Regulating the Desire Machine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

A Page 1 CART TITLE MANUFACTURER LABEL RARITY Atari Text

A CART TITLE MANUFACTURER LABEL RARITY 3D Tic-Tac Toe Atari Text 2 3D Tic-Tac Toe Sears Text 3 Action Pak Atari 6 Adventure Sears Text 3 Adventure Sears Picture 4 Adventures of Tron INTV White 3 Adventures of Tron M Network Black 3 Air Raid MenAvision 10 Air Raiders INTV White 3 Air Raiders M Network Black 2 Air Wolf Unknown Taiwan Cooper ? Air-Sea Battle Atari Text #02 3 Air-Sea Battle Atari Picture 2 Airlock Data Age Standard 3 Alien 20th Century Fox Standard 4 Alien Xante 10 Alpha Beam with Ernie Atari Children's 4 Arcade Golf Sears Text 3 Arcade Pinball Sears Text 3 Arcade Pinball Sears Picture 3 Armor Ambush INTV White 4 Armor Ambush M Network Black 3 Artillery Duel Xonox Standard 5 Artillery Duel/Chuck Norris Superkicks Xonox Double Ender 5 Artillery Duel/Ghost Master Xonox Double Ender 5 Artillery Duel/Spike's Peak Xonox Double Ender 6 Assault Bomb Standard 9 Asterix Atari 10 Asteroids Atari Silver 3 Asteroids Sears Text “66 Games” 2 Asteroids Sears Picture 2 Astro War Unknown Taiwan Cooper ? Astroblast Telegames Silver 3 Atari Video Cube Atari Silver 7 Atlantis Imagic Text 2 Atlantis Imagic Picture – Day Scene 2 Atlantis Imagic Blue 4 Atlantis II Imagic Picture – Night Scene 10 Page 1 B CART TITLE MANUFACTURER LABEL RARITY Bachelor Party Mystique Standard 5 Bachelor Party/Gigolo Playaround Standard 5 Bachelorette Party/Burning Desire Playaround Standard 5 Back to School Pak Atari 6 Backgammon Atari Text 2 Backgammon Sears Text 3 Bank Heist 20th Century Fox Standard 5 Barnstorming Activision Standard 2 Baseball Sears Text 49-75108 -

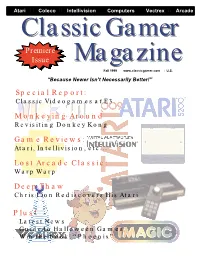

Premiere Issue Monkeying Around Game Reviews: Special Report

Atari Coleco Intellivision Computers Vectrex Arcade ClassicClassic GamerGamer Premiere Issue MagazineMagazine Fall 1999 www.classicgamer.com U.S. “Because Newer Isn’t Necessarily Better!” Special Report: Classic Videogames at E3 Monkeying Around Revisiting Donkey Kong Game Reviews: Atari, Intellivision, etc... Lost Arcade Classic: Warp Warp Deep Thaw Chris Lion Rediscovers His Atari Plus! · Latest News · Guide to Halloween Games · Win the book, “Phoenix” “As long as you enjoy the system you own and the software made for it, there’s no reason to mothball your equipment just because its manufacturer’s stock dropped.” - Arnie Katz, Editor of Electronic Games Magazine, 1984 Classic Gamer Magazine Fall 1999 3 Volume 1, Version 1.2 Fall 1999 PUBLISHER/EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Chris Cavanaugh - [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Sarah Thomas - [email protected] STAFF WRITERS Kyle Snyder- [email protected] Reset! 5 Chris Lion - [email protected] Patrick Wong - [email protected] Raves ‘N Rants — Letters from our readers 6 Darryl Guenther - [email protected] Mike Genova - [email protected] Classic Gamer Newswire — All the latest news 8 Damien Quicksilver [email protected] Frank Traut - [email protected] Lee Seitz - [email protected] Book Bytes - Joystick Nation 12 LAYOUT/DESIGN Classic Advertisement — Arcadia Supercharger 14 Chris Cavanaugh PHOTO CREDITS Atari 5200 15 Sarah Thomas - Staff Photographer Pong Machine scan (page 3) courtesy The “New” Classic Gamer — Opinion Column 16 Sean Kelly - Digital Press CD-ROM BIRA BIRA Photos courtesy Robert Batina Lost Arcade Classics — ”Warp Warp” 17 CONTACT INFORMATION Classic Gamer Magazine Focus on Intellivision Cartridge Reviews 18 7770 Regents Road #113-293 San Diego, Ca 92122 Doin’ The Donkey Kong — A closer look at our 20 e-mail: [email protected] on the web: favorite monkey http://www.classicgamer.com Atari 2600 Cartridge Reviews 23 SPECIAL THANKS To Sarah. -

