History of the HPL (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victorian Marathon Club Newsletter

s v m m m 1973, 20 CENTS REGISTERED FOR POSTING AS A PERIODICAL - CA.TEGORT B. IMS V1C10RIAN MARATION CLUB i'&VvSLE 13 PUIiLlSHEi; FOB IhE INFORMATION OF MEMBERS OF iiirj v .W.C. AND OTHER PEOPLE j-'-iSHiSSIiL JM DISTANCE RUNNING Affi) IK ATHLETICS iNGEiMEiw' THft V.K*C» NEWSLETTER IS THE EDITORIAL REoFONSlBILIlT OF TH?- SECRETARY OK BEkaLF OF THE MEMBERS OF THE V.M.C. It is issued four times a year, corresponding to the Jasons of SPRING SUMMER AUTUMN WINTER, All keen athletic people ara invited to contribute letter*, results, comments, eto. whioh they feel are of interest to the sport and which would serve to provide information and a better understanding of athletics and the world of sport. Intending contributors are ask*d to note - MATERIAL FOR PUBLICATION MUST BE SUBMITTED IN SINGLE SPAT^m yyyRn FOOLSCAP irren ^ C^im e*0^ ^ nith' but U is suggested th^t ‘articles should not exceed ONE AND A HALF PAGES OF FOOLSCAP, and so keep editing to a ArtxC}fS.for p,jblioation l‘rJ^ be accompanied by the name and address of the contributor, together with his signature. The writer of the article shall retain full responsibility for the contents of the article. DEADLINE FOR COPY - THE 15th M X OF FEBRUARY. MAI. AUGUST. NOVEMBER. THE VICTORIAN MARATHON CLUB IS - OPEN FOR MEKTiRSHlP For any registered athlete COSTS $1,00 per annum for Seniors $0.50 per annum for Juniors (Under 19) CHARGES 50^ Kaoe Fee for each event AWARDS TROPHY ORDSRS FOR THE FTRST THREE PLACEGETTERS IN EVERY HANDICAP, ALSO TO THE COMPETITORS GAINING THE THREc; FASTEST TIMES IK THESE EVENTS. -

Northern California Distance Running Annual

1970 NORTHERN C a lifo rn ia distance RUNNING ANNUAL WEST VALLEY TRACK CLUB PUBLICATIONS $2. 00 1970 NORTHERN CALIFORNIA DISTANCE RUNNING ANNUAL A WEST VALLEY TRACK CLUB PUBLICATION EDITOR: JACK LEYDIG 603 SO. ELDORADO ST. SAN MATEO, CALIF. 94402 RICH DELGADO: TOP PA-AAU LONG DISTANCE RUNNER FOR 1970. l CONTENTS PHOTO CREDITS......................... 3 PREFACE.............................. 5 1970 PA-AAU CROSS COUNTRY TEAM.......... 6 HIGHLIGHTS............................. ll WINNERS OF 1970 PA-AAU RACES............ 21 1970 MARATHON LIST.................... 22 THE SENIORS........................... 25 14 AND UNDER.......................... 35 WOMEN................................ 38 CLUBS................................. 44 THE RUNNER'S HELPER..................... 47 A CROSS SECTION....................... 52 HIGH SCHOOL........................... 59 COLLEGIATE............................ 63 CONCLUSION............................ 67 1971 LONG DISTANCE SCHEDULE..............68 PA-AAU CLUB DIRECTORY.................. 71 OTHER IMPORTANT ADDRESSES.............. 74 NOTES................................ 75 ADVERTISEMENTS FOR RUNNING EQUIPMENT 77 PHOTO CREDITS I wish to thank all those individuals who contributed photos for the Annual. Some of those you sent, of course, were not used. We tried to use the best quality photos of those we received, although in some cases we had to make do with what we had. Below is a list of photo credits for each picture in this book. In some cases we didn't know who took the shot, but instead listed the individual -

