Politics & Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Rearticulations of Enmity and Belonging in Postwar Sri Lanka

BUDDHIST NATIONALISM AND CHRISTIAN EVANGELISM: REARTICULATIONS OF ENMITY AND BELONGING IN POSTWAR SRI LANKA by Neena Mahadev A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland October, 2013 © 2013 Neena Mahadev All Rights Reserved Abstract: Based on two years of fieldwork in Sri Lanka, this dissertation systematically examines the mutual skepticism that Buddhist nationalists and Christian evangelists express towards one another in the context of disputes over religious conversion. Focusing on the period from the mid-1990s until present, this ethnography elucidates the shifting politics of nationalist perception in Sri Lanka, and illustrates how Sinhala Buddhist populists have increasingly come to view conversion to Christianity as generating anti-national and anti-Buddhist subjects within the Sri Lankan citizenry. The author shows how the shift in the politics of identitarian perception has been contingent upon several critical events over the last decade: First, the death of a Buddhist monk, which Sinhala Buddhist populists have widely attributed to a broader Christian conspiracy to destroy Buddhism. Second, following the 2004 tsunami, massive influxes of humanitarian aid—most of which was secular, but some of which was connected to opportunistic efforts to evangelize—unsettled the lines between the interested religious charity and the disinterested secular giving. Third, the closure of 25 years of a brutal war between the Sri Lankan government forces and the ethnic minority insurgent group, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), has opened up a slew of humanitarian criticism from the international community, which Sinhala Buddhist populist activists surmise to be a product of Western, Christian, neo-colonial influences. -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10 -

The Sri Lankan Insurgency: a Rebalancing of the Orthodox Position

THE SRI LANKAN INSURGENCY: A REBALANCING OF THE ORTHODOX POSITION A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Peter Stafford Roberts Department of Politics and History, Brunel University April 2016 Abstract The insurgency in Sri Lanka between the early 1980s and 2009 is the topic of this study, one that is of great interest to scholars studying war in the modern era. It is an example of a revolutionary war in which the total defeat of the insurgents was a decisive conclusion, achieved without allowing them any form of political access to governance over the disputed territory after the conflict. Current literature on the conflict examines it from a single (government) viewpoint – deriving false conclusions as a result. This research integrates exciting new evidence from the Tamil (insurgent) side and as such is the first balanced, comprehensive account of the conflict. The resultant history allows readers to re- frame the key variables that determined the outcome, concluding that the leadership and decision-making dynamic within the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) had far greater impact than has previously been allowed for. The new evidence takes the form of interviews with participants from both sides of the conflict, Sri Lankan military documentation, foreign intelligence assessments and diplomatic communiqués between governments, referencing these against the current literature on counter-insurgency, notably the social-institutional study of insurgencies by Paul Staniland. It concludes that orthodox views of the conflict need to be reshaped into a new methodology that focuses on leadership performance and away from a timeline based on periods of major combat. -

