Old Bones: a Recent History of Urban Placemaking in Kitchener, Ontario

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forward Looking Statements

TORSTAR CORPORATION 2020 ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM March 20, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS FORWARD LOOKING STATEMENTS ....................................................................................................................................... 1 I. CORPORATE STRUCTURE .......................................................................................................................................... 4 A. Name, Address and Incorporation .......................................................................................................................... 4 B. Subsidiaries ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 II. GENERAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE BUSINESS ....................................................................................................... 4 A. Three-Year History ................................................................................................................................................ 5 B. Recent Developments ............................................................................................................................................. 6 III. DESCRIPTION OF THE BUSINESS .............................................................................................................................. 6 A. General Summary................................................................................................................................................... 6 B. -

Next Stop:?Northfield?Station | Your Online Newspaper for Waterloo

Next stop: Northfield Station | Your online newspaper for Waterloo, Ontario http://www.waterloochronicle.ca/news/next-stop northfield station/ Movies Print Editions Submit an Event Overcast 2° C | Weather Forecast Login | Register Search this Site Search Waterloo area businesses Full Text Archive Home News Sports What’s On Opinion Community Announcements Cars Classifieds Jobs Real Estate Rentals Shopping HOT TOPICS LRT RENTAL BYLAW LPGA IN YOUR NEIGHBOURHOOD CITY PARENT FAMILY SHOW Home » News » Next stop: Northfield Station Wednesday, October, 23, 2013 - 9:09:58 AM Next stop: Northfield Station By James Jackson Chronicle Staff The first two tenants of a major new development in the city’s north end have been revealed. Cineplex Digital Solutions and MNP LLP will occupy nearly half of the space available at the new Northfield Station development located at 137 and 139 Northfield Dr. W. The project is located next to a proposed light rail transit station and just minutes from the expressway. Submitted Image The total project will cost an estimated The multi-million development dubbed Northfield Station, located at 139 $9 million. Northfield Dr. W. The Zehr Group believes the presence of a light rail transit stop will be a boon to the area in the north end of the city. “They always say ‘location, location, location,’ and I believe we have arguably one of the most interesting and best locations (in the city),” said Don Zehr, chief executive officer of The Zehr Group, the local developer responsible for the site. “If you don’t want to be right downtown, this is a really cool space to be in.” Cineplex will be moving from their current Waterloo location on McMurray Road and expanding to occupy the entire 14,600 square-foot office building at 137 Northfield Dr. -

At Advertising Specs

For additional advertising information, please contact your Corporate Account Representative at Metroland Corporate Sales 10 Tempo Ave., Toronto ON M2H 2N8 Advertising Specs Media Group Ltd. Tel: 416.493.1300 • Fax: 416.493.0623 Modular Sizes TABLOID FULL PAGE THREE QUARTER - H HALF - V HALF - H THREE EIGHTS - V QUARTER - V QUARTER - H 10.375” X 11.5” 10.375” X 8.571” 5.145” x 11.5” 10.375 x 5.71” 5.145” x 8.571” 5.145” x 5.71” 10.375” x 2.786” BASEBAR SIXTH - H EIGHTH - H (FRONT PAGE OR SECTION FRONT ONLY) SIXTEENTH - H SIXTEENTH - V THIRTYSECOND 5.145” x 3.714” 5.145” x 2.786” 10.375” x 1.785” 5.145” x 1.357” 2.54” x 2.786” 2.54” x 1.357” ALL TABLOID SIZES ABOVE CAN BE USED IN THE BROADSHEET FORMATS BROADSHEET B/S FULL PAGE B/S THREE QUARTER - H B/S HALF - V B/S HALF - H B/S THREE EIGHTS - V 10.375” x 21.5” 10.375” x 16.125” 5.145” x 21.5” 10.375 x 10.75” 5.145” x 16.125” B/S QUARTER - V B/S QUARTER - H B/S FIFTH - V B/S SIXTH - H B/S EIGHTH - H 5.145” x 10.75” 10.375” x 5.375” 5.145” x 8.8” 5.145” x 7.17” 5.145” x 5.285” Dailies Columns See reverse for Niagara Modules METROLAND DAILIES - HAMILTON SPECTATOR, GUELPH MERCURY AND WATERLOO REGION RECORD - BROADSHEET 1 col. 2 col. -

