Medial Prefrontal Cortex: Genes Linked to Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia Have Altered Expression in the Highly Social Maternal Phenotype

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

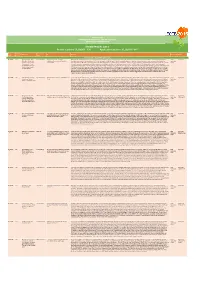

Relevant Sources for Orphan Disease Prevalence Data

16 December 2014 1 EMA/452415/2012 Rev. 1 Human Medicines Research and Development Support This document was valid from 16 December 2014 to 9 January 2018. It is no longer valid. Relevant sources for orphan disease prevalence data Sponsors applying for orphan designation for a medicine under Article 3(1) a paragraph 1 of Regulation (EC) No 141/2000 on orphan medicinal products are requested tovalid provide authoritative references to demonstrate that the condition, for which the medicine is intended, does not affect more than 5 in 10,000 people in the EU at the time the application is made. Possible sources include relevant scientific literature and databases. After more than 10 years of the implementation of the Orphan Regulation the Agency has accumulated a considerable amount of data on sources of prevalence of rare diseases from the applications for orphan designation. In most cases those sources are publicly available but not easily accessible. The Agency has decided to make the information collected so far publicly available. This will decrease the administrative burden for applicants for orphan designation and thus encourage the development of medicines for rare diseases. The information is provided in the table below will be updated regularly. The information provided herewith does not replace the obligation for the sponsor under the legislation to establish the prevalence (see Regulation (EC) No 141/2000 and the Guideline on the format and content of applications for designation as orphan medicinal product, ENTR/6283/00). Sponsors are still obliged to submit an original, up-to-date prevalence calculation supported by data with their orphan designation application. -

DATA Poster Numbers: P Da001 - 130 Application Posters: P Da001 - 041

POSTER LIST ORDERED ALPHABETICALLY BY POSTER TITLE GROUPED BY THEME/TRACK THEME/TRACK: DATA Poster numbers: P_Da001 - 130 Application posters: P_Da001 - 041 Poster EasyChair Presenting Author list Title Abstract Theme/track Topics number number author APPLICATION POSTERS WITHIN DATA THEME P_Da001 773 Benoît Carrères, Anne Benoît Carrères A systems approach to explore Microalgae are promising platforms for sustainable biofuel production. They produce triacyl-glycerides (TAG) which are easily converted into biofuel. When exposed to nitrogen limitation, Data/ Application Klok, Maria Suarez Diez, triacylglycerol production in Neochloris Neochloris oleoabundans accumulates up to 40% of its dry weight in TAG. However, a feasible production requires a decrease of production costs, which can be partially reached by Application Lenny de Jaeger, Mark oleoabundans increasing TAG yield.We built a constraint-based model describing primary metabolism of N. oleoabundans. It was grown in combinations of light absorption and nitrate supply rates and the poster Sturme, Packo Lamers, parameters needed for modeling of metabolism were measured. Fluxes were then calculated by flux balance analysis. cDNA samples of 16 experimental conditions were sequenced, Rene' Wijffels, Vitor Dos assembled and functionally annotated. Relative expression changes and relative flux changes for all reactions in the model were compared.The model predicts a maximum TAG yield on light Santos, Peter Schaap of 1.07g (mol photons)-1, more than 3 times current yield under optimal conditions. Furthermore, from optimization scenarios we concluded that increasing light efficiency has much higher and Dirk Martens potential to increase TAG yield than blocking entire pathways.Certain reaction expression patterns suggested an interdependence of the response to nitrogen and light supply. -

Genetic Determinants Underlying Rare Diseases Identified Using Next-Generation Sequencing Technologies

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-2-2018 1:30 PM Genetic determinants underlying rare diseases identified using next-generation sequencing technologies Rosettia Ho The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Hegele, Robert A. The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Biochemistry A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Science © Rosettia Ho 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Medical Genetics Commons Recommended Citation Ho, Rosettia, "Genetic determinants underlying rare diseases identified using next-generation sequencing technologies" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5497. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5497 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Rare disorders affect less than one in 2000 individuals, placing a huge burden on individuals, families and the health care system. Gene discovery is the starting point in understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying these diseases. The advent of next- generation sequencing has accelerated discovery of disease-causing genetic variants and is showing numerous benefits for research and medicine. I describe the application of next-generation sequencing, namely LipidSeq™ ‒ a targeted resequencing panel for the identification of dyslipidemia-associated variants ‒ and whole-exome sequencing, to identify genetic determinants of several rare diseases. Utilization of next-generation sequencing plus associated bioinformatics led to the discovery of disease-associated variants for 71 patients with lipodystrophy, two with early-onset obesity, and families with brachydactyly, cerebral atrophy, microcephaly-ichthyosis, and widow’s peak syndrome. -

