Scoping Study Into Potential Development Opportunities for Dundee Airport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Travelling Made Easy…

Travelling made easy… Guidance and information on Travelling Safely in the UK and Scotland Follow government guidance on travelling safely in the UK and Scotland • Fly Safe with Loganair - Simple Steps to Healthy Flying • Dundee Airport - Information for Passengers • London City Airport - Safe, Careful, Speedy Journeys • Heathrow Airport - Fly Safe • Edinburgh Airport - Let's all Fly Safe • Glasgow Airport - Helping Each Other to Travel Safely • Aberdeen Airport - Helping Each Other to Travel Safely • Network Rail - Let's Travel Safely Fly into Dundee Dundee has a twice daily service from Dundee Airport to London City, which serves around 50 international destinations as well as a non-stop service between Dundee and Belfast City, serving 18 destinations including Amsterdam, with up to 12 flights per week and is a 5 minute drive from the city centre. A taxi rank is located just outside the airport. Discounted Flights to / from Dundee from London City or Belfast Loganair is offering up to 30% off flights to delegates travelling to/from Dundee from London City or Belfast for this conference. Please book at Loganair.co.uk before 16 April 2021, quoting promotional code 'SBNS2021' at the time of booking, for travel between 10 – 18 April 2021. Please click here to book. View airport and flight options here - http://www.hial.co.uk/dundee-airport/. To book visit Loganair International Flights are available to/from Scotland’s other major cities Fly into Aberdeen International Airport Connects with 50 international destinations and a 1 hour 30 minute drive from Dundee View airport and flight options here: https://www.aberdeenairport.com/ How to get to Dundee from the Airport TAXI/PRIVATE Discounted fares to/from Aberdeen International Airport, click here HIRE DIRECT BY TRAIN Aberdeen International Airport is about 11 kilometres from Aberdeen Railway Station, you can get there by hiring a taxi OR catching a bus in less than 30 minutes. -

Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean

Friday 3 November 2017 Business Bulletin Iris Ghnothaichean Today's Business Meeting of the Parliament Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. There are no meetings today. Friday 3 November 2017 1 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Meeting of the Parliament There are no meetings today. Friday 3 November 2017 2 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Committees | Comataidhean Committee Meetings There are no meetings today. Friday 3 November 2017 3 Today's Business Future Business Motions & Questions Legislation Other Gnothaichean an-diugh Gnothaichean ri teachd Gluasadan agus Ceistean Reachdas Eile Chamber | Seòmar Future Meetings of the Parliament Business Programme agreed by the Parliament on 1 November 2017 Tuesday 7 November 2017 2:00 pm Time for Reflection - Dr Jonathan Reyes, Executive Director of the Department of Justice, Peace and Human Development for the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Washington, DC, and former President and CEO of Catholic Charities in the Archdiocese of Denver, Colorado followed by Parliamentary Bureau Motions followed by Topical Questions (if selected) followed by First Minister Statement: Apology to those convicted for same-sex sexual activity that is now legal followed by Stage 1 Debate: Forestry and Land Management (Scotland) Bill followed -

Dundee and Perth

A REPUTATION FOR EXCELLENCE Volume 3: Dundee and Perth Introduction A History of the Dundee and Perth Printing Industries, is the third booklet in the series A Reputation for Excellence; others are A History of the Edinburgh Printing Industry (1990) and A History of the Glasgow Printing Industry (1994). The first of these gives a brief account of the advent of printing to Scotland: on September 1507 a patent was granted by King James IV to Walter Chepman and Andro Myllar ‘burgessis of our town of Edinburgh’. At His Majesty’s request they were authorised ‘for our plesour, the honour and profitt of our realme and liegis to furnish the necessary materials and capable workmen to print the books of the laws and other books necessary which might be required’. The partnership set up business in the Southgait (Cowgate) of Edinburgh. From that time until the end of the seventeenth century royal patents were issued to the trade, thus confining printing to a select number. Although there is some uncertainty in establishing precisely when printing began in Dundee, there is evidence that the likely date was around 1547. In that year John Scot set up the first press in the town, after which little appears to have been done over the next two centuries to develop and expand the new craft. From the middle of the eighteenth century, however, new businesses were set up and until the second half of the present century Dundee was one of Scotland's leading printing centres. Printing in Perth began in 1715, with the arrival there of one Robert Freebairn, referred to in the Edinburgh booklet. -