Recruitment and Classified Advertising in Both Community and Daily Newspapers

Recruitment and &ODVVL¿HG$GYHUWLVLQJ Rate Card January 2015 10 Tempo Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M2H 2N8 tel.: 416.493.1300 fax: 416.493.0623 e:DÀLQGHUV#PHWURODQGFRP www.millionsofreaders.com www.metroland.com METROLAND MEDIA GROUP LTD. AJAX/PICKERING - HAMILTON COMMUNITY METROLAND NEWSPAPERS EDITIONS FORMAT PRESS RUNS 1 DAY 2 DAYS 3 DAYS DEADLINES, CONDITIONS AND NOTES Ajax/ Pickering News Advertiser Wed Tab 54,400 3.86 1.96 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication Thurs Tab 54,400 Alliston Herald (Modular ad sizes only) Thurs Tab 22,500 1.45 1.20 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication Almaguin News Thurs B/S 4,600 0.75 Deadline: 3 Business Days prior to publication Ancaster News/Dundas Star Thurs Tab 30,879 1.25 Deadline: 3 Business Days prior to publication Arthur Enterprise News Wed Tab 900 0.61 Deadline: 3 Business Days prior to publication Barrie Advance/Innisfil/Journal Thurs Tab 63,800 2.95 2.33 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication (Modular ad sizes only) Belleville News Thurs Tab 23,715 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication Bloor West Villager Thurs Tab 34,300 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication Bracebridge Examiner Thurs Tab 8,849 1.40 Deadline: 3 Business Days prior to publication Bradford West Gwillimbury Topic Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication - Material & Thurs Tab 10,700 1.00 (Modular ad sizes only) Booking **Process Color add 25%, Spot add 15%, up to $350 Brampton Guardian/ Wed Tab 240,500 Deadline: 2 Business Days prior to publication. -

National Newspaper Awards Concours Canadien De Journalisme

NATIONAL NEWSPAPER AWARDS CONCOURS CANADIEN DE JOURNALISME FINALISTS/FINALISTES - 2012 Multimedia Feature/Reportage multimédia Investigations/Grande enquête La Presse, Montréal The Canadian Press Steve Buist, Hamilton Spectator The Globe and Mail Isabelle Hachey, La Presse, Montréal Winnipeg Free Press Huffington Post team David Bruser, Jesse McLean, Toronto Star News Feature Photography/Photographie de reportage d’actualité Arts and Entertainment/Culture Tyler Anderson, National Post Aaron Elkaim, The Canadian Press J. Kelly Nestruck, The Globe and Mail Lyle Stafford, Victoria Times-Colonist Stephanie Nolen, The Globe and Mail Sylvie St-Jacques, La Presse, Montreal Beats/Journalisme spécialisé Sports/Sport Jim Bronskill, The Canadian Press Sharon Kirkey, Postmedia News David A. Ebner, The Globe and Mail Heather Scoffield, The Canadian Press Dave Feschuk, Toronto Star Mary Agnes Welch, Winnipeg Free Press Roy MacGregor, The Globe and Mail Explanatory work/Texte explicatif Feature Photography/Photographie de reportage James Bagnall, Ottawa Citizen Tyler Anderson, National Post Ian Brown, The Globe and Mail Peter Power, The Globe and Mail Mary Ormsby, Toronto Star Tim Smith, Brandon Sun Politics/Politique International /Reportage à caractère international Linda Gyulai, The Gazette, Montreal Agnès Gruda, La Presse, Montréal Stephen Maher, Glen McGregor, Postmedia News/The Ottawa Michèle Ouimet, La Presse, Montréal Citizen Geoffrey York, The Globe and Mail Peter O’Neil, The Vancouver Sun Editorials/Éditorial Short Features/Reportage bref David Evans, Edmonton Journal Erin Anderssen, The Globe and Mail Jordan Himelfarb, Toronto Star Jayme Poisson, Toronto Star John Roe, Waterloo Region Record Lindor Reynolds, Winnipeg Free Press Editorial Cartooning/Caricature Local Reporting/Reportage à caractère local Serge Chapleau, La Presse, Montréal Cam Fortems, Michele Young, Kamloops Daily News Andy Donato, Toronto Sun Susan Gamble, Brantford Expositor Brian Gable, The Globe and Mail Barb Sweet, St. -