The Epidemiology of Listeriosis in Pregnant

Jeffs et al. BMC Public Health (2020) 20:116 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8221-z RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The epidemiology of listeriosis in pregnant women and children in New Zealand from 1997 to 2016: an observational study Emma Jeffs1, Jonathan Williman2, Cheryl Brunton2, Joanna Gullam3 and Tony Walls1* Abstract Background: Listeria monocytogenes causes the foodborne infection listeriosis. Pregnant women, infants and immunocompromised children are at increased risk for infection. The aim of this study was to describe the trends in the epidemiology of disease notifications and hospital admissions due to listeriosis in pregnant women aged 15 to 45 years and children aged less than 15 years in New Zealand (NZ) from 1997 to 2016. Methods: In this population-based descriptive study, listeriosis notification and hospitalization rates from 1997 to 2016 were analyzed. Notification data were extracted from the Institute of Environmental Science and Research (ESR) Notifiable Diseases Database (EpiSurv) and hospitalization data were extracted from the National Minimum Dataset (NMDS). Pregnant women aged 15 to 45 years and children less than 15 years of age were included. Subgroup analysis was conducted for age and ethnicity. Outcomes of infection were described. Results: In the 20-year period considered, there were 147 pregnancy-associated cases of listeriosis either notified to ESR (n = 106) and/or coded in the NMDS (n = 99), giving a crude incidence rate of 12.3 (95% CI 10.4, 14.4) per 100, 000 births. In addition, there were 22 cases in children aged 28 days to < 15 years (incidence =0.12, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.19 per 100,000). -

Rainbows Basic Symptom Control in Paediatric Palliative Care

Ninth edition, 2013 Basic Symptom Control in Paediatric Palliative Care The Rainbows Children’s Hospice Guidelines www.togetherforshortlives.org.uk Basic Symptom Control in Paediatric Palliative Care The Rainbows Children’s Hospice Guidelines Ninth Edition, 2013 ISBN: 1 898447284 Basic Symptom Control in Paediatric Palliative Care © Dr Satbir Singh Jassal Formulary © The Association for Paediatric Palliative Medicine (APPM), March 2012 The formulary is due for revision at the end of 2014 Author: Dr Satbir Singh Jassal B.Med Sci, B.M., B.S., DRCOG, Dip Pall Med, DFSRH, MRCGP, FRCPCH (Hon), Medical Director Rainbows Children’s Hospice and General Practitioner Production: Myra Johnson and Katrina Kelly, Together for Short Lives Design: Qube Design Associates Ltd Certified by the Information Standard Together for Short Lives is the leading UK charity that speaks for all children with life-threatening and life-limiting conditions and all those who support, love and care for them. When children are unlikely to reach adulthood, we aim to make a lifetime of difference for them and their families. Together for Short Lives 4th Floor, 48-52 Bridge House, Baldwin Street, Bristol BS1 1QB T: 0117 989 7820 [email protected] www.togetherforshortlives.org.uk Together for Short Lives is a registered charity in England and Wales (1144022) and Scotland (SC044139) and a company limited by guarantee (7783702) Disclaimer: Although Together for Short Lives has taken care to ensure that the contents of this document are correct and up to date at the time of publishing, the information contained in the document is intended for general use only. -

Neuropathy in Childhood Mitochondrial Disease, Including Riboflavin Transporter Deficiency: Phenotype, Neurophysiology and Disease-Modifying Therapy in a Recently Described Treatable

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Copyright Service. sydney.edu.au/copyright Neuropathy in childhood mitochondrial disease, including riboflavin transporter deficiency: phenotype, neurophysiology and disease-modifying therapy in a recently described treatable disorder Dr Manoj Peter Menezes A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the faculty of Medicine, The University of Sydney, 2015. Submitted October 2015 1 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person or material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of the university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. -

Machine Learning Based Psychological Disease Support Model Assisting Psychoanalysts and Individuals in Clinical Decision Ministration

