Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/166705 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-29 and may be subject to change. Epic Architecture: Architectural Terminology and the Cities of Bethlehem and Jerusalem in the Epics of Juvencus and Proba* Roald DIJKSTRA Soon after Constantine’s seizure of power, splen- pear as classical as possible while treating biblical did basilicas were built in Rome and the Holy content, he omitted many references to Jewish Land.1 Constantine had created the conditions culture, including topographical details.4 He necessary for the emergence of a rich Christian was anxious not to alienate his Rome-oriented architecture. At the same time, Christian po- audience in a poem that was a daunting liter- etry now also fully emerged. The first classiciz- ary innovation. Words referring to the world of ing yet openly Christian poets – Juvencus and architecture, however, are certainly not absent Proba – took the Roman epic tradition and in from his epic.5 Most of them can be explained particular Vergil as their main literary examples. by remarks in the biblical text of the gospels: In this tradition – and also in Rome’s national they either denote (groups of) dwellings, graves, epic the Aeneid – monuments played an impor- ‘spiritual’ buildings outside the world of earthly tant role.2 Moreover, the Aeneid ultimately told realia, or function as building metaphors. the story of the foundation of Rome. -

SEDULIUS, the PASCHAL SONG and HYMNS Writings from the Greco-Roman World

SEDULIUS, THE PASCHAL SONG AND HYMNS Writings from the Greco-Roman World David Konstan and Johan C. ! om, General Editors Editorial Board Brian E. Daley Erich S. Gruen Wendy Mayer Margaret M. Mitchell Teresa Morgan Ilaria L. E. Ramelli Michael J. Roberts Karin Schlapbach James C. VanderKam Number 35 SEDULIUS, THE PASCHAL SONG AND HYMNS Volume Editor Michael J. Roberts SEDULIUS, THE PASCHAL SONG AND HYMNS Translated with an Introduction and Notes by Carl P. E. Springer Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta SEDULIUS, THE PASCHAL SONG AND HYMNS Copyright © 2013 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions O! ce, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sedulius, active 5th century. The Paschal song and hymns / Sedulius ; translated with an introduction >and notes by Carl P. E. Springer. p. cm. — (Society of Biblical Literature. Writings from the Greco-Roman world ; volume 35) Text in Latin and English translation on facing pages; introduction and >notes in English. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-58983-743-0 (paper binding : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-58983-744-7 (electronic format) — ISBN 978-1-58983-768-3 (hardcover binding : alk. -

Latin Epics of the New Testament: Juvencus, Sedulius, Arator

LATIN EPICS OF THE NEW TESTAMENT This page intentionally left blank Latin Epics of the New Testament Juvencus, Sedulius, Arator ROGERP.H.GREEN 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox26dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oYces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York ß Roger P. H. Green 2006 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or -

Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation

Empire of Hope and Tragedy: Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brian Swain Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Timothy Gregory, Co-advisor Anthony Kaldellis Kristina Sessa, Co-advisor Copyright by Brian Swain 2014 Abstract This dissertation explores the intersection of political and ethnic conflict during the emperor Justinian’s wars of reconquest through the figure and texts of Jordanes, the earliest barbarian voice to survive antiquity. Jordanes was ethnically Gothic - and yet he also claimed a Roman identity. Writing from Constantinople in 551, he penned two Latin histories on the Gothic and Roman pasts respectively. Crucially, Jordanes wrote while Goths and Romans clashed in the imperial war to reclaim the Italian homeland that had been under Gothic rule since 493. That a Roman Goth wrote about Goths while Rome was at war with Goths is significant and has no analogue in the ancient record. I argue that it was precisely this conflict which prompted Jordanes’ historical inquiry. Jordanes, though, has long been considered a mere copyist, and seldom treated as an historian with ideas of his own. And the few scholars who have treated Jordanes as an original author have dampened the significance of his Gothicness by arguing that barbarian ethnicities were evanescent and subsumed by the gravity of a Roman political identity. They hold that Jordanes was simply a Roman who can tell us only about Roman things, and supported the Roman emperor in his war against the Goths. -

