The Bustling Alexander

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives

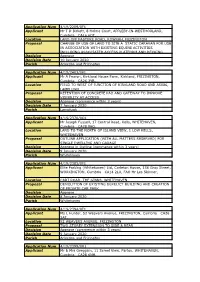

Cumbria Archive Service CATALOGUE: new additions August 2021 Carlisle Archive Centre The list below comprises additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives from 1 January - 31 July 2021. Ref_No Title Description Date BRA British Records Association Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Moor, yeoman to Ranald Whitfield the son and heir of John Conveyance of messuage and Whitfield of Standerholm, Alston BRA/1/2/1 tenement at Clargill, Alston 7 Feb 1579 Moor, gent. Consideration £21 for Moor a messuage and tenement at Clargill currently in the holding of Thomas Archer Thomas Archer of Alston Moor, yeoman to Nicholas Whitfield of Clargill, Alston Moor, consideration £36 13s 4d for a 20 June BRA/1/2/2 Conveyance of a lease messuage and tenement at 1580 Clargill, rent 10s, which Thomas Archer lately had of the grant of Cuthbert Baynbrigg by a deed dated 22 May 1556 Ranold Whitfield son and heir of John Whitfield of Ranaldholme, Cumberland to William Moore of Heshewell, Northumberland, yeoman. Recites obligation Conveyance of messuage and between John Whitfield and one 16 June BRA/1/2/3 tenement at Clargill, customary William Whitfield of the City of 1587 rent 10s Durham, draper unto the said William Moore dated 13 Feb 1579 for his messuage and tenement, yearly rent 10s at Clargill late in the occupation of Nicholas Whitfield Thomas Moore of Clargill, Alston Moor, yeoman to Thomas Stevenson and John Stevenson of Corby Gates, yeoman. Recites Feb 1578 Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Conveyance of messuage and BRA/1/2/4 Moor, yeoman bargained and sold 1 Jun 1616 tenement at Clargill to Raynold Whitfield son of John Whitfield of Randelholme, gent. -

Copeland Unclassified Roads - Published January 2021

Copeland Unclassified Roads - Published January 2021 • The list has been prepared using the available information from records compiled by the County Council and is correct to the best of our knowledge. It does not, however, constitute a definitive statement as to the status of any particular highway. • This is not a comprehensive list of the entire highway network in Cumbria although the majority of streets are included for information purposes. • The extent of the highway maintainable at public expense is not available on the list and can only be determined through the search process. • The List of Streets is a live record and is constantly being amended and updated. We update and republish it every 3 months. • Like many rural authorities, where some highways have no name at all, we usually record our information using a road numbering reference system. Street descriptors will be added to the list during the updating process along with any other missing information. • The list does not contain Recorded Public Rights of Way as shown on Cumbria County Council’s 1976 Definitive Map, nor does it contain streets that are privately maintained. • The list is property of Cumbria County Council and is only available to the public for viewing purposes and must not be copied or distributed. -

