HHS Public Access Author Manuscript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eucalyptol (1,8 Cineole) from Eucalyptus As COVID-19 Mpro Inhibitor

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 31 March 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202003.0455.v1 Eucalyptol (1,8 cineole) from eucalyptus as COVID-19 Mpro inhibitor. However, essential oil a potential inhibitor of further research is necessary to investigate COVID 19 corona virus infection by their potential medicinal use. Molecular docking studies Arun Dev Sharma* and Inderjeet Kaur Keywords: COVID-19, Essential oil, Eucalyptol, Molecular docking PG dept of Biotechnology, Lyallpur Khalsa College Jalandhar *Corresponding author, e mail: [email protected] Graphical abstract Abstract Background: COVID-19, a member of corona virus family is spreading its tentacles across the world due to lack of drugs at present. Associated with its infection are cough, fever and respiratory problems causes more than 15% mortality worldwide. It is caused by a positive, single stranded RNA virus from the enveloped coronaviruse family. However, the main viral proteinase (Mpro/3CLpro) has recently been regarded as a suitable target for drug design against SARS infection due to its vital role in polyproteins processing necessary for coronavirus reproduction. Objectives: The present in silico study was designed to evaluate the effect of Eucalyptol (1,8 cineole), a essential oil component from eucalyptus oil, on Mpro by docking study. Methods: In the present study, molecular docking studies were conducted by using 1- click dock and swiss dock tools. Protein interaction mode was calculated by Protein Interactions Calculator. Results: The calculated parameters such as RMSD, binding energy, and binding site similarity indicated effective binding of eucalyptol to COVID-19 proteinase. Active site prediction further validated the role of active site residues in ligand binding. -

The Direct and Functional Interaction of Tubulin with Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 2

The Direct and Functional Interaction of Tubulin With Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 2 by Colin Elliott Seepersad A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Masters of Science Cell & Systems Biology University of Toronto © Copyright by Colin Elliott Seepersad 2011 The Direct and Functional Interaction of Tubulin With Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 2 Colin Elliott Seepersad Masters of Science Cell & Systems Biology University of Toronto 2011 Abstract Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 2 (TRPM2) is a widely expressed, non-selective cationic channel with implicated roles in cell death, chemokine production and oxidative stress. This study characterizes a novel interactor of TRPM2. Using fusion proteins comprised of the TRPM2 C-terminus we established that tubulin interacted directly with the predicted C-terminal coiled-coil domain of the channel. In vitro studies revealed increased interaction between tubulin and TRPM2 during LPS-induced macrophage activation and taxol-induced microtubule stabilization. We propose that the stabilization of microtubules in activated macrophages enhances the interaction of tubulin with TRPM2 resulting in the gating and/or localization of the channel resulting in a contribution to increased intracellular calcium and downstream production of chemokines. ii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my supervisor Dr. Michelle Aarts for providing me with the opportunity to pursuit a Master’s of Science Degree at the University of Toronto. Since my days as an undergraduate thesis student, Michelle has provided me with the knowledge, tools and environment to succeed. I am very grateful for the experience and will move forward a more rounded and mature student. Special thanks to my committee members, Dr. -

Note: the Letters 'F' and 'T' Following the Locators Refers to Figures and Tables

