Inspiring the Next Generation of Polar Scientists: Classroom Extensions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report on 2014 Minister's Round Table on Parks Canada

Minister’s Round Table on Parks Canada 2 014 Building Urban to Arctic Connections INTRODUCTION On June 2, 2014, The Honourable Leona Aglukkaq, Participants in the MRT were asked to consider the Canada’s Minister of the Environment and Minister following questions: responsible for Parks Canada, hosted the seventh 1. How can we collectively increase Minister’s Round Table (MRT) on Parks Canada in visitation in Parks Canada places in the Ottawa, Ontario. This MRT, which focused on Canada’s North and provide a fuller experience of its North, included twenty stakeholders whose perspectives unique culture in ways that strengthen the represented a broad range of northern interests, such as traditional economy? tourism, education, arts and culture, conservation, and economic development, as well as representatives from 2. How can we collectively better connect Inuit and other Aboriginal organizations, other levels of urban Canadians with Parks Canada government, and the not-for-profit, public, and private places in the North? sectors. The MRT was structured as a one-day facili- Many ideas were put forward during the discussions. tated discussion designed to seek participants’ ideas The input of participants has been regrouped under and input on two topics related to the overarching theme three recommendations, which are detailed below, of “Building Urban to Arctic Connections.” along with Minister Aglukkaq’s responses to these The two discussion topics, “Connecting Urban recommendations. Canadians to Arctic places: Tourism and Traditional Economy,” and “Connecting the North to Urban Centres through Stories and Gateways,” reflect the intercon- nectedness of Parks Canada’s commitments to reaching Canadians where they live, work, and play and to celebrating the natural and cultural heritage of the North as an integral element of our national identity. -

07-08 November No. 2 Contents

THE ANTARCTICAN SOCIETY NEWSLETTER “BY AND FOR ALL ANTARCTICANS” VOL. 07-08 NOVEMBER NO. 2 CONTENTS PRESIDENT ANNOUNCEMENTS.............................cover SOUTH GEORGIA ASSOCIATION.................... 5 Dr. Arthur B. Ford 400 Ringwood Avenue BRASH ICE................................................. 1 BRITISH SEABED CLAIM................................... 5 Menlo Park, CA 94025 Phone: (650) 851-1532 SPEAKER FOR JOINT MEETING........... 2 JERRY KOOYMAN AWARD............................... 6 [email protected] SOUTH POLE DEDICATION.................. 2 PHYLACTERIES AT THE SOUTH POLE.......... 6 VICE PRESIDENT Robert B. Flint, Jr. CD ROM STILL AVAILABLE.................... 2 CAM CRADDOCK TRIBUTE.............................. 7 185 Bear Gulch Road Woodside, CA 94062 ANTARCTIC MUSIC................................ 3 I KNEW YOUR FATHER...................................... 8 Phone: (650) 851-1532 [email protected] Type to enter text CONVERSATION WITH AMUNDSEN............. 8 Type to enter text TREASURER Type to enter text Dr. Paul C. Dalrymple Box 325, Port Clyde, ME 04855 Phone: (207) 372-6523 [email protected] ANNOUNCEMENTS SECRETARY Charles Lagerbom YOU NOW HAVE A CHOICE, NEWSLETTER WILL BECOME AVAILABLE 83 Achorn Rd. Belfast, ME 04915 ELECTRONICALLY. Starting with our next issue, anticipated in late January 2008, you (207)548-0923 can pick up your Newsletter on our new web site which will be up and running the first of [email protected] the year, Members who choose to receive issues on the website will be given a password WEBMASTER -