Review Juvencus and the Death of the Messiah: a New Commentary

Histos 11 (2017) xii–xvi REVIEW JUVENCUS AND THE DEATH OF THE MESSIAH: A NEW COMMENTARY Michael Müller, Tod und Auferstehung Jesu Christi bei Iuvencus (IV 570–812). Unter- suchungen zu Dichtkunst, Theologie und Zweck der ‘Evangeliorum Libri Quattuor’. Palin- genesia 105. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2016. Pp. 413. Paperback, €68.00. ISBN 978-3-515-11340-3. onty Python’s ‘Life of Brian’ finds an ancient analogue in Juvencus’ Evangeliorum libri IV, which likewise appealed to contemporary taste, M this time by turning the Gospel-tale into soberly Virgilianesque hex- ameters. This sempervirent story culminates in the Messiah’s death and resur- rection, which as the meat-and-potatoes of the Christian message form the subject of M(üller)’s study: his book is in effect a commentary on Juvencus 4.570–812. M’s ‘Introduction’ (14) promises us a ‘philological’ commentary which is both ‘umfassend’ and ‘solide’. This commentary is divided into thir- teen pericopes. The first pericope is the denial of St. Peter. The very first scholium in this first pericope’s first section (Peter’s first denial) bodes ill for this ‘philological’ commentary by starting off with two philological foul-ups (22): while M’s quis posset fallere amantem (Aen. 4.296: instead read fallere possit) impairs Virgil’s sense and scansion, Martha talis vox (Juvenc. 4.375: instead read Marthae) reduces this Juvencan phrase to scansional and syntactic mumbo-jumbo. In the second sec- tion of this first pericope (Peter’s second denial) the apparatus to M’s text (574: limine) fails to record the variant lumine, which is however discussed in the en- suing commentary, where M’s odd in limina solis (27) is a mistake for Virgilian sub limina s. -

2. the Fate of Ovid Until the Twelfth Century

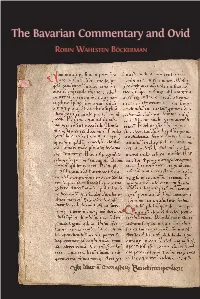

B The Bavarian Commentary and Ovid ÖCKERMAN The Bavarian Commentary and Ovid ROBIN WAHLSTEN BÖCKERMAN ROBIN WAHLSTEN BÖCKERMAN The Bavarian Commentary and Ovid is the fi rst complete cri� cal edi� on and transla� on of the earliest preserved commentary on Ovid’s Metamorphoses. T Today, Ovid’s famous work is one of the touchstones of ancient literature, but we have only a handful of scraps and quota� ons to show how the earliest medieval readers received and discussed the poems—un� l the Munich Bayerische Staatsbibliothek clm 4610. This commentary, which dates from around the year 1100 is the fi rst systema� c study of the Metamorphoses, founding a tradi� on of scholarly study that extends to the present day. Despite its signifi cance, this medieval commentary has never before been HE published or analysed as a whole. Böckerman’s groundbreaking work includes a cri� cal edi� on of the en� re manuscript, together with a lucid English transla� on B and a rigorous and s� mula� ng introduc� on, which sets the work in its historical, AVARIAN geographical and linguis� c contexts with precision and clarity while off ering a rigorous analysis of its form and func� on. C The Bavarian Commentary and Ovid is essen� al reading for academics concerned with the recep� on of Ovid or that of other ancient authors. It will also be of great OMMENTARY interest for Classical scholars, those inves� ga� ng medieval commentaries and media history, and for anyone intrigued to know more about how the work of Ovid has echoed through history. -