Flying Clubs and Schools

A P 3 IR A PR CR 1 IC A G E FT E S, , YOUR COMPLE TE GUI DE C CO S O U N R TA S C ES TO UK AND OVERSEAS UK clubs TS , and schools Choose your region, county and read down for the page number FLYING CLUBS Bedfordshire . 34 Berkshire . 38 Buckinghamshire . 39 Cambridgeshire . 35 Cheshire . 51 Cornwall . 44 AND SCHOOLS Co Durham . 53 Cumbria . 51 Derbyshire . 48 elcome to your new-look Devon . 44 Dorset . 45 Where To Fly Guide listing for Essex . 35 2009. Whatever your reason Gloucestershire . 46 Wfor flying, this is the place to Hampshire . 40 Herefordshire . 48 start. We’ve made it easier to find a Lochs and Hertfordshire . 37 school and club by colour coding mountains in Isle of Wight . 40 regions and then listing by county – Scotland Kent . 40 Grampian Lancashire . 52 simply use the map opposite to find PAGE 55 Highlands Leicestershire . 48 the page number that corresponds Lincolnshire . 48 to you. Clubs and schools from Greater London . 42 Merseyside . 53 abroad are also listed. Flying rates Tayside Norfolk . 38 are quoted by the hour and we asked Northamptonshire . 49 Northumberland . 54 the schools to include fuel, VAT and base Fife Nottinghamshire . 49 landing fees unless indicated. Central Hills and Dales Oxfordshire . 42 Also listed are courses, specialist training Lothian of the Shropshire . 50 and PPL ratings – everything you could North East Somerset . 47 Strathclyde Staffordshire . 50 Borders want from flying in 2009 is here! PAGE 53 Suffolk . 38 Surrey . 42 Dumfries Northumberland Sussex . 43 The luscious & Galloway Warwickshire . -

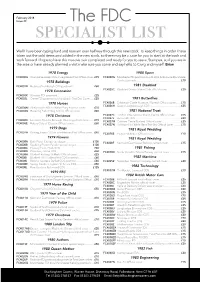

The FDC Specialist List

February 2018 Issue 29 The FDC specialist list Well I have been typing hard and now am over half way through this new stock. To keep things in order I have taken out the sold items and added in the new stock, so there may be a case for you to start at the back and work forward. I hope to have this massive task completed and ready for you to see at Stampex, so if you are in the area or have already planned a visit make sure you come and say hello to Craig and myself. Brian 1978 Energy 1980 Sport FC4000A Coalville Leicester CDS on registered Post Office cover ..£75 FC4022G Manchester FDI postmark plus St John Ambulance Manchester 1978 Buildings Centre postmark ................................................................£10 FC4001D Holyrood Edinburgh CDS postmark ..............................£60 1981 Disabled 1978 Coronation FC4025C Disabled Drivers Motor Club official cover ....................£35 FC4003K Windsor FDI postmark .....................................................£25 FC4003L Crewe FDI postmark on Sandbach First Day Cover......£25 1981 Butterflies 1978 Horses FC4026B Exhibition Castle Museum, Norwich Official cover .......£15 FC4026H Quorn Loughborough CDS ............................................£25 FC4004M Aberystwyth FDI on Welsh Pony Express cover ............£35 FC4004Q Havering Park Riding School official cover ....................£40 1981 National Trust 1978 Christmas FC4027C London International Stamp Centre official cover ........£15 FC4027L Barmouth CDS .................................................................£20 -