Game Controls from Manual Company Note

Game Controls from manual Company Note AstroBlast left/right/fire M-Network Bump n Jump Left/Right/Up(speed up)/Down (slow down)/Fire (jump) M-Network Decathalon left/right (run)/fire (jump, throw, hurdle, put the shot or vault) Activision Beamrider left/right/fire laser/up (fire torpedoes) Activision Crackpots left/right/fire (drop pot) Activision Atlantis Left+fire/Right+fire/fire Imagic Demon Attack left/right/fire Imagic Shootin' Gallery Left/Right/fire Imagic Asteroids Counter clockwise/Clock wise/up (thrust)/down (hyperspace, shields, or flip)/fire Atari Big Bird's Egg Catch Left/Right Atari Frog Pond Left/Right/Fire (jump) Atari Galaxian Left/Right/Fire Atari Gravitar Left/Right/up (thrust)/down (tractor beam)/fire Atari Joust Left/Right/Fire Atari Klax Atari Midnight Magic Atari Moon Patrol Left/Right/Up (jump)/fire Atari Off the Wall Atari Pepsi Invaders Left/Right/Fire Atari Phoenix left/right/down (shield)/fire Atari Save Mary Left/Right/Fire (crane) Atari Skt Diver Left/Right/Down (open chute)/Fire (jump) Atari Slot Machine Atari Space Invaders Left/Right/Fire Atari Space War Counter clockwise/Clock wise/up (thrust)/down (hyperspace)/fire Atari Video Pinball Left/Right/ Up (both flippers)/Down (plunger)/Fire (release) Atari Carnival Left/Right/Fire Coleco Smurf Left/Right/Up (jump)/down (duck)/fire (new game) Coleco Deadly Duck Left/Right/Fire 20th Century Fox Worm War I Left/Right/Up(speed up)/Down (slow down)/Fire 20th Century Fox Star Trek Counter clockwise/Clock wise/up (thrust)/down (photons)/fire/Fire+Down (warp) Sega -

Dp Guide Lite Us

Atari 2600 USA Digital Press GB I GB I GB I 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe/Atari R2 Beat 'Em & Eat 'Em/Lady in Wadin R7 Chuck Norris Superkicks/Spike's Pe R7 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe/Sears R3 Berenstain Bears/Coleco R6 Circus/Sears R3 A Game of Concentration/Atari R3 Bermuda Triangle/Data Age R2 Circus Atari/Atari R1 Action Pak/Atari R6 Berzerk/Atari R1 Coconuts/Telesys R3 Adventure/Atari R1 Berzerk/Sears R3 Codebreaker/Atari R2 Adventure/Sears R3 Big Bird's Egg Catch/Atari R2 Codebreaker/Sears R3 Adventures of Tron/M Network R2 Blackjack/Atari R1 Color Bar Generator/Videosoft R9 Air Raid/Men-a-Vision R10 Blackjack/Sears R2 Combat/Atari R1 Air Raiders/M Network R2 Blue Print/CBS Games R3 Commando/Activision R3 Airlock/Data Age R2 BMX Airmaster/Atari R10 Commando Raid/US Games R3 Air-Sea Battle/Atari R1 BMX Airmaster/TNT Games R4 Communist Mutants From Space/St R3 Alien/20th Cent Fox R3 Bogey Blaster/Telegames R3 Condor Attack/Ultravision R8 Alpha Beam with Ernie/Atari R3 Boing!/First Star R7 Congo Bongo/Sega R2 Amidar/Parker Bros R2 Bowling/Atari R1 Cookie Monster Munch/Atari R2 Arcade Golf/Sears R3 Bowling/Sears R2 Copy Cart/Vidco R8 Arcade Pinball/Sears R3 Boxing/Activision R1 Cosmic Ark/Imagic R2 Armor Ambush/M Network R2 Brain Games/Atari R2 Cosmic Commuter/Activision R4 Artillery Duel/Xonox R6 Brain Games/Sears R3 Cosmic Corridor/Zimag R6 Artillery Duel/Chuck Norris SuperKi R4 Breakaway IV/Sears R3 Cosmic Creeps/Telesys R3 Artillery Duel/Ghost Manor/Xonox R7 Breakout/Atari R1 Cosmic Swarm/CommaVid -

Atari Giant Variation Label List (PDF)

