41 Retelling the Story of Judah and Tamar in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parshat Hashavua Yeshivat Har Etzion PARASHAT HASHAVUA

Parshat HaShavua Yeshivat Har Etzion PARASHAT HASHAVUA PARASHAT VAYIGASH By Rav Yaakov Meidan These are the Names of the Children of Israel – Names and Numbers Our parasha contains the list of the seventy members of Yaakov's house who came to Egypt. The list is rife with difficulties. I) Chetzron and Chamul These two sons of Peretz son of Yehuda are mentioned among those who descended to Egypt during the years of famine. The commentaries have already raised the difficulties concerning the closeness of events in Yehuda's life, which take place during the twenty two years that elapse between the sale of Yosef and the descent of Yaakov's family to Egypt. It will be recalled that Joseph was seventeen at the time that he was sold, thirty at the time of his appointment as viceroy, and that a further seven years of plenty and two years of famine passed before the descent to Egypt. During the course of those twenty-two years, Yehuda married the daughter of Shua, and begat Er and Onan. These two sons consecutively married Tamar and then died. 'Many days passed' before Tamar was deemed able to marry Shela. In the meantime, Yehuda married Tamar and begat Peretz. Peretz himself grew up, married, and begat Chetzron and Chamul who were among those who descended to Egypt. In other words, during the course of twenty two years, three generations were born to Yehuda and came of age, not to mention the 'many days' that Tamar waited in vain for the levirate marriage to take place. -

Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: a Critical Evaluation of Two Translations

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.8, No.2, 2017 Mistranslations of the Prophets' Names in the Holy Quran: A Critical Evaluation of Two Translations Izzeddin M. I. Issa Dept. of English & Translation, Jadara University, PO box 733, Irbid, Jordan Abstract This study is devoted to discuss the renditions of the prophets' names in the Holy Quran due to the authority of the religious text where they reappear, the significance of the figures who carry them, the fact that they exist in many languages, and the fact that the Holy Quran addresses all mankind. The data are drawn from two translations of the Holy Quran by Ali (1964), and Al-Hilali and Khan (1993). It examines the renditions of the twenty five prophets' names with reference to translation strategies in this respect, showing that Ali confused the conveyance of six names whereas Al-Hilali and Khan confused the conveyance of four names. Discussion has been raised thereupon to present the correct rendition according to English dictionaries and encyclopedias in addition to versions of the Bible which add a historical perspective to the study. Keywords: Mistranslation, Prophets, Religious, Al-Hilali, Khan. 1. Introduction In Prophets’ names comprise a significant part of people's names which in turn constitutes a main subdivision of proper nouns which include in addition to people's names the names of countries, places, months, days, holidays etc. In terms of translation, many translators opt for transliterating proper names thinking that transliteration is a straightforward process depending on an idea deeply rooted in many people's minds that proper nouns are never translated or that the translation of proper names is as Vermes (2003:17) states "a simple automatic process of transference from one language to another." However, in the real world the issue is different viz. -

Tamar: Conscious Choices and Choosing One's Own Destiny

Tamar: Conscious Choices and Choosing One’s Own Destiny Parashat Vayeishev (Genesis 38: 1 – 30) Do you make conscious choices? One of our Torah heroines surely did. Tamar made a conscious choice following the deaths of her husband, Judah’s son Er, Judah’s next son Onan, and Judah’s wife Hirah. Tamar became a childless widow and it seemed as though Judah had no plan to allow his youngest son Shelah to marry Tamar, as biblical law mandated. Judah claimed that Shelah was too young and he could not risk losing another son. However, our heroine Tamar needed a child in order to claim a true stake in the household of Judah. So, she tricked her father-in-law Judah into sleeping with her during his bereavement. Posing as a harlot, Judah solicited Tamar’s services, willingly giving Tamar his signet seal, his cord and his staff, all of which clearly identified him when she would later proclaim Judah’s paternity for her twin sons Perez and Zerah. Not for love or for lust, but rather for a legacy into the future, Tamar made a conscious choice. She took initiative. She changed destiny. And, ironically, Judah admitted, “She is more in the right than I!” (Genesis 38:26) Judah had refused the rights of levirate marriage to Tamar. It all returns to making choices. Each woman on our sisterhood roster has made a conscious choice to join sisterhood. We are grateful to the women who choose to join sisterhood and our congregation, for choosing the path of leadership, and for sharing mitzvah time. -

