The Onset of Genocide/Politicide: Considering External Variables

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conserving the Past, Mobilizing the Indonesian Future Archaeological Sites, Regime Change and Heritage Politics in Indonesia in the 1950S

Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Vol. 167, no. 4 (2011), pp. 405-436 URL: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/btlv URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-101399 Copyright: content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License ISSN: 0006-2294 MARIEKE BLOEMBERGEN AND MARTIJN EICKHOFF Conserving the past, mobilizing the Indonesian future Archaeological sites, regime change and heritage politics in Indonesia in the 1950s Sites were not my problem1 On 20 December 1953, during a festive ceremony with more than a thousand spectators, and with hundreds of children waving their red and white flags, President Soekarno officially inaugurated the temple of Śiwa, the largest tem- ple of the immense Loro Jonggrang complex at Prambanan, near Yogyakarta. This ninth-century Hindu temple complex, which since 1991 has been listed as a world heritage site, was a professional archaeological reconstruction. The method employed for the reconstruction was anastylosis,2 however, when it came to the roof top, a bit of fantasy was also employed. For a long time the site had been not much more than a pile of stones. But now, to a new 1 The historian Sunario, a former Indonesian ambassador to England, in an interview with Jacques Leclerc on 23-10-1974, quoted in Leclerc 2000:43. 2 Anastylosis, first developed in Greece, proceeds on the principle that reconstruction is only possible with the use of original elements, which by three-dimensional deduction on the site have to be replaced in their original position. The Dutch East Indies’ Archaeological Service – which never employed the term – developed this method in an Asian setting by trial and error (for the first time systematically at Candi Panataran in 1917-1918). -

The Cultural Revolution and the Mao Personality Cult

Bard College Bard Digital Commons History - Master of Arts in Teaching Master of Arts in Teaching Spring 2018 'Long Live Chairman Mao!' The Cultural Revolution and the Mao Personality Cult Angelica Maldonado Bard College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/history_mat Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Chinese Studies Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Secondary Education Commons Recommended Citation Maldonado, Angelica, "'Long Live Chairman Mao!' The Cultural Revolution and the Mao Personality Cult" (2018). History - Master of Arts in Teaching. 1. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/history_mat/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Master of Arts in Teaching at Bard Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History - Master of Arts in Teaching by an authorized administrator of Bard Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ‘Long Live Chairman Mao!’ The Cultural Revolution and the Mao Personality Cult By Angelica Maldonado Bard Masters of Arts in Teaching Academic Research Project January 26, 2018 Maldonado 2 Table of Contents I. Synthesis Essay…………………………………………………………..3 II. Primary documents and headnotes……………………………………….28 a. Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung b. Chairman Mao badges c. Chairman Mao swims across the Yangzi d. Bombard the Headquarters e. Mao Pop Art III. Textbook critique…………………………………………………………33 IV. New textbook entry………………………………………………………37 V. Bibliography……………………………………………………………...40 Maldonado 3 "Had Mao died in 1956, his achievements would have been immortal. Had he died in 1966, he would still have been a great man. But he died in 1976. Alas, what can one say?"1 - Chen Yun Despite his celebrated status as a founding father, war hero, and poet, Mao Zedong is often placed within the pantheon of totalitarian leaders, amongst the ranks of Mussolini, Stalin, and Hitler. -

A Short History of Indonesia: the Unlikely Nation?

History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page i A SHORT HISTORY OF INDONESIA History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page ii Short History of Asia Series Series Editor: Milton Osborne Milton Osborne has had an association with the Asian region for over 40 years as an academic, public servant and independent writer. He is the author of eight books on Asian topics, including Southeast Asia: An Introductory History, first published in 1979 and now in its eighth edition, and, most recently, The Mekong: Turbulent Past, Uncertain Future, published in 2000. History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page iii A SHORT HISTORY OF INDONESIA THE UNLIKELY NATION? Colin Brown History Indonesia PAGES 13/2/03 8:28 AM Page iv First published in 2003 Copyright © Colin Brown 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. Allen & Unwin 83 Alexander Street Crows Nest NSW 2065 Australia Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100 Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218 Email: [email protected] Web: www.allenandunwin.com National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Brown, Colin, A short history of Indonesia : the unlikely nation? Bibliography. -