ARCHIVED-CARN Vol 10, Spring 2000 [PDF-541.9

Vol. 10, Spring 2000 - C AR CR C A NEWSLETTER FOR THE C Canadian Antarctic Research Network Reckoning Lake Vostok Eddy Carmack1 and John Wüest2 Much like a fictional “Lost World” of childhood movies, Lake Vostok has until recently escaped man’s detection. Located in East Antarctica (Fig. 1), the 10- to 20- INSIDE million-year-old freshwater body is covered by a 3.7- to 4.2-km-thick layer of glacial ice. Lake Vostok is big: it has an area (~14,000 km2) near that of Lake Ladoga, a 3 Reckoning Lake Vostok 1 volume (~1,800 km ) near that of Lake Ontario, and a maximum depth (> 500 m) near that of Lake Tahoe. While the lake has yet to be penetrated, remote survey Skating on Thick Ice: methods suggest that it is filled with fresh water and that its floor is covered with An MP in Antarctica 3 thick sediments (Kapitsa et al., 1996). Letter from the Chair of CCAR 4 New analyses of Vostok ice core data reveal that microbes that have been Antarctic Ice Mass Change isolated for millions of years still live in and Crustal Motion 5 its waters and sediments (Vincent, 1999; Canadian Arctic–Antarctic Priscu et al., 1999; Karl et al., 1999). This Exchange Program 6 combination of thick ice cover and the Some Recent Canadian Contributions extreme isolation of its microbes makes to Antarctic and Bipolar Science 7 Vostok an excellent analog for planetary exploration (F. Carsey, pers. comm.). News in Brief 8 However, these extreme conditions call Studying Antarctic Diatoms 9 for the use of in situ micro-robotics specially designed to address an Letter from the CPC 10 anticipated range of physical and Information Update 11 geochemical conditions within the lake. -

Press Release

Press release Students from Nunavik, Canada and around the world embark onto Arctic Expedition from Kuujjuaq Nunavik August 6, 2010 Kuujjuaq, Quebec- Students on Ice Expeditions (SOI) and Makivik Corporation are delighted to announce and launch of the Arctic Expedition where eight Nunavik youth who have been selected from a pool of applications from across the region. The students who are aged from 14 to 19 will embark on a 2 week journey exploring northern Nunavik and the eastern Baffin Island of Nunavut. Before they board the ship a day event is planned beginning at the Kuujjuaq Katittavik Town Hall where there will be an inaugural launch with speakers, cultural entertainment followed by a BBQ and a town tour. This award winning organization, SOI, now in its 10th year of operation offers international, Canadian and Nunavik students unique educational expeditions to the Arctic and Antarctic. The goal is to provide students, educators and scientists inspiring educational opportunities at the ends of the Earth and, in doing so, help foster a new understaning and respect for the planet. Makivik Corporation and it’s subsidiary First Air who have been in partnership with SOI since 2007 is proud to introduce the eight youth from Nunavik who are sponsored for this expedition; Vicky Uqittuk of Kangiqsujuaq, Jimmy Angatuk & Daniel Cain Annahatak of Tasiujaq, Larissa Annahatak, Eva Saunders & Eva Angatuk from Kuujjuaq and Tamusi Kenuajuaq of Puvirnituq. Hannah Tooktoo of Kuujjuaq, will also be joining them, she is sponsored by the International Polar Year (IPY). They will go on board Cruise North’s vessel Lyubov Orlova with 71 other students. -

Strengthening Scientific Literacy on Polar Regions Through Education, Outreach and Communication (EOC)

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL & SCIENCE EDUCATION 2016, VOL. 11, NO. 12, 5498-5515 OPEN ACCESS Strengthening Scientific Literacy on Polar Regions Through Education, Outreach and Communication (EOC) Ahmad Firdaus Ahmad Shabudina, Rashidah Abdul Rahima, and Theam Foo Nga aUniversiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, MALAYSIA ABSTRACT In the 21st century, mankind must acknowledge the roles of polar regions in global sustainability, especially its interrelationship with Earth's climate system. Notably, dissemination of science knowledge and awareness that arises through education, outreach, and effective communication are key instruments that can help towards environmental conservation and sustainability on the polar regions. This paper aims to discover the science knowledge that has been derived about the polar regions and then to recommend the comprehensive approach for strengthening the Education, Outreach and Communication (EOC) strategy in promoting the polar regions. The fundamental scientific literacy on the polar regions can create a new understanding and respect towards the polar regions by mankind. Specifically, this would happen when a scientific perspective is brought into global problems that integrate socio-scientific issues (SSI) in science education and fostering science diplomacy and global common. Besides, it broadens the perspective about the earth as a global ecosystem. Therefore, a synergy framework of EOC is needed in a national polar programme to strengthen and sustain the public’s awareness and interest on the polar regions. Consequently, the information from this paper is important for policy makers and national polar governance in developing the future strategy of co- ordinating stakeholders and funds for EOC initiatives, especially during the Year of Polar Prediction (YOPP). -

