LGBCE will address this inequality. The review covers • The number of Councillors to be elected to the Council (Council size) • The number, names and boundaries of Wards • The number of Councillors to be elected for each Ward The Commission has announced that it is minded that Crawley Borough Council should have 36 Borough Councillors and has invited proposals on a pattern of electoral Wards to accommodate those Councillors. This document sets out Crawley Borough Council’s response. The Local Democracy, Economic Development and Construction Act 2009 sets out the criteria that the LGBCE must have regard to in conducting electoral reviews. The Council has developed a proposed pattern of Wards which offer the best balance of these statutory requirements which are: • The need to secure equality of representation • The need to reflect the identities and interests of local communities • The need to secure effective and convenient local government BACKGROUND TO CRAWLEY Crawley is a vibrant town which sits in the heart of the Gatwick Diamond sub region. -

Ifield, Crawley Members Presentation (29Th July 2019) Our Strategic Plan

Making homes happen Land west of Ifield, Crawley Members presentation (29th July 2019) Our strategic plan At Budget 2018, we published our five- year Strategic Plan explaining the steps we’ll take, working collaboratively with the community and in partnership with stakeholders, to do this. Ifield has been identified in the Homes England Strategic Plan as a priority for investment. Within the next few years, we will have invested over £27 billion across our programmes. #MakingHomesHappen Our objectives We’ll unlock public and We’ll ensure a range of investment We’ll improve construction private land where the products are available to support productivity. market will not, to get housebuilding and infrastructure, more homes built where including more affordable housing and they are needed. homes for rent, where the market is not acting. We’ll create a more resilient and We’ll offer expert support for We’ll effectively deliver home competitive market by supporting priority locations, helping to ownership products, providing smaller builders and new entrants, create and deliver more an industry standard service to and promoting better design and ambitious plans to get more consumers. higher quality homes. homes built. #MakingHomesHappen Our track record #MakingHomesHappen Northstowe, Cambridgeshire #MakingHomesHappen Upton, Northamptonshire #MakingHomesHappen Burgess Hill, Mid Sussex #MakingHomesHappen Land west of Ifield #MakingHomesHappen Why here? Regional context • Located at the heart of the Gatwick Diamond economic area • Opportunity -

The Economic Geography of the Gatwick Diamond

The Economic Geography of the Gatwick Diamond Hugo Bessis and Adeline Bailly October, 2017 1 Centre for Cities The economic geography of the Gatwick Diamond • October, 2017 About Centre for Cities Centre for Cities is a research and policy institute, dedicated to improving the economic success of UK cities. We are a charity that works with cities, business and Whitehall to develop and implement policy that supports the performance of urban economies. We do this through impartial research and knowledge exchange. For more information, please visit www.centreforcities.org/about About the authors Hugo Bessis is a Researcher at Centre for Cities [email protected] / 0207 803 4323 Adeline Bailly is a Researcher at Centre for Cities [email protected] / 0207 803 4317 Picture credit “Astral Towers” by Andy Skudder (http://bit.ly/2krxCKQ), licensed under Creative Commons (CC BY-SA 2.0) Supported by 2 Centre for Cities The economic geography of the Gatwick Diamond • October, 2017 Executive Summary The Gatwick Diamond is not only one of the South East’s strongest economies, but also one of the UK’s best performing areas. But growth brings with it a number of pressures too, which need to be managed to maintain the success of the area. This report measures the performance of the Gatwick Diamond relative to four comparator areas in the South East, benchmarking its success and setting out some of the policy challenges for the future. The Gatwick Diamond makes a strong contribution to the UK economy. It performs well above the national average on a range of different economic indicators, such as its levels of productivity, its share of high-skilled jobs, and its track record of attracting foreign investment. -

Local Economy

Crawley Economic Recovery Taskforce (CERT) Group and Town Deal Board Wednesday, 16 September 2020 Meeting Notes ITEM ACTION 1. Welcome Chris Maidment (CM) welcomed everyone to the meeting. Apologies received from: Shelagh Legrave (Chichester College Group) Dave Savage (CCYS) Andrew Clark and Jonathan Rowe (Lloyds Banking Group) Adam Joolia and Ian Ross (Audio Active) Adam Godfrey (SHW) CM extended a special welcome to Jo Ward from Nestle. The minutes of the previous CERT & Town Deal Board (22 July 2020) were accepted. CM thanked everyone for submitting feedback and comments on the draft Town Investment Plan (TIP) and confirmed that the final TIP was submitted to Government on 31 July 2020. CM and PS have considered how best to achieve additional community representation on the Town Deal Board, in the form of specific ‘task and finish’ groups to lead on individual projects. Julie Kapsalis (JK) reported back from the introductory meeting of the Skills sub-group where a key focus was on tangible actions. JK referred to the Government’s recently announced ‘Kickstart Scheme’ on which the Sussex Chamber of Commerce and Chichester College Group are working together to support local businesses to access the scheme. The next meeting of the Skills sub-group will look at how they can further support local people and businesses in this area. The in-meeting chat confirmed a number of partners are also engaged with the Kickstart scheme, including Gatwick Diamond Business, Job Centre Plus and Citizens Advice Bureau. CM reported that Crawley Borough Council is continuing to work with consultants on a draft, revised Economic Growth Assessment in response to the impact of Covid-19 and a draft Economic Development Strategy to support future planning policy. -