M84 HSUK Scottish Infrastructure Diagram

HIGH SPEED UK © NETWORK 2019 Inverness Elgin 2020 SCOTLAND & NORTH COUNTRY KEY INFRASTRUCTURE HSUK operating on…. Aviemore Aberdeen New high speed line Tunnel >5km long Stonehaven Restored line Pitlochry Upgraded line Forfar New conventional line Montrose Perth Existing line Dundee New/modified/existing station served by HSUK Glenfarg line restored to re-engineered alignment Other main line route MB Middlesbrough Stirling Kirkcaldy SR Sunderland Edinburgh Airport Glasgow Edinburgh Motherwell Berwick Galashiels Kilmarnock Ayr Alnmouth HSUK platforms on new Lockerbie Northumbria Bridge, travelator-linked to Dumfries existing Newcastle Stn Carlisle Newcastle SR Durham Penrith MB HSUK Darlington TRUNK ROUTE Oxenholme Northallerton York-Darlington ECML generally upgraded to 4-track for higher York Lancaster speed & capacity York bypass not shown WCML to Birmingham HSUK to Northern cities, and London Midlands cities & London HIGH SPEED UK Inverness Elgin © NETWORK2020 2019 SCOTLAND & NORTH COUNTRY PROPOSED HIGH SPEED SERVICES Aviemore Aberdeen (served by 32 all trains except 91) Stonehaven 91 Dotted black line Pitlochry Forfar 32 38 indicates regional Montrose services Dashed green line represents service Perth 32 at 2-hour frequency Dundee Each solid line represents a single 32 hourly service in 91 38 each direction. Stirling 38 denotes HSUK Kirkcaldy service HSUK38 Glasgow Edinburgh Airport Station served/ not served by all 21 Edinburgh services illustrated. 38 91 34 Station served only 31 01 by regional services. 02 04 Berwick Motherwell -

Edinburgh Waverley Dundee

NETWORK RAIL Scotland Route SC171 Edinburgh Waverley and Dundee via Kirkcaldy (Maintenance) Not to Scale T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.2.0 November 2015 ©Network Rail / T.A.P.Ltd. 2010 MAINTENANCE DWG No:090 Version 2.0 Contents Legend Page 111 T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1 March 2007 Page 1V T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1 March 2007 Route Page 1 Edinburgh Waverley Station T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1.1 March 2008 Page 2 Mound Tunnels T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1.1 March 2008 Page 3 Haymarket Tunnels T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1.1 March 2008 Page 4 Haymarket East Junction T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1.2 April 2008 Mileage format changed Page 5 Haymarket Central Junction T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1.1 March 2008 Page 6 Haymarket West Junction T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1.4 April 2015 Signal Ammended Page 7 South Gyle Station T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1.2 April 2015 Signals Ammended Page 8 Almond Viaduct T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1.1 April 2015 Signals Ammended/Station Added Page 9 Dalmeny Junction T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1.3 November 2015 Point Numbers Altered Page 10 Forth Bridge T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1.2 April 2015 Signals Ammended Page 11 Inverkeithing Tunnel T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1.1 April 2015 Signals Ammended Page 12 Dalgety Bay Station T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1 March 2007 Page 13 Aberdour Station T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1 March 2007 Page 14 Burntisland T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1 March 2007 Map as per DVD Page 15 Kinghorn Tunnel T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1 March 2007 Page 16 Invertiel Viaduct T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1 March 2007 Page 17 Kirkcaldy Station T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1 March 2007 Page 18 Thornton South Junction T.A.P.M.SC171.0.0.0.1 -

Economic and Social Impact of Inverness Airport

www.hie.co.uk ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL IMPACT OF INVERNESS AIRPORT Final Report September 2018 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 2 Background to the study 2 Study objectives 2 Study methodology 2 Study contents 3 2 Overview of Inverness Airport and Air Service Activity 4 Introduction 4 Evolution of Inverness Airport 4 Trends in activity 5 Scheduled route analysis 8 Measuring global business connectivity 14 Passenger leakage from Inverness catchment area 16 3 Quantified Economic Impact Assessment 18 Introduction 18 On-site impacts 18 Inbound visitor impacts 22 Valuation of passenger time savings 24 4 Wider Catalytic and Social Impacts 26 Introduction 26 Contribution to economic growth 27 The airport services 28 Business impacts 30 Social impacts 32 Future priorities for the airport and services 33 5 Summary of Findings 36 Introduction 36 Summary of findings 36 Appendices 38 Appendix 1: EIA Methodology and Workings 39 Appendix 2: List of Consultees 41 Appendix 3: Measuring Global Connectivity 42 Introduction 42 Direct flights 42 Onward connections 43 Fit of Inverness air services with Growth Sector requirements 46 Appendix 4: Inbound Visitor Impacts 49 Introduction 49 Visitor expenditures 50 Gross economic impacts 52 Appendix 5: Valuation of Passenger Time Savings 54 Approach 54 i 1 INTRODUCTION BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY 1.1 ekosgen, in partnership with Reference Economic Consultants, was commissioned by Highlands and Islands Enterprise (HIE) and Highlands and Islands Airports Limited (HIAL) to undertake an economic and social impact study of Inverness Airport. 1.2 Inverness Airport is the principal airport in the Highlands and Islands and the fourth busiest in Scotland. -

