Darfur Cover.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 Highlights

Sudan Humanitarian Situation Report No. 19 Q3 2020 UNICEF and partners assess damage to communities in southern Khartoum. Sudan was significantly affected by heavy flooding this summer, destroying many homes and displacing families. @RESPECTMEDIA PlPl Reporting Period: July-September 2020 Highlights Situation in Numbers • Flash floods in several states and heavy rains in upriver countries caused the White and Blue Nile rivers to overflow, damaging households and in- 5.39 million frastructure. Almost 850,000 people have been directly affected and children in need of could be multiplied ten-fold as water and mosquito borne diseases devel- humanitarian assistance op as flood waters recede. 9.3 million • All educational institutions have remained closed since March due to people in need COVID-19 and term realignments and are now due to open again on the 22 November. 1 million • Peace talks between the Government of Sudan and the Sudan Revolu- internally displaced children tionary Front concluded following an agreement in Juba signed on 3 Oc- tober. This has consolidated humanitarian access to the majority of the 1.8 million Jebel Mara region at the heart of Darfur. internally displaced people 379,355 South Sudanese child refugees 729,530 South Sudanese refugees (Sudan HNO 2020) UNICEF Appeal 2020 US $147.1 million Funding Status (in US$) Funds Fundi received, ng $60M gap, $70M Carry- forward, $17M *This table shows % progress towards key targets as well as % funding available for each sector. Funding available includes funds received in the current year and carry-over from the previous year. 1 Funding Overview and Partnerships UNICEF’s 2020 Humanitarian Action for Children (HAC) appeal for Sudan requires US$147.11 million to address the new and protracted needs of the afflicted population. -

The Economics of Ethnic Cleansing in Darfur

The Economics of Ethnic Cleansing in Darfur John Prendergast, Omer Ismail, and Akshaya Kumar August 2013 WWW.ENOUGHPROJECT.ORG WWW.SATSENTINEL.ORG The Economics of Ethnic Cleansing in Darfur John Prendergast, Omer Ismail, and Akshaya Kumar August 2013 COVER PHOTO Displaced Beni Hussein cattle shepherds take shelter on the outskirts of El Sereif village, North Darfur. Fighting over gold mines in North Darfur’s Jebel Amer area between the Janjaweed Abbala forces and Beni Hussein tribe started early this January and resulted in mass displacement of thousands. AP PHOTO/UNAMID, ALBERT GONZALEZ FARRAN Overview Darfur is burning again, with devastating results for its people. A kaleidoscope of Janjaweed forces are once again torching villages, terrorizing civilians, and systematically clearing prime land and resource-rich areas of their inhabitants. The latest ethnic-cleans- ing campaign has already displaced more than 300,000 Darfuris this year and forced more than 75,000 to seek refuge in neighboring Chad, the largest population displace- ment in recent years.1 An economic agenda is emerging as a major driver for the escalating violence. At the height of the mass atrocities committed from 2003 to 2005, the Sudanese regime’s strategy appeared to be driven primarily by the counterinsurgency objectives and secondarily by the acquisition of salaries and war booty. Undeniably, even at that time, the government could have only secured the loyalty of its proxy Janjaweed militias by allowing them to keep the fertile lands from which they evicted the original inhabitants. Today’s violence is even more visibly fueled by monetary motivations, which include land grabbing; consolidating control of recently discovered gold mines; manipulating reconciliation conferences for increased “blood money”; expanding protection rackets and smuggling networks; demanding ransoms; undertaking bank robberies; and resum- ing the large-scale looting that marked earlier periods of the conflict. -

North Darfur II

Darfur Humanitarian Profile Annexes: I. North Darfur II. South Darfur III. West Darfur Darfur Humanitarian Profile Annex I: North Darfur North Darfur Main Humanitarian Agencies Table 1.1: UN Agencies Table 1.2: International NGOs Table 1.3: National NGOs Intl. Natl. Vehicl Intl. Natl. Vehic Intl. Natl. Vehic Agency Sector staff staff* es** Agency Sector staff staff* les** Agency Sector staff staff les FAO 10 1 2 2 ACF 9 4 12 3 Al-Massar 0 1 0 Operations, Logistics, Camp IOM*** Management x x x GAA 1, 10 1 3 2 KSCS x x x OCHA 14 1 2 3 GOAL 2, 5, 8, 9 6 117 10 SECS x x x 2, 3, 7, UNDP*** 15 x x x ICRC 12, 13 6 20 4 SRC 1, 2 0 10 3 2, 4, 5, 6, UNFPA*** 5, 7 x x x IRC 9, 10, 11 1 5 4 SUDO 5, 7 0 2 0 Protection, Technical expertise for UNHCR*** site planning x x x MSF - B 5 5 10 0 Wadi Hawa 1 1 x 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, Oxfam - UNICEF 9 11, 12 4 5 4 GB 2, 3, 4 5 30 10 Total 1 14 3 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, UNJLC*** 17 x x x SC-UK 11, 12 5 27 8 Technical Spanish UNMAS*** advice x x x Red Cross 3, 4 1 0 1 UNSECOORD 16 1 1 1 DED*** x x x WFP 1, 9, 11 1 12 5 NRC*** x x x WHO 4, 5, 6 2 7 2 Total 34 224 42 Total 10 29 17 x = information unavailable at this time Sectors: 1) Food 2) Shelter/NFIs 3) Clean water 4) Sanitation 5) Primary Health Facilities *Programme and project staff only. -

