Download (13Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aggregates Market Investigation

LAFARGE AGGREGATES LIMITED AND LAFARGE CEMENT UK LIMITED OVERVIEW SUBMISSION IN RESPONSE TO THE COMPETITION COMMISSION’S STATEMENT OF ISSUES NON-CONFIDENTIAL VERSION April, 2012 K&E 91146101.1 OVERVIEW SUBMISSION IN RESPONSE TO THE COMPETITION COMMISSION’S STATEMENT OF ISSUES 1. This Submission is made by Lafarge Aggregates Limited and Lafarge Cement UK Limited (together, “Lafarge”) in response to the Competition Commission’s (“CC”) Statement of Issues dated 8 March 2012. A. Executive Summary 2. The timing of the CC market investigation into the supply or acquisition of aggregates, cement and ready-mix concrete (“RMX”) (the “MIR”) presents a series of challenges for both the CC and market participants, including Lafarge: Market Decline. The MIR takes place against the backdrop of an economic downturn since 2008 which has been longer and more severe than any experienced by the construction materials industry within the last 30 years. The reduction in volumes has accelerated again in 2012 with year-on-year declines for the first quarter in excess of 10 per cent for aggregates and RMX, while GB cement volumes appear likely to decline or to remain flat at best in 2012. Industry forecasts do not predict any change in these trends before at least 2014, at which point demand is expected still to remain below levels seen in 2009. Any potential improvements will develop from a low base, resulting in sustained and significant levels of overcapacity. Combination of Lafarge and Tarmac. Lafarge announced in February 2011 the proposed combination of its UK construction materials business with that of Tarmac Limited (the “Proposed JV”). -

Cement in 1994, 1.3 Million Tons Was 1.17 Million Tons Or 10% of the Total

CEMENT By Cheryl Solomon The industry's main product, portland California, Southern.—All other counties production, excluding Puerto Rico, increased by cement, makes up 95% of the total domestic in California. 5% to 74.3 million metric tons. production. The remainder comes from Chicago, Metropolitan.—The Illinois The industry operated 118 plants, including masonry, hydraulic, and aluminous cements. counties of Cook, DuPage, Kane, Kendall, 8 grinding facilities, to produce various types of In 1994, U.S. demand for cement increased Lake, McHenry, and Will. finished hydraulic cement. by approximately 7%. Domestic production of Illinois.—All other counties in Illinois. The size of individual companies, as a portland cement increased by 5%. Cement New York, Western.—All counties west of percentage of total U.S. finished cement imported for consumption increased to 11.3 a dividing line following the eastern boundaries production capacity, ranged from 0.4% to million metric tons. Portland cement values of Broome, Chenango, Lewis, Madison, 12.7%. The top 10 producing companies, in increased to approximately $61 per metric ton. Oneida, and St. Lawrence Counties. declining order of production, were Holnam New York, Eastern.—All counties east of Inc.; Lafarge Corp.; Essroc Materials, Inc., Legislation and Government Programs the aforementioned dividing line, except Southdown Inc.; Ash Grove Cement Co.; Blue At the beginning of the year, the Metropolitan New York. Circle Inc.; Lone Star Industries, Inc.; Lehigh Environmental Protection Agency announced New York, Metropolitan.—The five counties Portland Cement Co.; California Portland; and the availability of the agency's Report to of New York City (Bronx, Kings, New York, RC Cement Co., Inc. -

CRR 446/2002 a Study of the Provision of Health and Safety Information in the Annual Reports of the Top UK Companies

HSE Health & Safety Executive A study of the provision of health and safety information in the annual reports of the top UK companies Prepared by System Concepts Ltd for the Health and Safety Executive CONTRACT RESEARCH REPORT 446/2002 HSE Health & Safety Executive A study of the provision of health and safety information in the annual reports of the top UK companies Laura Peebles, Ansgar Kupper and Tanya Heasman System Concepts Ltd 2 Savoy Court Strand London WC2R 0EZ This report details the findings of a research project to investigate the quality and quantity of health and safety information found in the annual reports of the top UK companies. At present, publicly listed companies are not legally required to include health and safety matters in their annual reports. The current Health and Safety Commission (HSC) Strategy Statement, however, contains an action point which focuses on public reporting of health and safety issues by larger companies. The aim is to promote the reporting of health and safety information in company annual reports and to provide guidance that would allow reporting of such information to a common standard. To assist the HSC with this strategy, System Concepts were commissioned by the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) to undertake an investigation of the provision of health and safety information in company annual reports. The study comprised a series of steps. The main objectives of the study were: i) To determine the current level of reporting of health and safety issues in annual reports of the top UK companies ii) To determine the quality of health and safety information reported. -