March/April 2019 43 Years of Running Vol

March/April 2019 43 Years of Running Vol. 45 No. 2 www.jtcrunning.com ISSUE #433 NEWSLETTER TRACK SEASON BEGINS The Starting Line LETTER FROM THE EDITOR JTC Running’s gala event of the year, the Gate River picked off by Jay, Rodney and anyone else who was in Run, is now behind us, and what a race it was. It couldn’t the mood. I think Jay must have been the person who have gone any smoother and the weather could hardly coined the famous phrase “even pace wins the race.” Jay have been finer. I shouldn’t really call it just a race for was a human metronome. it is far more than that. Even the word event seems Curiously, when Rodney and I jogged we left Jay behind, inadequate. It is a massive gathering, a party, an expo, but every time we took walking “breaks” we found Jay a celebration and, oh yes, five quite different races. way out in front of us disappearing into the crowd. Jay’s Accolades and thanks must go to race director, Doug walking pace seemed faster than his running speed and Alred, and his efficient staff. Jane Alred organized a we couldn’t keep up. I suggested a new athletic career for perfect expo, as usual. Jay in race walking. He could do it. Now in his 70s, he We must never forget all our wonderful volunteers who still runs 50 miles a week. I was astonished, even if he made the GRR what it was. They do so year after year did add: “Some of it is walking.” The man is unstoppable. -

Table of Contents

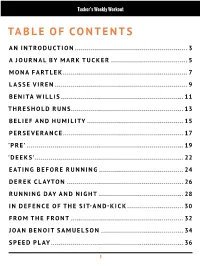

Tucker’s Weekly Workout TABLE OF CONTENTS AN INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 3 A JOURNAL BY MARK TUCKER ...................................... 5 MONA FARTLEK .............................................................. 7 LASSE VIREN .................................................................. 9 BENITA WILLIS ............................................................. 11 THRESHOLD RUNS........................................................ 13 BELIEF AND HUMILITY ................................................ 15 PERSEVERANCE ............................................................ 17 'PRE' .............................................................................. 19 'DEEKS' .......................................................................... 22 EATING BEFORE RUNNING .......................................... 24 DEREK CLAYTON .......................................................... 26 RUNNING DAY AND NIGHT .......................................... 28 IN DEFENCE OF THE SIT-AND-KICK ............................ 30 FROM THE FRONT ........................................................ 32 JOAN BENOIT SAMUELSON ......................................... 34 SPEED PLAY .................................................................. 36 2 Tucker’s Weekly Workout AN INTRODUCTION There is no one size fits all when it comes to training. We all have different biomechanics, psychology, motivations, backgrounds, personalities and general life situations that it would be foolish to think -

Table of Contents

A Column By Len Johnson TABLE OF CONTENTS TOM KELLY................................................................................................5 A RELAY BIG SHOW ..................................................................................8 IS THIS THE COMMONWEALTH GAMES FINEST MOMENT? .................11 HALF A GLASS TO FILL ..........................................................................14 TOMMY A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS ........................................................17 NO LIGHTNING BOLT, JUST A WARM SURPRISE ................................. 20 A BEAUTIFUL SET OF NUMBERS ...........................................................23 CLASSIC DISTANCE CONTESTS FOR GLASGOW ...................................26 RISELEY FINALLY GETS HIS RECORD ...................................................29 TRIALS AND VERDICTS ..........................................................................32 KIRANI JAMES FIRST FOR GRENADA ....................................................35 DEEK STILL WEARS AN INDELIBLE STAMP ..........................................38 MICHAEL, ELOISE DO IT THEIR WAY .................................................... 40 20 SECONDS OF BOLT BEATS 20 MINUTES SUNSHINE ........................43 ROWE EQUAL TO DOUBELL, NOT DOUBELL’S EQUAL ..........................46 MOROCCO BOUND ..................................................................................49 ASBEL KIPROP ........................................................................................52 JENNY SIMPSON .....................................................................................55 -