And This Is the Blessing)

V'Zot HaBerachah (and this is the blessing) Moses views the Promised Land before he dies את־ And this is the blessing, in which blessed Moses, the man of Elohim ְ ו ז ֹאת Deuteronomy 33:1 Children of Israel before his death. C-MATS Question: What were the final words of Moses? These final words of Moses are a combination of blessing and prophecy, in which he blesses each tribe according to its national responsibilities and individual greatness. Moses' blessings were a continuation of Jacob's, as if to say that the tribes were blessed at the beginning of their national existence and again as they were about to begin life in Israel. Moses directed his blessings to each of the tribes individually, since the welfare of each tribe depended upon that of the others, and the collective welfare of the nation depended upon the success of them all (Pesikta). came from Sinai and from Seir He dawned on them; He shined forth from יהוה ,And he (Moses) said 2 Mount Paran and He came with ten thousands of holy ones: from His right hand went a fiery commandment for them. came to Israel from Seir and יהוה ?present the Torah to the Israelites יהוה Question: How did had offered the Torah to the descendants of יהוה Paran, which, as the Midrash records, recalls that Esau, who dwelled in Seir, and to the Ishmaelites, who dwelled in Paran, both of whom refused to accept the Torah because it prohibited their predilections to kill and steal. Then, accompanied by came and offered His fiery Torah to the Israelites, who יהוה ,some of His myriads of holy angels submitted themselves to His sovereignty and accepted His Torah without question or qualification. -

Is It Right for Christians to Use Birth Control?

Wordofhisgrace.org BBBible Q&AAA Q. Is it right for Christians to use birth control? A. First, what we mean in this answer by birth control is conception control or contraception. We are not here addressing abortion, which is another issue. Unfortunately, various churches and Christian writers express differing opinions on contraception or birth control, most of which do not fully express the biblical view. The Bible does not mention birth control as such. Therefore, we must look at the implications of what the Bible says on the subjects of children and mercy to find the biblical view of birth control. First, we must dispense with a Scripture that is often used to condemn birth control, but which really has little to do with the subject. It is Genesis 38:7-10: "And Er, Judah’s firstborn, was wicked in the sight of the Lord; and the Lord slew him. And Judah said unto Onan, Go in unto thy brother’s wife, and marry her, and raise up seed to thy brother. And Onan knew that the seed should not be his; and it came to pass, when he went in unto his brother’s wife, that he spilled it on the ground, lest that he should give seed to his brother. And the thing which he did displeased the Lord: wherefore he slew him also." In these verses, Onan uses a form of birth control called coitus interruptus. Because verse 10 says, "the thing which he did displeased the Lord: wherefore he slew him also," this Scripture is often pointed to as proving that God is displeased with birth control. -

1 the Story of Yehuda and Tamar by David Silverberg Towards The

The Story of Yehuda and Tamar By David Silverberg Towards the middle of Parashat Vayeshev we come upon one of the more perplexing episodes narrated in the Torah: the story of Yehuda, his three sons, and his daughter-in-law Tamar. The Torah (Bereishit, chapter 38) tells that Yehuda, the fourth son of Yaakov, begot three sons, named Er, Onan and Sheila. Er, the eldest son, married a woman named Tamar and died childless soon thereafter. Yehuda then instructed the second son, Onan, to marry his widowed sister-in-law, seemingly in fulfillment of the mitzva of yibum , or the levirate marriage, introduced much later in the Torah, in the Book of Devarim (25:5-10). This mitzva obligates one to marry his deceased brother's wife if the deceased bore her no children, and forbids the widow from marrying anyone else. (In practice, in such circumstances the brother performs a ceremony called chalitza absolving both the brother and the widow from this obligation.) Accordingly, Onan married Tamar, but he, too, died without children. Yehuda feared that his third son, Sheila, would suffer the same fate as his two older brothers, and therefore refused to allow his marriage to Tamar, despite the levirate obligation. Tamar, fearful that she would never bear children, posed as a prostitute and stood along the road as Yehuda traveled, so that he would hire her services and she would conceive from him. Yehuda indeed engaged in relations with Tamar, completely unaware of her identity, and gave her several personal items as collateral to be returned when he delivers payment. -

