Genetic Assessment of the Mating System and Patterns of Egg Cannibalism in Atka Mackerel M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Sea of Okhotsk, Sakhalin Island): 2. Cyclopteridae−Molidae Families

ISSN 0032-9452, Journal of Ichthyology, 2018, Vol. 58, No. 5, pp. 633–661. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2018. An Annotated List of the Marine and Brackish-Water Ichthyofauna of Aniva Bay (Sea of Okhotsk, Sakhalin Island): 2. Cyclopteridae−Molidae Families Yu. V. Dyldina, *, A. M. Orlova, b, c, d, A. Ya. Velikanove, S. S. Makeevf, V. I. Romanova, and L. Hanel’g aTomsk State University (TSU), Tomsk, Russia bRussian Federal Research Institute of Fishery and Oceanography (VNIRO), Moscow, Russia cInstitute of Ecology and Evolution, Russian Academy of Sciences (IPEE), Moscow, Russia d Dagestan State University (DSU), Makhachkala, Russia eSakhalin Research Institute of Fisheries and Oceanography (SakhNIRO), Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, Russia fSakhalin Basin Administration for Fisheries and Conservation of Aquatic Biological Resources—Sakhalinrybvod, Aniva, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, Russia gCharles University in Prague, Prague, Czech Republic *e-mail: [email protected] Received March 1, 2018 Abstract—The second, final part of the work contains a continuation of the annotated list of fish species found in the marine and brackish waters of Aniva Bay (southern part of the Sea of Okhotsk, southern part of Sakhalin Island): 137 species belonging to three orders (Perciformes, Pleuronectiformes, Tetraodon- tiformes), 31 family, and 124 genera. The general characteristics of ichthyofauna and a review of the commer- cial fishery of the bay fish, as well as the final systematic essay, are presented. Keywords: ichthyofauna, annotated list, conservation status, commercial importance, marine and brackish waters, Aniva Bay, southern part of the Sea of Okhotsk, Sakhalin Island DOI: 10.1134/S0032945218050053 INTRODUCTION ANNOTATED LIST OF FISHES OF ANIVA BAY The second part concludes the publication on the 19. -

Does Climate Change Bolster the Case for Fishery Reform in Asia? Christopher Costello∗

Does Climate Change Bolster the Case for Fishery Reform in Asia? Christopher Costello∗ I examine the estimated economic, ecological, and food security effects of future fishery management reform in Asia. Without climate change, most Asian fisheries stand to gain substantially from reforms. Optimizing fishery management could increase catch by 24% and profit by 34% over business- as-usual management. These benefits arise from fishing some stocks more conservatively and others more aggressively. Although climate change is expected to reduce carrying capacity in 55% of Asian fisheries, I find that under climate change large benefits from fishery management reform are maintained, though these benefits are heterogeneous. The case for reform remains strong for both catch and profit, though these numbers are slightly lower than in the no-climate change case. These results suggest that, to maximize economic output and food security, Asian fisheries will benefit substantially from the transition to catch shares or other economically rational fishery management institutions, despite the looming effects of climate change. Keywords: Asia, climate change, fisheries, rights-based management JEL codes: Q22, Q28 I. Introduction Global fisheries have diverged sharply over recent decades. High governance, wealthy economies have largely adopted output controls or various forms of catch shares, which has helped fisheries in these economies overcome inefficiencies arising from overfishing (Worm et al. 2009) and capital stuffing (Homans and Wilen 1997), and allowed them to turn the corner toward sustainability (Costello, Gaines, and Lynham 2008) and profitability (Costello et al. 2016). But the world’s largest fishing region, Asia, has instead largely pursued open access and input controls, achieving less long-run fishery management success (World Bank 2017). -