Application Num 4/19/2209/0F1 Applicant Mr T D Birkett, 8 Holme

Application Num 4/19/2209/0F1 Applicant Mr T D Birkett, 8 Holme Court, APPLEBY-IN-WESTMORLAND, Cumbria CA16 6QT, Location LAND OFF PASTURE ROAD, ROWRAH, FRIZINGTON Proposal CHANGE OF USE OF LAND TO SITE A STATIC CARAVAN FOR USE IN ASSOCIATION WITH EXISTING EQUINE ACTIVITIES INCLUDING ASSOCIATED ACCESS PLATFORM AND DECKING Decision Approve Decision Date 10 January 2020 Parish Arlecdon and Frizington Application Num 4/19/2403/0F1 Applicant Mr A Fearon, Kirkland House Farm, Kirkland, FRIZINGTON, Cumbria CA26 3YB, Location FIELD TO WEST OF JUNCTION OF KIRKLAND ROAD AND A5086, LAMPLUGH Proposal RETENTION OF CONCRETE PAD AND GATEWAY TO IMPROVE VISIBILITY AT ACCESS Decision Approve (commence within 3 years) Decision Date 7 January 2020 Parish Lamplugh Application Num 4/19/2370/0O1 Applicant Mr Joseph Fussell, 17 Central Road, Kells, WHITEHAVEN, Cumbria CA28 9EQ, Location LAND TO THE NORTH OF ISLAND VIEW, 1 LOW KELLS, WHITEHAVEN Proposal OUTLINE APPLICATION (WITH ALL MATTERS RESERVED) FOR SINGLE DWELLING AND GARAGE Decision Approve in Outline (commence within 3 years) Decision Date 9 January 2020 Parish Whitehaven Application Num 4/19/2383/0F1 Applicant Elite Parking (Whitehaven) Ltd, Carleton House, 136 Gray Street, WORKINGTON, Cumbria CA14 2LU, FAO Mr Les Skinner, Location CART ROAD, THE GINNS, WHITEHAVEN Proposal DEMOLITION OF EXISTING DERELICT BUILDING AND CREATION OF PRIVATE CAR PARK Decision Approve Decision Date 8 January 2020 Parish Whitehaven Application Num 4/19/2394/0F1 Applicant Ms L Hunter, 52 Weavers Avenue, FRIZINGTON, Cumbria CA26 -

Cumbrian Railway Ancestors D Surnames Surname First Names

Cumbrian Railway Ancestors D surnames Year Age Surname First names Employment Location Company Date Notes entered entered Source service service WW1 service, 4th Kings Own (Royal Dacre F. Supt of Line's Dept FR FUR 1914-18 0 FR Roll of Honour Lancaster) Regt., Private Dacre Frank Clerk Cark & Cartmel FUR 00/05/1911 AMB Dacre R. Yardman Cleator Moor Goods JTL 25/06/1892 Wage 24/- pw. Resigned JtL minute Nov 92 Dacre Richard Porter Cark & Cartmel FUR 27/12/1869 Entered servive on 18/- 20/- Mar 1872 1869 22 FR Staff Index 1845-1873 Fined 2/6 for being worse for drink and Dacre Richard Porter Cark & Cartmel FUR 00/01/1872 1869 22 FR Staff Index 1845-1873 leaving lamps burning Dacre Richard Porter Cark & Cartmel FUR 00/06/1872 Discharged for fighting Jun 1872 1869 22 FR Staff Index 1845-1873 Dacre Richard Temporary Porter Cark & Cartmel FUR 01/03/1875 Entered service. Discharged May 1875 1875 26 FR Staff Register Dacre Richard Signalman Roose FUR 30/11/1875 Entered service on 20/- 1875 26 FR Staff Register Dacre Richard Signalman Roose FUR 10/03/1876 Resigned 1875 26 FR Staff Register Dacre Robert Porter Whitehaven Preston St FUR 25/11/1867 Entered service on 18/- 1867 24 FR Staff Index 1845-1873 Dacre Robert Signalman Whitehaven Corkickle FUR 31/03/1868 Transferred from Preston St on 20/- 1867 24 FR Staff Index 1845-1873 Dacre Robert Pointsman Dalton FUR 00/11/1869 Transferred from Corkicle on 20/- 1867 25 FR Staff Index 1845-1873 Dacre Robert Pointsman Ulverston FUR 00/01/1870 From Dalton 1867 25 FR Staff Index 1845-1873 Transferred from Ulverston Resigned Dacre Robert Pointsman Carnforth FUR 00/01/1870 1867 25 FR Staff Index 1845-1873 Apr 1871 Dacre Robert Pointsman at Dock Basin Barrow Goods FUR 20/11/1871 Entered service on 20/- 1871 30 FR Staff Index 1845-1873 Moved from Barrow on 20/- 22/- Nov Dacre Robert Pointsman Furness Abbey FUR 00/03/1872 1871 30 FR Staff Index 1845-1873 1872 Resigned Feb 1873 Daffern G.W. -