Aberdeen | Dundee | Edinburgh

Aberdeen | Dundee | Edinburgh daily P PP route number M9 M90 M92 M11 M92 M9 M90 M92 M9 M90 M9 M92 M92 M9 M92 M92 Aberdeen Union Square Bus Station 0600 0705 0745 0835 0845 0945 1045 1145 1245 Forfar A90 Underpass McDonalds x x x x 0945 x 1145 x x Dundee Seagate Bus Station arr 0720 0840 0915 1000 1012 1110 1212 1310 1410 Dundee Seagate Bus Station dep 0605 0725 v 0845 0920 1005 1015 v 1115 1215 v 1315 1415 0640 0955 1050 CONNECT Perth Broxden Park & Ride arr Perth Broxden Park & Ride dep v 0645 x x v 1000 v 1100 x x x Kinross Park & Ride 0710 0808 0928 1025 1125 1158 1258 1358 Halbeath Park & Ride arr 0724 0822 0942 1039 1139 1212 1312 1412 Halbeath Park & Ride dep 0724 0822 0942 1042 1142 1212 1312 1412 Edinburgh Barnton Jct 0746 0844 1002 1102 1202 1232 1332 1432 Edinburgh Queensferry St 0758 0854 1012 1112 x 1212 1242 1342 1442 x Edinburgh Bus Station 0810 0904 1020 1120 1133 1220 1250 1350 1450 1543 daily P P PPP P route number M9 M90 M9 M92 M92 M9 M92 M92 M9 M91 M9 M90 M92 M9 M90 M92 Aberdeen Union Square Bus Station 1245 1345 1445 1545 1645 1645 1745 1845 1945 2045 Forfar A90 Underpass McDonalds x 1445 x 1645 x x 1845 x x x Dundee Seagate Bus Station arr 1410 1512 1610 1715 1810 1810 1915 2010 2110 2210 Dundee Seagate Bus Station dep 1415 v 1515 1615 v 1725 1815 1815 1920 2015 2120 2215 1450 1850 1955 2050 2150 CONNECT Perth Broxden Park & Ride arr Perth Broxden Park & Ride dep v 1500 x x x v 1900 v 2000 2055 v 2155 x Kinross Park & Ride 1525 1558 1700 1810 1925 2035 x 2220 2258 Halbeath Park & Ride arr 1539 1615 1715 1825 1939 -

X58 Dundee - Cupar - Leven - Kirkcaldy - Dalgety Bay - Edinburgh Revised Stopping Arrangements; All Stops Between Leven and Ferrytoll

X58 Dundee - Cupar - Leven - Kirkcaldy - Dalgety Bay - Edinburgh Revised Stopping Arrangements; All stops between Leven and Ferrytoll Special Service X58 X58 X58 X58 X58 X58 X58 X58 X58 Daily Dundee bus station 1005 1205 1405 1605 1805 2005 Balmullo post office 1020 1220 1420 1620 1820 2020 Dairsie Pitcairn Park 1024 1224 1424 1624 1824 2024 Cupar rail station 0732 1032 1232 1432 1632 1832 2032 Ceres Bow Butts 0741 1041 1241 1441 1641 1841 2041 Craigrothie village hall 0745 1045 1245 1445 1645 1845 2045 Bonnybank Cupar Road 0653 0753 1053 1253 1453 1653 1853 2053 Kennoway shopping centre 0656 0756 1056 1256 1456 1656 1856 2056 Leven bus station 4 arr 0703 0806 1106 1306 1506 1706 1906 2106 Leven bus station 4 dep 0710 0810 0910 1110 1310 1510 1710 Aberhill bus depot 0712 0812 0912 1112 1312 1512 1712 Toll Bar Methilhaven Road 0714 0814 0914 1114 1314 1514 1714 East Wemyss School Wynd 0723 0823 0923 1123 1323 1523 1723 Dysart Porte 0730 0830 0930 1130 1330 1530 1730 Kirkcaldy bus station arr 0740 0840 0940 1140 1340 1540 1740 Kirkcaldy bus station 5 dep 0743 0943 1143 1343 1543 1743 Dalgety Bay opp Pentland Rise 0801 1001 1201 1401 1601 1801 Dalgety Bay The Bridges 0806 1006 1206 1406 1606 1806 Dalgety Bay Forth Reach 0808 1008 1208 1408 1608 1808 Inverkeithing Hope Street 0814 1014 1214 1414 1614 1814 Ferrytoll park & ride 1 0818 1018 1218 1418 1618 1818 Forth Road Bridge south exit 0822 1022 1222 1422 1622 1822 Blackhall Queensferry Road 0833 1033 1233 1433 1633 1833 West End Queensferry Street 0844 1044 1244 1444 1644 1844 Edinburgh -

