Scandinavia: an Example of the Chalk-Talk Method in Geography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Asians in Scandinavia: Diasporic Identity Processes Rashmi Singla Roskilde University, [email protected]

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Papers from the International Association for Cross- IACCP Cultural Psychology Conferences 2009 South Asians in Scandinavia: Diasporic Identity Processes Rashmi Singla Roskilde University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Singla, R. (2009). South Asians in Scandinavia: Diasporic identity processes. In G. Aikaterini & K. Mylonas (Eds.), Quod Erat Demonstrandum: From Herodotus’ ethnographic journeys to cross-cultural research: Proceedings from the 18th International Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers/39/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the IACCP at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers from the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology Conferences by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. South Asians in Scandinavia: Diasporic Identity Processes Rashmi Singla, Roskilde University, Denmark, [email protected] This chapter1 probes selected social-psychological aspects for South Asian young adults in Denmark and is a follow up of a Danish project conducted in the mid-nineties. The diasporic conceptualizations in respect to human centeredness and cultural processes in migration combined with life course perspective, provide the theoretical framework for this study. In-depth interviews were employed, and information was analyzed through meaning condensation and subsequent categorization of the narratives. The results show the reinterpretation of the self, “others” and home in the diasporic families, for the parental as well as the young generation. The chapter also depicts the young adults’ diasporic identities involving the ancestral countries as well as the Scandinavian welfare societies. -

Arctic Species Trend Index 2010

Arctic Species Trend Index 2010Tracking Trends in Arctic Wildlife CAFF CBMP Report No. 20 discover the arctic species trend index: www.asti.is ARCTIC COUNCIL Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Directorate for Nature Management, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • The Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment, the Environmental Agency, the Government of Greenland • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska CAFF Permanent Participant Organisations: • Aleut International Association (AIA) • Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) • Gwich’in Council International (GCI) • Inuit Circumpolar Conference (ICC) Greenland, Alaska and Canada • Russian Indigenous Peoples of the North (RAIPON) • The Saami Council This publication should be cited as: Louise McRae, Christoph Zöckler, Michael Gill, Jonathan Loh, Julia Latham, Nicola Harrison, Jenny Martin and Ben Collen. 2010. Arctic Species Trend Index 2010: Tracking Trends in Arctic Wildlife. CAFF CBMP Report No. 20, CAFF International Secretariat, Akureyri, Iceland. For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Website: www.caff.is Design & Layout: Lily Gontard Cover photo courtesy of Joelle Taillon. March 2010 ___ CAFF Designated Area Report Authors: Louise McRae, Christoph Zöckler, Michael Gill, Jonathan Loh, Julia Latham, Nicola Harrison, Jenny Martin and Ben Collen This report was commissioned by the Circumpolar Biodiversity Monitoring Program (CBMP) with funding provided by the Government of Canada. -

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

American-Scandinavian Foundation, Midwest Office Records, 1969-1974

American-Scandinavian Foundation, Midwest Office records, 1969-1974 Size: 16 linear feet (23 boxes) Acquisition: The collection was transferred from the Special Collections at the Augustana College library to the Swenson Center in 1981. Access: The collection is open for research and a limited amount of copies can be requested via mail. Processed by: Christina Johansson Control Num.: SSIRC I/O:12 Historical Sketch The American-Scandinavian Foundation was founded in 1910 by Danish-American industrialist and philanthropist Niels Poulsen. The ASF is a publicly supported non-profit organization and engages in educational exchange between the United States and Scandinavia. It offers extensive fellowships, grants and trainee placements, as well as publishes and supports cultural events. ASF's main office is located in New York City and it is governed by a Board of Trustees made up by individuals from Scandinavia and the United States. The organization has donors, alumni and members worldwide. Its publication, The American Scandinavian Review, has been published since 1913. In 1969, the foundation enlisted John Norton to set up a regional office at Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois. Norton coordinated trainee placements, built membership, and developed a regional cultural programming. He was also responsible for seeking funding for programs presented at Scandinavian-American institutions in the Midwest. After two years at Augustana College, the Midwest office moved to Augsburg College in Minneapolis. The office remained at Augsburg until the fall of 1972, and was closed when Norton moved back to Moline, Illinois to resume his career with Deere & Company. During 1969-1972, the Midwest chapter added more than 1,000 new members, primarily through membership incentives connected with group travel to Scandinavia. -