Westbury Your Your

37th established 1967 Edition 20 Maps & A-Z dentons of Businessesdentons 20 your Westbury directory Westbury 2020 © Hugh Llewelyn | Flickr.com Bratton Camp INDEPENDENT FAMILY FUNERAL DIRECTOR ‘Comprehensive Domestic & Commercial Service’ • Rewires • New builds & renovations • All lighting design • Fuse board upgrade • Alarm systems • CCTV and much more 24 hour service - quietly serving Westbury & surrounding villages for more than 60 years 01373 822764 01373 253128 [email protected] [email protected] www.arthurwmays.co.uk www.allelectricalsw.co.uk Septic Tank Emptying Providing our trusted service to the • Window cleaning West Country • Gutter clear & clean • Jet wash of driveways, patios, for 40 years fencing etc. 01373 451232 Tel: 01963 370924 www.jcsjetwash.co.uk www.wessexwaste.co.uk [email protected] Domain Name Website Services Hosting Website Design & Build LinkedIn Facebook SEO Services Advertising Campaigns Thought we were just a directory? Think again... Business Card Design & Print Print Services Mailshot Big & Small Campaigns By Email or Post For a hassle free quote or more info please call Letterheads, 0844 776 1967 Leaflets, Compliment Slips etc. etc. FOR MORE DETAILS ON OUR PRIVACY POLICY PLEASE VISIT OUR WEBSITE Contact us: Dentons Directories Ltd., Bridge House, Stati on Road, Westbury, BA13 4HR • www.dentonsdirectories.com 2 • search online at dentons.net A A ACCESS EQUIPMENT ADVERTISING & SEE PLANT & MACHINERY; SCAFFOLDING PROMOTIONAL PRODUCTS A B SEE SIGNS ACCOMMODATION A C SEE BED & BREAKFAST; CAMPING -

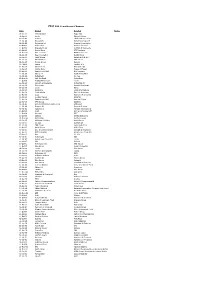

Appendix a Companies Excluded from the Sample

Appendix A Companies Excluded from the Sample The 504 companies excluded from the sample are identified below. Along with the company name the original Times 1000 rank number (1970) is given. Reasons for exclusion are: - Company is not British. - Company is not the parent company. - Company has been taken over or has been subject to merger during the study period. - Company is not public quoted. - Company is a bank, finance house or similar. - Company has gone into liquidation during the study period. - Company is government-owned or -controlled. - 50 per cent or more of company shares are within a single holding, i.e. effectively giving outside. control. - Company has completely reformed its capital structure (e.g. by unbundling), thus voiding data continuity. Times 1000 Times 1000 Rank no. Company name Rank no. Company name (1970) (1970) 445 Aberdare Holdings 609 Army & Navy Stores 540 A D International 444 Aspro-Nicholas 477 Adams Butter 013 Associated British Foods 905 Advance Electronics 495 Associated British Maltsters 762 Aerialite 715 Atkinson Lorries 464 Aire Wool 868 Atlas Stone 093 Albright & Wilson 836 Austin-Hall Group 162 Alcan Aluminium 953 Australian Agriculture 349 Alcoa of Great Britain 151 Australian Estates Co. 682 Edgar Allen 330 Averys 661 Alliance Alders 599 A VP Industries 664 Allied English Potteries 630 A W Securities 045 Allied Suppliers 241 Bakelite Xylonite 040 Amalgamated Metal Corpora 613 Balfour Darwins tion 611 Bambergers 880 Jeremiah Ambler 837 Banbury Buildings Holdings 392 Arney Group 718 Bardolin 442 Anglo Thai Corporation 941 Barr & Stroud 388 Armour & Co. 897 Barrow Barnsley 177 178 The Strategy and Performance of British Industry, 1970-80 Times 1000 Times 1000 Rank no. -