From the Rabbi

WINTER NOVEMBER 2017-FEBRUARY 2018 Chai Lights CONGREGATION BETH ISRAEL • BERKELEY From the Rabbi Questions & Answers: Halakha This year during our very joyous celebrations of Simchat Torah, we had the unique P.9-10 opportunity to honor some of our shul’s most devoted life-long learners: Bella Barany, Yaakov Harari, Jory Gessow, and Preston Grant. Each has exemplified an unrelenting Preston Grant has been an independ- Laws of Chanukah attachment to Torah learning and ex- ent learner of Tanach for many years. P.11-12 hibited their resolute commitment to If you visit his home office, you will mastering areas of Torah study. quickly be struck by various charts, hanging around the room, which out- In my eleven years at CBI, I can line the literary structure of several hardly identify a single class that was chapters and books of Tanach. This not attended by Bella Barany as well is in keeping with Preston’s deep in- as by Yaakov Harari. Bella, as some volvement in CBI’s class on Psalms Gan Shalom P.04 know, learns at CBI’s Beit Midrash on that took place in our community long a daily basis, sometimes with a study ago, as well as Preston’s critical in- New Members P.06-07 partner and sometimes on her own. volvement in helping to create and launch M. Victoria Sutton’s classes on CBI Classes P.14-15 Besides attending classes at CBI, it the books of Tanach. seems like Yaakov attends any Jew- Calendar P.16-18 ish-related lecture at UC Berkeley as On the Shabbat right after Simchat well as other local Jewish institutions. -

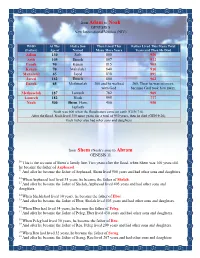

From Adam to Noah GENESIS 5 New International Version (NIV) Adam

from Adam to Noah GENESIS 5 New International Version (NIV) WHO At The Had a Son Then Lived This Father Lived This Many Total (Father) Age of Named Many More Years Years and Then He Died Adam 130 Seth 800 930 Seth 105 Enosh 807 912 Enosh 90 Kenan 815 905 Kenan 70 Mahalalel 840 910 Mahalalel 65 Jared 830 895 Jared 162 Enoch 800 962 Enoch 65 Methuselah 300 and he walked 365, Then he was no more, with God because God took him away. Methuselah 187 Lamech 782 969 Lamech 182 Noah 595 777 Noah 500 Shem, Ham, 450 950 Japheth Noah was 600 when the floodwaters came on earth (GEN 7:6). After the flood, Noah lived 350 more years, for a total of 950 years, then he died (GEN 9:28). Each father also had other sons and daughters from Shem (Noah’s son) to Abram GENESIS 11 10 This is the account of Shem’s family line. Two years after the flood, when Shem was 100 years old, he became the father of Arphaxad. 11 And after he became the father of Arphaxad, Shem lived 500 years and had other sons and daughters. 12 When Arphaxad had lived 35 years, he became the father of Shelah. 13 And after he became the father of Shelah, Arphaxad lived 403 years and had other sons and daughters. 14 When Shelah had lived 30 years, he became the father of Eber. 15 And after he became the father of Eber, Shelah lived 403 years and had other sons and daughters. -

Vayeshev – the Sins of Er and Onan (5778-2018) Rabbi Uriel Romano

Vayeshev – The Sins of Er and Onan (5778-2018) Rabbi Uriel Romano Yehuda had three children: Er, Onan and Shelah. According to the Torah, the first two sons did what was “evil in the eyes of the Lord” and for that reason they died. The Torah is explicit about the transgression of Onan: “Now Onan knew that the progeny would not be his, and it came about, when he came to his brother’s wife, he wasted [his semen] on the ground, in order not to give seed to his brother.” (Gen. 38:9) But what was Er’s transgression? The Torah is silent about it but the Midrash, quoted by Rashi, tells us that his transgression was the same as Onan’s: “Now, why should Er waste his semen? So that she (Tamar) would not become pregnant and her beauty be impaired.” (Yebamot 34b). Er and Onan sinned in the same way but with different purposes: the first did not want to make his wife pregnant so that she would not lose her beauty and the second did not want to have a child named after his deceased brother. In other words, the Sages want to tell us that “doing evil in the eyes of God” is often related to selfishness and pettiness. Er and Onan were punished for thinking only about themselves without thinking about others. While there is no certain and accurate criteria to be sure that our actions will find grace before God we can venture to say that if we act only on self interest to the detriment of others, surely those actions will not find favor in the eyes of God. -