Multilingualism As a Cohesion Factor in the European Culture

MULTILINGUALISM AS A COHESION FACTOR IN THE EUROPEAN CULTURE 1. EUROPEAN LANGUAGES Many European languages have their origins in three Indo-European language groups: the Romance languages from the Latin of the Roman Empire; the Germanic languages, whose original language was spoken in Southern Scandinavia, and the Slavic languages, derived from the Protoslav branch, which existed for over 3000 years before evolving into a variety of other languages during the period between the VI-IX centuries AD1. In general, all the current languages in Europe settled during the Middle Ages. Until then, the various languages had evolved rapidly because there was only a small percentage of people who could read and write. With so few people being able to read, it was normal for languages to be passed from generation to generation orally, making its evolutional process more expedient than what it currently is today. Romance languages were, and still to this day are spoken mainly in Southwestern Europe and in Romania and Moldova (Spanish, French, Portuguese and Italian are Romance languages, as well as other languages that are not so widespread as Catalan or Sardinian). Germanic languages have their roots in Northern and Northwestern Europe, and in some areas of Central Europe; to this group belong German, Dutch, Danish, Norwegian, Swedish and Icelandic, as well as Frisian, which is considered a minority language. Slavic languages are spoken in Central Europe, the Balkans, Russia and West of Russia. Because the area suffered numerous invasions over several centuries, languages were strongly differentiated from each other, which is the reason for the current division into three distinct groups: Western, Eastern and Southern. -

Voyage Calendar

February 2016 March 2016 April 2016 May 2016 June 2016 July 2016 August 2016 September 2016 October 2016 November 2016 December 2016 January 2017 February 2017 March 2017 April 2017 May 2017 June & July 2017 Alluring Andes & Majestic Fjords Journey Through the Amazon Mayan Mystique Northwest Wonders Coastal Alaska Coastal Alaska Coastal Alaska Accent on Autumn Beacons of Beauty Celebrate the Sunshine Pacific Holidays Baja & The Riviera Amazon Exploration Patagonian Odyssey Southern Flair The Great Northwest Lima to Buenos Aires Rio de Janeiro to Miami Miami to Miami San Francisco to Vancouver Seattle to Seattle Seattle to Seattle Seattle to Seattle New York to Montreal New York to Montreal Miami to Miami Miami to Los Angeles Los Angeles to Los Angeles Miami to Rio de Janeiro Buenos Aires to Lima Miami to Miami San Francisco to Vancouver 21 days | February 7 22 days | March 11 10 days | April 2 10 days | May 10 7 days | June 9 7 days | July 8 7 days | August 4 12 days | September 18 10 days | October 12 12 days | November 5 16 days | December 22 10 days | January 7 23 days | February 2 22 days | March 7 10 days | April 14 11 days | May 10 Radiant Rhythms Atlantic Charms Majesty of Alaska Glacial Explorer Majestic Beauty Glaciers & Gardens Fall Medley Landmarks & Lighthouses Caribbean Charisma Panama Enchantment Ancient Legends Palms in Paradise Buenos Aires to Rio de Janeiro Miami to Miami Vancouver to Seattle Seattle to Seattle Seattle to Seattle Seattle to Vancouver Montreal to New York Montreal to Miami Miami to Miami Los Angeles to -

Storytelling in Western Europe and Scandinavia by Kristine Casper

Storytelling in Western Europe and Scandinavia By Kristine Casper Introduction Many geographers argue that Europe is not one of the major continents of the planet but part of a larger continent of Eurasia. Europe actually is a large peninsula off the western portion of Asia. Separated from the rest of Asia by the Ural Mountains in Russia to the East, and bordered on the West by the North Sea and Atlantic Oceans, Europe developed a rich cultural legacy of its own granting this land mass the designation of one of the seven continents of the world. For the purposes of this article, we are focusing on the countries of Western Europe. They are Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Germany, The Netherlands, Belgium, France, Andorra, Switzerland, and Austria. There are many similarities between these countries. Christianity in its various forms is the predominant religion in Western Europe setting them apart from some of the countries of Eastern Europe, explored in another chapter. Domestic life is very similar from country to country where the family is exclusively nuclear in type. Politically, the region is democratic and many of the independent countries are unifying themselves economically with the European Union allowing their people greater freedoms in work and tourism. Geographically, all but Andorra, Switzerland and Austria share a long coastline and enjoy the fishing and climate that bordering a large ocean brings to them. Moreover, recreationally, all of the countries count Football (American Soccer) as one of the most played and watched sports. However, even with these similarities, the countries of Western Europe have maintained independent cultures that are as varied as the people who populate the area. -