SUDAN Price Bulletin August 2021

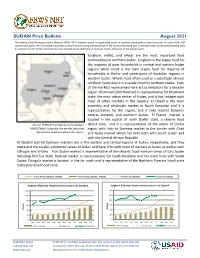

SUDAN Price Bulletin August 2021 The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) monitors trends in staple food prices in countries vulnerable to food insecurity. For each FEWS NET country and region, the Price Bulletin provides a set of charts showing monthly prices in the current marketing year in selected urban centers and allowing users to compare current trends with both five-year average prices, indicative of seasonal trends, and prices in the previous year. Sorghum, millet, and wheat are the most important food commodities in northern Sudan. Sorghum is the staple food for the majority of poor households in central and eastern Sudan regions while millet is the main staple food for majority of households in Darfur and some parts of Kordofan regions in western Sudan. Wheat most often used as a substitute all over northern Sudan but it is a staple food for northern states. Each of the markets represented here act as indicators for a broader region. Khartoum (Om Durman) is representative for Khartoum state, the main urban center of Sudan, and it has linkages with most of other markets in the country. El Obeid is the main assembly and wholesale market in North Kordofan and it is representative for the region, and it links market between central, western, and southern Sudan. El Fasher market is located in the capital of north Darfur state, a chronic food Source: FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges deficit area, and it is representative of the entire of Darfur FAMIS/FMoA, Sudan for the market data and region with links to Geneina market in the border with Chad information used to produce this report. -

SUDAN: West Darfur State UNHCR Presence and Refugee & IDP Locations

A A A SUDAN: West Darfur State UNHCR presence and refugee & IDP locations As of 18 Sep 2019 Ardamata #B A #BEl Riad Tandubayah BAbu Zar Sigiba El Geneina#C# #BAl Hujaj Girgira #BJammaa #BKrinding 1 & 2 Mastura\Sania WEST DARFUR #BKrinding 2 Dankud #B Kaidaba KULBUS Falankei Wadi Bardi village #B Kul#bus Abu Rumayl #B Bardani NORTH DARFUR Selea #B Istereina Aro Shorou Taziriba Hijeilija#B Gosmino #B Manjura A #B JEBEL MOON Ginfili Ngerma Djedid Abu Surug SIRBA #B Sirba Melmelli Armankul Abu Shajeira #B B # Bir Dagig Hamroh #B Kondobe #B Kuka WEST DARFUR A Kurgo CHAD Sultan house Birkat Tayr Kawm Dorti #B Abd Allah El RiadAro daBmata Abu #Zar A Jammaa B #B #Krinding 1 & 2 Al Hujaj #BC# #BBB Kaira Krinding 2## Derjeil El Geneina Kreinik EL GENEINA #B KREINIK A Geneina Goker #B DogoumSisi Nurei #B Misterei A #B A Kajilkajili Hagar Jembuh Murnei Kango Haraza Awita #B o #B A Ulang ZalingeiC# EGYPT SAUDI BEIDA Chero Kasi ARABIA LIBYA Zalingei Tabbi Nyebbei HABILA R Kortei e d S Red Sea e Arara a Beida town Northern Beida #B #B Arara AlwadiHabila Madares Nur Al Huda village River Nile #BBC# CHAD Al Salam# North A UNHCR office Darfur Khartoum Kassala Habila North ERITREA Kordofan Refugee Sites Futajiggi West El Gazira Darfur White Gedaref Sala + Lor CENTRAL DARFUR Nile POC IDP camp/sites Central West Sennar #B Darfur Kordofan Blue #B South Nile C# Refugee settlement South East Kordofan Darfur Darfur ETHIOPIA D Crossing point SOUTH SUDAN Main town Secondary town Seilo o Airfields FORO BARANGA SOUTH DARFUR Boundaries & Roads Mogara International boundary Foro Burunga State boundary #BC# Goldober Locality boundary Foro Baranga Primay road A Secondary road 5km The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

Information on the Internally Displaced Persons (Idps)