International Journal of Computing and Digital Systems ISSN (2210-142X) Int. J. Com. Dig. Sys. 9, No.4 (July-2020) http://dx.doi.org/10.12785/ijcds/090414 Machine Learning Based Psychological Disease Support Model Assisting Psychoanalysts and Individuals in Clinical Decision Ministration Vikas Kamra1, Praveen Kumar2 and Masoud Mohammadian3 1Research Scholar, Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Noida, India 2CSE Department, Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Noida, India 3Faculty of Science and Technology, University of Canberra, Australia Received 11 Oct.2019, Revised 9 Mar. 2020, Accepted 11 May 2020, Published 1 Jul. 2020 Abstract: Mental Pressure is a significant contributor to an individual's health and is directly linked with various diseases including depression and mental disorder. It is therefore extremely important to monitor the patient's misbehavior. Therapeutic-psychology based on machine learning algorithms clearly concentrates on studying multifaceted datasets to deduce statistical features in order to create generalized projections about patients. A novel paradigm to develop Psychological Disease Support Model (PDSM) will be discussed through this research paper. This model will support diagnosis of various psychological diseases like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder. It will take some health parameters as input from end user, process that data based on machine learning approach and provides desired outcome in user friendly way. Existing methods of wellness surveillance continue to confront many difficulties owing to inadequate information from healthcare records. The proposed approach seeks to develop a scheme of autonomous choice assistance for an initial treatment of important psychological occurrences. Machine based learning is widely described as a methodology that automatically knows how to solve the issue optimally, instead of being programmed by natural beings in order to provide a set answer. -

Orphanet Report Series Rare Diseases Collection

Orphanet Report Series Rare Diseases collection January 2013 Disease Registries in Europe www.orpha.net 20102206 Table of contents Methodology 3 List of rare diseases that are covered by the listed registries 4 Summary 13 1- Distribution of registries by country 13 2- Distribution of registries by coverage 14 3- Distribution of registries by affiliation 14 Distribution of registries by country 15 European registries 38 International registries 41 Orphanet Report Series - Disease Registries in Europe - January 2013 2 http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/cahiers/docs/GB/Registries.pdf Methodology Patient registries and databases constitute key instruments to develop clinical research in the field of rare diseases (RD), to improve patient care and healthcare planning. They are the only way to pool data in order to achieve a sufficient sample size for epidemiological and/or clinical research. They are vital to assess the feasibility of clinical trials, to facilitate the planning of appropriate clinical trials and to support the enrolment of patients. Registries of patients treated with orphan drugs are particularly relevant as they allow the gathering of evidence on the effectiveness of the treatment and on its possible side effects, keeping in mind that marketing authorisation is usually granted at a time when evidence is still limited although already somewhat convincing. This report gather the information collected by Orphanet so far, regarding systematic collections of data for a specific disease or a group of diseases. Cancer registries are listed only if they belong to the network RARECARE or focus on a rare form of cancer. The report includes data about EU countries and surrounding countries participating to the Orphanet consortium. -

A Machine Learning Approach: Using Predictive Analytics to Identify and Analyze High Risks Patients with Heart Disease

International Journal of Machine Learning and Computing, Vol. 9, No. 6, December 2019 A Machine Learning Approach: Using Predictive Analytics to Identify and Analyze High Risks Patients with Heart Disease Fadoua Khennou, Charif Fahim, Habiba Chaoui, and Nour El Houda Chaoui rapidly towards the analysis of electronic health record Abstract—The risk of developing early heart disease is always systems [2]. This actually lead to the generation of prominent. In fact, according to the Central of Disease Control voluminous health-related data that can be an important asset and Prevention (CDC), Cardiovascular disease accounts for in improving the overall quality of health care and the nearly 801,000 deaths in the US. well-being of people, if used wisely. In this paper, we present a machine learning and decision based system for heart disease prediction. The goal of this current work is to propose an approach to We validate our approach on the Heart Disease Dataset improve heart disease prediction using machine learning and gathered from the UCI machine learning repository. data mining techniques. Cleveland, Hungarian and Switzerland datasets are Cardio-vascular diseases relate to the heart and vessels. combined and trained with the use of SVM and Naïve Bayes They represent today in our society the main cause of deaths algorithms. before cancers and road accidents [3]. Comparison and analysis with other models show that the This refers to conditions that involve a disorder of the accuracy of the proposed approach is 87% and 86% for SVM irrigation of the heart by the coronary arteries. They can take and Naïve Bayes respectively, which is much higher comparing to the existing approaches that use a small subset of data and no different forms: angina pectoris or angina, heart failure, imputation technique. -