Scandinavia: Traits, Trends and Tensions

Knut Lundby,Pål Repstad Chapter 1 Scandinavia: Traits, Trends and Tensions Abstract: The Scandinavian welfaresocieties depend on strongstates to provide public services and to redistributeincome. Scandinavians enjoy comprehensive welfaresystems that offer citizens social security within open economies. Scan- dinavia combines international market capitalism with governmentregulation. The political–economic crisis in Europe influences Scandinavia as well, with pressurefrom globalization and immigration, and new political divisions that are articulated by right-wing populism. The Scandinavian countries are built on egalitarian values and practices and the level of trust between people is high. However,the countries are finding that these egalitarian values also have unintended, problematic consequences, espe- ciallyasthese once relativelyhomogenous societies experience growingdiversi- ty.Today, there are peculiar contrasts in the Scandinavian cultural–religious landscape, between old churches with large majorities of the population as members, and levels of secularity in Scandinavian societies that position the re- gion as the most secular corner of the world. Keywords: Scandinavia,welfare state, welfaresociety,homogeneity,equality The Scandinavian countries,Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, are known as wel- fare societies that are based on culturalhomogeneity and the ideals of social equality. Scandinavia, with its surveyable population of 21 million (2017), is small in scale, but it scores highonseveral indices of social and economic per- formance.¹ There is awidespread self-understanding of liberal open-minded- ness, and secularity is often taken for granted. Equalitybetween the sexes is a corevalue. Conflicts are usually handled in negotiationswithin aneo-corporatist system between strongstates and collective institutions, or in open public debate (Engelstad et al. 2017b; Hilson 2008). These conflict-solving mechanisms extend to the media system. -

Can't We All Be More Like Scandinavians?

Can’tWe All Be More Like Scandinavians? Asymmetric Growth and Institutions in an Interdependent World Daron Acemoglu James A. Robinson Thierry Verdier MIT Harvard Paris School of Economics April 2013. Abstract Because of their more limited inequality and more comprehensive social welfare systems, many perceive average welfare to be higher in Scandinavian societies than in the United States. Why then does the United States not adopt Scandinavian-style institutions? More generally, in an interdependent world, would we expect all countries to adopt the same institutions? To provide theoretical answers to this question, we develop a simple model of economic growth in a world in which all countries benefit and potentially contribute to advances in the world technology frontier. A greater gap of incomes between successful and unsuccessful entrepreneurs (thus greater inequality) increases entrepreneurial effort and hence a country’s contribution to the world technology frontier. We show that, under plausible assumptions, the world equilibrium is asymmetric: some countries will opt for a type of “cutthroat”capitalism that generates greater inequality and more innovation and will become the technology leaders, while others will free- ride on the cutthroat incentives of the leaders and choose a more “cuddly” form of capitalism. Paradoxically, those with cuddly reward structures, though poorer, may have higher welfare than cutthroat capitalists; but in the world equilibrium, it is not a best response for the cutthroat capitalists to switch to a more cuddly form of capitalism. We also show that domestic constraints from social democratic parties or unions may be beneficial for a country because they prevent cutthroat capitalism domestically, instead inducing other countries to play this role. -

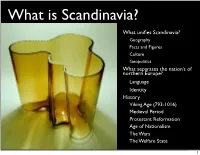

What Is Scandinavia?

What is Scandinavia? What unifies Scandinavia? Geography Facts and Figures Culture Geopolitics What separates the nation’s of northern Europe? Language Identity History Viking Age (793-1016) Medieval Period Protestant Reformation Age of Nationalism The Wars The Welfare State 1 Geography • Definining characteristics of Scandinavia’s location • Climate • Maritime access • Landmass • Forests • Not a “crossroads” • No Roman history Scandinavia on the northern margin of Europe, alongside Russia and Germany 2 Facts and Figures • Denmark • Norway • Copenhagen • Oslo • Danish • Trondheim • 5 million • Christiania • Finland • Norwegian • Helsinki • 4.5 million • Finnish/Swedish • Sweden • 5 million • Stockholm • Iceland • Göteborg • Reykjavik • Malmö • Icelandis • Swedish • 250,000 • 9 million 3 Culture • What do we mean by culture? • Organic implications • Culture as construct • “High Culture • “Anthropological culture” • Institutions as key construction sites • Unifying elements of Scandinavian culture • History • Not a part of Roman Empire • Vikings circa 800-1100 • Kalmar Union 1397-1512 • Language • Lutheran church • Constitutional Monarchies 13th-century Stavkirke, Norway • Universal welfare state 4 Geopolitics Finnish soldiers during the Continuation War, 1941-1944 • What is geopolitics? • Multiple causes for institutional (state) behavior • What relations of economics and geography together explain policy • Scandinavia on the Margins • Relatively limited sources of wealth • Small population dispersed over poor agricultural land • Location -

