Rainbows Basic Symptom Control in Paediatric Palliative Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relevant Sources for Orphan Disease Prevalence Data

16 December 2014 1 EMA/452415/2012 Rev. 1 Human Medicines Research and Development Support This document was valid from 16 December 2014 to 9 January 2018. It is no longer valid. Relevant sources for orphan disease prevalence data Sponsors applying for orphan designation for a medicine under Article 3(1) a paragraph 1 of Regulation (EC) No 141/2000 on orphan medicinal products are requested tovalid provide authoritative references to demonstrate that the condition, for which the medicine is intended, does not affect more than 5 in 10,000 people in the EU at the time the application is made. Possible sources include relevant scientific literature and databases. After more than 10 years of the implementation of the Orphan Regulation the Agency has accumulated a considerable amount of data on sources of prevalence of rare diseases from the applications for orphan designation. In most cases those sources are publicly available but not easily accessible. The Agency has decided to make the information collected so far publicly available. This will decrease the administrative burden for applicants for orphan designation and thus encourage the development of medicines for rare diseases. The information is provided in the table below will be updated regularly. The information provided herewith does not replace the obligation for the sponsor under the legislation to establish the prevalence (see Regulation (EC) No 141/2000 and the Guideline on the format and content of applications for designation as orphan medicinal product, ENTR/6283/00). Sponsors are still obliged to submit an original, up-to-date prevalence calculation supported by data with their orphan designation application. -

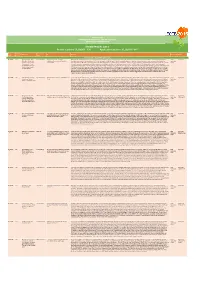

DATA Poster Numbers: P Da001 - 130 Application Posters: P Da001 - 041

POSTER LIST ORDERED ALPHABETICALLY BY POSTER TITLE GROUPED BY THEME/TRACK THEME/TRACK: DATA Poster numbers: P_Da001 - 130 Application posters: P_Da001 - 041 Poster EasyChair Presenting Author list Title Abstract Theme/track Topics number number author APPLICATION POSTERS WITHIN DATA THEME P_Da001 773 Benoît Carrères, Anne Benoît Carrères A systems approach to explore Microalgae are promising platforms for sustainable biofuel production. They produce triacyl-glycerides (TAG) which are easily converted into biofuel. When exposed to nitrogen limitation, Data/ Application Klok, Maria Suarez Diez, triacylglycerol production in Neochloris Neochloris oleoabundans accumulates up to 40% of its dry weight in TAG. However, a feasible production requires a decrease of production costs, which can be partially reached by Application Lenny de Jaeger, Mark oleoabundans increasing TAG yield.We built a constraint-based model describing primary metabolism of N. oleoabundans. It was grown in combinations of light absorption and nitrate supply rates and the poster Sturme, Packo Lamers, parameters needed for modeling of metabolism were measured. Fluxes were then calculated by flux balance analysis. cDNA samples of 16 experimental conditions were sequenced, Rene' Wijffels, Vitor Dos assembled and functionally annotated. Relative expression changes and relative flux changes for all reactions in the model were compared.The model predicts a maximum TAG yield on light Santos, Peter Schaap of 1.07g (mol photons)-1, more than 3 times current yield under optimal conditions. Furthermore, from optimization scenarios we concluded that increasing light efficiency has much higher and Dirk Martens potential to increase TAG yield than blocking entire pathways.Certain reaction expression patterns suggested an interdependence of the response to nitrogen and light supply. -

Genetic Determinants Underlying Rare Diseases Identified Using Next-Generation Sequencing Technologies

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-2-2018 1:30 PM Genetic determinants underlying rare diseases identified using next-generation sequencing technologies Rosettia Ho The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Hegele, Robert A. The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Biochemistry A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Science © Rosettia Ho 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Medical Genetics Commons Recommended Citation Ho, Rosettia, "Genetic determinants underlying rare diseases identified using next-generation sequencing technologies" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5497. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5497 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Rare disorders affect less than one in 2000 individuals, placing a huge burden on individuals, families and the health care system. Gene discovery is the starting point in understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying these diseases. The advent of next- generation sequencing has accelerated discovery of disease-causing genetic variants and is showing numerous benefits for research and medicine. I describe the application of next-generation sequencing, namely LipidSeq™ ‒ a targeted resequencing panel for the identification of dyslipidemia-associated variants ‒ and whole-exome sequencing, to identify genetic determinants of several rare diseases. Utilization of next-generation sequencing plus associated bioinformatics led to the discovery of disease-associated variants for 71 patients with lipodystrophy, two with early-onset obesity, and families with brachydactyly, cerebral atrophy, microcephaly-ichthyosis, and widow’s peak syndrome. -