Cumbria 3-2021.Xlsx

Lens of Sutton Association ‐ Cumbria Railways ‐ Transport Library List 2021 Neg Description 66291 41221 Ivatt 2MT waiting at Coniston Station, Furness Railway, circa 1950 (AW Croughton) 66420 LMS 70 Stanier 3P 2‐6‐2T waiting at Low Gill Station, Little Noth‐Western side, 1948 (AW Croughton) 66522 Keswick Station, Cockermouth, Keswick & Penrith Railway, circa 1950 (AW Croughton) 66744 FR 105 Pettigrew 0‐6‐2T and FR 4 Pettigrew 0‐6‐0 outside Lakeside Station, Furness Railway, circa 1920 68610 Millom Station, Furness Railway, with Barrow bound DMU circa 1967 90459 42457 Stanier 4MT on eastbound passenger service entering Arnside Station, 13/8/1953 90522 42134 Faiburn 4MT in Windermere branch platform at Oxenholme Station, circa 1965 AY165 45572 Jubilee class on northbound passenger service at Penrith Station, circa late 1950s AY171 45506 Patriot class on northbound passenger service at Penrith Station, circa late 1950s CFO429 LMS 11627 ex Furness Railway 0‐6‐2T inside Moor Row engine shed, 10/7/1935 (CF Oldham) CFO447 LMS 12497 ex Furness Railway 0‐6‐0 outside Workington engine shed, 12/7/1935 (CF Oldham) CFO448 LMS 8603 ex LNWR 'Cauliflower' class 0‐6‐0 outside Workington engine shed, 12/7/1935 (CF Oldham) CFO449 LMS 4007 ex MR 4F class 0‐6‐0 outside Workington engine shed, 12/7/1935 (CF Oldham) CFO1276 LMS 8369 ex LNWR 'Cauliflower' class 0‐6‐0 on eastbound passenger service at Keswick Station, on the Cockermouth, Keswick and Penrith Railway, 7/6/1939 (CF Oldham) CFO1277 LMS 8610 ex LNWR 'Cauliflower' class 0‐6‐0 on eastbound passenger service near Threlkeld, on the Cockermouth, Keswick and Penrith Railway, 6/1939 (CF Oldham) CFO1278 LMS 8551 ex LNWR 'Cauliflower' class 0‐6‐0 on passenger service near Embleton, on the Cockermouth, Keswick and Penrith Railway, 6/1939 (CF Oldham) JNF261‐7 66478 ex NBR class J35 leaving Carlisle Station with 3‐25 pm service to Silloth, 15/7/1956 (JN Faulkner) JNF261‐8 42376 Fowler 4MT awaiting departure from Coniston Station with the 12‐00 to Barrow, 18/7/1956. -

New Electoral Arrangements for Copeland Borough Council

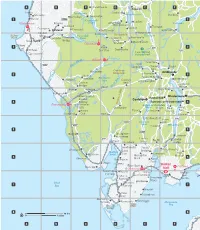

New electoral arrangements for Copeland Borough Council Final recommendations August 2018 Translations and other formats For information on obtaining this publication in another language or in a large-print or Braille version, please contact the Local Government Boundary Commission for England: Tel: 0330 500 1525 Email: [email protected] © The Local Government Boundary Commission for England 2018 The mapping in this report is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. Licence Number: GD 100049926 2018 Table of Contents Summary .................................................................................................................... 1 Who we are and what we do .................................................................................. 1 Electoral review ...................................................................................................... 1 Why Copeland? ...................................................................................................... 1 Our proposals for Copeland .................................................................................... 1 What is the Local Government Boundary Commission for England? ......................... 2 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 3 What is an electoral review? .................................................................................. -