CANADIAN ANTARCTIC BIBLIOGRAPHY, 2009–10* (Authors with Canadian Affiliations Are Underlined) Compiled by C

CANADIAN ANTARCTIC BIBLIOGRAPHY, 2009–10* (authors with Canadian affiliations are underlined) compiled by C. Simon L. Ommanney Canadian Committee on Antarctic Research, July 2010 Aguirre, G.E., M.P. Hernando, I.R. Schloss and G.A. Ferreyra. 2009. Indirect effects of temperature and ultraviolet radiation on grazing of the sub-Antarctic copepod Oithona similis. VII Jornadas Nacionales de Ciencias del Mar, 30 November – 4 December 2009, Bahía Blanca, Argentina. Mar del Plata, Asociación Argentina de Ciencias del Mar, presentation. Ainley, D.G. and L.K. Blight. 2009. Ecological repercussions of historical fish extraction from the Southern Ocean. Fish & Fish., 10(1), 13–38. Ainley, D. and 10 others!(including L.K. Blight). 2010. Impacts of cetaceans on the structure of Southern Ocean food webs. Mar. Mammal Sci., 26(2), 482–498. Aislabie, J. and J.M. Foght. 2009. Chapter 9. Response of polar soil bacterial communities to fuel spills. In Bej, A.K., J. Aislabie and R.M. Atlas, eds. Polar microbiology: the ecology, biodiversity and bioremediation potential of microorganisms in extremely cold environments. Boca Raton, FL, CRC Press; Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 215– 230. Aislabie, J., S. Jordan, J. Ayton, J.L. Klassen, G.M. Barker and S. Turner. 2009. Bacterial diversity associated with ornithogenic soil of the Ross Sea region, Antarctica. Can. J. Microbiol., 55(1), 21–36. Alexander, S.P. and M.G. Shepherd. 2010. Planetary wave activity in the polar lower stratosphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys. (ACP), 10(2), 707–718. Angiel, P.J., M. Potocki and J. Biszczuk-Jakubowska. 2010. Weather condition characteristics at the H. Arctowski Station (South Shetlands, Antarctica) for 2006, in comparison with multi-year research result. -

English Pages.Qxd Layout 1

Vol 27, November 2009 NEWSLETTER FOR THE Canadian Antarctic Research Network Inside Students on Ice: Antarctic Activities Students on Ice: Geoffrey D. Green Antarctic Activities 1 Students on Ice (SOI) is an award-winning organization offering unique educatio- Professors’ account of nal expeditions to the Antarctic and the Arctic. Its mandate is to provide students, Students on Ice IPY educators and scientists from around the world with inspiring educational oppor- Antarctic University Expedition 3 tunities at the ends of the Earth and, in doing so, help them foster a new under- standing and respect for the planet. Since the year 2000, Students on Ice has With the Students on Ice taken over 1200 students from more than 40 countries to both the polar regions. Antarctic University Expedition 6 SOI was proud to have its SOI–IPY Youth Expeditions 2007–2009 fully en- dorsed by the International Polar Year (IPY) Joint Committee as a prominent and Lazarev Sea Krill Survey (LAKRIS) 8 valued part of the current IPY. SOI’s expeditions and related educational activities represented one of the largest IPY outreach, training and communications events Antarctic Research at ISMER 8 in the world (Fig. 1). Now entering its tenth year, SOI has grown in scale, scope and depth. Since Update: Sander Geophysics conducting the first youth-specific expedition to Antarctica in the world, the orga- Explores the Antarctic 9 nization now leads 2–4 youth expeditions every year for both high-school and university students. Just one of the unique features of the program is how the Sedna IV Mission in the Western expeditions reach thousands via an exciting and educational expedition website, Antarctic Peninsula: allowing people from around the world to track the students on the expeditions First Results and share their personal growth and experiences. -

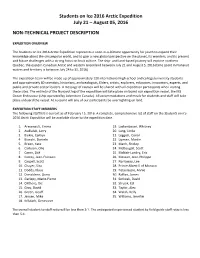

Students on Ice 2016 Arctic Expedition July 21 – August 05, 2016 NON-TECHNICAL PROJECT DESCRIPTION