Strassmann, Inc. Global Information Productivity® Rankings © Copyright 1997, All Rights Reserved

Strassmann, Inc. Global Information Productivity® Rankings © Copyright 1997, All Rights Reserved This document contains selected 1995 Information Productivity® rankings from industrial companies in Strassmann, Inc.’s database of 8,600 global firms. The 1996 ranking of industrial firms will appear in The Productivity of Information Management , The Information Economics Press, 1998. Definitions Rank: Information Productivity (IP) rankings of 510 industrial firms, with employment of over 15,000 and satisfying a number of financial criteria. Information Management Expenses: Sales, General, Administrative, Research and Development costs. Profits: Net Income after Income Taxes, before Preferred Dividends About Strassmann, Inc. Strassmann, Inc. offers Information Productivity Assessment services to firms wishing to benchmark their performance. Comparisons are made against look-alike firms as well as competitors. Ten year trend analysis in factors contributing to Information Productivity are included in each case. For further information and analytical services, send email to [email protected], or visit our web site, http://www.strassmann.com Available Services 1. Information Productivity ® Assessment Ranking a firm’s information management performance as compared with look- alike organizations. Includes: Ten year analysis of trends, ratio of information to finance costs, correlation with standard measures of financial performance and tabulation of over- or under-performance relative to industry peer group. Detects shifts from labor to capital-intensive information work. Application: Diagnostic method for justifying, planning and budgeting expenditures for information resources. 2. Knowledge Capital ® Assessment Ranking a firm’s performance in terms of is accumulation of knowledge assets as compared with-alike organizations. Includes: Ten year trend analyses, ratio of finance and knowledge capital, comparisons with market valuation (if available) and valuation of employees as assets and not as an expense. -

Case No COMP/M.1874 - LAFARGE / BLUE CIRCLE

EN Case No COMP/M.1874 - LAFARGE / BLUE CIRCLE Only the English text is available and authentic. REGULATION (EEC) No 4064/89 MERGER PROCEDURE Article 6(2) NON-OPPOSITION Date: 07/04/2000 Also available in the CELEX database Document No 300M1874 Office for Official Publications of the European Communities L-2985 Luxembourg COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 07.04.2000 SG(2000) D/102992 In the published version of this decision, some PUBLIC VERSION information has been omitted pursuant to Article 17(2) of Council Regulation (EEC) No 4064/89 concerning non-disclosure of business secrets and MERGER PROCEDURE other confidential information. The omissions are ARTICLE 6(2) DECISION shown thus […]. Where possible the information omitted has been replaced by ranges of figures or a general description. To the notifying party Dear Sirs, Subject : Case No COMP/M.1874 – LAFARGE / BLUE CIRCLE Notification of 29.02.2000 pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulation No. 4064/89 1. On 29/02/2000, the Commission received a notification of a proposed concentration pursuant to Article 4 of Council Regulatioin (EEC) No 4064/89 by which the undertaking Lafarge S.A. (‘Lafarge’) acquires within the meaning of Article 3(1)b of the Council Regulation control of the whole of Blue Circle Industries plc. (“BCI”), by way of a public bid. 2. After examination of the notification, the Commission has concluded that the notified operations falls within the scope of the Council Regulation No 4064/89 and does not raise serious doubts as to its compatibility with the common market and the functioning of the EEA Agreement. -