Part 1 of the Bibliography Catalogue

Bibliography - L&NWR Society Periodicals Part 1 Titles - A to LNWR Registered Charity - L&NWRSociety No. 1110210 Copyright LNWR Society 2014 Title Year Volume Page American European News Letter Drawing of Riverside Station and notes on the new station 1895 Archive Industrial Railways and tramways of Flintshire. Maps 7 photos. Ffrith branch 1998 18 The Argus Poignant rememberance. Collision of SS.Connemara Nov 1916 2006 13/09 97 Menu Card from Greenore Hotel opening. 2007 03/07 30 Sale of Quay St. station building in Dundalk. 2007 03/07 76 Bournemouth Graphic F.W.Webb Obituary. The Bournemouth Graphic. 1906 06/14 Business History Labour and Business in Modern Britain British Railway Workshops 1838-1914 1989 31/02 8 Branch Line News Supplement No.7 to Branch Line News sheet. Branch lines closed 1964-68. Other changes. 1969 120A Yorkshire & the Humber (South Yorkshire) Sheffield LNWR Goods 2001 09/22 210 North West England. Wapping Branch and Former Lime St. Tunnel Ventilation Chimney 2004 08/21 187 Wales. Spelling discrepancies 2004 10/16 235 Yorkshire & the Humber. Kirkburton Branch 2004 11/13 259 Yorkshire & the Humber. Deighton 2004 11/21 269 Yorkshire & the Humber. Deighton 2005 01/12 7 Bahamas Locomotive Society Journal 'Basher' Tank No.1054 - an account of the automatic vacuum brake. 2007 62 14 Bluebell News Arrival on Bluebell Railway of Semi Royal Saloon No.806 on 10/10/2000 2000 10 British Railways Illustrated Chapel-en-le-Frith 1957. Accident 1992 01/02 141 UVC. The Way We Were. Incs photos of LNWR locos 1992 01/04 171 Station Survey. -

Land with Potential for Residential Development Frizington Cumbria Ca26

LAND WITH POTENTIAL FOR RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT ROWRAH FOR SALE FREEHOLD FRIZINGTON PRICE GUIDE £150,000 CUMBRIA CA26 3XJ • Site Area 0.79 hectares (1.95 acres) • Identified as suitable for residential development in the local plan • Former railway goods yard now scrubland with trees • West Cumbria village near Whitehaven and Cleator Moor • Offers invited Ref: MA1150 LOCATION SERVICES Rowrah is a residential village which lies on the A5086 road Interested parties will need to make their own enquiries between Cockermouth and Egremont in west Cumbria within a regarding connections to mains services. couple of miles of the western boundary of the Lake District National Park. The adjoining village of Arlecdon has a primary TENURE school and pub whilst Frizington, about 2 miles, has a We are advised the property is freehold. convenience store and other shops. The nearest main centre is the harbour town of Whitehaven, VAT & STAMP DUTY about 6 miles, which has supermarkets, a shopping centre and All reference to price, premium or rent are deemed to be marina. The area benefits from employment at the Sellafield exclusive of VAT unless expressly stated otherwise. Stamp duty reprocessing site, inward investment from Britains Energy is liable at the prevailing rates. An option to waive VAT Coast, a public sector partnership, and the proposed Moorside exemption has been made and VAT will be payable on the Nuclear Power Station would bring further significant purchase price. investment if it goes ahead. VIEWING DESCRIPTION The sites can be viewed from the adjoining highways and The land comprises the area shown edged red on the attached footpaths. -