Wholesale Market Profiles for Alaska Groundfish and Crab Fisheries

JANUARY 2020 Wholesale Market Profiles for Alaska Groundfish and FisheriesCrab Wholesale Market Profiles for Alaska Groundfish and Crab Fisheries JANUARY 2020 JANUARY Prepared by: McDowell Group Authors and Contributions: From NOAA-NMFS’ Alaska Fisheries Science Center: Ben Fissel (PI, project oversight, project design, and editor), Brian Garber-Yonts (editor). From McDowell Group, Inc.: Jim Calvin (project oversight and editor), Dan Lesh (lead author/ analyst), Garrett Evridge (author/analyst) , Joe Jacobson (author/analyst), Paul Strickler (author/analyst). From Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission: Bob Ryznar (project oversight and sub-contractor management), Jean Lee (data compilation and analysis) This report was produced and funded by the NOAA-NMFS’ Alaska Fisheries Science Center. Funding was awarded through a competitive contract to the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission and McDowell Group, Inc. The analysis was conducted during the winter of 2018 and spring of 2019, based primarily on 2017 harvest and market data. A final review by staff from NOAA-NMFS’ Alaska Fisheries Science Center was completed in June 2019 and the document was finalized in March 2016. Data throughout the report was compiled in November 2018. Revisions to source data after this time may not be reflect in this report. Typically, revisions to economic fisheries data are not substantial and data presented here accurately reflects the trends in the analyzed markets. For data sourced from NMFS and AKFIN the reader should refer to the Economic Status Report of the Groundfish Fisheries Off Alaska, 2017 (https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/resource/data/2017-economic-status-groundfish-fisheries-alaska) and Economic Status Report of the BSAI King and Tanner Crab Fisheries Off Alaska, 2018 (https://www.fisheries.noaa. -

Biodiversity of Arctic Marine Fishes: Taxonomy and Zoogeography

Mar Biodiv DOI 10.1007/s12526-010-0070-z ARCTIC OCEAN DIVERSITY SYNTHESIS Biodiversity of arctic marine fishes: taxonomy and zoogeography Catherine W. Mecklenburg & Peter Rask Møller & Dirk Steinke Received: 3 June 2010 /Revised: 23 September 2010 /Accepted: 1 November 2010 # Senckenberg, Gesellschaft für Naturforschung and Springer 2010 Abstract Taxonomic and distributional information on each Six families in Cottoidei with 72 species and five in fish species found in arctic marine waters is reviewed, and a Zoarcoidei with 55 species account for more than half list of families and species with commentary on distributional (52.5%) the species. This study produced CO1 sequences for records is presented. The list incorporates results from 106 of the 242 species. Sequence variability in the barcode examination of museum collections of arctic marine fishes region permits discrimination of all species. The average dating back to the 1830s. It also incorporates results from sequence variation within species was 0.3% (range 0–3.5%), DNA barcoding, used to complement morphological charac- while the average genetic distance between congeners was ters in evaluating problematic taxa and to assist in identifica- 4.7% (range 3.7–13.3%). The CO1 sequences support tion of specimens collected in recent expeditions. Barcoding taxonomic separation of some species, such as Osmerus results are depicted in a neighbor-joining tree of 880 CO1 dentex and O. mordax and Liparis bathyarcticus and L. (cytochrome c oxidase 1 gene) sequences distributed among gibbus; and synonymy of others, like Myoxocephalus 165 species from the arctic region and adjacent waters, and verrucosus in M. scorpius and Gymnelus knipowitschi in discussed in the family reviews. -

Japan Update to 05.04.2021 Approval No Name Address Products Number FROZEN CHUM SALMON DRESSED (Oncorhynchus Keta)

Japan Update to 05.04.2021 Approval No Name Address Products Number FROZEN CHUM SALMON DRESSED (Oncorhynchus keta). FROZEN DOLPHINFISH DRESSED (Coryphaena hippurus). FROZEN JAPANESE SARDINE ROUND (Sardinops 81,Misaki-Cho,Rausu- Kaneshin Tsuyama melanostictus). FROZEN ALASKA POLLACK DRESSED (Theragra chalcogramma). 1 VN01870001 Cho, Menashi- Co.,Ltd FROZEN ALASKA POLLACK ROUND (Theragra chalcogramma). FROZEN PACIFIC COD Gun,Hokkaido,Japan DRESSED. (Gadus macrocephalus). FROZEN PACIFIC COD ROUND. (Gadus macrocephalus) Maekawa Shouten Hokkaido Nemuro City Fresh Fish (Excluding Fish By-Product); Fresh Bivalve Mollusk.; Frozen Fish (Excluding 2 VN01860002 Co., Ltd Nishihamacho 10-177 Fish By-Product); Frozen Processed Bivalve Mollusk; Frozen Chum Salmon(Round,Dressed,Semi-Dressed,Fillet,Head,Bone,Skin); Frozen 1-35-1 Alaska Pollack(Round,Dressed,Semi-Dressed,Fillet); Frozen Pacific Taiyo Sangyo Co.,Ltd. 3 VN01840003 Showachuo,Kushiro- Cod(Round,Dressed,Semi-Dressed,Fillet); Frozen Pacific Saury(Round,Dressed,Semi- Kushiro Factory City,Hokkaido,Japan Dressed); Frozen Chub Mackerel(Round,Fillet); Frozen Blue Mackerel(Round,Fillet); Frozen Salted Pollack Roe 3-9 Komaba- Taiyo Sangyo Co.,Ltd. 4 VN01860004 Cho,Nemuro- Frozen Fish ; Frozen Processed Fish; (Excluding By-Product) Nemuro Factory City,Hokkaido,Japan 3-2-20 Kitahama- Marutoku Abe Suisan 5 VN01920005 Cho,Monbetu- Frozen Chum Salmon Dressed; Frozen Salmon Dressed Co.,Ltd City,Hokkaido,Japan Frozen Chum Salmon(Round,Semi-Dressed,Fillet); Frozen Salmon Milt; Frozen Pink Salmon(Round,Semi-Dressed,Dressed,Fillet); -

