Music Services Feasibility Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Activity and Groups Directory

Newport City Council Community Connector Service Directory of Activities Information correct at April 2017 This directory is intended as a local information resource only and Newport City Council neither recommend nor accept any liability for the running of independent support services. You are advised to contact organisations directly as times or locations may change. This directory is available on Newport City Council website: www.newport.gov.uk/communityconnectors 1 Section 1: Community Activities and Groups Page Art, Craft , Sewing and Knitting 3 Writing, Language and Learning 13 BME Groups 18 Card / Board Games and Quiz Nights 19 Computer Classes 21 Library and Reading Groups 22 Volunteering /Job Clubs 24 Special Interest and History 32 Animals and Outdoor 43 Bowls and Football 49 Pilates and Exercise 53 Martial Arts and Gentle Exercise 60 Exercise - Wellbeing 65 Swimming and Dancing 70 Music, Singing and Amateur Dramatics 74 Social Bingo 78 Social Breakfast, Coffee Morning and Lunch Clubs 81 Friendship and Social Clubs 86 Sensory Loss, LGBT and Female Groups 90 Additional Needs / Disability and Faith Groups 92 Sheltered Accommodation 104 Communities First and Transport 110 2 Category Activity Ward/Area Venue & Location Date & Time Brief Outline Contact Details Art Art Class Allt-Yr-Yn Ridgeway & Allt Yr Thursday 10am - Art Class Contact: 01633 774008 Yn Community 12pm Centre Art Art Club Lliswerry Lliswerry Baptist Monday 10am - A club of mixed abilities and open to Contact: Rev Geoff Bland Church, 12pm weekly all. Led by experienced tutors who 01633 661518 or Jenny Camperdown Road, can give you hints and tips to 01633 283123 Lliswerry, NP19 0JF improve your work. -

M06 Ymateb Gan Traddodiadau Cerdd Cymru / Response from Music Traditions Wales

Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru / National Assembly for Wales Pwyllgor Diwylliant, y Gymraeg a Chyfathrebu / Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee Diwydiant Cerddoriaeth yng Nghymru / Music Industry in Wales CWLC M06 Ymateb gan Traddodiadau Cerdd Cymru / Response from Music Traditions Wales How do local authority decisions such as business rates, licensing and planning decisions impact upon live music venues? 1. There is very little that Local authorities can do to promote live music venues unless the council has a live music strategy in place. Without the political directive to recognise and value the local music scene local authorities do not see either their social or economic value and therefore do not take measures to preserve them as part of the Authority’s Plan. 2. It’s possible for a local authority to be imaginative, use Planning Gain to require developers to support live music as a “public art”, make measurable provision of live music a condition of renewing and awarding licences but this needs leadership. 3. In our experience, a local authority’s staff, with one or two exceptions do not know how to recognise the value of a live music venue. The social benefits do not fit into their metrics. Very often a policy that seeks to attract inward investment discounts the value of small businesses. 4. Most live music in Wales does not happen in dedicated venues and theatres. It happens in bars & pubs, social clubs, meantime & pop-up spaces, fields, weddings, festivals. It is frequently a valuable part of a business for the retention of customers etc, but rarely forms the main part of a business’ revenue. -

International Best Practice in Music Performance Education Models and Associated Learning Outcomes for Wales

International Best Practice in Music Performance Education Models and Associated Learning Outcomes for Wales Professor Paul Carr Faculty of Creative Industries The University of South Wales The ATRiuM Cardiff April 2018 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 3 Stakeholder Interviews ......................................................................................................15 Emma Coulthard ..................................................................................................................15 Lucy Green ..........................................................................................................................17 Vanessa Barnes ....................................................................................................................18 Eluned David .......................................................................................................................20 Steve Harker ........................................................................................................................21 Timo Klemettinen ................................................................................................................23 Emma Archer.......................................................................................................................25 David Jackson ......................................................................................................................27 -