Lafarge Publication

Annual Report2005 On Form 20-F Lafarge Annual Report On Form 20-F 2005 PRESENTATION OF INFORMATION “Growing markets”: all countries outside Western Europe and North America, except Japan, Australia and In this Annual Report, the following terms have the mea- New Zealand. nings indicated below: “Group” or “Lafarge”: Lafarge S.A. and its consolidated “Euro” or “€”: the currency of the European Union subsidiaries. member states participating in the European Monetary Union. “Company” or “Lafarge S.A.”: our parent company Lafarge S.A., a société anonyme organized under French “U.S. dollars” or “$”: the currency of the United States, 20unless otherwise indicated. law. “Division”: one of our four Divisions: Cement, Aggregates “IFRS”: International Financial Reporting Standards & Concrete, Roofing and Gypsum. Each Division, as well “Tonne”: 1,000 kilograms, or 2,204 pounds, or 1,102 as our “Other activities”, constitutes a business segment short tons. for purposes of reporting our results of operations. Due to rounding of amounts and percentages for presen- “Business Unit”: a management organization for one tation in this annual report, some data may not total. of our four Divisions in one geographic area, generally one country. We publish our consolidated financial statements in euro. Solely for the convenience of the reader, this annual “ERP”: enterprise resource planning. report contains translations into U.S. dollars of certain “France”: the Republic of France. amounts in euros at the December 30, 2005 Noon Buying Rate of 1 euro = $1.1842. “E.U.”: the European Union. “United States”, the “U.S.” or the “U.S.A.”: the United States of America. -

Low Carbon Evidence Base for the West Midlands Regional Economic Strategy

Low Carbon Evidence Base for the West Midlands Regional Economic Strategy Prepared for Advantage West Midlands October 2007 Final Report Project N° 44408193 Low Carbon Evidence Base for the West Midlands Regional Economic Strategy Report Title: Low Carbon Evidence Base for the West Midlands Regional Economic Strategy Project No: 44408193 Status: Final report Client Company Name: Advantage West Midlands (AWM) Issued by: URS Corporation Ltd St Georges’ House 5 St Georges’ Road Wimbledon SW19 4DR United Kingdom Document Production / Approval Record Name Signature Date Position October Prepared by Lise Van Long Project Manager 2007 October Director Sustainable Checked by Sally Vivian 2007 Solutions UK & Ireland October Director Sustainable Approved by Sally Vivian 2007 Solutions UK & Ireland October 2007 Final Report Low Carbon Evidence Base for the West Midlands Regional Economic Strategy LIMITATION URS Corporation Limited (URS) has prepared this Report for the sole use of Advantage West Midlands in accordance with the Agreement under which our services were performed. No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the professional advice included in this Report or any other services provided by us. This Report may not be relied upon by any other party without the prior and express written agreement of URS. The conclusions and recommendations contained in this Report are based upon information provided by others and upon the assumption that all relevant information has been provided by those parties from whom it has been requested. Information obtained from third parties has not been independently verified by URS, unless otherwise stated in the Report. COPYRIGHT © This Report is the copyright of URS Corporation Limited. -

FTSE 100 Constituent History Updated

FTSE 100 Constituent Changes Date Added Deleted Notes 19-Jan-84 CJ Rothschild Eagle Star 02-Apr-84 Lonrho Magnet Sthrns. 02-Jul-84 Reuters Edinburgh Inv. Trust 02-Jul-84 Woolworths Barrat Development 19-Jul-84 Enterprise Oil Bowater Corporation 01-Oct-84 Willis Faber Wimpey (George) 01-Oct-84 Granada Group Scottish & Newcastle 01-Oct-84 Dowty Group MFI Furniture 04-Dec-84 Brit. Telecom Matthey Johnson 02-Jan-85 Dee Corporation Dowty Group 02-Jan-85 Argyll Group Berisford (S.& W.) 02-Jan-85 MFI Furniture RMC Group 02-Jan-85 Dixons Group Dalgety 01-Feb-85 Jaguar Hambro Life 01-Apr-85 Guinness (A) Enterprise Oil 01-Apr-85 Smiths Inds. House of Fraser 01-Apr-85 Ranks Hovis McD. MFI Furniture 01-Jul-85 Abbey Life Ranks Hovis McD. 01-Jul-85 Debenhams I.C. Gas 06-Aug-85 Bnk. Scotland Debenhams 01-Oct-85 Habitat Mothercare Lonrho 02-Jan-86 Scottish & Newcastle Rothschild (J) 08-Jan-86 Storehouse Habitat Mothercare 08-Jan-86 Lonrho B.H.S. 01-Apr-86 Wellcome EXCO International 01-Apr-86 Coats Viyella Sun Life Assurance 01-Apr-86 Lucas Harrisons & Crosfield 01-Apr-86 Cookson Group Ultramar 21-Apr-86 Ranks Hovis McD. Imperial Group 22-Apr-86 RMC Group Distillers 01-Jul-86 British Printing & Comms. Corp Abbey Life 01-Jul-86 Burmah Oil Bank of Scotland 01-Jul-86 Saatchi & S. Ferranti International 01-Oct-86 Bunzl Brit. & Commonwealth 01-Oct-86 Amstrad BICC 01-Oct-86 Unigate Smiths Industries 09-Dec-86 British Gas Northern Foods 02-Jan-87 Hillsdown Holdings Argyll Group 02-Jan-87 I.C. -