Elearn Comfort Promise

and treat pain Reducing pain with needle procedures Our Objective Design, test & deploy the clinical practices, and foster the culture, required to eliminate all needless pain and to minimize all moderate and severe physical pain and distress…………… Goal: To partner with patients and families to create a better patient experience. Scope: All acute and procedural pain Initial efforts : We started with needle procedures, because the majority of patients and families named them as their (child’s)worst pain. This will include: Lab draws ,POC testing, injections, PIV starts, PICC placements, arterial sticks or line placements, and PAC access. 2 | © 2013 Needle Procedures Current staff attitudes: •Needles don’t hurt that much, especially finger sticks. • The pain of a needle stick is unavoidable… •“So just get it the first time and do it quick!” Current reality: •Needle sticks do hurt and cause anxiety(most kids rate them 6/10). •Finger and heel sticks are usually more painful, take longer, and may require more than 1 stick. •We have solid evidence on how to reduce or eliminate needle pain. 3 | © 2013 Why do we care? • Most children receive a minimum of 18 needle procedures, in their first year of life. • If they were born pre-term the exposure is significantly higher; − Critically ill infant may experience >480 painful procedures during NICU stay. − Neonates at 33 weeks gestational age admitted to NICU experienced an average of 10 painful procedures/day; 79 %were performed without any type of analgesia. Barker DP (1995) Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 72:F47-8; Johnston CC (1997) Clin J Pain 13:308-12 Carbajal, R., Rousset, A.,Danan, C., Coquery, S., Nolent, P., Ducrocq, S., et al. -

The Epidemiology of Listeriosis in Pregnant

Jeffs et al. BMC Public Health (2020) 20:116 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8221-z RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access The epidemiology of listeriosis in pregnant women and children in New Zealand from 1997 to 2016: an observational study Emma Jeffs1, Jonathan Williman2, Cheryl Brunton2, Joanna Gullam3 and Tony Walls1* Abstract Background: Listeria monocytogenes causes the foodborne infection listeriosis. Pregnant women, infants and immunocompromised children are at increased risk for infection. The aim of this study was to describe the trends in the epidemiology of disease notifications and hospital admissions due to listeriosis in pregnant women aged 15 to 45 years and children aged less than 15 years in New Zealand (NZ) from 1997 to 2016. Methods: In this population-based descriptive study, listeriosis notification and hospitalization rates from 1997 to 2016 were analyzed. Notification data were extracted from the Institute of Environmental Science and Research (ESR) Notifiable Diseases Database (EpiSurv) and hospitalization data were extracted from the National Minimum Dataset (NMDS). Pregnant women aged 15 to 45 years and children less than 15 years of age were included. Subgroup analysis was conducted for age and ethnicity. Outcomes of infection were described. Results: In the 20-year period considered, there were 147 pregnancy-associated cases of listeriosis either notified to ESR (n = 106) and/or coded in the NMDS (n = 99), giving a crude incidence rate of 12.3 (95% CI 10.4, 14.4) per 100, 000 births. In addition, there were 22 cases in children aged 28 days to < 15 years (incidence =0.12, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.19 per 100,000). -

Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Friday, April 29, 2005 Part II Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 42 CFR Part 418 Medicare Program; Proposed Hospice Wage Index for Fiscal Year 2006; Proposed Rule VerDate jul<14>2003 16:52 Apr 28, 2005 Jkt 205001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\29APP2.SGM 29APP2 22394 Federal Register / Vol. 70, No. 82 / Friday, April 29, 2005 / Proposed Rules DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND (Because access to the interior of the impending death of an individual HUMAN SERVICES HHH Building is not readily available to warrants a change in the focus from persons without Federal Government curative care to palliative care for relief Centers for Medicare & Medicaid identification, commenters are of pain and for symptom management. Services encouraged to leave their comments in The goal of hospice care is to help the CMS drop slots located in the main terminally ill individuals continue life 42 CFR Part 418 lobby of the building. A stamp-in clock with minimal disruption to normal [CMS–1286–P] is available for persons wishing to retain activities while remaining primarily in a proof of filing by stamping in and the home environment. A hospice uses RIN 0938–AN89 retaining an extra copy of the comments an interdisciplinary approach to deliver being filed.) medical, social, psychological, Medicare Program; Proposed Hospice Comments mailed to the addresses emotional, and spiritual services Wage Index for Fiscal Year 2006 indicated as appropriate for hand or through use of a broad spectrum of AGENCY: Centers for Medicare & courier delivery may be delayed and professional and other caregivers, with Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. -