Evidences of Christianity. by William Paley, D.D. a New

EVIDENCES OF CHRISTIANITY. BY WILLIAM PALEY, D.D. A NEW EDITION. 1851. LONDON: PRINTED BY W.CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET. THE HONOURABLE AND RIGHT REVEREND JAMES YORK, D.D., LORD BISHOP OF ELY My LORD, When, five years ago, an important station in the University of Cambridge awaited your Lordship's disposal, you were pleased to offer it to me. The circumstances under which this offer was made demand a public acknowledgment. I had never seen your Lordship; I possessed no connection which could possibly recommend me to your favour; I was known to you only by my endeavour, in common with many others, to discharge my duty as a tutor in the University; and by some very imperfect, but certainly well-intended, and, as you thought, useful publications since. In an age by no means wanting in examples of honourable patronage, although this deserve not to be mentioned in respect of the object of your Lordship's choice, it is inferior to none in the purity and disinterestedness of the motives which suggested it. How the following work may be received, I pretend not to foretell. My first prayer concerning it is, that it may do good to any: my second hope, that it may assist, what it hath always been my earnest wish to promote, the religious part of an academical education. If in this latter view it might seem, in any degree, to excuse your Lordship's judgment of its author, I shall be gratified by the reflection that, to a kindness flowing from public principles, I have made the best public return in my power. -

The Gospel of Matthew, with the Greek and English Text Alternating

- 1 - The Gospel of Matthew part of The Holy Bible The ancient Greek text, alternating verse by verse with A new translation from the Greek by David Robert Palmer February 2020 Edition (First Edition was April 2003) freely available from: http://bibletranslation.ws/palmer-translation/ ipfs://bibletranslation.crypto ipfs://bibletranslation.zil ipfs://ebibles.crypto ipfs://ebibles.zil Printed Edition Available on Amazon http://bit.ly/PrintPostWS The textual variant data in my footnote apparatus are gathered from the United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament 3rd Edition (making adjustments for outdated data therein); the 4th Edition UBS GNT, the UBS Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, ed. Metzger; the NA27 GNT; Swanson’s Gospels apparatus; the online Münster Institute transcripts, and from Wieland Willker’s excellent online textual commentary on the Gospels. - 2 - This page intentionally blank - 3 - The Gospel of Matthew ΚΑΤΑ ΜΑΘΘΑΙΟΝ Chapter 1 The Genealogy of Jesus Mt 1:1 Βίβλος γενέσεως Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ υἱοῦ Δαυὶδ υἱοῦ Ἀβραάμ. ¹A record of the genealogy of Jesus1 the Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham: Mt 1:2 Ἀβραὰμ ἐγέννησεν τὸν Ἰσαάκ, Ἰσαὰκ δὲ ἐγέννησεν τὸν Ἰακώβ, Ἰακὼβ δὲ ἐγέννησεν τὸν Ἰούδαν καὶ τοὺς ἀδελφοὺς αὐτοῦ, ²Abraham begot Isaac, and Isaac begot Jacob, and Jacob begot Judah and his brothers, Mt 1:3 Ἰούδας δὲ ἐγέννησεν τὸν Φάρες καὶ τὸν Ζάρα ἐκ τῆς Θαμάρ, Φάρες δὲ ἐγέννησεν τὸν Ἑσρώμ, Ἑσρὼμ δὲ ἐγέννησεν τὸν Ἀράμ, ³and Judah begot Perez and Zerah, by Tamar, and Perez begot Hezron, and Hezron begot Ram, Mt 1:4 Ἀρὰμ δὲ ἐγέννησεν τὸν Ἀμιναδάβ, Ἀμιναδὰβ δὲ ἐγέννησεν τὸν Ναασσών, Ναασσὼν δὲ ἐγέννησεν τὸν Σαλμών, ⁴and Ram begot Amminadab, and Amminadab begot Nahshon, and Nahshon begot Salmon, Mt 1:5 Σαλμὼν δὲ ἐγέννησεν τὸν Βόες ἐκ τῆς Ῥαχάβ, Βόες δὲ ἐγέννησεν τὸν Ἰωβὴδ ἐκ τῆς Ῥούθ, Ἰωβὴδ δὲ ἐγέννησεν τὸν Ἰεσσαί, ⁵and Salmon begot Boaz, by Rahab, and Boaz begot Obed, by Ruth, and Obed begot Jesse, Mt 1:6 Ἰεσσαὶ δὲ ἐγέννησεν τὸν Δαυὶδ τὸν βασιλέα. -