The Headquarters Business Location

GDI_6_Data_04.12.13_Layout 1 09/12/2013 12:52 Page 1 Locate in the you will be in good company! The Gatwick Diamond area is located just 30 minutes from central London with Gatwick International Airport at its heart. Global companies and many innovative enterprises have chosen the Gatwick Diamond for their regional headquarters. Dynamic industry clusters include: Life Sciences and Medical Devices; Advanced Manufacturing; Environmental Technologies; Financial and Professional Services; and Food & Beverages. The Headquarters Business Location A selection of some of the business headquarters located in the area. Invest in A Talented & Skilled What Businesses the Gatwick Diamond Workforce are Saying: Multinational companies choose u Here in the Gatwick Diamond, your DMH Stallard helps business es the Gatwick Diamond because of business can bring together a high of all sizes thrive and prosper from its the excellent international calibre and experienced team. The regional centre in Gatwick (Crawley). connectivity, access to talent, and area is home to skilled and well “ With around 200 staff, the firm is quality of life. But don't just take educated employees from senior committed to supporting the region and our word for it... executives and high-achieving works in partnership with some of the graduates to skilled trade largest companies in the South East, professionals. Our move to Crawley represented established SME's and ambitious an exciting new chapter for Nestlé in start-ups. Its regional centre is ideally “ u A well-qualified resident population “the UK. Over the past five years we situated to reach out to businesses with more than a quarter of working have been investing across our across the South and London and is age residents holding a degree or business, transforming our sites and supported by out standing equivalent qualification. -

Jan/Feb 2019 #Gettingbusinessdone Gatwickdiamondbusiness.Com

Jan/Feb 2019 #GettingBusinessDone gatwickdiamondbusiness.com Design By Sponsored By WHAT'S NEW? A message from your Chief Executive International Trade. Please book your place restricts the capacity and reliability of the through our website. Brighton Mainline and so impacts on business in the Gatwick Diamond. On major infrastructure, we have had the publication of the Draft Gatwick Airport On the 17th December, the DfT published Master Plan 2018. Stewart Wingate, the Aviation Strategy Green Paper with Gatwick’s CEO, presented to a strong consultation closing on 11 April 2019. We are gathering of members on 30 November pleased to see that “developing the role of at Hartsfield Manor. We have since airports as catalysts for economic growth” is submitted our response to the consultation one of the policy measures. The consultation emphasising the wider economic importance document is on https://aviationstrategy. of the airport and how this would grow under campaign.gov.uk. We will be responding. the “emergency runway” scenario - without extending the current airport boundaries or All this might look like consultation overload, requiring businesses to relocate. but it is important that the business voice is heard in strategy and investment decisions We also acknowledged that the environmental that impact on the Gatwick Diamond and infrastructure impacts of airport economy. This influencing and lobbying role In the first “the Source” for 2018, we looked expansion need to be carefully managed. is perhaps less obvious than the other ways forward to a year of change with big decisions This will be tested through the planning in which we support our members but, in the on Brexit and key infrastructure investment. -

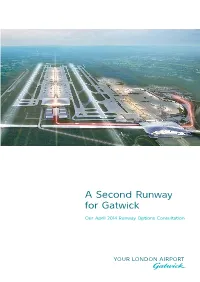

A Second Runway for Gatwick

A Second Runway for Gatwick Our April 2014 Runway Options Consultation 2 Gatwick Runway Options Consultation Contents Foreword 05 Section 1 Our consultation 07 Section 2 Our runway options 11 2.1 Features common to all options 15 2.2 Option descriptions 21 2.3 Airport Surface Access Strategy 29 2.4 Environmental and social effects of the options 43 2.5 Economic effects of a second runway 55 Section 3 Our evaluation of the options 59 Section 4 Community engagement 65 4.1 Working with our communities 66 4.2 Tackling noise 67 4.3 Taking responsibility for our impacts 68 Section 5 Your opportunity to get involved 73 Appendix 1 Policy context 76 Appendix 2 Runway crossings 81 Plan 0A Context plan - Environmental features 93 Plan 1A Option 1 Layout plan 94 Plan 1B Option 1 Boundary plan 95 Plan 1C Option 1 Air Noise Contour plan 96 Plan 2A Option 2 Layout plan 97 Plan 2B Option 2 Boundary plan 98 Plan 2C Option 2 Air Noise Contour plan 99 Plan 3A Option 3 Layout plan 100 Plan 3B Option 3 Boundary plan 101 Plan 3C Option 3 Air Noise Contour plan 102 Gatwick Runway Options Consultation 3 Foreword In its Interim Report published in December 2013, the Airports Commission included Gatwick in its shortlist of potential locations for the next runway in the UK. In 2015, the Airports Commission will recommend to Government where the next runway should be built. We recognise that the local communities around Gatwick will have many questions about what a second runway at Gatwick would mean for them.