Students on Ice 2016 Arctic Expedition July 21 – August 05, 2016 NON-TECHNICAL PROJECT DESCRIPTION EXPEDITION OVERVIEW The Students on Ice 2016 Arctic Expedition represents a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for youth to expand their knowledge about the circumpolar world, and to gain a new global perspective on the planet, its wonders, and its present and future challenges with a strong focus on Inuit culture. The ship- and land-based journey will explore northern Quebec, the eastern Canadian Arctic and western Greenland between July 21 and August 5, 2016 (time spent in Nunavut waters and territory is between July 24 to 31, 2016). The expedition team will be made up of approximately 120 international high-school and college/university students and approximately 80 scientists, historians, archaeologists, Elders, artists, explorers, educators, innovators, experts, and public and private sector leaders. A message of caution will be shared with all expedition participants when visiting these sites. The entirety of the Nunavut leg of the expedition will take place on board our expedition vessel, the MS Ocean Endeavour (ship operated by Adventure Canada). All accommodations and meals for students and staff will take place onboard the vessel. At no point will any of our participants be overnighting on land. EXPEDITION STAFF MEMBERS The following staff list is current as of February 15, 2016. A complete, comprehensive list of staff on the Students on Ice 2016 Arctic Expedition will be available closer to the expedition date. 1. Aresenault, Emma 19. Lackenbauer, Whitney 2. Audlaluk, Larry 20. Lang, Linda 3. Baikie, Caitlyn 21. Leggott, Conor 4. -

Investing in Students

STUDENTS ON ICE ARCTIC YOUTH EXPEDITION 2011 Iceland • Greenland • Labrador • Nunavik PROGRAM REPORT STUDENTS ON ICE STUDENTS ON ICE is an award-winning organization POLAR EDUCATION offering unique educational expeditions to the FOUNDATION Antarctic and the Arctic. Our mandate is to provide Natural Heritage Building students, educators and scientists from around the 1740 chemin Pink world with inspiring educational opportunities at the Gatineau, Québec J9J 3N7 ends of the Earth and, in doing so, help them foster a CANADA new understanding and respect for the planet. +1 819 827 3300 studentsonice.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. THANK YOU .................................................................... 2 2. STUDENT TESTIMONIALS ................................................. 3-4 3. SUMMARY OF THE EXPEDITION ..................................... 5-15 a) Educational Goals, Objectives and Format b) Expedition Itinerary c) Highlights, Challenges and Student Learning Outcomes 4. POLAR AMBASSADORS PROGRAM .................................. 16 5. MEDIA ............................................................................... 17 6. PARTNERS…….……………..………………………………... 18 Page 1 Dear Government of Nunavut – Department of Environment, The Students on Ice Arctic Youth Expedition 2011 was a tremendous success! The program and experiences shared over the two-week journey exceeded my every expectation. 74 students had life-changing experiences exploring Iceland, Greenland, Labrador, and Nunavik (Northern Québec) that will undoubtedly help to shape their perspectives and their futures. The highlights were abundant: meeting the President of Iceland, visiting glaciers, waterfalls and geysers, seeing polar bears in the wild, connecting with the natural world, learning from Inuit elders, fishing for Arctic char, Inuit throat singing and drum dancing, riding in a zodiac for the first time, making new friends, discussions with education team members and touching ice bergs were just some of the many highlights experienced by the inspiring youth on our team. -

Ipy-Jc-Summary-Appendices

Appendices Appendix 1: IPY Joint Committee Members Biographies Appendix 2: IPY Endorsed Projects as of May 2010 Appendix 3: IPY Joint Committee Meetings, 2005–2010 Appendix 4: IPY Proposal Evalution Form Used by the JC, 2005–2006 Appendix 5: Subcommittees Appendix 6: IPY Project Charts, 2005–2010 Appendix 7: List of the National IPY Committees Appendix 8: Ethical Principles for the Conduct of IPY Research Appendix 9: IPY Timeline 1997–2010 Appendix 10: Selection of IPY Logos Appendix 11: List of Acronyms a pp e n d ic e s 633 634 IPY 2007–2008 A PPEN D IX 1 IPY Joint Committee Members Biographies Invited Members Ian Allison (JC Co-Chair, 2004–2009) is a research scientist and leader of the Ice, Ocean, Atmosphere and Climate Program of the Australian Antarctic Division (retired). He has studied the Antarctic for over 40 years, participated in or led more than 25 research expeditions to the Antarctic, and published over 100 papers on Antarctic science. His research interests include the interaction of sea ice with the atmosphere and ocean; the dynamics and mass budget of the East Antarctic ice sheet; melt, freezing, and ocean circulation beneath floating ice shelves; and Antarctic weather and climate (Australian Antarctic Division and Antarctic Climate Ecosystems Cooperative Research Centre, Hobart, Australia). Michel Béland (JC Co-Chair, 2004–2010) is a meteorologist specializing in the field of atmospheric dynamics and numerical weather prediction. From January 1973 until his retirement in July 2008, he was with Environment Canada—first as a meteorologist, then as a research scientist in the field of predictability and global atmospheric modelling, and eventually as Director General, Atmospheric Science and Technology. -