Psychological Trauma (PTPPPA 2015): Prenatal, Perinatal

SERBIAN GOVERNMENT MINISTRY OF EDUCATION, SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT PROCEEDINGS 1st International Congress on Psychological Trauma: Prenatal, Perinatal & Postnatal Aspects (PTPPPA 2015) Editors Grigori Brekhman Mirjana Sovilj Dejan Raković Belgrade, Crowne Plaza 15-16 May, 2015 Patrons: Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development – Republic of Serbia Association for Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology and Health – USA Cosmoanelixis, Prenatal & Life Sciences - Greece DRF Fund for Promoting Holistic Research and Ecology of Consciousness - Serbia Organizers: Life activities advancement center - Serbia The Institute for Experimental Phonetics and Speech Pathology - Serbia The International Society of Pre- and Perinatal Psychology and Medicine - Germany Organiziation: Organizing Committee, IEPSP, LAAC Secretariat, Gospodar Jovanova 35, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia. Tel./Fax: (+381 11 3208 544, +381 11 2624 168) e-mail: [email protected] web: http://www.iefpg.org.rs Publisher: Life activities advancement center The Institute for Experimental Phonetics and Speech Pathology Electronic version on publication Editors: Grigori Brekhman, Mirjana Sovilj, Dejan Raković Circulation: 500 ISBN: 978-86-89431-05-6 2 Scientific Committee Organizing Committee Chair: Chairs: G. Brekhman (Israel) S. Maksimović (Serbia) V. Kljajević (Serbia) Vice-chairs: M. Sovilj (Serbia) Members: D. Raković (Serbia) T. Adamović(Serbia) S. Arandjelović (Serbia) Lj. Jeličić (Serbia) Members: V. Ilić (Serbia) E. Ailamazjan (Russia) S. Janković-Ražnatović (Serbia) S. Bardsley (USA) J. Jovanović (Serbia) H. Blazy (Germany) M. Mićović (Serbia) P. Fedor-Freybergh (Slovakia) Ž. Mihajlović (Serbia) M. Dunjić (Serbia) D. Pavlović (Serbia) D. Djordjević (Serbia) L. Trifunović (Serbia) O. Gouni (Greece) O. Vulićević (Serbia) Č. Hadži Nikolić (Serbia) M. Vujović (Serbia) S. Hildebrandt (Germany) S. Janjatovic (Italy) L. -

Neuropathy in Childhood Mitochondrial Disease, Including Riboflavin Transporter Deficiency: Phenotype, Neurophysiology and Disease-Modifying Therapy in a Recently Described Treatable

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Copyright Service. sydney.edu.au/copyright Neuropathy in childhood mitochondrial disease, including riboflavin transporter deficiency: phenotype, neurophysiology and disease-modifying therapy in a recently described treatable disorder Dr Manoj Peter Menezes A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the faculty of Medicine, The University of Sydney, 2015. Submitted October 2015 1 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person or material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of the university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. -

Machine Learning Based Psychological Disease Support Model Assisting Psychoanalysts and Individuals in Clinical Decision Ministration

International Journal of Computing and Digital Systems ISSN (2210-142X) Int. J. Com. Dig. Sys. 9, No.4 (July-2020) http://dx.doi.org/10.12785/ijcds/090414 Machine Learning Based Psychological Disease Support Model Assisting Psychoanalysts and Individuals in Clinical Decision Ministration Vikas Kamra1, Praveen Kumar2 and Masoud Mohammadian3 1Research Scholar, Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Noida, India 2CSE Department, Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Noida, India 3Faculty of Science and Technology, University of Canberra, Australia Received 11 Oct.2019, Revised 9 Mar. 2020, Accepted 11 May 2020, Published 1 Jul. 2020 Abstract: Mental Pressure is a significant contributor to an individual's health and is directly linked with various diseases including depression and mental disorder. It is therefore extremely important to monitor the patient's misbehavior. Therapeutic-psychology based on machine learning algorithms clearly concentrates on studying multifaceted datasets to deduce statistical features in order to create generalized projections about patients. A novel paradigm to develop Psychological Disease Support Model (PDSM) will be discussed through this research paper. This model will support diagnosis of various psychological diseases like schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder. It will take some health parameters as input from end user, process that data based on machine learning approach and provides desired outcome in user friendly way. Existing methods of wellness surveillance continue to confront many difficulties owing to inadequate information from healthcare records. The proposed approach seeks to develop a scheme of autonomous choice assistance for an initial treatment of important psychological occurrences. Machine based learning is widely described as a methodology that automatically knows how to solve the issue optimally, instead of being programmed by natural beings in order to provide a set answer. -