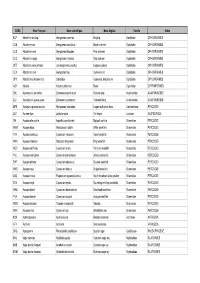

Approved List of Japanese Fishery Fbos for Export to Vietnam Updated: 11/6/2021

Approved list of Japanese fishery FBOs for export to Vietnam Updated: 11/6/2021 Business Approval No Address Type of products Name number FROZEN CHUM SALMON DRESSED (Oncorhynchus keta) FROZEN DOLPHINFISH DRESSED (Coryphaena hippurus) FROZEN JAPANESE SARDINE ROUND (Sardinops melanostictus) FROZEN ALASKA POLLACK DRESSED (Theragra chalcogramma) 420, Misaki-cho, FROZEN ALASKA POLLACK ROUND Kaneshin Rausu-cho, (Theragra chalcogramma) 1. Tsuyama CO., VN01870001 Menashi-gun, FROZEN PACIFIC COD DRESSED LTD Hokkaido, Japan (Gadus macrocephalus) FROZEN PACIFIC COD ROUND (Gadus macrocephalus) FROZEN DOLPHIN FISH ROUND (Coryphaena hippurus) FROZEN ARABESQUE GREENLING ROUND (Pleurogrammus azonus) FROZEN PINK SALMON DRESSED (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) - Fresh fish (excluding fish by-product) Maekawa Hokkaido Nemuro - Fresh bivalve mollusk. 2. Shouten Co., VN01860002 City Nishihamacho - Frozen fish (excluding fish by-product) Ltd 10-177 - Frozen processed bivalve mollusk Frozen Chum Salmon (round, dressed, semi- dressed,fillet,head,bone,skin) Frozen Alaska Pollack(round,dressed,semi- TAIYO 1-35-1 dressed,fillet) SANGYO CO., SHOWACHUO, Frozen Pacific Cod(round,dressed,semi- 3. LTD. VN01840003 KUSHIRO-CITY, dressed,fillet) KUSHIRO HOKKAIDO, Frozen Pacific Saury(round,dressed,semi- FACTORY JAPAN dressed) Frozen Chub Mackerel(round,fillet) Frozen Blue Mackerel(round,fillet) Frozen Salted Pollack Roe TAIYO 3-9 KOMABA- SANGYO CO., CHO, NEMURO- - Frozen fish 4. LTD. VN01860004 CITY, - Frozen processed fish NEMURO HOKKAIDO, (excluding by-product) FACTORY JAPAN -

Highly Discordant Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Diversities in Atka Mackerel M

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Publications, Agencies and Staff of the .SU . U.S. Department of Commerce Department of Commerce 2010 Highly Discordant Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Diversities in Atka Mackerel M. F. Canino National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Seattle, Washington, [email protected] I. B. Spies National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Seattle, Washington S. A. Lowe National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, Seattle, Washington W. S. Grant University of Alaska Anchorage Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub Canino, M. F.; Spies, I. B.; Lowe, S. A.; and Grant, W. S., "Highly Discordant Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Diversities in Atka Mackerel" (2010). Publications, Agencies and Staff of ht e U.S. Department of Commerce. 532. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub/532 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Commerce at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications, Agencies and Staff of the .SU . Department of Commerce by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Marine and Coastal Fisheries: Dynamics, Management, and Ecosystem Science 2:375–387, 2010 [Special Section: Atka Mackerel] Ó Copyright by the American Fisheries Society 2010 DOI: 10.1577/C09-024.1 Highly Discordant Nuclear and Mitochondrial DNA Diversities in Atka Mackerel M. F. CANINO,* I. B. SPIES, AND S. A. LOWE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Fisheries, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, 7600 Sand Point Way Northeast, Seattle, Washington 98115, USA W. -

