Bipartisanship and Bicameralism: a New Inside View of Congressional Committees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Effects of Bicameralism on U.S. Appropriations Policies

THE EFFECTS OF BICAMERALISM ON U.S. APPROPRIATIONS POLICIES by MARK EDWARD OWENS (Under the Direction of Jamie L. Carson) ABSTRACT This dissertation examines how supermajority rules interact with other institutional constraints. I study appropriations policies to better understand how the content of legislation develops in response to bicameral differences over a one-hundred and four year period. As each chamber has developed independently of one another, the institutional differences that have emerged have had a dynamic impact on the lawmaking process. The time frame of the study, 1880 to 1984, is particularly important because it captures the years when the Senate grew to play a more active role in the legislative process and a number of key budgetary reforms. To study this phenomenon empirically, I measure how regular appropriations bills were packaged differently by the House and Senate from 1880 to 1984 and compare the final enactment to the difference in chamber proposals to determine the magnitude of a chamber’s leverage on enacted policy changes. By treating the Senate’s choice to amend the House version as a selection effect, we can examine the effect bicameralism has on policy outcomes. Specifically, I analyze a ratio that represents how close the final bill is to the Senate version, given the size of the bicameral distance. Finally, I complete the study by examining how the president influences bicameral negotiations and how bicameralism complicates our theories of intra-branch relations. INDEX WORDS: Appropriations, Bicameralism, Budgeting, Polarization, Senate THE EFFECTS OF BICAMERALISM ON U.S. APPROPRIATIONS POLICIES by MARK EDWARD OWENS B.A., University of Florida, 2006 M.A., Johns Hopkins University, 2008 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ATHENS, GEORGIA 2014 © 2014 Mark Edward Owens All Rights Reserved THE EFFECTS OF BICAMERALISM ON U.S. -

Management Challenges at the Centre of Government: Coalition Situations and Government Transitions

SIGMA Papers No. 22 Management Challenges at the Centre of Government: OECD Coalition Situations and Government Transitions https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kml614vl4wh-en Unclassified CCET/SIGMA/PUMA(98)1 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques OLIS : 10-Feb-1998 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Dist. : 11-Feb-1998 __________________________________________________________________________________________ Or. Eng. SUPPORT FOR IMPROVEMENT IN GOVERNANCE AND MANAGEMENT IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES (SIGMA) A JOINT INITIATIVE OF THE OECD/CCET AND EC/PHARE Unclassified CCET/SIGMA/PUMA Cancels & replaces the same document: distributed 26-Jan-1998 ( 98 ) 1 MANAGEMENT CHALLENGES AT THE CENTRE OF GOVERNMENT: COALITION SITUATIONS AND GOVERNMENT TRANSITIONS SIGMA PAPERS: No. 22 Or. En 61747 g . Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format CCET/SIGMA/PUMA(98)1 THE SIGMA PROGRAMME SIGMA — Support for Improvement in Governance and Management in Central and Eastern European Countries — is a joint initiative of the OECD Centre for Co-operation with the Economies in Transition and the European Union’s Phare Programme. The initiative supports public administration reform efforts in thirteen countries in transition, and is financed mostly by Phare. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development is an intergovernmental organisation of 29 democracies with advanced market economies. The Centre channels the Organisation’s advice and assistance over a wide range of economic issues to reforming countries in Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Phare provides grant financing to support its partner countries in Central and Eastern Europe to the stage where they are ready to assume the obligations of membership of the European Union. -

Comparing the Dynamics of Party Leadership Survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard

This is a repository copy of Comparing the dynamics of party leadership survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/82697/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Heppell, T and Bennister, M (2015) Comparing the dynamics of party leadership survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard. Government and Opposition, FirstV. 1 - 26. ISSN 1477-7053 https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2014.31 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Comparing the Dynamics of Party Leadership Survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard Abstract This article examines the interaction between the respective party structures of the Australian Labor Party and the British Labour Party as a means of assessing the strategic options facing aspiring challengers for the party leadership. -