Orphanet Report Series Rare Diseases Collection

Orphanet Report Series Rare Diseases collection January 2013 Disease Registries in Europe www.orpha.net 20102206 Table of contents Methodology 3 List of rare diseases that are covered by the listed registries 4 Summary 13 1- Distribution of registries by country 13 2- Distribution of registries by coverage 14 3- Distribution of registries by affiliation 14 Distribution of registries by country 15 European registries 38 International registries 41 Orphanet Report Series - Disease Registries in Europe - January 2013 2 http://www.orpha.net/orphacom/cahiers/docs/GB/Registries.pdf Methodology Patient registries and databases constitute key instruments to develop clinical research in the field of rare diseases (RD), to improve patient care and healthcare planning. They are the only way to pool data in order to achieve a sufficient sample size for epidemiological and/or clinical research. They are vital to assess the feasibility of clinical trials, to facilitate the planning of appropriate clinical trials and to support the enrolment of patients. Registries of patients treated with orphan drugs are particularly relevant as they allow the gathering of evidence on the effectiveness of the treatment and on its possible side effects, keeping in mind that marketing authorisation is usually granted at a time when evidence is still limited although already somewhat convincing. This report gather the information collected by Orphanet so far, regarding systematic collections of data for a specific disease or a group of diseases. Cancer registries are listed only if they belong to the network RARECARE or focus on a rare form of cancer. The report includes data about EU countries and surrounding countries participating to the Orphanet consortium. -

Suffering and Science

1 Special Interest Group for Philosophy and Ethics Suffering and Science Launde Abbey 23 - 26 June 2008 1 Contents Introduction Peter Wemyss-Gorman 3 Science and Suffering 1. Suffering, mind and the brain: Neuroimaging of religion-based coping 4 Katja Wiech 2. Can we ‗Face‘ the pain? Levinasian phenomenology and pain 11 Alex Cahana 3. Why pain? A psychological and evolutionary perspective 19 Amanda Williams 4. Consciousness studies and understanding pain: Reciprocal lessons 25 Ron Chrisley 5. Suffering: Is it just matter and its transformations or are we missing 34 something? Alan Lannigan _ 6. Mind-Body dualism and Pain 43 Barbara Duncan 7. Placebos and the relief of pain and suffering 55 Paul Dieppe 8. Cultural issues and pain 60 Sue Peacock 9. Professionalism and managerialism in Lord Darzi‘s NHS 66 Michael Platt 10. Nice ‗n nasty; interestin‘ and mundane – Fairness in the clinic 69 Willy Notcutt 10. Poetry and Pain 74 Michael Hare Duke For further information or to obtain copies of this report or the transcript of the 2007 meeting on Suffering and the World's Religions, contact Peter Wemyss-Gorman. Email: [email protected] The Special Interest Group is grateful to NAPP Pharmaceuticals for their generous support of this meeting. Illustration of the front cover used by kind permission of Launde Abbey 2 Contributors Katja Wiech: Post-doctoral Fellow in the Oxford Centre for Functional MRI of the Brain Alex Cahana: Professor and Chair, John Bonica Pain Division, Seattle Amanda Williams: Clinical Psychologist, St Thomas‘ -

Pain Education Manual for Physical Therapist Professional Degree Programs

Pain Education Manual For Physical Therapist Professional Degree Programs Authors: Mark Shepherd, PT, DPT, OCS, FAAOMPT Bellin College, Green Bay, WI Carol Courtney, PT, PhD, ATC Northwestern University, Chicago, IL Craig Wassinger, PT, PhD East Tennessee State University, Johnson City, TN D. Scott Davis, PT, MS, EdD, OCS Marshall University, Huntington, WV Bill Rubine, MS, PT Oregon Health and Science University Healthcare, Portland, OR Reviewers: Kathleen Sluka, PT, PhD Marie Bement, PT, MPT, PhD Kory Zimney, PT, DPT, PhD Shana Harrington, PT, PhD Rachel Tran, PT, DPT, NCS Megan Sions, PT, PhD, DPT, OCS Kim Clarno, PT, DPT, OCS Jon Weiss, PT, DPT, GCS Amethyst Messer, PT, DPT, GCS Copyright 2021, Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy, APTA, Inc. Introduction The presence of pain is one of the most common reasons people seek health care services. National surveys have found that persistent pain—defined as pain lasting longer than 3 months—affects approximately 100 million American adults, roughly one-third of the United States (US) population, and that the economic costs attributable to such pain approach $600 billion annually.1 With the prevalence of individuals seeking relief from pain, the rise of the opioid crisis came front and center in the United States. In 2021, The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) updated a published white paper detailing the role physical therapists (PT) have in the treatment of pain and ultimately, the opioid crisis.2 The white paper explicitly states, “Physical therapists, who engage in an examination process that focuses on not only the symptoms of pain but also the movement patterns that may be contributing to pain, must become central to this multidisciplinary strategy.”2(p5) Physical therapists must work collaboratively with patients, health care providers, payers, and legislators to help stop the opioid crisis, but with this call to arms, there is a need for evidence informed knowledge and skills to appropriately address those in pain.