COI QUERY Country of Origin Sudan Main subject IDPs in Darfur and the Two Areas Question(s) Information on the internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Darfur and the Two Areas in the period of August 2019 - May 2020: - overview of numbers of IDPs and returnees: Darfur, The Two Areas, - living conditions and personal safety: Darfur, The Two Areas, - treatment by the Sovereign Council government: Darfur, The Two Areas. Date of completion 1 July 2020 Query Code Q15-2020 Contributing EU+ COI -- units (if applicable) Disclaimer This response to a COI query has been elaborated according to the EASO COI Report Methodology and EASO Writing and Referencing Guide. The information provided in this response has been researched, evaluated and processed with utmost care within a limited time frame. All sources used are referenced. A quality review has been performed in line with the above mentioned methodology. This document does not claim to be exhaustive neither conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to international protection. If a certain event, person or organisation is not mentioned in the report, this does not mean that the event has not taken place or that the person or organisation does not exist. Terminology used should not be regarded as indicative of a particular legal position. The information in the response does not necessarily reflect the opinion of EASO and makes no political statement whatsoever. The target audience is caseworkers, COI researchers, policy makers, and decision making authorities. The answer was finalised on 1 July 2020. Any event taking place after this date is not included in this answer. -

Darfur Destroyed Ethnic Cleansing by Government and Militia Forces in Western Sudan Summary

Human Rights Watch May 2004 Vol. 16, No. 6(A) DARFUR DESTROYED ETHNIC CLEANSING BY GOVERNMENT AND MILITIA FORCES IN WESTERN SUDAN SUMMARY.................................................................................................................................... 1 SUMMARY RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................................................... 3 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................... 5 ABUSES BY THE GOVERNMENT-JANJAWEED IN WEST DARFUR.................... 7 Mass Killings By the Government and Janjaweed............................................................... 8 Attacks and massacres in Dar Masalit ............................................................................... 8 Mass Executions of captured Fur men in Wadi Salih: 145 killed................................ 21 Other Mass Killings of Fur civilians in Wadi Salih........................................................ 23 Aerial bombardment of civilians ..........................................................................................24 Systematic Targeting of Marsali and Fur, Burnings of Marsalit Villages and Destruction of Food Stocks and Other Essential Items ..................................................26 Destruction of Mosques and Islamic Religious Articles............................................... 27 Killings and assault accompanying looting of property....................................................28 Rape and other forms -

COVID-19 Situation Overview & Response

SUDAN COVID-19 Situation Overview & Response 11 October 2020 CONFIRMED CASES by state NO. OF ACTIVITIES by Organization as of 11 October 2020 13,691 International boundary IOM 912 State boundary UNHCR 234 Confirmed cases Undetermined boundary Save the children 193 Abyei PCA Area Red Sea ECDO 150 385 UNFPA 135 Number of confirmed cases RIVER RED SEA 836 6,764 NILE Plan International Sudan 39 Welthungerhilfe (WHH) 34 Deaths Recovered 391 438 WHO 23 NORTHERN HOPE 22 HIGHLIGHTS 146 NCA 20 9,841 The Federal Ministry of Health identified the first case of COVID-19 on 12 March WVI 19 OXFAM 12 2020. United Nations organisations and their partners created a Corona Virus 228 NADA Alazhar 12 Country Preparedness and Response Plan (CPRP) to support the Government. EMERGENCY NGO Sudan 12 NORTH DARFUR KHARTOUM On 14 March 2020, the Government approved measures to prevent the spread of KASSALA EMERGENCY 12 Khartoum the virus which included reducing congestion in workplaces, closing schools 1,137 TGH 11 By Organization Type: NORTH KORDOFAN and banning large public gatherings. From 8 July 2020, the Government started AL GEZIRA World Vision Sudan 11 GEDAREF NORWEGIAN 9 174 7 WEST REFUGEE COUNCIL to ease the lock-down in Khartoum State. The nationwide curfew was changed 203 (9.33%) (0.38%) DARFUR WHITE 274 Italian Agency 7 from 6:00 pm to 5:00 am and bridges in the capital were re-opened. Travelling Development Co. NGO Governmental 34 NILE 243 Near East Foundation 7 between Khartoum and other states is still not allowed and airports will 191 SENNAR CAFOD 6 CENTRAL WEST gradually open pending further instructions from the Civil Aviation Authority. -

Sudan: Non Arab Darfuris

Country Policy and Information Note Sudan: Non Arab Darfuris Version 1.0 August 2017 Preface This note provides country of origin information (COI) and policy guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling particular types of protection and human rights claims. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the policy guidance contained with this note; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country information COI in this note has been researched in accordance with principles set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI) and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, namely taking into account its relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability. All information is carefully selected from generally reliable, publicly accessible sources or is information that can be made publicly available. Full publication details of supporting documentation are provided in footnotes. Multiple sourcing is normally used to ensure that the information is accurate, balanced and corroborated, and that a comprehensive and up-to-date picture at the time of publication is provided. Information is compared and contrasted, whenever possible, to provide a range of views and opinions. -