Atari 2600 Label Variations This Atari 2600 label list is a compilation of input from many collectors in the field. A lot of hard work has been given by these collectors. You know who you are, and are too many to list. I thank you for everything you’ve done. Since this list is a joint effort, it will be available for all to use. It is a shame that when you input something, you are not fit to use it. So make a copy for yourself or ask me for one. I tell you to do this, so the list does not vanish in case something ever happens to me or my website. To update this list on my website, contact me at [email protected]. I will try and correct any mistakes and add any new info as I come across it. I’ve compiled a new and improved list from the one you’ve seen throughout the years. I’ve also made it much simpler to use. Any questions or comments, just contact me. I’m always on the Atari Age website as Philflound and that is also my AIM name. Rarity is going to be based on the label variation of the cartridge, not the game itself. There are many websites and guides that give the rarity of the carts, so it is just duplicate info you don’t need. I am giving rarity 3 grades along with a (?) grade. There may be more than one grade for variations. For example, Combat has 26 variations listed at this time. -

REPLY COMMENTSOF the MUSEUMOF ART and DIGITALENTERTAINMENT Item A. Commenter Information Museum of Art and Digital Entertainmen

REPLY COMMENTS OF THE MUSEUM OF ART AND DIGITAL ENTERTAINMENT Item A. Commenter Information Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment Represented by Alex Handy Samuelson Law, Technology & Public Policy Clinic 3400 Broadway Univ. of California, Berkeley, School of Law Oakland, CA 94611 Rob Walker (510) 282-4840 Brookes Degen [email protected] Michael Deamer 334 Boalt Hall, North Addition Berkeley, CA 94720 (510) 664-4875 [email protected] The Museum of Art and Digital Entertainment (the “MADE”) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization in Oakland, California dedicated to the preservation of video game history. The MADE supports the technical preservation of video games, presents exhibitions concerning historically significant games, and hosts lectures, tournaments, and community events. The MADE has personal knowledge and experience regarding this exemption through past participation in the sixth tri- ennial rulemaking relating to access controls on video games. The MADE is represented by the Samuelson Law, Technology & Public Policy Clinic at the Univer- sity of California, Berkeley, School of Law (“Samuelson Clinic”). The Samuelson Clinic is the lead- ing clinical program in technology and public interest law, dedicated to training law and graduate students in public interest work on emerging technologies, privacy, intellectual property, free speech, and other information policy issues. ITEM B. PROPOSED CLASS ADDRESSED Proposed Class 8: Computer Programs—Video Game Preservation ITEM C. OVERVIEW 1. Introduction From 1912 to -

You've Seen the Movie, Now Play The

“YOU’VE SEEN THE MOVIE, NOW PLAY THE VIDEO GAME”: RECODING THE CINEMATIC IN DIGITAL MEDIA AND VIRTUAL CULTURE Stefan Hall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Committee: Ronald Shields, Advisor Margaret M. Yacobucci Graduate Faculty Representative Donald Callen Lisa Alexander © 2011 Stefan Hall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ronald Shields, Advisor Although seen as an emergent area of study, the history of video games shows that the medium has had a longevity that speaks to its status as a major cultural force, not only within American society but also globally. Much of video game production has been influenced by cinema, and perhaps nowhere is this seen more directly than in the topic of games based on movies. Functioning as franchise expansion, spaces for play, and story development, film-to-game translations have been a significant component of video game titles since the early days of the medium. As the technological possibilities of hardware development continued in both the film and video game industries, issues of media convergence and divergence between film and video games have grown in importance. This dissertation looks at the ways that this connection was established and has changed by looking at the relationship between film and video games in terms of economics, aesthetics, and narrative. Beginning in the 1970s, or roughly at the time of the second generation of home gaming consoles, and continuing to the release of the most recent consoles in 2005, it traces major areas of intersection between films and video games by identifying key titles and companies to consider both how and why the prevalence of video games has happened and continues to grow in power. -

The Multiplayer Game: User Identity and the Meaning Of

THE MULTIPLAYER GAME: USER IDENTITY AND THE MEANING OF HOME VIDEO GAMES IN THE UNITED STATES, 1972-1994 by Kevin Donald Impellizeri A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Fall 2019 Copyright 2019 Kevin Donald Impellizeri All Rights Reserved THE MULTIPLAYER GAME: USER IDENTITY AND THE MEANING OF HOME VIDEO GAMES IN THE UNITED STATES, 1972-1994 by Kevin Donald Impellizeri Approved: ______________________________________________________ Alison M. Parker, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of History Approved: ______________________________________________________ John A. Pelesko, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: ______________________________________________________ Douglas J. Doren, Ph.D. Interim Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education and Dean of the Graduate College I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Katherine C. Grier, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation. I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Arwen P. Mohun, Ph.D. Member of dissertation committee I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: ______________________________________________________ Jonathan Russ, Ph.D. -