Index Note: The letters ‘f’ and ‘t’ following the locators refers to figures and tables cited in the text. A Acyl-lipid desaturas, 455 AA, see Arachidonic acid (AA) Adenophostin A, 71, 72t aa, see Amino acid (aa) Adenosine 5-diphosphoribose, 65, 789 AACOCF3, see Arachidonyl trifluoromethyl Adlea, 651 ketone (AACOCF3) ADP, 4t, 10, 155, 597, 598f, 599, 602, 669, α1A-adrenoceptor antagonist prazosin, 711t, 814–815, 890 553 ADPKD, see Autosomal dominant polycystic aa 723–928 fragment, 19 kidney disease (ADPKD) aa 839–873 fragment, 17, 19 ADPKD-causing mutations Aβ, see Amyloid β-peptide (Aβ) PKD1 ABC protein, see ATP-binding cassette protein L4224P, 17 (ABC transporter) R4227X, 17 Abeele, F. V., 715 TRPP2 Abbott Laboratories, 645 E837X, 17 ACA, see N-(p-amylcinnamoyl)anthranilic R742X, 17 acid (ACA) R807X, 17 Acetaldehyde, 68t, 69 R872X, 17 Acetic acid-induced nociceptive response, ADPR, see ADP-ribose (ADPR) 50 ADP-ribose (ADPR), 99, 112–113, 113f, Acetylcholine-secreting sympathetic neuron, 380–382, 464, 534–536, 535f, 179 537f, 538, 711t, 712–713, Acetylsalicylic acid, 49t, 55 717, 770, 784, 789, 816–820, Acrolein, 67t, 69, 867, 971–972 885 Acrosome reaction, 125, 130, 301, 325, β-Adrenergic agonists, 740 578, 881–882, 885, 888–889, α2 Adrenoreceptor, 49t, 55, 188 891–895 Adult polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), Actinopterigy, 223 1023 Activation gate, 485–486 Aframomum daniellii (aframodial), 46t, 52 Leu681, amino acid residue, 485–486 Aframomum melegueta (Melegueta pepper), Tyr671, ion pathway, 486 45t, 51, 70 Acute myeloid leukaemia and myelodysplastic Agelenopsis aperta (American funnel web syndrome (AML/MDS), 949 spider), 48t, 54 Acylated phloroglucinol hyperforin, 71 Agonist-dependent vasorelaxation, 378 Acylation, 96 Ahern, G. -

Study of the Potential Synergistic Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oil Components Using the Thiazolyl Blue Tetrazolium Bromide (MTT) Assay T

LWT - Food Science and Technology 101 (2019) 183–190 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect LWT - Food Science and Technology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/lwt Study of the potential synergistic antibacterial activity of essential oil components using the thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay T ∗ Raquel Requena , María Vargas, Amparo Chiralt Institute of Food Engineering for Development, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was used to study the potential interactions between several Antimicrobial synergy active compounds from plant essential oils (carvacrol, eugenol, cinnamaldehyde, thymol and eucalyptol) when Listeria innocua used as antibacterial agents against Escherichia coli and Listeria innocua. The minimum inhibitory concentration Escherichia coli (MIC) of each active compound and the fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index for the binary combi- MIC nations of essential oil compounds were determined. According to FIC index values, some of the compound FIC index binary combinations showed an additive effect, but others, such as carvacrol-eugenol and carvacrol-cinna- maldehyde exhibited a synergistic effect against L. innocua and E. coli, which was affected by the compound ratios. Some eugenol-cinnamaldehyde ratios exhibit an antagonistic effect against E. coli, but a synergistic effect against L. innocua. The most remarkable synergistic effect was observed for carvacrol-cinnamaldehyde blends for both E. coli and L. innocua, but using different compound ratios (1:0.1 and 0.5:4 respectively for each bacteria). 1. Introduction some important foodborne fungal pathogens (Abbaszadeh, Sharifzadeh, Shokri, Khosravi, & Abbaszadeh, 2014). Carvacrol is also present in Foodborne pathogens and spoilage bacteria are the major concerns thyme EO, where thymol is the most abundant active compound. -

Template for Single Ingredient Monographs

NATURAL HEALTH PRODUCT COUNTERIRRITANTS This monograph is intended to serve as a guide to industry for the preparation of Product Licence Applications (PLAs) and labels for natural health product market authorization. It is not intended to be a comprehensive review of the medicinal ingredients. Definition of Counterirritant An externally applied substance that causes irritation or mild inflammation of the skin for the purpose of relieving pain in muscles or joints by reducing inflammation in deeper adjacent structures (Medline 2012; MediLexicon 2012; US FDA 1983). Notes Text in parentheses is additional optional information which can be included on the PLA and product label at the applicant’s discretion. The solidus (/) indicates that the terms and/or statements are synonymous. Either term or statement may be selected by the applicant. Date April 29, 2019 Proper name(s), Common name(s), Source material(s) Table 1. Proper name(s), Common name(s), Source material(s) – Medicinal ingredients Source ingredient(s) Source material(s)1 Proper name(s) Common name(s) Common name(s) Proper name(s) Part(s) 3-isothiocyanato-1- Allyl Allyl isothiocyanate N/A N/A propene isothiocyanate Allyl isothiocyanate Isothiocyanic acid allyl ester Ammonium hydroxide Ammonia water Ammonium N/A N/A Ammonium hydroxide hydroxide (1R, 4R)-1,7,7- (+)- Camphor d-camphor N/A N/A trimethylbicyclo[2.2. Camphor 1]heptan-2-one d-camphor d-camphor natural camphor (1RS, 4RS)-1,7,7- (+-)- camphor dl-camphor N/A N/A trimethylbicyclo[2.2. dl-camphor 1]heptan-2-one Racemic dl-camphor -