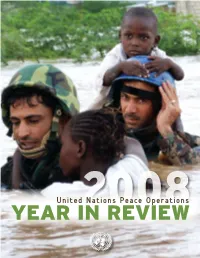

Year in Review 2008

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Politics & Society

Politics & Society http://pas.sagepub.com Armed Groups and Sexual Violence: When Is Wartime Rape Rare? Elisabeth Jean Wood Politics Society 2009; 37; 131 DOI: 10.1177/0032329208329755 The online version of this article can be found at: http://pas.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/37/1/131 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Politics & Society can be found at: Email Alerts: http://pas.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://pas.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://pas.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/37/1/131 Downloaded from http://pas.sagepub.com at AMERICAN UNIV LIBRARY on November 23, 2009 Armed Groups and Sexual Violence: When Is Wartime Rape Rare?* ELISABETH JEAN WOOD This article explores a particular pattern of wartime violence, the relative absence of sexual violence on the part of many armed groups. This neglected fact has important policy implications: If some groups do not engage in sexual vio- lence, then rape is not inevitable in war as is sometimes claimed, and there are stronger grounds for holding responsible those groups that do engage in sexual violence. After developing a theoretical framework for understanding the observed variation in wartime sexual violence, the article analyzes the puzzling absence of sexual violence on the part of the secessionist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam of Sri Lanka. Keywords: sexual violence; rape; political violence; human rights; war *This article is part of a special section of Politics & Society on the topic “patterns of wartime sexual violence.” The papers were presented at the workshop Sexual Violence during War held at Yale University in November 2007. -

Mobilization Chains Under Communist Rule — Comparing Regime Transitions in China and Poland

ASIEN 138 (Januar 2016), S. 126–148 Mobilization Chains under Communist Rule — Comparing Regime Transitions in China and Poland Ewelina Karas Summary This paper examines the impact of societal mobilization on regime transitions from Communism in China (between 1949 and 1989) and Poland (between 1945 and 1989) respectively. One of the main theoretical arguments put forward by this article is that of a dynamic model of dialectical interactions between a mobilizing society and a nondemocratic regime. I argue that China and Poland share a unique political culture in the form of a mobilizing society that is able to generate meaningful resistance even under highly repressive conditions. The second puzzle addressed in this paper is why, given their similar domestic environments, the Polish regime collapsed in 1989 whereas the one in China — despite facing intense mobilization in the same year — was able to survive. These differences in transition outcomes will be explained by a number of independent variables: different modes of regime establishment (authentic revolutionary in China versus imposed in Poland), elite and opposition attitudes to democracy, regime cross-case learning, economic development, and the role of the religion. Keywords: Regime transitions, societal challenge, post-Communism in Eastern Europe and China, social movements, authoritarianism Ewelina Karas is a Ph.D. student at the City University of Hong Kong. Mobilization Chains under Communist Rule 127 Introduction China and Poland once shared a common communist regime type, and furthermore have both faced repeated mass protests: in 1956, 1968, 1970, 1976, 1980, and 1988/89 in Poland (Kamiński 2009), and in 1976, 1978–79, 1986–87, and 1989 in China (Baum 1994, Goldman 2001, 2005;). -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Solidarnosc: Polish Company Union For·CIA and Bankers

A Spartacist Pamphlet $1.00 Solidarnosc: Polish Company Union for· CIA and Bankers -.~~, )(-523 Spartacist Publishing Co., Box 1377, GPO, New York, N.Y. 10116 2 Table of Contents Introduction As Lech Walesa struts before the ly progressive socialized property in Solidarnosc conference displaying his Poland, all the more so since the Madonna lapel pin and boasting how he discredited Stalinists manifestly cannot. Introduction ....... '..... , ...... 2 could easily have secured 90 percent of The call for "communist unity against the vote, the U.S. imperialists see their imperialism through political revolu Wall Street Journal Loves revanchist appetites for capitalist resto tion," first raised by the Spartacist Poland's Company Union .. 4 ration in Eastern Europe coming closer tendency at the time of the Sino-Soviet and closer to fruition. And the "crisis of split, acquires even greater urgency as Time Runs Out in Poland proletarian leadership" described by the Polish crisis underlines the need for Stop Solidarity's Trotsky Qearly a half-century ago is revolutionary unity of the Polish and Counterrevolution! ........... 7 starkly illuminated in the response of Russian workers to defeat U.S. imperi Walesa Brings "Mr. AFL-CIA" those in Poland and abroad who claim alism's bloody designs for bringing to Poland the right to lead the working class. Poland into the "free world" as a club I rving Brown: Stalinism has squandered the socialist against the USSR, military/industrial Cold War Criminal ..........13 and internationalist historic legacy of powerhouse of the deformed workers the Polish workers movement, demoral states. Solidarity Leaders Against izing the working class in the face of This pamphlet documents the Sparta Planned Economy resurgent Pilsudskiite reaction. -

The Communist Party Sweden

INTERNATIONAL GUESTS GREETING MESSAGES 18 TH CONGRESS OF THE COMMUNIST PARTY SWEDEN Guests and Greetings from Costa Rica, Cuba, Czech Republik, Denmark, El Salvador, France, Guatemala, Honduras, DPR Korea, Lao PDR, Norway, Palestine, Philippines, Poland, Schwitzerland, Spain, Sri Lanka, Syria, US, Venezuela, Vietnam and WFTU All international guests were welcome on stage at the first day of the congress. International guests and greeting messages The Communist Party, Sweden, has friends Cuba: Embassy of Cuba all over the world. It was clearly visible on Denmark : Danish Communist Party at the 18 th congress 5-7 th of January 2017 El Salvador : Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional (FMLN) with many international guests present and France : Pole of Communist Revival in France, many greeting messages sent to the con - PRCF gress. DPR Korea: Embassy of DPR Korea 13 international delegations attended the congress in Laos : Embassy of Lao PDR Göteborg. They were representing organizations in Palestine : Popular Front for the Liberation of twelve countries in Europe, Middle East, Asia and Palestine (PFLP) South and Central America. Philippines : National Democratic Front (NDF) Among the guests were Communists, anti-imperi - Sri Lanka : People's Liberation Front (JVP) alists and other forces that play a progressive role in Syria: Syrian Communist Party (United) their countries. Like British Trade Unionists Against UK : Trade Unionists Against the EU the EU which for decades has worked for Britain to Venezuela: Embassy of Bolivarian republic of leave the EU and in the referendum in June last year Venezuelan was on the winning side. In addition to organizations that the guests represent, The following international guests were present in the Communist Party received greetings from seve - the congress premises in Göteborg: ral organizations from all over the world. -