Appendix 1 Top Ten Favourite Web Sites

Appendix 1 Top Ten Favourite Web Sites 1. Food and Nutrition Information Center "'" Netscape - [Food and Nutllhon Infolmdhon Center, 8(!iJ E'j localion: hltp"lIwww.nalusdagovlfnrc/ .About the Food and Nutrition Information Center • Food and Nutrition Information Center Publications and Databases Software I WlC-Developed Matenals I Nutri-Topics I Nutntlon Education and Tralmng (NET) Program Products I and much more • USDA/FDA Foodborne Illness Education Information Center • Healthy School Meals Resource System • USDA Food and Nutrition Information Dietary Guidelines for Americans I Food Composlbon Data I Third Repo rt on Nutrition Momtonng I Food & Nutrition Research Briefs I Food GUide Pyramid I and much more • Index of Food and Nutrition Internet Resources • Document Done 70 The Internet for Nurses and Allied Health Professionals 2. GoldenAge Net ' .... Nelle.pe j'Neleome To GoldenAge Nell IIII~~ loeaho.. : Iitp.lleiomeciostv...... edulgoIdenaoeImo lim Welcome to .!.l GOldenAge.Net GoldenAge. Net (formerly known as AGE NET) has been recognized by USA TODAy' and Contemporary Long TemJ Care Magazine as a great starting point. for Internet. research on. "aging" topiCS. oOJment Done lid 1 ,1..; Nchcdpe (Welcome 10 GoldcnAqe Nel T able of Conh:nhl I!I~ EJ • LONG TERM CARE ADMINISTRATION and ASSISTED LIVING proVides resources for semor clDzens. students. and professionals that work in semor care centers • CommerCial Related Sites Include online magazines, services, and products that target the elderly and their caregivers • Govemmental Sites -

Dysregulation of Circrna Expression in the Peripheral Blood of Individuals with Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder

Dysregulation of circRNA Expression in the Peripheral Blood of Individuals With Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder Ebrahim Mahmoudi The University of Newcastle Melissa J. Green UNSW: University of New South Wales Murray Cairns ( [email protected] ) The University of Newcastle https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2490-2538 Research Article Keywords: circRNA, PBMCs, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, differential expression Posted Date: February 16th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-231116/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published at Journal of Molecular Medicine on March 29th, 2021. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00109-021-02070-6. Page 1/21 Abstract Circular RNA (circRNA) are head-to-tail back-spliced RNA transcripts that have been linked to several biological processes and their perturbation is evident in human diseases, including neurological disorders. There is also emerging research suggesting circRNA expression may also be altered in psychiatric and behavioural syndromes. Here, we provide a comprehensive analysis of circRNA expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 39 patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder as well as 20 healthy individuals using deep RNA-seq. We observed systematic alternative splicing leading to a complex and diverse prole of RNA transcripts including 8,762 high condence circRNAs. More specic scrutiny of the circular transcriptome in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, compared to a non-psychiatric control group, revealed signicant dysregulation of 55 circRNAs with a bias towards downregulation. These molecules were predicted to interact with a large number of miRNAs that target genes enriched in psychiatric disorders. -

Semantic Prioritization of Novel Causative Genomic Variants in Mendelian and Oligogenic Diseases

Semantic Prioritization of Novel Causative Genomic Variants in Mendelian and Oligogenic Diseases Dissertation by Imane Boudellioua In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy King Abdullah University of Science and Technology Thuwal, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia February, 2019 2 EXAMINATION COMMITTEE PAGE The dissertation of Imane Boudellioua is approved by the examination committee Committee Chairperson: Prof. Robert Hoehndorf Committee Members: Prof. Stefan T. Arold, Prof. Xin Gao, and Prof. Dietrich Rebholz-Schuhmann 3 ©February, 2019 Imane Boudellioua All Rights Reserved 4 ABSTRACT Semantic Prioritization of Novel Causative Genomic Variants in Mendelian and Oligogenic Diseases Imane Boudellioua Recent advances in Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies have facili- tated the generation of massive amounts of genomic data which in turn is bringing the promise that personalized medicine will soon become widely available. As a result, there is an increasing pressure to develop computational tools to analyze and interpret genomic data. In this dissertation, we present a systematic approach for interrogat- ing patients' genomes to identify candidate causal genomic variants of Mendelian and oligogenic diseases. To achieve that, we leverage the use of biomedical data available from extensive biological experiments along with machine learning techniques to build predictive models that rival the currently adopted approaches in the field. We inte- grate a collection of features representing molecular information about the genomic variants and information derived from biological networks. Furthermore, we incorpo- rate genotype-phenotype relations by exploiting semantic technologies and automated reasoning inferred throughout a cross-species phenotypic ontology network obtained from human, mouse, and zebra fish studies.