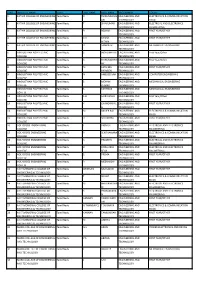

S.No Institute Name State Last Name First Name Programme

S.NO INSTITUTE NAME STATE LAST NAME FIRST NAME PROGRAMME COURSE 1 KATHIR COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING Tamil Nadu R THIRUMURUG ENGINEERING AND ELECTRONICS & COMMUNICATION AN TECHNOLOGY ENGG 2 KATHIR COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING Tamil Nadu T SIVAKUMAR ENGINEERING AND ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICS TECHNOLOGY ENGINEERING 3 KATHIR COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING Tamil Nadu R RESHMI ENGINEERING AND FIRST YEAR/OTHER TECHNOLOGY 4 KATHIR COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING Tamil Nadu K.V KANNA ENGINEERING AND FIRST YEAR/OTHER NITHIN TECHNOLOGY 5 KATHIR COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING Tamil Nadu R SAMPATH ENGINEERING AND MECHANICAL ENGINEERING TECHNOLOGY 6 HINDUSTHAN POLYTECHNIC Tamil Nadu S INDHUMATHI ENGINEERING AND First Year/Other COLLEGE TECHNOLOGY 7 HINDUSTHAN POLYTECHNIC Tamil Nadu K THIRUMOORT ENGINEERING AND First Year/Other COLLEGE HY TECHNOLOGY 8 HINDUSTHAN POLYTECHNIC Tamil Nadu M FATHIMA ENGINEERING AND FIRST YEAR/OTHER COLLEGE PARVEEN TECHNOLOGY 9 HINDUSTHAN POLYTECHNIC Tamil Nadu N ANBUSELVAN ENGINEERING AND COMPUTER ENGINEERING COLLEGE TECHNOLOGY 10 HINDUSTHAN POLYTECHNIC Tamil Nadu S MOHAN ENGINEERING AND MECHANICAL ENGINEERING COLLEGE KUMAR TECHNOLOGY 11 HINDUSTHAN POLYTECHNIC Tamil Nadu S KARTHICK ENGINEERING AND MECHANICAL ENGINEERING COLLEGE TECHNOLOGY 12 HINDUSTHAN POLYTECHNIC Tamil Nadu S.H SAIRA BANU ENGINEERING AND First Year/Other COLLEGE TECHNOLOGY 13 HINDUSTHAN POLYTECHNIC Tamil Nadu K CHANDRAKAL ENGINEERING AND FIRST YEAR/OTHER COLLEGE A TECHNOLOGY 14 HINDUSTHAN POLYTECHNIC Tamil Nadu M XAVIER RAJ ENGINEERING AND ELECTRONICS & COMMUNICATION COLLEGE TECHNOLOGY ENGG 15 HINDUSTHAN POLYTECHNIC Tamil Nadu R SRI VIDHYA ENGINEERING AND FIRST YEAR/OTHER COLLEGE TECHNOLOGY 16 HOLYCROSS ENGINEERING Tamil Nadu J. VIGNESH ENGINEERING AND ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICS COLLEGE TECHNOLOGY ENGINEERING 17 HOLYCROSS ENGINEERING Tamil Nadu P. SENTHAMARA ENGINEERING AND ELECTRONICS & COMMUNICATION COLLEGE I TECHNOLOGY ENGG 18 HOLYCROSS ENGINEERING Tamil Nadu K. -

Sri Lanka: Tamil Politics and the Quest for a Political Solution

SRI LANKA: TAMIL POLITICS AND THE QUEST FOR A POLITICAL SOLUTION Asia Report N°239 – 20 November 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. TAMIL GRIEVANCES AND THE FAILURE OF POLITICAL RESPONSES ........ 2 A. CONTINUING GRIEVANCES ........................................................................................................... 2 B. NATION, HOMELAND, SEPARATISM ............................................................................................. 3 C. THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT AND AFTER ................................................................................ 4 D. LOWERING THE BAR .................................................................................................................... 5 III. POST-WAR TAMIL POLITICS UNDER TNA LEADERSHIP ................................. 6 A. RESURRECTING THE DEMOCRATIC TRADITION IN TAMIL POLITICS .............................................. 6 1. The TNA ..................................................................................................................................... 6 2. Pro-government Tamil parties ..................................................................................................... 8 B. TNA’S MODERATE APPROACH: YET TO BEAR FRUIT .................................................................. 8 1. Patience and compromise in negotiations -