City of Kitchener 2021 Business Plan Contents 2021 Business Plan

C ITY OF KITCHENER 2021 BUSINESS PLAN Our corporate mission Our community vision Proudly providing valued services for Together, we will build an innovative, our community. caring and vibrant Kitchener. City of Kitchener 2021 Business Plan Contents 2021 Business Plan ........................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Pursuing Our Vision, Fulfilling Our Mission ................................................................................................. 4 Structure .................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Sharing Our Results ............................................................................................................................................... 5 2019-2022 Strategic Plan Action Statements ............................................................................ 6 People-Friendly Transportation ........................................................................................................................ 6 Environmental Leadership .................................................................................................................................. 8 Vibrant Economy ................................................................................................................................................ -

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 / Bryce Kraeker 1 PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2016 / President

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 / Bryce Kraeker 1 PRESIDENT’S REPORT 2016 / President \ Looking back, and looking forward… A milestone is commonly defined as a In looking towards the future, the At the opening of the Gallery on significant or important event in the life, Gallery launched a special anniversary September 21, 1956, the first President progress or development of a person fundraising campaign, which we of the Board, Gerald Eastman, or organization. 2016 was certainly called “60 for 60”. The goal was to expressed the vision of the Founders in a milestone year for the Kitchener- raise $60,000 in honour of our 60th establishing a gallery with the purpose Waterloo Art Gallery. anniversary, with funds earmarked of showing the “art of today”. He stated to support one of our key strategic that, “it is our conviction that art is for With the celebration of its 60th priorities: the growth of our public all people in the community. An art anniversary, the Gallery took the time programming with a view to engaging gallery, in our opinion, should be an to both reflect on its founding legacy the next generation of art lovers in our activity in which we can all be members and focus on its future vision. We increasingly diverse community. The and participate fully just as we do in revisited the stories of the Gallery’s 60 for 60 Campaign was enthusiastically our schools and in our churches”. These early Founders, a group of community embraced by the community and words remain as true today as they did builders with access to a bicycle shed to date, we have raised $175,000. -

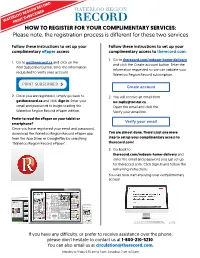

HOW to REGISTER for YOUR COMPLIMENTARY SERVICES: Please Note, the Registration Process Is Different for These Two Services