Flag Report #19 Keough FINAL

FLAG EXPEDITION REPORT Flag Number 19 ANTARCTICA: Eye Witness Impact of Tourism 2014 compared to 1999 Submitted by ROSEMARIE KEOUGH JUNE 26, 2014 1 Flag Number: 19 Title of Expedition: ANTARCTICA: Eye Witness Impact of Tourism 2014 compared to 1999 Location of Expedition: 2014 Antarctic Peninsula and South Shetland Islands 1999 - 2001 Macquarie Island, South Sheltland Islands, South Orkney Islands, South Georgia. And in Antartica proper: Antarctic Peninsula, Queen Maud Land, Ellsworth Land, Berkner Island, Victoria Land, Ross Island and Ross Ice Shelf. Dates of Expedition: For the 2014 expedition, two voyages to the Antarctic were made between January 3rd and February 17th. For the two austral summers 1999-2000 and 2000-2001, consecutive Antarctica expeditions took place between first November through end March. WINGS Flag #19 was carried during the 2014 expedition. Expedition Participants: Rosemarie Keough – Leader, interviewer, photographer, researcher, reporting Pat Keough – photographer, supporter Expedition Sponsors and Funding: The 2014 expedition was opportunistic, piggy-backed upon a paid professional assigment. The Keoughs were engaged as lecturers aboard MS Seabourn Quest for two Antarctic voyages. While approval was received by Seabournʼs Antarctica Program Manager for Rosemarie Keough to conduct the WINGS expedition, Seabourn is not a participant in the information gathered by the Keoughs or the report prepared. All opinions are those expressed by the Keoughs and by the interviewees, speaking at arms length from Seabourn Cruise Line. The 1999 – 2001 expeditions were entirely financed by Nahanni Productions Inc., Rosemarie and Pat Keoughʼs photographic arts company. 2 Purpose of Expedition: The purpose of the 2014 Flag Expedition was for Rosemarie and Pat Keough to observe and record the impact of Antarctic tourism and make comparisions to their first-hand experiences of 1999 through 2001 when the couple spent two austral summers extensively exploring the Antarctic taking photographs for their tome ANTARCTICA. -

2016 Annual Report ››

›› 2016 ANNUAL REPORT thearticinstitute.org ›› ABOUT THE ARCTIC INSTITUTE Who We Are What We Do Established in 2011 and incorporated in 2015, The Arctic Institute’s mission is to help shape The Arctic Institute is an independent, nonprofit policy for a secure, just, and sustainable Arctic 501(c)3 tax-exempt organization headquartered through objective, multidisciplinary research in Washington, D.C with a network of of the highest caliber. Our research agenda researchers across the world. We envision a is constantly evolving to reflect a rapidly world in which the diverse and complex issues changing Arctic. Institute projects, publications, facing Arctic security are identified, understood, and events span the most pertinent security and innovatively resolved. Rigorous, qualitative, issues of the circumpolar region, developed and comprehensive research is the Institute’s by direct engagement and collaboration with core for developing solutions to challenges and young scholars, emerging regional actors, injustices in the circumpolar north. and northern communities. We provide data, analysis, and recommendations to policymakers, researchers, the media, and the interested public about circumpolar CREATIVITY. security challenges. Beyond our work, the INDEPENDENCE. Institute is building the future of Arctic research through partnerships with organizations across INNOVATION. the globe. OSLO COPENHAGEN LONDON BERLIN VANCOUVER TORONTO VIENNA BOSTON SAN FRANCISCO WASHINGTON DC Where We Are We are a think tank for the 21st Century. Our network of