Trade and Market Bulletin • North Darfur

Trade and Market Bulletin North Darfur Darfur Development and Reconstruction Agency Covering the Quarter March to May 2012 • Vol. 2, No. 2 • www.dra-sudan.org • [email protected] Headlines • The upwards trend in cereal prices across North Darfur continued during this quarter, fuelled by inflation, the announcement of the removal of the fuel subsidy and seasonality of supply. • There has been some improvement in food security indicators in Malha, reflected in improved terms of trade between goats and cereals. This is partially attributable to the distribution of food aid by WFP and distribution of the strategic grain reserve stock by government. • The price of livestock has continued on an upwards trend in most markets in North Darfur. • The poor agricultural season and insecurity in the main cash crop production areas of North Darfur have caused prices to remain high in most monitored markets. There is poor availability of cash crops such as groundnuts and gum arabic in markets that would normally be well supplied. • In contrast, the price of tombac has steadily declined as conflict and trade restrictions in the traditional tombac-consuming markets of South Sudan, Blue Nile and South Kordofan states have negatively impacted the tombac economy in North Darfur. • High seasonal variation in the price of fresh fruit and vegetables continues to be recorded in North Darfur • Gold prospecting in more than seven sites in North Darfur has supported the livelihoods of some and triggered micro-economies • A number of major trade routes within North Darfur and connecting North Darfur with Khartoum and with South Darfur closed for periods during the quarter affecting trade flows and causing some commodity prices to rise. -

Peacew Rks [ Traditional Authorities’ Peacemaking Role in Darfur

TUBIANA, TANNER, AND ABDUL-JALIL TUBIANA, TANNER, [PEACEW RKS [ TRADITIONAL AUTHORITIES’ PEACEMAKING ROLE IN DARFUR TRADITIONAL AUTHORITIES’ PEACEMAKING ROLE IN DARFUR Jérôme Tubiana Victor Tanner Musa Adam Abdul-Jalil ABOUT THE REPORT The violence that has raged in Darfur for a decade is both a crisis of governance and a problem of law and order. As broader peace efforts have faltered, interest has increased in the capacity of local communities in Darfur to regulate conflict in their midst. All hope that traditional leaders, working within the framework of traditional justice, can be more successful in restoring some semblance of normalcy and security to Darfur. This report outlines the background to the conflict and the challenges in resolving it. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Victor Tanner has worked with war-affected populations in Africa, the Middle East, and the Balkans, both as an aid worker and a researcher, for more than twenty years. He first lived and worked in Darfur in 1988. Since 2002, he has conducted field research on local social and politi- cal dynamics in the Darfur conflict, visiting many parts of Darfur and eastern Chad as well. He speaks Sudanese Arabic. Jérôme Tubiana is an independent researcher specializing in Darfur, Sudan, and Chad, where he has worked as a consultant for various humanitarian organizations and research institutions, International The royal swords of the malik Ali Mohamedein Crisis Group, the Small Arms Survey, USIP, USAID, and of Am Boru, damaged by the Janjawid. AU-UN institutions. He is the author or coauthor of vari- ous articles, studies, and books, notably Chroniques du Darfour (2010). -

Food Security Status for the Household: a Case Study of Al

of Socia al lo rn m u ic o s J Bushara and Ibrahim, J Socialomics 2017, 6:4 Journal of Socialomics DOI: 10.1472/2167-0358.1000217 ISSN: 2167-0358 Case Study Open Access Food Security Status for the Household: A Case Study of Al-Qadarif State, Sudan (2016) Mohamed OA Bushara*and Ibrahim HH University of Gezira, WadMedani, Gezira State, Sudan *Corresponding author: Dr Mohamed OA Bushara. University of Gezira, WadMedani, Gezira State, Sudan, Tel: +249511826694; E-mail: [email protected] Rec date: April 20, 2017; Acc date: August 02, 2017; Pub date: August 15, 2017 Copyright: © 2017 Bushra MOA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Food security is under focused issue in Sudan and Al-Qadarif State is not apart from that. According to the integrated food security phases classification (IPC) report April 2015, about 60% of the population suffering from food insecurity in the state. This problem needs to be solved by a clear and sound policies and strategies. The main objective of this study is to evaluate the food security situation in the state, using a module concerning the demand side and to investigate and evaluate the Food Security and Nutrition (FSN) status in the state. To achieve this objective primary data were collected by the mean of questionnaires targeting house hold (394) sample size has been determined by using the Kerjcie and Morgan table, the household questionnaire was to determine the status of the food security within the state, using the USA.