Dundee Airport

8 RTP/14/13 TAYSIDE AND CENTRAL SCOTLAND TRANSPORT PARTNERSHIP 17JUNE 2014 DUNDEE AIRPORT REPORT BY PROJECTS MANAGER This report outlines the content and recommendations of the Transport Scotland research study “Scoping Study into Potential Development Opportunities for Dundee Airport” and informs the Partnership of Tactran Officer participation in an associated Steering Group. 1 RECOMMENDATIONS 1.1 That the Partnership :- (i) notes and comments on the contents and recommendations of the Transport Scotland research study “Scoping Study into Potential Development Opportunities for Dundee Airport”, as outlined within this report; and (ii) notes Tactran Officer participation in the Steering Group and agrees to receive a further update at a future meeting. 2 BACKGROUND 2.1 Tactran’s Regional Transport Strategy (RTS) recognises the strategic and economic importance of direct regional air connections to key UK and onward international destinations from Dundee Airport and states that Tactran will seek to enhance the economic prosperity of the region by working with airport authorities and others to promote and improve flights and facilities at Dundee Airport. 2.2 Recognising the importance attached to Dundee Airport within the RTS, the Partnership has on a number of occasions allocated funding to promoting and maintaining air services. At its meeting on 14 December 2010 the Partnership agreed to allocate £50,000 as a contribution to maintaining air services between Dundee and London (Report RTP/10/42 refers). At its meeting on 11 September 2012 the Partnership endorsed the allocation of £5,000 as a contribution towards a marketing campaign aimed at promoting Dundee Airport and improving the viability of air services and connections that operate from the airport (Report RTP/12/22 refers). -

Piper PA-28-140 Cherokee, G-BHXK No & Type of Engines

AAIB Bulletin: 1/2016 G-BHXK EW/C2015/04/01 ACCIDENT Aircraft Type and Registration: Piper PA-28-140 Cherokee, G-BHXK No & Type of Engines: 1 Lycoming O-320-E2A piston engine Year of Manufacture: 1965 (Serial no: 28-21106) Date & Time (UTC): 4 April 2015 at 1030 hrs Location: Near Loch Etive, Oban, Argyll and Bute Type of Flight: Private Persons on Board: Crew - 1 Passengers - 1 Injuries: Crew - 1 (Fatal) Passengers - 1 (Fatal) Nature of Damage: Aircraft destroyed Commander’s Licence: Private Pilot’s Licence Commander’s Age: 28 years Commander’s Flying Experience: 150 hours1 (of which 100 were on type) Last 90 days - 62 hours Last 28 days - 19 hours Information Source: AAIB Field Investigation Synopsis The aircraft was on a private flight from Dundee Airport to Tiree Airport. While established in the cruise at an altitude of 6,500 ft it entered a gentle right turn, the rate of which gradually increased with an associated high rate of descent and increase in airspeed. The aircraft struck the western slope of a mountain, Beinn nan Lus, in a steep nose-down attitude. Both persons on board were fatally injured. No specific cause for the accident could be identified but having at some point entered IMC, the extreme aircraft attitudes suggest that the pilot was experiencing some form of spatial disorientation and the recorded data and impact parameters suggest that the accident followed a loss of control, possibly in cloud. History of the flight The pilot had arranged to fly to Tiree with his wife for a family visit, departing on Saturday, 4 April, the day of the accident, and returning on Monday evening.