THE LATIN NEW TESTAMENT OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, Spi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi THE LATIN NEW TESTAMENT OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 1/12/2015, SPi The Latin New Testament A Guide to its Early History, Texts, and Manuscripts H.A.G. HOUGHTON 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 14/2/2017, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © H.A.G. Houghton 2016 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2016 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and unless otherwise stated distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution –Non Commercial –No Derivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2015946703 ISBN 978–0–19–874473–3 Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Current As of November, 2013 1. Joseph Pucci

CURRICULUM VITAE http://research.brown.edu/myresearch/Joseph_Pucci Current as of November, 2013 1. Joseph Pucci Associate Professor of Classics and in the Program in Medieval Studies; Associate Professor of Comparative Literature 2. Home Address: 163 Bowen Street, Providence, RI, 02906 3. Education: 1987 Ph.D. in Comparative Literature, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1982 A.M. in Medieval History, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1979 A.B. in History (with honors), John Carroll University, Cleveland, OH 4. Appointments: a. Academic: 2007-09/ Director, Program in Medieval Studies, Brown University 1998-99 2005-06/ Chair, Department of Classics, Brown University 2000-01 2004-05 Associate Dean of the College, Brown University 1997- Associate Professor of Classics and in the Program in Medieval Studies, (with tenure) Brown University; Associate Professor of Comparative Literature as of July 1, 2002 1989-1996 Assistant Professor of Classics and in the Program in Medieval Studies, Brown University, Providence, RI (visiting appointment through 1992); William A. Dyer, Jr. Assistant Professor of the Humanities (Ancient Studies), 1996-97 1987-89 Assistant Professor of Classical Languages and Literatures and in the Honors Program (joint appointment), University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY 1986-87 Lecturer in Classical Studies, Loyola University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 1985-86 Instructor in Latin and in Greek, Lutheran School of Theology and Chicago Cluster of Theological Schools, Chicago, IL 2 December, 2013 b. Scholarly: 2013- Co-Editor, Brill's -

Printing and Reading Italian Latin Humanism in Renaissance Europe (Ca

Printing and Reading Italian Latin Humanism in Renaissance Europe (ca. 1470-ca. 1540) Printing and Reading Italian Latin Humanism in Renaissance Europe (ca. 1470-ca. 1540) By Alejandro Coroleu Printing and Reading Italian Latin Humanism in Renaissance Europe (ca. 1470-ca. 1540), by Alejandro Coroleu This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Alejandro Coroleu All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5894-3, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5894-6 CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... vi Preface ....................................................................................................... vii List of Abbreviations ................................................................................ viii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ............................................................................................... 10 Social Networks Chapter Two ............................................................................................. -

The English Inheritance of Biblical Verse

The English Inheritance of Biblical Verse By Patrick McBrine A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto © Patrick Corey McBrine 2008 Thesis Abstract Title: The English Inheritance of Biblical Verse Submitted by: Patrick McBrine Degree: Doctor of Philosophy, 2008 Department: Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Toronto “The English Inheritance of Biblical Verse” explores the transmission of late antique Latin biblical poetry to England and the subsequent development of the genre in the vernacular. This study offers close readings of the most important contributions to a genre that produced more than twenty major compositions between AD 400 and 1500. For over a millennium, this literature effectively represented the Bible in popular form, yet this is the first study to explore the stylistic and thematic affinities between the Latin and English traditions. Chapter 1 provides an introduction to ‘biblical verse,’ defines the term and offers a broad outline of the genre, including a summary of general stylistic features and critical trends. The first chapter also provides an overview of the subject matter in each of the following chapters. Chapter 2 discusses the Latin beginnings of the genre in the fourth century, beginning with the poetry of Juvencus, whose stylistic choices regarding the appropriation of classical literature establish many of the generic norms for later poets. Among them is Cyprianus, who reflects the Juvencan model in his Heptateuch, while Prudentius, though not a biblical poet per se, anticipates a movement toward stylistic freedom in later versifications of the Bible.