# # # # # # Æ Æ Æ Æ Æ Æ Æ Æ # ÷ # # # # Æ Æ Æ

#\ A B C #\ Thackthwaite D #\ E F Keswick Lowca Swinside #\ #\ #\ Loweswater #\ Moresby Derwentwater Dockray #\ Lamplugh #\ Loweswater 1 #\ Parton 0¸A5086 1 Crummock #\ #\ #\ Lodore Whitehaven Rowrah Water Little Town Ullswater #\ Brackenburn #æ] #\Kirkland #\Thirlspot \# Frizington #\ Grange 1 #\ Kirkland Croasdale \# Buttermere Glenridding #\ 0¸B5345 Cleator #\ Watendlath St Bees #\ Buttermere Borrowdale Moor #\ Ennerdale Thirlmere Head #\ Parkside Ennerdale Water #\ Gatesgarth #\Rosthwaite #\ Bridge 3 0¸B5289 Moor Row \# #\ Stonethwaite Ennerdale #æ Seatoller St Bees # 2 #\ 2 Head Black #÷ 0¸A591 # #\ St Bees Sail YHA Seathwaite 0¸A592 Lake District Egremont #\ National Park ng Wasdale #æ#\ 2 Ble Grasmere r #\ 0¸A595 ve Great Ri Chapel Rydal Langdale #\ # #\ Stile Wastwater Cumbrian #\ n #\ Ambleside e Mountains Elterwater 3 h #] 3 E #\ Nether Skelwith Bridge#\ r Burnmoor k #\ #\ e #\ Wasdale s Waterhead v Gosforth Tarn Cockley i E Little Langdale R Santon er Beck \# Troutbeck #\ Bridge iv R Bridge Seascale#\ #\ Boot #\ y High Wray #\ Irton Eskdale e #\ l \# l Holmrook #\ a V #] #Ravenglass & #\ Windermere #\ on Hawkshead Eskdale d Coniston #] d #\ 4 Railway u Bowness-on-Windermere 4 #\ D #æ # Muncaster #\ Ravenglass 4 #\ Esthwaite Grizedale #\ Castle Seathwaite Water Forest Near Ferry #\ Broad Torver Grizedale #\ Sawrey Nab #\ #\ Lane End #\ Oak Ulpha#\ Winster #\ Satterthwaite Force 0¸A592 0¸A593 Coniston #\ Mills Water 0¸A595 Rusland Windermere #\ 5 5 0¸A5084 #\ Bootle Broughton- #\ #\ in-Furness Lakeside 0¸A595 Lowick Bouth #\ -

Abbey Town Aberford Abram Accrington Ackworth Moor Top

Abbey Town Astley Bickley Moss Brighouse Catterall Aberford Atherton Bidston Brigsteer Chadderton Abram Audlem Bierley Brinscall Chatburn Accrington Aughton Billinge Brisco Cheadle Ackworth Moor Top Ayle Bingley Broadheath Cheadle Hulme Acton Backford Birch Brockholes Checkley Addingham Bacup Birkenhead Bromborough Chelford Adel Baddiley Birkenshaw Bromfield Chequerbent Adlington Badsworth Birstall Bromley Cross Cherry Tree Adlington Baggrow Bispham Brough Chester Aigburth Baguley Blackburn Brough Sowerby Childwall Aikton Baildon Blackpool Broughton Chipping Ainsdale Balderstone Blackrod Broughton in Cholmondeley Ainstable Ballabeg Blencarn Furness Chorley Aintree Ballakinnag Blencogo Broughton Moor Christleton Aireborough Ballasalla Blencow Broxton Church Alderley Edge Bamber Bridge Blundellsands Bryn Church Coppenhall Alderley Park Bampton Bollington Bunbury Church Minshull Aldersey Banks Bolton Burgh by Sands Churwell Aldford Barbon Bolton by Bowland Burley in City Station Aldingham Bardsea Bolton le Sands Wharfedale Claughton Allgreave Bardsey Boltongate Burneside Claughton Allonby Bare Boot Burnley Clayton Almondbury Barkisland Bootle Burscough Clayton West Alsager Barnoldswick Bootle Burto-In-Kendal Clayton-le-Moors Alston Barrowford Borrowdale Burton Cleator Altham Barrow-in-Furness Borwick Burtonwood Cleator Moor Altofts Barthomley Bosley Bury Cleckheaton Altrincham Barton Boston Spa Busk Cleveleys Alvanley Barton Bothel Buttermere Cliburn Alverthorpe Barton upon Irwell Bowdon Buttershaw Clifton Ambleside Bassenthwaite Lake Bowland -