Eisteddfod Weekend Flyer

Folk Music Society of New York, Inc. July/August 2009 vol 44, No.7 July 1 Wed Folk Open Sing 7 pm in Brooklyn 10 Fri Beppe Gambetta; 8pm at the West Side Arts Coalition 13 Mon FMSNY Exec. Board Meeting; 7:15pm location tba 18 Sat Chantey Sing at Seamen’s Church Institute, 8pm. August 5 Wed Folk Open Sing 7 pm in Brooklyn 8 Sat Sing and Swim Party, 1 pm at the Cohen’s; Queens 15 Sat Chantey Sing at Seamen’s Church Institute, 8pm. 23 Sun Tom Akstens and Neil Rossi, Free House Concert, 2 pm in Sparrowbush, NY 27 Thur Newsletter Mailing, 7pm in Jackson Heights (Queens) September 2 Wed Folk Open Sing 7 pm in Brooklyn 14 Mon FMSNY Exec. Board Meeting; 7:15pm location tba 17 Thur Gwilym Davies, Carol Davies, and Terry Brenchley house concert, Upper West Side 20 Sun Sacred Harp Singing at St.Bartholomew’s in Manhattan 26 Sat Chantey Sing at Seamen’s Church Institute, 8pm. Table of Contents Society Events Details ...........2-4 Repeating Events ................... 11 Folk Music Society Info ........... 4 Calendar Location Info ...........12 Topical Listing of Society Events 5 Festival Listings ....................14 Help Wanted ......................... 5 Folk Music Week ad ..............20 From The Editor ................... 6 Falcon Ridge Festival Ad .........21 Eisteddfod Weekend flyer .......7-8 30 Years Ago ......................22 Weekend Scholarships ............. 9 Woody Guthrie B’day Bash ad ..22 Calendar Listings .................10 Pinewoods Hot Line ...............23 Details on pages 2-3 Eisteddfod; October 16-18 at Nevele Grande, Ellenville, NY --See pages 7-8 The Society’s web page: www.folkmusicny.org - 1 - Beppe Gambetta, Friday, July 10th, 8 pm Beppe Gambetta is one of the true master innovators of the acoustic guitar. -

Building New Business Strategies for the Music Industry in Wales

Knowledge Exploitation Capacity Development Academic Expertise for Business Building New Business Strategies for the Music Industry in Wales Final report School of Music BANGOR UNIVERSITY This study is funded by an Academia for Business (A4B) grant, which is managed by the Welsh Assembly Government’s Department for Economy and Transport, and is financed by the Welsh Assembly Government and the European Union. 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary.......................................................................................................5 The following conclusions are drawn from this study......................................................5 The following recommendations are made in this study ................................................6 Preface ..............................................................................................................................8 Introduction ....................................................................................................................9 Part 1: Background and Context: The Infrastructure of the WelshLanguage Popular Music Industry from 1965–c.2000......................................................... 12 1.1 Overview...................................................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Record companies and sales .............................................................................................. 13 1.3 TV, radio and Welshlanguage music journalism .................................................... -