1 CWU Comparative Osteology Collection, List of Specimens

CWU Comparative Osteology Collection, List of Specimens List updated November 2019 0-CWU-Collection-List.docx Specimens collected primarily from North American mid-continent and coastal Alaska for zooarchaeological research and teaching purposes. Curated at the Zooarchaeology Laboratory, Department of Anthropology, Central Washington University, under the direction of Dr. Pat Lubinski, [email protected]. Facility is located in Dean Hall Room 222 at CWU’s campus in Ellensburg, Washington. Numbers on right margin provide a count of complete or near-complete specimens in the collection. Specimens on loan from other institutions are not listed. There may also be a listing of mount (commercially mounted articulated skeletons), part (partial skeletons), skull (skulls), or * (in freezer but not yet processed). Vertebrate specimens in taxonomic order, then invertebrates. Taxonomy follows the Integrated Taxonomic Information System online (www.itis.gov) as of June 2016 unless otherwise noted. VERTEBRATES: Phylum Chordata, Class Petromyzontida (lampreys) Order Petromyzontiformes Family Petromyzontidae: Pacific lamprey ............................................................. Entosphenus tridentatus.................................... 1 Phylum Chordata, Class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fishes) unidentified shark teeth ........................................................ ........................................................................... 3 Order Squaliformes Family Squalidae Spiny dogfish ........................................................ -

ASFIS ISSCAAP Fish List February 2007 Sorted on Scientific Name

ASFIS ISSCAAP Fish List Sorted on Scientific Name February 2007 Scientific name English Name French name Spanish Name Code Abalistes stellaris (Bloch & Schneider 1801) Starry triggerfish AJS Abbottina rivularis (Basilewsky 1855) Chinese false gudgeon ABB Ablabys binotatus (Peters 1855) Redskinfish ABW Ablennes hians (Valenciennes 1846) Flat needlefish Orphie plate Agujón sable BAF Aborichthys elongatus Hora 1921 ABE Abralia andamanika Goodrich 1898 BLK Abralia veranyi (Rüppell 1844) Verany's enope squid Encornet de Verany Enoploluria de Verany BLJ Abraliopsis pfefferi (Verany 1837) Pfeffer's enope squid Encornet de Pfeffer Enoploluria de Pfeffer BJF Abramis brama (Linnaeus 1758) Freshwater bream Brème d'eau douce Brema común FBM Abramis spp Freshwater breams nei Brèmes d'eau douce nca Bremas nep FBR Abramites eques (Steindachner 1878) ABQ Abudefduf luridus (Cuvier 1830) Canary damsel AUU Abudefduf saxatilis (Linnaeus 1758) Sergeant-major ABU Abyssobrotula galatheae Nielsen 1977 OAG Abyssocottus elochini Taliev 1955 AEZ Abythites lepidogenys (Smith & Radcliffe 1913) AHD Acanella spp Branched bamboo coral KQL Acanthacaris caeca (A. Milne Edwards 1881) Atlantic deep-sea lobster Langoustine arganelle Cigala de fondo NTK Acanthacaris tenuimana Bate 1888 Prickly deep-sea lobster Langoustine spinuleuse Cigala raspa NHI Acanthalburnus microlepis (De Filippi 1861) Blackbrow bleak AHL Acanthaphritis barbata (Okamura & Kishida 1963) NHT Acantharchus pomotis (Baird 1855) Mud sunfish AKP Acanthaxius caespitosa (Squires 1979) Deepwater mud lobster Langouste -

Worse Things Happen at Sea: the Welfare of Wild-Caught Fish

[ “One of the sayings of the Holy Prophet Muhammad(s) tells us: ‘If you must kill, kill without torture’” (Animals in Islam, 2010) Worse things happen at sea: the welfare of wild-caught fish Alison Mood fishcount.org.uk 2010 Acknowledgments Many thanks to Phil Brooke and Heather Pickett for reviewing this document. Phil also helped to devise the strategy presented in this report and wrote the final chapter. Cover photo credit: OAR/National Undersea Research Program (NURP). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Dept of Commerce. 1 Contents Executive summary 4 Section 1: Introduction to fish welfare in commercial fishing 10 10 1 Introduction 2 Scope of this report 12 3 Fish are sentient beings 14 4 Summary of key welfare issues in commercial fishing 24 Section 2: Major fishing methods and their impact on animal welfare 25 25 5 Introduction to animal welfare aspects of fish capture 6 Trawling 26 7 Purse seining 32 8 Gill nets, tangle nets and trammel nets 40 9 Rod & line and hand line fishing 44 10 Trolling 47 11 Pole & line fishing 49 12 Long line fishing 52 13 Trapping 55 14 Harpooning 57 15 Use of live bait fish in fish capture 58 16 Summary of improving welfare during capture & landing 60 Section 3: Welfare of fish after capture 66 66 17 Processing of fish alive on landing 18 Introducing humane slaughter for wild-catch fish 68 Section 4: Reducing welfare impact by reducing numbers 70 70 19 How many fish are caught each year? 20 Reducing suffering by reducing numbers caught 73 Section 5: Towards more humane fishing 81 81 21 Better welfare improves fish quality 22 Key roles for improving welfare of wild-caught fish 84 23 Strategies for improving welfare of wild-caught fish 105 Glossary 108 Worse things happen at sea: the welfare of wild-caught fish 2 References 114 Appendix A 125 fishcount.org.uk 3 Executive summary Executive Summary 1 Introduction Perhaps the most inhumane practice of all is the use of small bait fish that are impaled alive on There is increasing scientific acceptance that fish hooks, as bait for fish such as tuna. -

