The Multiplayer Game: User Identity and the Meaning Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Introduction

Latest Gaming Console 1 1. INTRODUCTION Gaming consoles are one of the best digital entertainment media now available. Gaming consoles were designed for the sole purpose of playing electronic games. A gaming console is a highly specialised piece of hardware that has rapidly evolved since its inception incorporating all the latest advancements in processor technology, memory, graphics, and sound among others to give the gamer the ultimate gaming experience. A console is a command line interface where the personal computer game's settings and variables can be edited while the game is running. But a Gaming Console is an interactive entertainment computer or electronic device that produces a video display signal which can be used with a display device to display a video game. The term "video game console" is used to distinguish a machine designed for consumers to buy and use solely for playing video games from a personal computer, which has many other functions, or arcade machines, which are designed for businesses that buy and then charge others to play. 1.1. Why are games so popular? The answer to this question is to be found in real life. Essentially, most people spend much of their time playing games of some kind or another like making it through traffic lights before they turn red, attempting to catch the train or bus before it leaves, completing the crossword, or answering the questions correctly on Who Wants To Be A Millionaire before the contestants. Office politics forms a continuous, real-life strategy game which many people play, whether they want to or not, with player- definable goals such as ³increase salary to next level´, ³become the boss´, ³score points off a rival colleague and beat them to that promotion´ or ³get a better job elsewhere´. -

'Grand Theft Archive': a Quantitative Analysis of the State of Computer

Gooding, P. and Terras, M. (2008) "„Grand Theft Archive‟: a quantitative analysis of the current state of computer game preservation". The International Journal of Digital Curation. Issue 2, Volume 3, 2008. http://www.ijdc.net/ijdc/article/view/85/90 1 ‘Grand Theft Archive’: A Quantitative Analysis of the Current State of Computer Game Preservation Paul Gooding, Librarian, BBC Sports Library, London Melissa Terras, School of Library, Archive and Information Studies, University College London November 2008 Abstract Computer games, like other digital media, are extremely vulnerable to long-term loss, yet little work has been done to preserve them. As a result we are experiencing large-scale loss of the early years of gaming history. Computer games are an important part of modern popular culture, and yet are afforded little of the respect bestowed upon established media such as books, film, television and music. We must understand the reasons for the current lack of computer game preservation in order to devise strategies for the future. Computer game history is a difficult area to work in, because it is impossible to know what has been lost already, and early records are often incomplete. This paper uses the information that is available to analyse the current status of computer game preservation, specifically in the UK. It makes a quantitative analysis of the preservation status of computer games, and finds that games are already in a vulnerable state. It proposes that work should be done to compile accurate metadata on computer games and to analyse more closely the exact scale of data loss, while suggesting strategies to overcome the barriers that currently exist. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games ( Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack ( Arcade, TG16) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1943: Kai (TG16) 12. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 13. 1944: The Loop Master ( Arcade) 14. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 15. 19XX: The War Against Destiny ( Arcade) 16. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge ( Arcade) 17. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 18. 2020 Super Baseball ( Arcade, SNES) 19. 21-Emon (TG16) 20. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 21. 3 Count Bout ( Arcade) 22. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 23. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 24. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 25. 3-D WorldRunner (NES) 26. 3D Asteroids (Atari 7800) 27. -

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

Video Games and the Mobilization of Anxiety and Desire

PLAYING THE CRISIS: VIDEO GAMES AND THE MOBILIZATION OF ANXIETY AND DESIRE BY ROBERT MEJIA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communications in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Kent A. Ono, Chair Professor John Nerone Professor Clifford Christians Professor Robert A. Brookey, Northern Illinois University ABSTRACT This is a critical cultural and political economic analysis of the video game as an engine of global anxiety and desire. Attempting to move beyond conventional studies of the video game as a thing-in-itself, relatively self-contained as a textual, ludic, or even technological (in the narrow sense of the word) phenomenon, I propose that gaming has come to operate as an epistemological imperative that extends beyond the site of gaming in itself. Play and pleasure have come to affect sites of culture and the structural formation of various populations beyond those conceived of as belonging to conventional gaming populations: the workplace, consumer experiences, education, warfare, and even the practice of politics itself, amongst other domains. Indeed, the central claim of this dissertation is that the video game operates with the same political and cultural gravity as that ascribed to the prison by Michel Foucault. That is, just as the prison operated as the discursive site wherein the disciplinary imaginary was honed, so too does digital play operate as that discursive site wherein the ludic imperative has emerged. To make this claim, I have had to move beyond the conventional theoretical frameworks utilized in the analysis of video games. -