108Th Congress 229

PENNSYLVANIA 108th Congress 229 House of Representatives, 1972–96, serving as chairman of Appropriations Committee, 1989– 96, and of Labor Relations Committee, 1981–88; married: the former Virginia M. Pratt in 1961; children: Karen, Carol, and Daniel; elected to the 105th Congress; reelected to each succeeding Congress. Office Listings http://www.house.gov/pitts 204 Cannon House Office Building, Washington, DC 20515 .................................... (202) 225–2411 Chief of Staff.—Gabe Neville. Legislative Director.—Ken Miller. Press Secretary.—Derek Karchner. P.O. Box 837, Unionville, PA 19375 ........................................................................... (610) 444–4581 Counties: LANCASTER, BERK (part). CITIES AND TOWNSHIPS: Reading, Bern, Lower Heidelberg, South Heidelberg, Spring. BOROUGH OF: Wernersville. CHESTER COUNTY (part). CITIES AND TOWNSHIPS: Birmingham, East Bradford, East Fallowfield, East Marlborough, East Nottingham, Elk, Franklin, Highland, Kennett, London Britain, London Grove, Londonderry, Lower Oxford, New Garden, New London, Newlin, Penn, Pennsbury, Upper Oxford, West Fallowfield, West Marlborough, West Nottingham. BOROUGHS OF: Avondale, Kennett Square, Oxford, Parkesburg, West Chester, and West Grove. Population (2000), 630,730. ZIP Codes: 17501–09, 17512, 17516–22, 17527–29, 17532–38, 17540, 17543, 17545, 17547, 17549–52, 17554–55, 17557, 17560, 17562–70, 17572–73, 17575–76, 17578–85, 17601–08, 19106, 19310–11, 19317–20, 19330, 19342, 19346– 48, 19350–52, 19357, 19360, 19362–63, 19365, 19374–75, 19380–83, 19390, 19395, 19464, 19501, 19540, 19543, 19565, 19601–02, 19604–05, 19608–11 *** SEVENTEENTH DISTRICT TIM HOLDEN, Democrat, of St. Clair, PA; born in Pottsville, PA, on March 5, 1957; edu- cation: attended St. Clair High School, St. Clair; Fork Union Military Academy; University of Richmond, Richmond, VA; B.A., Bloomsburg State College, 1980; sheriff of Schuylkill County, PA, 1985–93; licensed insurance broker and real estate agent, John J. -

No. Coa19-384 Tenth District North Carolina Court Of

NO. COA19-384 TENTH DISTRICT NORTH CAROLINA COURT OF APPEALS ******************************************** NORTH CAROLINA STATE CONFERENCE OF THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. TIMOTHY K. MOORE, in his official capacity as SPEAKER OF THE NORTH CAROLINA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES; PHILIP E. BERGER, in his official capacity as PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE NORTH CAROLINA SENATE, Defendants-Appellants. ************************************************************* MOTION BY THE NORTH CAROLINA LEGISLATIVE BLACK CAUCUS FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE ************************************************************* ROBERT E. HARRINGTON ADAM K. DOERR ERIK R. ZIMMERMAN TRAVIS S. HINMAN ROBINSON, BRADSHAW & HINSON, P.A. 101 N. Tryon St., Suite 1900 Charlotte, NC 28246 (704) 377-2536 TO THE HONORABLE COURT OF APPEALS OF NORTH CAROLINA: The North Carolina Legislative Black Caucus (the “Caucus”) respectfully moves this Honorable Court for leave to file the attached brief amicus curiae in support of Plaintiff North Carolina State Conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (“NAACP”). Pursuant to North Carolina Rule of Appellate Procedure 28(i), the Caucus sets forth here the nature of its interests, the issues of law its brief will address, its positions on those issues, and the reasons why it believes that an amicus curiae brief is desirable. NATURE OF THE AMICUS’S INTEREST The Caucus is an association of 37 North Carolina State Senators and Representatives of African American, American Indian, and Asian-American Indian heritage. It is a vehicle designed to exercise unified political power for the betterment of people of color in North Carolina and, consequently, all North Carolinians; to ensure that the views and concerns of African Americans and communities of color more broadly are heard and acted on by elected representatives; and to further develop the political consciousness of citizens of all communities and cultures. -

Global TB Caucus Strategic Plan 2017-2020 DRAFT

Global TB Caucus Strategic Plan 2017-2020 DRAFT 1 Table of CContentsontents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................. 3 Vision, Mission and Values ....................................................................................................... 4 Our structure ........................................................................................................................... 4 History ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Why this strategy and why now? .............................................................................................. 7 The Global TB Caucus in 2020 ................................................................................................... 8 From centrally directed to locally led ...................................................................................... 13 Greater reach and a stronger network .................................................................................... 16 Shaping the international agenda ........................................................................................... 19 Organisational objectives: New funding for old problems ....................................................... 21 Organisational objectives: Better policies and better programmes .......................................... 24 Potential Funding and Policy Targets ..................................................................................... -