WATERLOOPRINT REGIONSUBSCRIBER RECORD HOW TO REGISTER FOR YOUR COMPLIMENTARY SERVICES: Please note, the registration process is different for these two services Follow these instructions to set up your Follow these instructions to set up your complimentary ePaper access: complimentary access to therecord.com: 1. Go to therecord.com/redeem-home-delivery 1. Go to gettherecord.ca and click on the and click the Create account button. Enter the Print Subscriber button. Enter the information information requested so we can validate your requested to verify your account. Waterloo Region Record subscription. PRINT SUBSCRIBER Create account 2. Once you are registered, simply go back to 2. You will receive an email from gettherecord.ca and click Sign in. Enter your [email protected]. email and password to begin reading the Open the email and click the Waterloo Region Record ePaper edition. Verify your email link. Prefer to read the ePaper on your tablet or smartphone? Verify your email Once you have registered your email and password, download the Waterloo Region Record ePaper app You are almost done. There’s just one more from the App Store or GooglePlay by searching step to set up your complimentary access to “Waterloo Region Record ePaper”. therecord.com! 3. Go back to therecord.com/redeem-home-delivery and enter the email and password you just set up for therecord.com. Click Sign in and follow the remaining instructions. You can now start enjoying your complimentary access! Isolated showers High 16 Details, B12 TUESDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2019 SERVING KITCHENER, WATERLOO, CAMBRIDGE AND THE TOWNSHIPS Community Waterloo and Cambridge now centres sit candidates for cannabis shops empty, but groups can’t access space Kitchener’s recreation staff outlines proposed changes to policies CATHERINE THOMPSON WATERLOO REGION RECORD KITCHENER — Many community groups have trouble getting ac- cess to meeting rooms, gyms and other space at Kitchener community centres, even though the centres sit empty the vast majority of the time. -

REGIONAL COUNCIL MINUTES Wednesday, June 28, 2006

REGIONAL COUNCIL MINUTES Wednesday, June 28, 2006 The following are the minutes of the Regular Council meeting held at 7:15 p.m. in the Regional Council Chamber, 150 Frederick Street, Kitchener, Ontario, with the following members present: Chair K. Seiling, J. Brewer, D. Craig, K. Denouden, T. Galloway, R. Kelterborn, C. Millar, J. Mitchell, W. Roth, J. Smola, B. Strauss, J. Wideman, and C. Zehr. Regrets: M. Connolly, H. Epp, J. Haalboom DECLARATIONS OF PECUNIARY INTEREST UNDER THE MUNICIPAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST ACT None declared. Chair Seiling noted 2 plaques that have been received and circulated them to councillors. One was recognizing the Region’s commitment to the Canadian Forces Reserves and the other was with respect to the Greater Golden Horseshoe Growth Plan. CLOSED SESSION MOVED by W. Roth SECONDED by J. Brewer That a closed meeting of Council be held on Wednesday, June 28, 2006 at 6:30 p.m. in accordance with Section 239 of the Municipal Act, 2001, for the purposes of considering the following subject matters: a) pending acquisition of property b) personal matters about an identifiable individual c) solicitor-client privilege d) labour negotiations e) labour relations CARRIED MOVED by J. Smola SECONDED by K. Denouden The Council reconvene in Open Session. CARRIED DELEGATIONS a) Catherine Fife appeared before Council with respect to the Best Start Program and provided her views on the proposed Option 1. She suggested amendments to the option in order to accommodate the special needs children and ensure continued funding for their programs. She stated by not increasing the funding there will be a Council - 2 - 06/06/28 decrease in the services provided. -

Theatre Is... Occupation

theatre is... OCCUPATION theatre is here SEPTEMBER WATERLOO REGION2429 FESTIVAL PROGRAMME INTERNATIONAL MULTICULTURAL PLATFORM for ALTERNATIVE CONTEMPORARY THEATRE Artistic Director’s Message We say in Arabic “the third is the most stable.” This is a traditional saying that means the first two trials are usually subject to errors and experimentation, but by the time you get to the third, you should know damn well what you are doing! Tickets My friends and colleagues, my gracious and generous IMPACT PROGRAMMING community—welcome to the “third” IMPACT festival. IMPACT 13 PASS $113 includes admission to all ticketed IMPACT events / Limited Avail. Welcome to IMPACT 13! GENERAL ADMISSION $20 in advance / $25 at the door IMPACT 13 presents to you theatre as occupation. It brings us STUDENTS/SENIORS $15 in advance / $20 at the door together with people whose main occupation is to challenge, create and inspire. It connects us with individuals who make ORPHEUS & EURYDICE $15 General Admission / $10 Students/Seniors theatre under occupation. It invites us to engage with artists BALANCING ON MOONBEAMS $10 General Admission / $7 Children whose work occupies vital spaces in their people’s, nation’s or community’s consciousness. IMPACT CONFERENCE – STAGING OCCUPATION This year Kitt Johnson’s riveting and naked DRIFT or drive occupies the stage like a bullet knocking down our civilized and cultured veneers. The racialized bodies of the Afro-Colombian IMPACT 13 CONFERENCE PASS $160 (includes registration and admission to all ticketed IMPACT events / Limited Avail.) Sankofa occupy and free themselves from La Ciudad de los Otros / City of Others. The Global All prices include HST. -