In Vitro Evaluation of the Whitening Effect of Mouth Rinses Containing Hydrogen Peroxide

Aesthetic Dentistry Restorative Dentistry In vitro evaluation of the whitening effect of mouth rinses containing hydrogen peroxide Abstract: The aim of this study was to evaluate the bleaching effect of two mouth rinses containing hydrogen peroxide. Thirty premolars were randomly Fábio Garcia Lima(a) Talita Aparecida Rotta(b) divided into two groups (n = 15): Listerine Whitening (LW) and Colgate Plax Sonara Penso(b) Whitening (PW). The teeth were fixed on a wax plate and with acrylic resin, (c) Sônia Saeger Meireles at a distance of 5 mm between each other, exposing the buccal surfaces. All Flávio Fernando Demarco(a) teeth were stored in artificial saliva for 45 days, being removed twice a day to be immersed for 1 min in each mouthwash, followed by 10-second wash- (a) Department of Restorative Dentistry, School ing in tap water. The pH of each product was measured. Digital images of of Dentistry, Federal University of Pelotas, each tooth were captured under standardized conditions. These images were Pelotas, RS, Brazil. cut in areas previously demarcated and analyzed in Adobe Photoshop 7.0 us- (b) Private practice, Joaçaba, SC, Brazil. ing the CIEL*a*b* color space system. Data were statistically analyzed by a (c) Department of Restorative Dentistry, School paired t test and an independent samples t test (p < 0.05). The pH values were of Dentistry, Federal University of João 5.6 and 3.4 for LW and PW, respectively. Both treatment groups showed a de- Pessoa, João Pessoa, PB, Brazil. crease in the b* parameter (p < 0.01), but a decrease of a* was observed only for PW (p < 0.01). -

Camphor and Eucalyptol—Anticandidal Spectrum, Antivirulence Effect, Efflux Pumps Interference and Cytotoxicity

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Camphor and Eucalyptol—Anticandidal Spectrum, Antivirulence Effect, Efflux Pumps Interference and Cytotoxicity Marija Ivanov 1,* , Abhilash Kannan 2, Dejan S. Stojkovi´c 1 , Jasmina Glamoˇclija 1 , Ricardo C. Calhelha 3 , Isabel C. F. R. Ferreira 3 , Dominique Sanglard 2 and Marina Sokovi´c 1 1 Department of Plant Physiology, Institute for Biological Research “Siniša Stankovi´c”—NationalInstitute of Republic of Serbia, University of Belgrade, Bulevar Despota Stefana 142, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] (D.S.S.); [email protected] (J.G.); [email protected] (M.S.) 2 Institute of Microbiology, University Hospital Lausanne and University Hospital Center, Rue du Bugnon 48, 1011 Lausanne, Switzerland; [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (D.S.) 3 Centro de Investigação de Montanha (CIMO), Instituto Politécnico de Bragança, Campus de Santa Apolónia, 5300-253 Bragança, Portugal; [email protected] (R.C.C.); [email protected] (I.C.F.R.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +381-11-207-84-19 Abstract: Candida albicans represents one of the most common fungal pathogens. Due to its increasing incidence and the poor efficacy of available antifungals, finding novel antifungal molecules is of great importance. Camphor and eucalyptol are bioactive terpenoid plant constituents and their antifungal properties have been explored previously. In this study, we examined their ability to inhibit the growth of different Candida species in suspension and biofilm, to block hyphal transition along with their impact on genes encoding for efflux pumps (CDR1 and CDR2), ergosterol biosynthesis (ERG11), and cytotoxicity to primary liver cells. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,585,961 B1 Stockel (45) Date of Patent: Jul