Gender-Sensitizing Commonwealth Parliaments

Gender-Sensitizing Commonwealth Parliaments The Report of a Commonwealth Parliamentary Association Study Group Gender-Sensitizing Commonwealth Parliaments The Report of a Commonwealth Parliamentary Association Study Group Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 27 February – 1 March 2001 Published by the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association Secretariat Suite 700, Westminster House, 7 Millbank London SW1P 3JA, United Kingdom This publication is also available online at www.cpahq.org Foreword Without doubt, more and more countries and Parliaments are appreciating that women have a right to participate in political structures and legislative decision-making. However, for the most part, although women may overcome the more general obstacles to their participation in Parliaments, once they reach there they often encounter additional difficulties. In 1998 the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) collaborated with three Commonwealth legal NGOs in the development of the Latimer House Guidelines on Parliamentary Supremacy and Judicial Independence. Among many other matters, the guidelines point out the need to improve the numbers of women Members in Commonwealth Parliaments and suggest ways in which this goal can be achieved. An earlier CPA study had already identified barriers to the participation of women in public life. The next logical step was to endeavour to identify means by which the task facing women Parliamentarians can be rationalized. Against this background, in February and March 2001 the CPA, with the assistance of the CPA Malaysia Branch and the approval of the CPA Executive Committee, arranged a Study Group in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, on Gender-Sensitizing Commonwealth Parliaments. The aims of the Study Group were set out as: 1. To share analyses, experiences and good practices of Standing Orders in Commonwealth Parliaments; 2. -

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Legislative

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA LEGISLATIVE JOURNAL MONDAY, OCTOBER 15, 2018 SESSION OF 2018 202D OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY No. 44 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES O divine Master, grant that I may not so much seek to be consoled as to console, The House convened at 11 a.m., e.d.t. to be understood as to understand, to be loved as to love. THE SPEAKER (MIKE TURZAI) For it is in giving that we receive, PRESIDING it is in pardoning that we are pardoned, and it is in dying that we are born to eternal life. MOMENT OF SILENCE In Your name we pray. Amen. FOR HON. MICHAEL H. O'BRIEN The SPEAKER. We were of course deeply saddened to learn PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE of the passing of our friend and colleague, Representative (The Pledge of Allegiance was recited by members and Michael O'Brien. So I would ask everybody to please stand as visitors.) able for a moment of silence as we reflect upon his life and legacy as a public servant. Of course we will be having a memorial at a later date and time. JOURNAL APPROVAL POSTPONED The prayer today will be offered by our friend and colleague, the minority whip, Representative Mike Hanna. Immediately The SPEAKER. Without objection, the approval of the thereafter we will recite the Pledge of Allegiance. Please stand Journal of Thursday, October 11, 2018, will be postponed until for this moment of silence, and then we will have Representative printed. Hanna give the prayer. BILL REPORTED FROM COMMITTEE, (Whereupon, the members of the House and all visitors stood CONSIDERED FIRST TIME, AND TABLED in a moment of silence in solemn respect to the memory of the Honorable Michael H. -

Race Redistricting, and the Congressional Black Caucus--Who Needs Em'!?: Gauging the Essentiality of African American Congresspersons Tara N

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Honors Theses University Honors Program 5-1996 Race Redistricting, and the Congressional Black Caucus--Who Needs Em'!?: Gauging the Essentiality of African American Congresspersons Tara N. Gillespie Southern Illinois University Carbondale Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/uhp_theses Recommended Citation Gillespie, Tara N., "Race Redistricting, and the Congressional Black Caucus--Who Needs Em'!?: Gauging the Essentiality of African American Congresspersons" (1996). Honors Theses. Paper 52. This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I Congressional Black Caucus 1 I I I I Race Redistricting, and the Congressional Black Caucus I Who Needs Em'!?: Gauging the Essentiality of African American Congresspersons I Tara N. Gillespie Spring 1996 I Southern Illinois University at Carbondale I I I I I I I I I I I I I I Congressional Black Caucus 2 I Abstract I In light of the recent controversy surrounding the validity of race conscious redistricting, the practice of creating congressional districts with an African I American or Hispanic majority population, an important question arises; are the votes of African American congresspersons even critical to the passage of policy I issues salient to the African American populace. This study seeks to prove that the votes of African American congresspersons are crucial to the passage of House I policy issues salient to the African American community. -