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized ...z w ~ ~ ~ w C ..... Z w ~ oQ. -'w >w Public Disclosure Authorized C -' -ct ou V') Public Disclosure Authorized " Public Disclosure Authorized VIOLENCE PREVENTION A Critical Dimension of Development Background 2 Agenda 4 Participant Biographies 10 Photo Contest Imagining Peace 32 Photo Contest Winners 33 Photo Contest Finalists 36 Conference Organizing Team & Contact Information 43 The Conflict, Crime and Violence team in the Social high levels of violent crime, street violence, do Development Department (SDV) has organized a mestic violence, and other kinds of violence. day and a half event focusing on "Violence Pre vention: A Critical Dimension of Development". Violence takes many forms: from the traditional As the issue of violence crosscuts other agendas protection racket by illegal organizations to the of the World Bank, the objectives of the event are rise of international illegal trafficking (arms, hu to raise World Bank staff's awareness of the link mans, drugs), from gang-based urban violence between violence prevention and development, its and crime to politically-motivated violence fueled relevance for development, and to present the ra by socio-economic grievances. All these forms of tionale for increased attention to violence preven violence concur to erode the well-being of all- and tion and reduction within World Bank operations. more acutely of the poorest - and to stymie devel opment efforts. Social failure, weak institutional Violence has become one of the most salient de capacity and the lack of a legal framework to pro velopmental issues in the global agenda. Its nega tect and guarantee people's safety and rights cre tive impact on social and economic development ate a climate of lawlessness and engender dynam in countries across the world has been well doc ics of state-within-state behavior by increasingly umented. -

Applying the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: a Case Study of Henry Kissinger

Applying the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court: A Case Study of Henry Kissinger Steven Feldsteint TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .......................................... 1665 I. Background ........... ....... ..................... 1671 A . H enry Kissinger ........................................................................ 1672 B. The Development of International Humanitarian Law ............. 1675 1. Sources of International Law ............................................. 1676 2. Historical Development of International Humanitarian L aw ..................................................................................... 16 7 7 3. Post-World War 11 Efforts to Codify International Hum anitarian Principles ................................................. 1680 a. The 1948 Genocide Convention ......................................... 1680 b. The Geneva Conventions ................................................... 1682 c. United Nations Suite of Human Rights Conventions ......... 1684 C. The Development of International War Crimes Tribunals ....... 1685 1. N urem berg Tribunal ........................................................... 1685 2. IC TY and IC TR .................................................................. 1687 3. The International Criminal Court ....................................... 1688 4. U niversal Jurisdiction ......................................................... 1694 5. A lien Tort Claim s A ct ........................................................ 1695 I1. Individual Accountability -

Rearticulations of Enmity and Belonging in Postwar Sri Lanka

BUDDHIST NATIONALISM AND CHRISTIAN EVANGELISM: REARTICULATIONS OF ENMITY AND BELONGING IN POSTWAR SRI LANKA by Neena Mahadev A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland October, 2013 © 2013 Neena Mahadev All Rights Reserved Abstract: Based on two years of fieldwork in Sri Lanka, this dissertation systematically examines the mutual skepticism that Buddhist nationalists and Christian evangelists express towards one another in the context of disputes over religious conversion. Focusing on the period from the mid-1990s until present, this ethnography elucidates the shifting politics of nationalist perception in Sri Lanka, and illustrates how Sinhala Buddhist populists have increasingly come to view conversion to Christianity as generating anti-national and anti-Buddhist subjects within the Sri Lankan citizenry. The author shows how the shift in the politics of identitarian perception has been contingent upon several critical events over the last decade: First, the death of a Buddhist monk, which Sinhala Buddhist populists have widely attributed to a broader Christian conspiracy to destroy Buddhism. Second, following the 2004 tsunami, massive influxes of humanitarian aid—most of which was secular, but some of which was connected to opportunistic efforts to evangelize—unsettled the lines between the interested religious charity and the disinterested secular giving. Third, the closure of 25 years of a brutal war between the Sri Lankan government forces and the ethnic minority insurgent group, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), has opened up a slew of humanitarian criticism from the international community, which Sinhala Buddhist populist activists surmise to be a product of Western, Christian, neo-colonial influences.