Newport and Caerleon

Er mwyn arbed arian Rhesymau da dros deithio o Un o fanteision teithio o gwmpas o dan eich grym eich Rhwydwaith cerdded a beicio gwmpas ar droed, beic, bws hun yw ei fod yn eithriadol o rad. Dim treth car, dim MOT Casnewydd a dim gofidiau petrol. Os byddwch yn cerdded neu’n Datblygwyd y map hwn i’ch cynorthwyo i deithio o neu drên beicio’n rheolaidd fe arbedwch ffortiwn! gwmpas Dinas Casnewydd a’r ardal gyfagos ar droed, Er budd eich iechyd a’ch lles beic a thrafnidiaeth gyhoeddus. Mae pob grid ar y map yn Mae cerdded a beicio i’r gwaith, i’r siopau neu i ymweld Cysylltu eich siwrnai cynrychioli ar gyfartaledd daith 10 munud ar droed neu 4 â ffrindiau a theulu yn ffyrdd ardderchog i gynnwys munud ar feic, gan ddangos pa mor hawdd yw hi i deithio gweithgaredd corfforol rheolaidd yn eich trefn arferol o gwmpas gan ddefnyddio eich nerth eich hun. bob dydd. Gall hyn eich cynorthwyo i losgi calorïau, Cerdded a beicio lleihau colesterol a gostwng pwysedd gwaed. Mae Sustrans. Porwch, lawrlwythwch a chreu mapiau ar-lein Mae’r llwybr astellog gwych ar draws gorlifdir Afon gweithgaredd corfforol rheolaidd hefyd yn gwella eich o lwybrau cerdded a beicio lleol eich hun. Gallwch hefyd Wysg ac adran newydd saith mililitr o hyd yn rhoi llwybr MAP TEITHIO BYW / ACTIVE TRAVEL MAP MAP TEITHIO BYW / ACTIVE TRAVEL hwyliau, eich teimlad o les a gall gynorthwyo i roi hwb blotio eich siwrnai er mwyn ei rhannu gyda ffrindiau a cerdded a beicio uniongyrchol rhwng Casnewydd a i’ch hunan-barch. -

Skull Orchard Revisited Art, Words & Music by Jon Langford with David Langford Photographs by Denis Langford

Skull Orchard Revisited Art, Words & Music by Jon Langford with David Langford Photographs by Denis Langford Verse Chorus Press Portland 7 London 7 Melbourne INTRODUCTION An ugly, lovely town (or so it was and is to me) . This sea town was my world; outside a strange Wales, coal-pitted, mountained, river-run, full, so far as I know, of choirs and football teams and sheep . , moved about its business which was none of mine. – Dylan Thomas, Reminiscences of Childhood I was born on the border, and we talked about ‘the English’ who were not us, and also ‘the Welsh’ who were not us. – Raymond Williams The songs on Skull Orchard are mostly about Newport, the ugly, lovely town I was born in, and the not so strange Wales beyond. My mum was from the valleys and my dad was from the ’Port. Like Raymond Williams, he thought of himself as neither English nor Welsh, but on that point he and my mother would never agree. Her family was full of miners, rugby players, pigeon fanciers – there was even the odd Welsh speaker. I moved up to Leeds in 1976 (the year they closed most of Llanwern steelworks) and then to Chicago in 1992, but the eyes of an exile can’t help looking back, and I can’t help going back there. Newport is full of ghosts for me now, and sometimes when I walk the streets of the town centre I feel like a ghost myself – lost, gone, unrecogniz- able . an invisible man. My dad used to take me and my brother Dave down to the docks on Saturday mornings to see the big Soviet cargo ships and the squat little tugboats. -

Music Industry in Wales Inquiry

June 2019 Music Industry in Wales Culture, Welsh Language and Communications Committee 1. UK Music is the umbrella body representing the collective interests of the UK’s commercial music industry, from songwriters and composers to artists and musicians, studio producers, music managers, music publishers, major and independent record labels, music licensing companies and the live music sector. 2. UK Music exists to represent the UK’s commercial music sector, to drive economic growth and promote the benefits of music to British society. A full list of UK Music members can be found in annex. 3. In the latest edition of our Measuring Music 1 report our research found that the UK Music Industry contributes £4.5 billion GVA to the UK Economy. The music industry also generated £2.6 billion in export revenues. Live music contributes £991m GVA to the economy and generated £80 million in export revenues. The UK Music Industry employs 145,815 people, with 28,659 of these employees being based in the Live sector. Grassroots Music Venues 4. UK Music was supportive of the Save Womanby Street campaign in 2017 working closely with Kevin Brennan MP and Jo Stevens MP on exploring what policy could help save this area of cultural significance due to the number of venues on the street. We have continued our work with Kevin and Jo in advocating for the protection of Welsh grassroots music venues in the Houses of Parliament alongside our partners the Music Venue Trust. 5. Grassroots music venues are often the first step onto the talent pipeline for emerging musicians. -