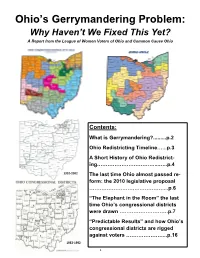

Ohio's Gerrymandering Problem

Ohio’s Gerrymandering Problem: Why Haven’t We Fixed This Yet? A Report from the League of Women Voters of Ohio and Common Cause Ohio Contents: What is Gerrymandering?.........p.2 Ohio Redistricting Timeline…...p.3 A Short History of Ohio Redistrict- ing……………………………...…..p.4 1992-2002 The last time Ohio almost passed re- form: the 2010 legislative proposal ……………………….……………...p.6 “The Elephant in the Room” the last time Ohio’s congressional districts were drawn ……………………….p.7 “Predictable Results” and how Ohio’s congressional districts are rigged against voters …………………...p.16 1982-1992 1 What is Gerrymandering? Redistricting 101: Why do we redraw districts? • Every ten years the US Census is conducted to measure population changes. • The US Supreme Court has said all legislative districts should have roughly the same population so that everyone’s vote counts equally. This is commonly referred to as “one person, one vote.” • In the year following the Census, districts are redrawn to account for people moving into or out of an area and adjusted so that districts again have equal population and, for US House districts, may change depending on the number of districts Ohio is entitled to have. • While the total number of state general assembly districts is fixed -- 99 Ohio House and 33 Ohio Senate districts -- the number of US House districts allocated to each state may change follow- ing the US Census depending on that state’s proportion of the total US population. For example, following the 2010 Census, Ohio lost two US House seats, going from 18 US House seats in 2002-2012 to 16 seats in 2012-2022. -

Official Programme

PROGRAMME CPA UK & PAKISTAN WOMEN’S PARLIAMENTARY CAUCUS WORKSHOP BUILDING SKILLS FOR WOMEN PARLIAMENTARIANS 25 - 27 MAY 2021 CPA UK Westminster Hall, London, United Kingdom SW1A OAA T: +44 (0) 207219 5373 E: [email protected] 1 CONTENTS WELCOME MESSAGE 1 IMPACT, OUTCOME & OUTPUTS 2 DELEGATE LIST 3 PROGRAMME 5 SPEAKER BIOGRAPHIES 7 CPA UK STAFF 9 ABOUT CPA UK 10 WELCOME MESSAGE On behalf of CPA UK I am delighted to welcome you to this virtual workshop for the Pakistan Women’s Parliamentary Caucus. This three-day programme has been designed to give you a chance to improve your skills and knowledge related to committee business in the National Assembly of Pakistan and the UK Parliament. There will be opportunity to hear from speakers in Pakistan and across the UK on a range of topics including writing effective committee recommendations and creating an effective relationship with government. This programme has been designed for newly elected women parliamentarians in Pakistan to develop their understanding of parliamentary procedure and act as a forum for sharing learning between Federal and Provincial members in Pakistan. As well as a time for learning from each other this programme is also a chance for delegates to deepen their knowledge of specific areas, such as gender-sensitive scrutiny of legislation. We encourage you to share your views and ask questions as freely and fully as possible. Thank you for taking the decision to participate in this programme. I hope you will find it a valuable, interesting and worthwhile experience. Jon Davies Chief Executive, CPA UK 1 GENERAL INFORMATION Programme Attendance Participants are expected to attend all sessions of the programme. -

Brief of Alabama Legislative Black Caucus and Alabama Association of Black County Officials, As Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents

No. 12-96 ================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- --------------------------------- SHELBY COUNTY, Alabama, Petitioner, v. ERIC H. HOLDER, Jr., Attorney General, et al., Respondents. --------------------------------- --------------------------------- On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The District Of Columbia --------------------------------- --------------------------------- BRIEF OF ALABAMA LEGISLATIVE BLACK CAUCUS AND ALABAMA ASSOCIATION OF BLACK COUNTY OFFICIALS, AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS --------------------------------- --------------------------------- JAMES U. BLACKSHER Counsel of Record P.O. Box 636 Birmingham, Alabama 35201 (205) 591-7238 [email protected] ================================================================ COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO. (800) 225-6964 OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................. ii INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE.......................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .............................. 2 ARGUMENT ........................................................ 3 I. For the First Time in History, in 2006 African-American Representatives from All Nine Covered Southern States Partic- ipated in Passage of a Voting Rights Act, and the Product of Their Negotiations Is Entitled to Great Respect .......................... 3 II. The Historical Context of This Case Weighs Heavily in Favor of Rejecting