Technical and Economic Review of Cement and Lime Process

Environment Agency Information Centre TECHNICAL AND ECONOMIC REVIEW OF CEMENT AND LIME PROCESS Research undertaken for the Environment Agency Contract Ref: HMIP/CPR2/41/197 Title: Technical & Economic Study of Processes Within the Minerals Processing Sector National Information Centre The Environment Agency Rio House Waterside Drive Aztec West BRISTOL BS12 4UD Due for return The results of this work will be used in the formulation of Environment Agency policy but Views expressed in this report do not necessarily represent Environment Agency policy. TECHNICAL AND ECONOMIC REVIEW OF CEMENT AND LIME PROCESSES A Report to the Environment Agency August 1996 TECHNICAL AND ECONOMIC REVIEW OF CEMENT AND UME PROCESSES CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i 1. BAT ASSESSMENT FOR CEMENT AND LIME INDUSTRIES 1 1.1 Background............................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Report Scop© ........................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Report Objectives..................................................................................................... 1 1.4 Report Structure ....................................................................................................... 2 2. CEMENT PROCESSES .................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 The Sector.................................................................................................. ............. -

FTSE 100 Original Constituents.Xls

FT-SE 100 Share Index original constituents Index Commenced 03rd January 1984. Base date 31/12/1983 with index value of 1000 Allied - Lyons Imperial Chemical Industries Associated Bitish Foods Imperial Cont. Gas Association Associated Dairies Group Imperial Group Barclays Bank Johnson Matthey Barratt Developments Ladbroke Group Bass Land Securities BAT Industries Legal & General Group Beecham Group Lloyds Bank Berisford (S. & W.) Magnet & Southerns BICC MEPC Blue Circle Industries MFI Furniture Group BOC Group Marks & Spencer Boots Co. Midland Bank Bowater Corporation National Westminster Bank BPB Industries Northern Foods British & Commonwealth P & O Steam Navigation Co. British Aerospace Pearson (S.) & Son British Elect. Traction Co. Pilkington Brothers British Home Stores Plessey Co. British Petroleum Prudential Corporation Britoil RMC Group BTR Racal Electronics Burton Group Rank Organisation Cable & Wireless Reckitt & Colman Cadbury Schweppes Redland Commercial Union Assurance Reed International Consolidated Gold Fields Rio Tinto - Zinc Corporation Courtaulds Rowntree Mackintosh Dalgety Royal Bank of Scotland Group Distillers Co. Royal Insurance Eagle Star Sainsbury (J.) Edinburgh Investment Trust Scottish & Newcastle Breweries English China Clays Sears Holdings Exco International Sedgwick Group Ferranti Shell Trans. & Trad. Co. Fisons Smith & Nephew Associated Co's. General Accident Fire & Life Standard Chartered Bank General Electric Standard Telephones & Cables Glaxo Holdings Sun Alliance & London Insurance Globe Investment Trust Sun Life Assurance Society Grand Metropolitan THORN EMI Great Universal Stores 'A' Tarmac Guardian Royal Exchange Tesco Guest Keen & Nettlefolds Trafalgar House Hambro Life Assurance Trusthouse Forte Hammerson Prop.Inv. & Dev. 'A' Ultramar Hanson Trust Unilever Harrisons & Crossfield United Biscuits Hawker Siddeley Group Whitbread & Co. 'A' House of Fraser Wimpey (George) Page 1 of 1, FTSE 100 original constituents.xls.