Petra Kuppers Curriculum Vitae Ypsilanti, Michigan

Petra Kuppers Curriculum Vitae www.olimpias.org Ypsilanti, Michigan EDUCATION Ph.D. 1999 Performance Studies and Feminist Theory, Dissertation Title: 'Between Embodiment and Representation: Performing Bodies, Freaks, Filmdance’, Falmouth College of Arts DiplHSW 1998 Diploma in Health and Social Welfare Studies, Open University, UK M.A. 1993 Film and TV Studies, Dissertation Title: ‘Ethnicity and the Hammer Horror Film’, University of Warwick, UK M.A. 1994 Germanistik, Film, TV and Theatre Studies, Anthropology, Dissertation Title: ‘The Image of the Other in Art Historical and Cultural Historical Perspectives: Native Americans and 19th century German Travel Fiction’, University of Cologne, Germany 2000 Movement Therapy BTEC Award, Dance Voice, Bristol 1998 Two-Year Dance Leaders in the Community Certificate, Laban Guild 1996 Counseling: Further Education Certificate, University of Wales ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE 2012- University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Professor of English and Women’s Studies (Joint Appointment since 2017), courtesy appointments in Art and Design, Theatre and Drama, Faculty Fellow with the Center for World Performance Studies and the Matthaei Botanical Gardens 2006- 2012 University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Associate Professor of English, Art and Design, Theatre and Drama, Women’s Studies (tenured) 2001 -2006 Bryant University, Rhode Island, Assistant and Associate Professor of Performance Studies (promotion to Associate Professor in 2005) 2009- Associate Faculty, Goddard College, Port Townsend, Low-residency MFA in Interdisciplinary -

TIPPS Von 08.05. - 21.05

eit se 785 dreissig 1 GRATIS 1 9 7 9 Q..DEDE Vom Thurgau nach Paraguay oder die wahrscheinlich kleinste Schokofabrik der Welt Radolfzeller Leckerbissen In die Zukunft geschaut -TIPPS von 08.05. - 21.05. Kultur, Szene, Treffpunkt ... QLTIG QLTUR QLTIP CAMPHILL AUSBILDUNGEN Liebe Leser, gGmbH dass man in die Ferne schweifen kann, obwohl das Gute so nah IMPRESSUM ist, zeigen wir im aktuellen QLT einerseits mit Toni Rößlers Ge- schichte über das Entstehen der kleinsten Schoko-Fabrik (S.4/5), CHEFREDAKTION und auch in unserer neuen Serie „Auf ein Wort“ (S. 7) geht es Heilerziehungs- Dani Behnke (daniB) um die Liebe zu einem fernen Land. Aus allen sozialen Berei- AUTOREN & MITARBEITER: chen und allen Altersgruppen stellt QLT bei „Auf ein Wort“ pfleger/-in Carolin Becker Menschen vor, die etwas zu sagen haben. Den Anfang macht Fachschule für Sozialwesen, Harald Borges Rosemarie Müller, die sich seit 20 Jahren ak- Camphill Seminar am Bodensee Krischa Malow tiv für sozialverträglichen Tourismus und di- Beate Nash rekte Entwicklungshilfe in Gambia einsetzt. Altenpfleger/-in Hans-Peter Schulz Und noch eine andere starke Frau aus der Gerhard Zahner QLT-Region stellt uns Beate Nash vor – Berufsfachschule für Altenpflege ANZEIGENDISPOSITION Yvonne Bütehorn von Eschstruth. Die meisten Verkürzte Ausbildung u.a. für Heiler- Birgitt Katterre von uns freuen sich im Frühling über das ziehungs- und Krankenpfleger/-in Peter Wettering fröhliche Vogelgezwitscher, machen sich al- Cornelia Wittwer lerdings kaum Gedanken, welchen Gefahren GESTALTUNG: die Vogelwelt gerade in der Brutzeit ausge- Regina Weißenberger setzt ist. Was tun wenn man einen kleinen DRUCK verletzten Vogel findet? Hier wird Yvonne Druckerei Konstanz GmbH Bütehorn von Eschstruth aktiv (S. -