2019 Newsletters

Waterloo Historical Society Newsletter MARCH 2019 Marion Roes, Editor Public Meetings – All are welcome! Saturday, April 6, 1 pm Victoria Park Pavilion Doors Open at 12 80 Schneider Ave., Kitchener Please bring indoor footwear to wear if wet weather Our presenter for this meeting will be Tarah Brookfield. Tarah is a graduate of McGill University (BA), University of Waterloo (MA), and York University (PhD). Since 2009, she has been a professor of history and youth and children’s studies at Wilfrid Laurier University’s Brantford campus. Tarah’s past and current research focuses on Canadian women’s political activism, peace work, and child welfare efforts during the World Wars and Cold War. She is the author of Cold War Comforts: Canadian Women, Child Safety, and Global Insecurity (2012). She’ll be presenting on research conducted for her second book, Our Voices Must be Heard: Women and the Vote in Ontario (2018) which examines the history of suffrage activism, anti- suffragists, and Ontario’s first women voters, including some stories of women from what is now the Waterloo Region. Tarah will have her books to sell at the meeting. Next meetings Victoria Park Pavilion: Tuesday, May 21 at 7:30 pm, doors open at 6:30 Volumes will be distributed free to current members at this meeting. Note: There won’t be another newsletter before the May 21 meeting. Details will be on our web site, Facebook and Twitter. If you don’t use the internet and would like information, contact Eric Uhlmann after May 13 at the phone number on the back page. -

REGIONAL COUNCIL MINUTES Wednesday, January 26, 2005

REGIONAL COUNCIL MINUTES Wednesday, January 26, 2005 The following are the minutes of the Regular Council meeting held at 7:10 p.m. in the Regional Council Chamber, 150 Frederick Street, Kitchener, Ontario, with the following members present: Chair K. Seiling, J. Brewer, M. Connolly, K. Denouden, H. Epp, T. Galloway, J. Haalboom, R. Kelterborn, C. Millar, J. Mitchell, J. Smola, B. Strauss, J. Wideman, and C. Zehr. Regrets: D. Craig and W. Roth DECLARATIONS OF PECUNIARY INTEREST UNDER THE MUNICIPAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST ACT J. Smola disclosed a pecuniary interest with respect to the grant for K-W Counselling Services Inc., as he is the carpenter for this new construction. CLOSED SESSION MOVED by B. Strauss SECONDED by J. Smola That Council convene in Closed Session pursuant to Part II, Section 14(1) a), b), f) of Procedural By-law 00-031, as amended. CARRIED DELEGATIONS Mike O’Connor on behalf of Keith Murray appeared with respect to the Development Charges Act, 1997. M. O’Connor stated he is Mr. Murray’s son-in-law and he supports a change in the Development Charges By-law. He stated this proposed development of Mr. Murray’s land will require no increase in the current Regional infrastructure. Mr. O’Connor concurred that the Council’s hands are tied but noted the building is primarily for the production of crops and breeding of animals. He advised the property is used for a farm vacation program for 60 days each year. He provided suggestions to Council for changes in the wording of the by-law which would give Council the power to impose development charges based on a percentage of use related to time or square footage.