Center for Peace & Reconciliation

CENTER FOR PEACE & RECONCILIATION 08, Grousseault Road Jaffna Sri Lanka Tel / Fax 021 222 8131 E mail: [email protected] Web site: www.peacecentrejaffna.lk STUDENTS COMMUNITY IN NORTH & EAST IS TERRIFIED Parts of Sri Lanka, namely North and East are becoming a deadly place for the students, teachers or education officials. Attacks on education often escape international attention amid the general fighting in conflict-affected countries. However, the number of reported assassinations and intimidation, bombings and burnings of school and academic staff and buildings has risen dramatically in the past three years, reflecting the increasingly bloody nature of local conflicts around Sri Lanka. I strongly suggest that the worst-affected Schools, Colleges, Universities and other academic Institutions that should be safe havens for children, have increasingly become the prime target of attacks by armed parties. The students in the North and East of Sri Lanka are highly at stake. The Government continues not only to be indifferent to establish security measures against the massive death threat mounting on the students community but also it promotes the underworld activities by using its collaborating paramilitary viz. EPDP and Karuna Faction. Systematic suppression of Judiciary and the law enforcement authorities; Geographical set up of Jaffna Peninsula, PTA, Emergency Regulation, Multi-presence of Military, infiltration of LTTE into Government controlled area, activities of the Paramilitary have been hampering the study programme of the students in North and East. This is a part of the package deal of the Government to suppress the study programme of the students in the North and East. In the LTTE controlled area, the students are terrorised by forcible recruitment, intimidation and restriction in freedom of movement and expression. -

Sri Lanka Tamil Separatism CPIN V6.0

Country Policy and Information Note Sri Lanka: Tamil Separatism Version 6.0 May 2020 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules • The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

Suicide Terrorism in Sri Lanka

AUGUST 2004 IPCS Research Papers SSuuiicciiddee TTeerrrroorriissmm iinn SSrrii LLaannkkaa R Ramasubramanian Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies New Delhi, INDIA © 2004, Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies (IPCS) The Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies is not responsible for the facts, views or opinion expressed by the author. The Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies (IPCS), established in August 1996, is an independent think tank devoted to research on peace and security from a South Asian perspective. Its aim is to develop a comprehensive and alternative framework for peace and security in the region catering to the changing demands of national, regional and global security. Address: B 7/3 Lower Ground Floor Safdarjung Enclave New Delhi 110029 INDIA Tel: 91-11-5100 1900, 5165 2556, 5165 2557, 5165 2558, 5165 2559 Fax: (91-11) 5165 2560 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ipcs.org ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My sincere thanks and deep sense of gratitude to Prof. P.R. Chari, for his valuable comments and Dr.Suba Chandran for his guidance and support rendered throughout the program. I thank all my colleagues and the staff at IPCS for their kind encouragement. I am obliged to my senior friends, Ms. Rajeshwari, IPCS and Mr. Hari Shankar, SARDI for their help in myriad ways. I owe a debt of gratitude to my Mother Smt.R. Meenakshi Ammal, my family members and the Almighty for their blessing at every stage of my career. R Ramasubramanian Suicide Terrorism in Sri Lanka It would elicit little debate that since the non- abandon West Bank and Gaza, and by Al violence protest movements of Mahatma Gandhi, Qaeda to pressurize the United States to Martin Luther King J., and Nelson Mandela, the withdraw from the Saudi Arabian acts of suicide bombings, more than any other single Peninsula.4 Before the early 1980s, suicide form of political protest, have left their greatest terrorism was rare but not unknown. -

The Onset of Genocide/Politicide: Considering External Variables

The onset of genocide/politicide: considering external variables. A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science of the College of Arts and Sciences by Erika Alejandra García González B.A., International Relations, ITESM, Campus Monterrey, 2005 July 2015 Committee Chair: Richard J. Harknett, Ph.D. i Abstract By using case-studies as method of analysis, the dissertation analyzes the impact external variables can have at the onset of genocide and politicides. While a majority of studies focus on internal conditions when analyzing these events, the basic premise of this dissertation states that to understand why genocide and politicide occur it is important to assess the role of external variables as well as the interaction between them and the internal variables. The dissertation builds upon Harff’s (2003) statistical model of genocide/politicide, which tested internal variables as predictors of genocide or politicide events. The model, however, misclassified 26% of the cases. The cases included in the dissertation, Iraq, Indonesia and East Timor, were selected because they have at least two events with one accurately predicted and another not predicted by Harff’s model. The dissertation used a modified version of Stoett’s (2004) classification of state involvement to assess the role of external variables at the onset of these crimes: effects of colonialism at state creation, direct assistance, and indirect support. By using case-studies it was possible to observe the interaction between the external and internal variables and how those dynamics worked at the onset of genocide and politicide, allowing to observe how external variables influenced, constituted and created the events and which ones had a larger impact. -