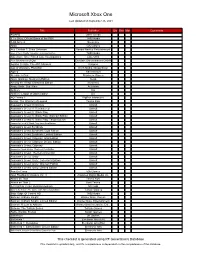

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

Gamasutra - Features - the History of Activision 10/13/11 3:13 PM

Gamasutra - Features - The History Of Activision 10/13/11 3:13 PM The History Of Activision By Jeffrey Fleming The Memo When David Crane joined Atari in 1977, the company was maturing from a feisty Silicon Valley start-up to a mass-market entertainment company. “Nolan Bushnell had recently sold to Warner but he was still around offering creative guidance. Most of the drug culture was a thing of the past and the days of hot-tubbing in the office were over,” Crane recalled. The sale to Warner Communications had given Atari the much-needed financial stability required to push into the home market with its new VCS console. Despite an uncertain start, the VCS soon became a retail sensation, bringing in hundreds of millions in profits for Atari. “It was a great place to work because we were creating cutting-edge home video games, and helping to define a new industry,” Crane remembered. “But it wasn’t all roses as the California culture of creativity was being pushed out in favor of traditional corporate structure,” Crane noted. Bushnell clashed with Warner’s board of directors and in 1978 he was forced out of the company that he had founded. To replace Bushnell, Warner installed former Burlington executive Ray Kassar as the company’s new CEO, a man who had little in common with the creative programmers at Atari. “In spite of Warner’s management, Atari was still doing very well financially, and middle management made promises of profit sharing and other bonuses. Unfortunately, when it came time to distribute these windfalls, senior management denied ever making such promises,” Crane remembered. -

Tények, Érdekességek Az Informatika Világából

Vers BASIC-nyelven aWikipédiából Kása Zoltán Tények, érdekességek az informatika világából Videójáték-konzolok (forrás: http://hu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Videojáték-konzolok_listája) Első generáció (1972–1977): Név Megjelenés Gyártó Típus Magnavox/Philips 1972/76 Magnavox/Philips konzol Odyssey Ping-o-Tronic 1974 Zanussi/Sèleco dedikált Atari/Sears Tele-Games 1975 Atari dedikált Pong Magnavox Odyssey 100 1975 Magnavox dedikált Magnavox/Philips 1975 Magnavox/Philips dedikált Odyssey 200 Magnavox Odyssey 300 1976 Magnavox dedikált Magnavox Odyssey 400 1976 Magnavox dedikált Magnavox Odyssey 500 1976 Magnavox dedikált Coleco Telstar 1976 Coleco dedikált APF TV Fun 1976 APF dedikált Radio Shack TV 1976 RadioShack dedikált Scoreboard Magnavox Odyssey 2000 1977 Magnavox dedikált Magnavox Odyssey 3000 1977 Magnavox dedikált Magnavox Odyssey 1977 Magnavox/Philips dedikált 4000/Philips Odyssey 2001 Binatone TV Master Mk IV 1977 Binatone dedikált 2013-2014/3 23 Play-o-Tronic 1977 Zanussi/Sèleco dedikált Color TV Game 6 (csak 1977 Nintendo dedikált Japánban) Philips Odyssey 2100 1978 Magnavox/Philips dedikált Video Pinball 1978 Atari dedikált Color TV Game 15 (csak 1978 Nintendo dedikált Japánban) Color TV Racing 112 (csak 1978 Nintendo dedikált Japánban) Color TV Game Block 1979 Nintendo dedikált Breaker (csak Japánban) Computer TV Game (csak 1980 Nintendo dedikált Japánban) BSS 01 (csak az NDK-ban) 1980 Kombinat dedikált Mikroelektronik Erfurt Második generáció (1976–1984): Név Megjelenés Gyártó Típus Fairchild Channel F/Video 1976 Fairchild konzol -

Finding Aid to the Atari Coin-Op Division Corporate Records, 1969-2002

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Atari Coin-Op Division Corporate Records Finding Aid to the Atari Coin-Op Division Corporate Records, 1969-2002 Summary Information Title: Atari Coin-Op Division corporate records Creator: Atari, Inc. coin-operated games division (primary) ID: 114.6238 Date: 1969-2002 (inclusive); 1974-1998 (bulk) Extent: 600 linear feet (physical); 18.8 GB (digital) Language: The materials in this collection are primarily in English, although there a few instances of Japanese. Abstract: The Atari Coin-Op records comprise 600 linear feet of game design documents, memos, focus group reports, market research reports, marketing materials, arcade cabinet drawings, schematics, artwork, photographs, videos, and publication material. Much of the material is oversized. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open for research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Though intellectual property rights (including, but not limited to any copyright, trademark, and associated rights therein) have not been transferred, The Strong has permission to make copies in all media for museum, educational, and research purposes. Conditions Governing Access: At this time, audiovisual and digital files in this collection are limited to on-site researchers only. It is possible that certain formats may be inaccessible or restricted. Custodial History: The Atari Coin-Op Division corporate records were acquired by The Strong in June 2014 from Scott Evans. The records were accessioned by The Strong under Object ID 114.6238. -