USOO6585961B1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 6,585,961 B1 Stockel (45) Date of Patent: Jul. 1, 2003 (54) ANTIMICROBIAL COMPOSITIONS 5,298.238 A 3/1994 Hussein 6,077,501. A * 6/2000 Sickora et al. (76) Inventor: Richard F. Stockel, 475 Rolling Hills 6.245,321 B1 * 6/2001 Nelson et al. Rd., Bridgewater, NJ (US) 08807 * cited by examiner (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this Primary Examiner-Christopher R. Tate patent is extended or adjusted under 35 U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. ASSistant Examiner Randall Winston (57) ABSTRACT (21) Appl. No.: 10/016,611 Aqueous antimicrobial and biofilm removal compositions, (22) Filed: Nov.30, 2001 comprising essential oils and certain cationic, anionic, 7 amphoteric or non-ionic Surfactants individually or in com (51) Int. Cl. ............................ A61K 7/16; A61 K 7/26; bination having hydrophile-lipophile balance (HLB) of A61K 7/24; A61K 35/78 about 16 or above are effective oral mouthwashes and (52) U.S. Cl. ........................... 424/49; 424/58; 424/725; topical antimicrobial Solutions. Optionally C, C, benzyl, 424/55; 424/742 3-phenylpropanol or 2-phenylethanol alcohols can be added (58) Field of Search ............................ 424/725, 49, 58, Singularly or in combination from about 2 to about 2OV/w %. 424/55, 742 Other optically ingredients include antimicrobial enhances (56) References Cited and biofilm removal agents e.g., chelating compounds and U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS certain organic acids. 4,657,758 A 4/1987 Goldemberg 5,174.990 A 12/1992 Douglas 21 Claims, No Drawings US 6,585,961 B1 1 2 ANTIMICROBAL COMPOSITIONS The carbon hydrogen - oxygen essential oils usually represent the more soluble portion of the oil. -

Thymol, Menthol and Eucalyptol As Agents for Microbiological Control in the Oral Cavity: a Scoping Review

Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Quím. Farm., Vol. 49(1), 44-69, 2020 www.farmacia.unal.edu.co Review article / http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/rcciquifa.v49n1.87006 Thymol, menthol and eucalyptol as agents for microbiological control in the oral cavity: A scoping review María Cecilia Martínez-Pabón1, Mailen Ortega-Cuadros2* School of Dentistry, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia. 1E-mail: [email protected]; ORCID: 0000-0002-8115-3089 2E-mail: [email protected]; ORCID: 0000-0002-4977-1709 Received: September 19, 2019 Accepted: April 3, 2020 Summary Dental plaque is a complex environment that maintains a balance with certain micro- bial communities; however, this microhabitat can be disturbed by some endogenous species causing disease. An exploratory systematic review was carried out using the PubMed, Scopus, Lilacs, and Science Direct databases, identifying that the thymol, menthol, and eucalyptol compounds present varying antimicrobial activity, intra- and interspecies discordance, and a strong antimicrobial intensity on Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Candida albicans, Candida dubliniensis, Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli, Lactobacillus plantarum, and Streptococcus mutans, indicating that these phytochemicals can be considered broad-spectrum antimicrobial substances, with an effect on microorganisms linked to oral diseases. Key words: Oral health, terpenes, phytochemicals. 44 Thymol, menthol and eucalyptol for microbiological control in the oral cavity Resumen Timol, mentol y eucaliptol como agentes para el -

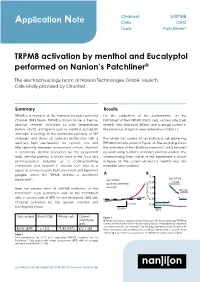

Application Note TRPM8 Activation by Menthol and Eucalyptol Performed

Channel: hTRPM8 Application Note Cells: CHO Tools: Patchliner® TRPM8 activation by menthol and Eucalyptol performed on Nanion’s Patchliner® The electrophysiology team at Nanion Technologies GmbH, Munich. Cells kindly provided by Chantest. Summary Results TRPM8 is a member of the transient receptor potential For the evaluation of the performance on the channel (TRP) family. TRPM8 is known to be a thermo- Patchliner® of the hTRPM8 (CHO) cells, success rate (cells sensitive channel, activated by cold temperatures sealed), seal resistance (RSeal) and average current in (below ~25˚C) and ligands such as menthol, Eucalyptol the presence of agonist were determined (Table 1). and icilin. It belongs to the melastatin subfamily of TRP channels1 and shows an outward rectification with a The whole cell current of an individual cell expressing relatively high permeability for calcium ions and TRPM8 channel is shown in Figure 1A. The recording shows little selectivity between monovalent cations. Menthol, the activation of the TRPM8 by menthol (1 mM) followed a secondary alcohol produced by the peppermint by wash using Nanion’s standard external solution. The herb, Mentha piperita, is widely used in the food and corresponding time course of the experiment is shown pharmaceutical industries as a cooling/soothing in Figure 1B. The current elicited by menthol was fully compound and odorant. It induces Ca2+ influx in a reversible upon washout. subset of sensory neurons from dorsal root and trigeminal ganglia, where the TRPM8 channel is specifically A B 2.5 2,3 Menthol expressed . control 2.0 1 mM 1mM Menthol Here we present data of hTRPM8 collected on the wash 1.5 Wash Patchliner®. -

Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, Treasury § 21.65

Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, Treasury § 21.65 210. External pharmaceuticals, not U.S.P. Eucalyptol, N.F. XII. or N.F. Eucalyptus oil, N.F. 450. Cleaning solutions (including household Eugenol, U.S.P. detergents). Guaiacol, N.F. X. Lavender oil, N.F. (2) As a raw material: Menthol, U.S.P. 530. Ethylamines. Methyl salicylate, N.F. 540. Dyes and intermediates. Mustard oil, volatile (allyl isothiocyanate), 579. Other chemicals. U.S.P. XII. Peppermint oil, N.F. (3) Miscellaneous uses: Phenol, U.S.P. Phenyl salicylate (salol), N.F. XI. 812. Product development and pilot plant Pine oil, N.F. XII. uses (own use only). Pine needle oil, dwarf, N.F. Rosemary oil, N.F. XII. § 21.64 Formula No. 37. Safrole. (a) Formula. To every 100 gallons of Sassafras oil, N.F. XI. alcohol add: Spearmint oil, N.F. Spearmint oil, terpeneless. Forty-five fluid onces of eucalyptol, N.F. Spike lavender oil, natural. XII, 30 avoirdupois ounces of thymol, N.F., Storax, U.S.P. and 20 avoirdupois ounces of menthol, Thyme oil, N.F. XII. U.S.P. Thymol, N.F. Tolu balsam, U.S.P. (b) Authorized uses. (1) As a solvent: Turpentine oil, N.F. XI. 111. Hair and scalp preparations. If it is shown that none of the above 112. Bay rum. single denaturants or combinations can 113. Lotions and creams (hand, face, and be used in the manufacture of a par- body). ticular product, the user may submit 131. Dentifrices. 132. Mouth washes. an application to the appropriate TTB 210. -

Capsaicin: Current Understanding of Its Mechanisms and Therapy of Pain and Other Pre-Clinical and Clinical Uses

molecules Review Capsaicin: Current Understanding of Its Mechanisms and Therapy of Pain and Other Pre-Clinical and Clinical Uses Victor Fattori †, Miriam S. N. Hohmann †, Ana C. Rossaneis, Felipe A. Pinho-Ribeiro and Waldiceu A. Verri Jr. * Departamento de Ciências Patológicas, Centro de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Rodovia Celso Garcia Cid KM480 PR445, Caixa Postal 10.011, 86057-970 Londrina, Paraná, Brazil; [email protected] (V.F.); [email protected] (M.S.N.H.); [email protected] (A.C.R.); [email protected] (F.A.P.-R.) * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +55-43-3371-4979 † These authors contributed equally to this paper. Academic Editor: Pin Ju Chueh Received: 27 April 2016; Accepted: 27 April 2016; Published: 28 June 2016 Abstract: In this review, we discuss the importance of capsaicin to the current understanding of neuronal modulation of pain and explore the mechanisms of capsaicin-induced pain. We will focus on the analgesic effects of capsaicin and its clinical applicability in treating pain. Furthermore, we will draw attention to the rationale for other clinical therapeutic uses and implications of capsaicin in diseases such as obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular conditions, cancer, airway diseases, itch, gastric, and urological disorders. Keywords: analgesia; capsaicinoids; chili peppers; desensitization; TRPV1 1. Introduction Capsaicin is a compound found in chili peppers and responsible for their burning and irritant effect. In addition to the sensation of heat, capsaicin produces pain and, for this reason, is an important tool in the study of pain. Although our understanding of pain mechanisms has evolved greatly through the development of new techniques, experimental tools are still extremely necessary and widely used.