World Music Festivals in Wales Welshpool

01 02 Llandudno 26 03 28 04 Wrexham 2525 Caernarfon 23 24 05 06 World Music Festivals in Wales Welshpool World Music Festivals in Wales 07 Aberystwyth 27 08 09 Fishguard 22 Carmarthen 21 11 20 12 13 16 19 Abertawe 17 14 15 18 Newport Cardiff 01 06 10 Llandudno Jazz Festival Sesiwn Fawr Dolgellau* Fishguard International When: July When: July Music Festival Where: Llandudno Where: Dolgellau When: July Genre: Jazz Genre: Folk/Celtic Where: Fishguard Three days of the best UK jazz A festival full of the best Welsh Genre: Jazz/Folk/World/Classical alongside a fringe event featuring and Celtic music. Artists are Ten days of world class music set diverse and popular artists and programmed from Wales and against a spectacular backdrop in bands playing jazz, trad jazz with beyond across a weekend. The Pembrokeshire. some Soul, Funk and Blues. whole of Saturday afternoon is www.llandudnojazzfestival.com held on the Sgwâr (town square) www.fishguardmusicfestival.co.uk with a ‘twmpath dawns’ (much 02 like a ceilidh), a procession and 11 March Manouche more. The Laugharne Weekend When: March www.sesiwnfawr.cymru When: April Where: Menai Bridge Where: Laugharne Genre: Gypsy Jazz 07 Genre: All UK Gypsy Jazz Festival which Fire in the Mountain An annual festival which initially focussing on only UK When: May/June concentrates on literature, music acts, the festival is now growing Where: Cwmnewidion Isaf, and comedy, bringing talent from to welcome acts from all over near Aberystwyth all over the world but always the world. Genre: Folk/World maintaining a connection to www.marchmanouche.co.uk A deliberately small and intimate writers and musicians from Wales festival on a farm in the foothills or who have a connection with 03 of the Cambrian mountains. -

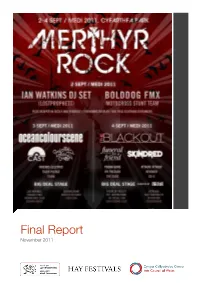

Final Report November 2011 Photos: Madebyfinn.Com

Final Report November 2011 Photos: madebyfinn.com Contents Executive Summary 3 The Future – building a world class 22 experience for Wales The Music – a signature line-up, showcasing the 4 best established and emerging rock Governance & Management 24 Introducing New Voices – a transformational 5 platform for Welsh talent Feedback 25 Supporting Welsh Talent – unprecedented 7 industry opportunities for rising stars Audiences – community engagement without 12 barriers Economic Impact – large scale investment in an 15 under-served area of Wales Environmental Impact – ecologically sound at 17 each stage of development Marketing – putting Wales in the headlines 18 Merthyr Rock Festival, September 2011 3 Executive Summary Merthyr Rock delivered on many levels: exceptional music curation; innovative approaches to education and training; and the transformation of how Merthyr is perceived on a national, and even more crucially, local level. The pilot year has been a wonderful investment in the development of a sustainable music industry celebration. “Proud to say I’m from Merthyr right now.” Alyce Jones, 16 Merthyr Rock Festival, September 2011 4 The Music “This has to happen again... this was the best collection of Welsh acts that has ever been put together.” James McLaren, BBC Wales Music It was the aim of Merthyr Rock to bring an international-standard festival to Merthyr, and to give the Valleys the occasion to match their rich musical heritage. In programming the event it was essential that the festival featured household names that could draw large crowds performing alongside the best of established and emerging Welsh musicians. The headliners in 2011 were Ocean Colour Scene and The Blackout.