I\ATARI Power Without the Prie'"

SOFTT'IABE CATA1OGTJE FOR ATARI 8.BIT PERSONAL COMPUTER SYSTEMS 400 / wo / &0xL / 800x1/ I 30xE /I\ATARI Power Without the Prie'" ISSUE II _SEPTEMBER ]985 This cotologue contoins o selection of the best softwore ovoiloble for your Atori Personol Computer System. Soflwore is ovoiloble on either cossette or disk formot (certoin titles ore ovoiloble on bothl), ond selected titles ore ovoiloble on ROM cortridge. CONTACT... Your locol Atori deoler should be oble to help you select the softwo re for your requirements. lf you ore unoble io obtoin o softwore title in this cotologue, or would like detoils of your locol Atori deoler, conioct your neorest regionol Atori supplier: SILICON CENTRE LENDAC DATA SYSTEMS SILICA SHOP 7 Antiguo Slreet Unit 31 1-4 The Mews Edinburgh IDA Enterprise Centre Hothedey Rood &:otlond EN I 3NH Peo rse Streel Sidcu p (031) 557 4546 Dublin 2 Kent lrelond (0r) ELTEC 309 lrl (Dublin) 710226 Compus Rood THOMPSON COOK Lister Hills kience ATARI Hening Rood Pork PO Box 555 Woshford Brodford Slough Redditch Yorkshire BD7 1HR Berks SL2 5BZ Worcester BGB ODH (0274) 722512 (0753) 33344 (0s27) 25000 THERE'S MORE. A complete ronge of peripherols, books, mogozines ond other occessories ore ovoiloble for your Atorr personol Computer. Contoct your locol Atori deoler for detoils. CHECK! Before purchosing ony soflwore or hordwore, ensure lhot it is desrgned to work with your Alori computer model. Prod6ed by ATART (UK) pO CORp LID, BOX 555, SIOJGH, BERKS. SL2 5M otNEIAl. rtral{AoEmE1{I, INTEGIATED PACXAOES ETC. BUSTNESS Advmrure lnre.notlonol C.R.t.S. -

A Page 1 CART TITLE MANUFACTURER LABEL RARITY Atari Text

A CART TITLE MANUFACTURER LABEL RARITY 3D Tic-Tac Toe Atari Text 2 3D Tic-Tac Toe Sears Text 3 Action Pak Atari 6 Adventure Sears Text 3 Adventure Sears Picture 4 Adventures of Tron INTV White 3 Adventures of Tron M Network Black 3 Air Raid MenAvision 10 Air Raiders INTV White 3 Air Raiders M Network Black 2 Air Wolf Unknown Taiwan Cooper ? Air-Sea Battle Atari Text #02 3 Air-Sea Battle Atari Picture 2 Airlock Data Age Standard 3 Alien 20th Century Fox Standard 4 Alien Xante 10 Alpha Beam with Ernie Atari Children's 4 Arcade Golf Sears Text 3 Arcade Pinball Sears Text 3 Arcade Pinball Sears Picture 3 Armor Ambush INTV White 4 Armor Ambush M Network Black 3 Artillery Duel Xonox Standard 5 Artillery Duel/Chuck Norris Superkicks Xonox Double Ender 5 Artillery Duel/Ghost Master Xonox Double Ender 5 Artillery Duel/Spike's Peak Xonox Double Ender 6 Assault Bomb Standard 9 Asterix Atari 10 Asteroids Atari Silver 3 Asteroids Sears Text “66 Games” 2 Asteroids Sears Picture 2 Astro War Unknown Taiwan Cooper ? Astroblast Telegames Silver 3 Atari Video Cube Atari Silver 7 Atlantis Imagic Text 2 Atlantis Imagic Picture – Day Scene 2 Atlantis Imagic Blue 4 Atlantis II Imagic Picture – Night Scene 10 Page 1 B CART TITLE MANUFACTURER LABEL RARITY Bachelor Party Mystique Standard 5 Bachelor Party/Gigolo Playaround Standard 5 Bachelorette Party/Burning Desire Playaround Standard 5 Back to School Pak Atari 6 Backgammon Atari Text 2 Backgammon Sears Text 3 Bank Heist 20th Century Fox Standard 5 Barnstorming Activision Standard 2 Baseball Sears Text 49-75108