Re-Examining the Levirate Marriage in the Bible Fung Tat Yeung a Thesis

Re-examining the Levirate Marriage in the Bible Fung Tat Yeung A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Divinity Graduate Division of Theology © The Chinese University of Hong Kong July 2008 The Chinese University of Hong Kong holds the copyright of this thesis. Any person(s) intending to use a part or whole of the materials in this thesis in a proposed publication must seek copyright released from the Dean of the Graduate School. IQj Abstract of Thesis entitled: Re-examining the Levirate Marriage in the Bible Submitted by Fung Tat Yeung For the degree of Master of Divinity at The Chinese University of Hong Kong in July 2008 Levirate marriage is probably one of the most incomprehensible biblical themes to nowadays' audience, who tends to consider it incestuous. In the Old Testament, Deuteronomy has enacted it as a law obliging a man to marry the childless widow of his deceased brother, and at the same time obliging a childless widow to be remarried inside her deceased husband's family. In the New Testament, the Sadducees and the Pharisees disagree with each other on the problem of a widow's remarriage. The Sadducees show that they are strict followers of the levirate law, but Paul the former Pharisee, in his Letter to the Romans, makes use of the illustration of a widow's freedom to marry another man to explain the significance of the release from the law. This shows that not all sects of Jews considered levirate marriage as an obligation for both the widow and the levir in the time of the New Testament. -

Using Scriptural Data to Calculate a Range-Qualified Chronology from Adam to Abraham

Using Scriptural Data to Calculate a Range-Qualified Chronology from Adam to Abraham With Comments on Why the "Open"-or-"Closed" Genealogy Question Is Chronometrically Irrelevant By: Thomas D. Ice, Th.M., Ph.D. Director, Pre-Trib Research Center Adjunct Professor, Tyndale Theological Seminary James J. Scofield Johnson, Th.D., D.C.Ed. Master Faculty, LeTourneau University Biblical Languages Instructor, Cross Timbers Institute Presented at the Southwest Regional Meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society at The Criswell College in Dallas, Texas on March 1, 2002. And God said, "Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days, and for years...." (Genesis 1:14) I. Introductory Overview God intended that His human creatures would be able to use the sun to calculate time on Earth, in years.1 The regular amount of time used when the Earth orbits around the sun is called a "year."2 Because earthly sun-orbits recur on a regular3 basis (and that is reliable and true because God made it to be so), years are a reliable and true time-unit for quantifying time on the Earth.4 The physical universe exists in space, time, and matter-energy (the latter category being a more technical name for "stuff"). God made time "in the beginning," at the same time when He made space and matter-energy. God works in time, not because He must but because He wanted to. God made mankind to live, on Earth, inside time (and space and stuff). -

Contraception and Sterilization Are They

CONTRACEPTION AND STERILIZATION: ARE THEY MORTAL SINS? St. Peter Catholic Church Faith Fact August 2014 Information compiled by Fr. Daniel Brouillette. ISSUE: Are contraception and sterilization always mortal sins? RESPONSE: The Catholic Church has always taught that contraception and sterilization are sinful and that those who engage in such practices with full knowledge and consent commit mortal sins, severing their relationships with Jesus Christ. DISCUSSION: Although the Catholic Church, through the Pope and the Magisterium, has been given the authority to “bind and loose” and to declare what is sinful, in reality that authority is only to speak for Christ, not to change what has already been divinely communicated. Unlike all of the other churches in existence, the Catholic Church has never changed a moral teaching. This extreme constancy of teaching makes the almost 2,000-year-old Catholic Church unique among institutions, offering strong evidence that it is divinely guided. Throughout the past twenty centuries, much has been said by this unique institution about the grave sinfulness of contraception and sterilization. 191 AD: Clement of Alexandria, The Instructor of Children “Because of its divine institution for the propagation of man, the seed is not to be vainly ejaculated, nor is it to be damaged, nor is it to be wasted” (2:10:91:2). 307 AD: Lactantius - Divine Institutes “[Some] complain of the scantiness of their means, and allege that they have not enough for bringing up more children, as though, in truth, their means were in [their] power…or God did not daily make the rich poor and the poor rich.