Nom Français

CODE Nom Français Nom scientifique Nom Anglais Famille Ordre KCP Abadèche du Cap Genypterus capensis Kingklip Ophidiidae OPHIDIIFORMES CUB Abadèche noir Genypterus maculatus Black cusk-eel Ophidiidae OPHIDIIFORMES CUS Abadèche rosé Genypterus blacodes Pink cusk-eel Ophidiidae OPHIDIIFORMES CUC Abadèche rouge Genypterus chilensis Red cusk-eel Ophidiidae OPHIDIIFORMES OFZ Abadèche sans jambes Lamprogrammus exutus Legless cuskeel Ophidiidae OPHIDIIFORMES CEX Abadèches nca Genypterus spp Cusk-eels nei Ophidiidae OPHIDIIFORMES OPH Abadèches, brotules nca Ophidiidae Cusk-eels, brotulas nei Ophidiidae OPHIDIIFORMES ALR Ablette Alburnus alburnus Bleak Cyprinidae CYPRINIFORMES ZML Acanthure à pierreries Zebrasoma gemmatum Spotted tang Acanthuridae ACANTHUROIDEI ZLV Acanthure à queue jaune Zebrasoma xanthurum Yellowtail tang Acanthuridae ACANTHUROIDEI MPS Achigan à grande bouche Micropterus salmoides Largemouth black bass Centrarchidae PERCOIDEI LQT Acmée râpe Lottia limatula File limpet Lottiidae GASTROPODA ISA Acoupa aile-courte Isopisthus parvipinnis Bigtooth corvina Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI WEW Acoupa blanc Atractoscion nobilis White weakfish Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI YNV Acoupa cambucu Cynoscion virescens Green weakfish Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI WKK Acoupa chasseur Macrodon ancylodon King weakfish Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI WEP Acoupa du Pérou Cynoscion analis Peruvian weakfish Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI YNJ Acoupa mongolare Cynoscion jamaicensis Jamaica weakfish Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI SWF Acoupa pintade Cynoscion nebulosus Spotted weakfish Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI WKS Acoupa -

Stock Assessment of BSAI Atka Mackerel

17. Assessment of the Atka mackerel stock in the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands Sandra Lowe, James Ianelli, and Wayne Palsson Executive Summary Relative to the November 2017 SAFE report, the following substantive changes have been made in the assessment of Atka mackerel. Summary of Changes in Assessment Input 1. The 2017 catch estimate was updated, and estimated total catch for 2018 was set equal to the TAC (71,000 t). 2. Estimated 2019 and 2020 catches are 58,900 t and 54,500 t, respectively. 3. The 2017 fishery age composition data were added. 4. The 2018 Aleutian Islands survey biomass estimates were added. 5. The estimated average selectivity for 2013-2017 was used for projections. 6. We assume that approximately 86% of the BSAI-wide ABC is likely to be taken under the revised Steller Sea Lion Reasonable and Prudent Alternatives (SSL RPAs) implemented in 2015. This percentage was applied to the 2019 and 2020 maximum permissible ABCs, and those reduced amounts were assumed to be caught in order to estimate the 2019 and 2020 ABCs and OFL values. 7. As in 2017, the sample sizes specified for fishery age composition data were rescaled to have the same means as in the original baseline model (100), but varied relative to the number of hauls for the fishery. The 2017 data were added. 8. The 1986 survey age data were removed. Summary of Changes in the Assessment Methodology There were no changes in the model configuration. Summary of Results 1. The addition of the 2017 fishery age composition information impacted the estimated magnitude of the 2011 year class which decreased 12%, relative to last year’s assessment, and the magnitude of the 2013 year class which increased 12% relative to last year assessment.