2 for 1 CRUISE FARES Plus FREE AIRFARE*

2 for 1 CRUISE FARES plus FREE AIRFARE* choose one: FREE - Shore Excursions FREE - Beverage Package FREE - Shipboard Credit plus: FREE - Unlimited Internet NEW $99 PREMIUM Arrive rested, refreshed and ready to explore on your own Oceania Cruises dream vacation. ECONOMY AIR UPGRADE* Enjoy wider seats, abundant leg room and a personal entertainment system at your disposal. CRUISE NAME FULL SPECIAL EMBARK & DISEMBARK PORTS OF CALL BROCHURE OFFER FARES SHIP | SAIL DATE | DAYS FARES FROM FROM BALTIC, SCANDINAVIA & NORTHERN EUROPE choose one: SCANDINAVIAN GLORY London (Southampton), UK; Vlissingen, Netherlands; Amsterdam, Netherlands; Kiel Canal Transit; FREE 4 Shore Excursions London to Copenhagen Stockholm, Sweden; Helsinki, Finland; St. Petersburg, Russia ; Tallinn, Estonia; Klaipeda, Lithuania; FREE Beverage Package $14,398 $5,799 Nautica | Jun 13, 2016 | 12 days Gdansk, Poland; Copenhagen, Denmark $400 Shipboard Credit choose one: REGAL ROUTES London (Southampton), UK; Paris (Le Havre), France; Bruges (Zeebrugge), Belgium; Antwerp, Belgium; FREE 4 Shore Excursions London to Copenhagen Amsterdam, Netherlands; Hamburg, Germany; Kristiansand, Norway; Oslo, Norway; FREE Beverage Package $9,998 $3,499 Marina | Jun 14, 2016 | 10 days Gothenburg, Sweden; Copenhagen, Denmark $400 Shipboard Credit choose one: FORTRESSES & FJORDS Copenhagen, Denmark; Ålesund, Norway; Trondheim, Norway; Hammerfest, Norway; Murmansk, Russia; Solovetsky Islands, Russia; Archangel, Russia; North Cape (Honningsvåg), Norway; Kristiansund, Norway; FREE 5 Shore Excursions -

BUSINESS PROFILE Name of Business: Brekke Tours, Inc., D.B.A

BUSINESS PROFILE Name of Business: Brekke Tours, Inc., d.b.a. Brekke Tours & Travel. Location: 802 North 43rd Street, Grand Forks, North Dakota 58203 Phone/Fax: 701-772-8999 or 800-437-5302 / Fax 701-780-9352 Website/Email: www.brekketours.com / [email protected] Owners: Arne Brekke, President Char Rustan Brekke, Director Date of Opening: 1956 Brekke Farm in Flåm, where it Number of Employees: Ten all began… Hours of Operation: 9:00 am – 5:00 pm CST Professional Memberships: BBB (Better Business Bureau), ASTA (American Society of Travel Agents), CLIA (Cruise Line International Association) Products and services: Brekke Tours functions as a tour operator and destination specialist to Scandinavia. We produce our own escorted tour packages, as well as heritage tours to Norway. Our tour packages are sold directly to the general public and also on a wholesale basis through travel agents. Customized itineraries are created for groups based on special requests from families, organizations and travel agents. Customized itineraries are also offered to individual travelers as well as tour packages, cruises, hotels, and car rentals. With extensive experience in group travel, knowledge of the Scandinavian people and contacts within the American ethnic market, Brekke Tours also shares their expertise in creating customized tour packages in the Midwest for Scandinavian and other customized groups. Special Dates for Brekke Tours: 1956 First package tour to Norway. 1967 Brekke Tours offers first charter flight from Fargo to Oslo. 1978 The former Grand Forks Airport building is purchased to serve as home of Brekke Travel. 1980 Brekke Travel, Inc. is formed.