The Yale Review of International Studies

VOLUME 4, ISSUE 3, SPRING 2014 The Yale Review of International Studies The Acheson Prize Issue FIRST PLACE THIRD PLACE (TIED) The Historiography of Postwar The Invisible Ring and and Contemporary Histories the Invisible Contract: of the Outbreak of World War I Corporate Social Contract Tess McCann as the Normative Basis 91 of Corporate Environmental Responsibility SECOND PLACE Dilong Sun 57 Sinking Their Claws into the Arctic: Prospects for Four Ways to Matter in Sino-Russian Relations in the Pakistan: How Four of World’s Newest Frontier Pakistan’s Most Important TaoTao Holmes Politicians Retained Power 75 in Exile, 1984 – 2014 Akbar Ahmed 33 EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Samuel Obletz, Grayson Clary EXECUTIVE EDITOR Allison Lazarus MANAGING EDITORS Erwin Li, Talya Lockman-Fine SENIOR EDITORS Aaron Berman, Adrian Lo, Anna Meixler, Apsara Iyer, Jane Darby Menton EDITORS Abdul-Razak Zachariah, Andrew Tran, Elizabeth de Ubl, Miguel Gabriel Goncalves, Miranda Melcher DESIGN Martha Kang McGill and Grace Robinson-Leo CONTRIBUTORS Akbar Ahmed, Erin Alexander, TaoTao Holmes, Jack Linshi, Tess McCann, Dilong Sun ACADEMIC ADVISORS Paul Kennedy, CBE Amanda Behm J. Richardson Dilworth Associate Director, Professor of History, International Security Yale University Studies, Yale University Walter Russell Mead Beverly Gage James Clarke Chace Professor of History, Professor of Foreign Yale University Affairs, Bard College Nuno Monteiro Ambassador Ryan Crocker Assistant Professor Kissinger Senior Fellow, of Political Science, Jackson Institute, Yale Yale University -

Strained Fraternity

Strained Fraternity IDENTITY FORMATIONS, MIGRATION AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION AMONG SRI LANKAN TAMILS IN TAMIL NADU, INDIA NICOLAY PAUS THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE CAND.POLIT DEGREE DEPT. OF SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF BERGEN APRIL 2005 Acknowledgements This research could not have been conducted without the assistance and help of several people. I am primarily indebted to my dear friends in India and Sri Lanka who, in spite of their sense of insecurity, warmly received me and accepted me as a part of their lives. I also wish to thank Fr. Elias and other people from the Jesuit community in Tamil Nadu, Agnes Fernando, as well as the people at OfERR for helping me in the initial difficult stages of my fieldwork. Their help were of immense importance for me, and my research would have been much more difficult to carry out were it not for their assistance. Discussions with Manuelpillai Sooaipillai and Joseph Soosai were also helpful while preparing my journey to India. I also wish to stress my sincere gratitude to my supervisors during these years, Professor Leif Manger and Professor Bruce Kapferer. Their knowledge, feedbacks and advises have been highly appreciated. Furthermore, I wish to thank the Chr. Michelsen Institute where I have been affiliated as a student since February 2003. The academic environment and discussions with people at the institute has been very aspiring and helpful for my work. I am indebted to Marianne Longum Gauperaa for her great support before, during and after my fieldwork. Her own experiences and backing was of great help.