Atari 2600 Label Variations

Atari 2600 Label Variations This Atari 2600 label list is a compilation of input from many collectors in the field. A lot of hard work has been given by these collectors. You know who you are, and are too many to list. I thank you for everything you’ve done. Since this list is a joint effort, it will be available for all to use. It is a shame that when you input something, you are not fit to use it. So make a copy for yourself or ask me for one. I tell you to do this, so the list does not vanish in case something ever happens to me or my website. To update this list on my website, contact me at [email protected]. I will try and correct any mistakes and add any new info as I come across it. I’ve compiled a new and improved list from the one you’ve seen throughout the years. I’ve also made it much simpler to use. Any questions or comments, just contact me. I’m always on the Atari Age website as Philflound and that is also my AIM name. Rarity is going to be based on the label variation of the cartridge, not the game itself. There are many websites and guides that give the rarity of the carts, so it is just duplicate info you don’t need. I am giving rarity 3 grades along with a (?) grade. There may be more than one grade for variations. For example, Combat has 26 variations listed at this time. -

Revising the Atari Collection and Maintenance Policies Of

REVISING THE ATARI COLLECTION AND MAINTENANCE POLICIES OF THE WPI GORDON LIBRARY An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science SUBMITTED BY: SEAN WELCH PROJECT ADVISOR: DEAN O’DONNELL ABSTRACT In a world where games are becoming a larger influence in our lives the library needs an updated system for obtaining, cataloging, and loaning Atari gear. My goal on this project was to determine what our library had, needed, and what to preserve. I accomplished this by researching Atari’s history, appraisal sites, and consulting with the archivists about maintenance. I will conclude this project with instructions for future curators and a list of Atari items for the WPI Library. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Before we begin I would like to thank Professor Dean O’Donnell for making me aware of this project as well as our weekly meetings to discuss policy and potential research sources. I would also like to thank both Michael Kemezis and Jessica Colati for their advice on how to properly handle the Atari Equipment in the library and allowing me to take pictures for my IQP project. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. AUTHORSHIP PAGE Page 1 2. ABSTRACT Page 2 3. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Page 3 4. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 4 5. TABLE OF FIGURES Page 5 6. CHAPTER 1-INTRODUCTION Page 6 7. CHAPTER 2-RESEARCH PROCESS Page 8 8. CHAPTER 3-HISTORY OF ATARI Page 10 9. CHAPTER 4-CLEANING INSTRUCTIONS Page 15 10. CHAPTER 5-INTAKE RULES Page 17 11. -

Lista De Jogos Atari

ROM Numero Dip Switch 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (1978) (Atari) 0 000000000 Action Force - Action Man (1983) (Parker Bros) 1 000000001 Adventure (1978) (Atari) 2 000000010 Adventures of Tron (1983) (Mattel) 3 000000011 Air Raid 4 000000100 Air Raiders (1982) (Mattel) 5 000000101 Air-Sea Battle (1977) 6 000000110 Airlock (1982) (Data Age) 7 000000111 Alien (1982) (20th Century Fox) 8 000001000 Alien Invaders Plus (Space Invaders hack) 4k multicart 9 000001001 Alien Invaders Plus (Space Invaders hack) 10 000001010 Aligator People (20th Century Fox) (Prototype) 11 000001011 Amanda Invaders (PD) 12 000001100 Amidar (1983) (Parker Bros) 13 000001101 Armor Ambush (1982) (Mattel) 14 000001110 Assault (Bomb) 15 000001111 Astroblast (1982) (Mattel) 16 000010000 Astrowar (Starsoft) 17 000010001 Atari 2600 Invaders 18 000010010 Atari Invaders (Invaders Hack by Ataripoll) (PD) 19 000010011 Atari Video Cube (1982) (Atari) 20 000010100 Atlantis (Activision) 21 000010101 Atlantis II (1982) (Imagic) 22 000010110 Bachelor Party (Mystique) 23 000010111 Bachelorette Party (Mystique-Playaround) 24 000011000 Backgammon (1978) (Atari) 25 000011001 Bank Heist (1983) (20th Century Fox) 26 000011010 Barnstorming (1982) (Activision) 27 000011011 Basic Programming (1978) (Atari) 28 000011100 Basketball (1978) (Atari) 29 000011101 Beany Bopper (1982) (20th Century Fox) 30 000011110 Beast Invaders (double shot hack) 31 000011111 Beat 'Em and Eat 'Em (Mystique) 32 000100000 Bermuda Triangle (1982) (Data Age) 33 000100001 Berzerk (1982) (Atari) 34 000100010 Better Space Invaders