RCHS 2019 AGM Weekend Tour Notes

RAILWAY & CANAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY 2019 AGM WEEKEND Abbey House Hotel & Gardens, Abbey Road, Furness, Cumbria, LA13 0PA Programme & Tour Notes Page List of Members & Guests Attending 2 Programme for the Weekend 3 The pre-Railway Communications Challenge 4 The Barrow Story – A Brief History 5 th Friday 26 April – Ravenglass & Eskdale Railway, Millom & Askam 8 th Saturday 27 April – Ulverston, Ulverston Canal, Roa Island 22 th Sunday 28 April – Haverthwaite, Lakeside, Bowness, Backbarrow, Grange & Kents Bank 38 th Monday 29 April – Arnside, Kent Viaduct, Kendal Branch, Tewitfield, Carnforth 52 Welcome to the 2019 RCHS AGM Weekend organized by the NW Group Committee. These pages of notes are intended to add to your knowledge and/or remind you of the areas we shall be visiting during the four coach tours. Where maps have been included, these are not intended to be replacements for the source maps, but to aid location of sites on shown on OS, Alan Godfrey, and other maps. In producing the notes, a number of publications have proven to be useful - Those we have relied on most are: A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain vol 14, David Joy (David & Charles, 1993) An Introduction to Cumbrian Railways, David Joy (Cumbrian Railways Assoc., 2017) Railway Passenger Stations in Great Britain: A Chronology, Michael Quick (Railway & Canal Historical Society, 2009) The Furness Railway, K J Norman (Silver Link, 1994) The Furness Railway: a history, Michael Andrews (Barrai Books, 2012) The Furness Railway in and around Barrow, Michael Andrews (Cumbrian Railways Assoc., 2003) The Railways of Carnforth, Philip Grosse (Barrai Books, 2014) The Railways of Great Britain: A Historical Atlas, Col M H Cobb (Ian Allan, 2005) The Ulverstone and Lancaster Railway, Leslie R Gilpin (Cumbrian Railways Assoc., 2008) Maps of the area, both current and historical, include: O.S. -

Engineer and Engineering up to 09 June 2015.Xlsx

Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Society Electronic Journal Reading Project 1 of 265 Original Key words, names, Type of print Page Brief description of article Author of articleTitle of article or phrases in article article source Volume Number Date Electronic source William Barker sued the LYR for £4 for breach of contract and lost time. He booked on the 7.40 pm Pontefract - Huddersfield train. The train was delayed by an accident and Barker missed his connection. He couldn’t be guaranteed a later connection so hired a chaise costing £1. 10s. 6d. The LYR said it could not be responsible as the delay was unforeseen (this was printed on the back of tickets). The judge agreed with Baker Important Decision awarding the £1. 10s. 6d (but not the remainder for 'lost Affecting Railway LYR, Huddersfield The time'). Travellers Court, William Barker, News Engineer 1 120 1856/03/07 http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/The_Engineer_1856/03/07 East Lancashire Railway order for rails and chairs for an Prices Current of The extension. Metals ELR Business Engineer 1 174 1856/03/28 http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/The_Engineer_1856/03/28 East Lancashire Railway in the market for ironwork in Prices Current of The support of a new extension. Metals ELR Business Engineer 1 201 1856/04/11 http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/The_Engineer_1856/04/11 Institution of Civil Engineers discussion on 'steep gradients of railways' (I.K. Brunel in the Chair). Reference to Oldham Incline, 1.5 miles at 1 in 27 gradient. A 27 ton tank engine drew a train of 'nine loaded carriages weighing 50 tons' at 15 mph up the incline.