THE SPARTAN Reg No A0043579R CLUB PATRON - Robert De Castella June, 2013

THE SPARTAN Reg No A0043579R CLUB PATRON - Robert de Castella June, 2013 Websites References Club Contacts www.melbournemarathon.com.au Melbourne Marathon site www.melbournemarathonspartans.com Melbourne Marathon Spartans President [email protected] www.coolrunning.com.au Best Australian Runners Site Jay Fleming Phone: 9758 3161 www.vicmastersaths.org.au Victorian Masters Athletics www.athsvic.org.au Athletics Victoria www.athletics.org.au Athletics Australia Secretary www.vrr.org.au Victorian Road Runners [email protected] www.aura.asn.au/ Australian Ultra Runners Assoc www.ausrun.com.au Australian Runners World Treasurer www.run4yourlife.com.au Run For Your Life www.traralgonmarathon.org.au Traralgon Marathon Site Rod Bayley [email protected] www.sixfoot.com 45 kms pleasure & pain www.ausrunning.net Races and marathon results Postal Address www.mymarathonclub.com Listing Australasian marathons P.O. Box 162., Rosanna. Vic. 3084 Enquiries: [email protected] Life Members Paul Basile, Peter Battrick, John Dean, John Dobson, Peter Feldman, Christine Hodges, Ken Matchett Dec’d, Conor Mc Niece, John Raskas, Ron Young, Shirley Young, Peter Ryan, Maureen Wilson FROM THE PRESIDENT Annual General Meeting 16 September 2013 Venue – Harrison Room - MCG Time: 7.30 p.m. Guest Speaker: Tristan Miller Hi Spartans At each of our past six Annual General Meetings we have enjoyed the company of legends of Australian Sport in Tom Hafey, Steve Moneghetti, Tim O’Shaughnessy, Derek Clayton, Magnus Michelsson and Rob de Castella and I’m pleased to advise that this year will be no different. I have pleasure in confirming that our Headline Guest Speaker at this year’s AGM is none other than the remarkable Tristan Miller. -

2004 USA Olympic Team Trials: Men's Marathon Media Guide Supplement

2004 U.S. Olympic Team Trials - Men’s Marathon Guide Supplement This publication is intended to be used with “On the Roads” special edition for the U.S. Olympic Team Trials - Men’s Marathon Guide ‘04 Male Qualifier Updates in 2004: Stats for the 2004 Male Qualifiers as of OCCUPATION # January 20, 2004 (98 respondents) Athlete 31 All data is for ‘04 Entrants Except as Noted Teacher/Professor 16 Sales 13 AVERAGE AGE Coach 10 30.3 years for qualifiers, 30.2 for entrants Student 5 (was 27.5 in ‘84, 31.9 in ‘00) Manager 3 Packaging Engineer 1 Business Owner 2 Pediatrician 1 AVERAGE HEIGHT Development Manager 2 Physical Therapist 1 5’'-8.5” Graphics Designer 2 Planner 1 Teacher Aide 2 AVERAGE WEIGHT Researcher 1 U.S. Army 2 140 lbs. Systems Analyst 1 Writer 2 Systems Engineer 1 in 2004: Bartender 1 Technical Analyst 1 SINGLE (60) 61% Cardio Technician 1 Technical Specialist 1 MARRIED (38) 39% Communications Specialist 1 U.S. Navy Officer 1 Out of 98 Consultant 1 Webmaster 1 Customer Service Rep 1 in 2000: Engineer 1 in 2000: SINGLE (58) 51% FedEx Pilot 1 OCCUPATION # MARRIED (55) 49% Film 1 Teacher/Professor 16 Out of 113 Gardener 1 Athlete 14 GIS Tech 1 Coach 11 TOP STATES (MEN ONLY) Guidance Counselor 1 Student 8 (see “On the Roads” for complete list) Horse Groomer 1 Sales 4 1. California 15 International Ship Broker 1 Accountant 4 2. Michigan 12 Mechanical Engineer 1 3. Colorado 10 4. Oregon 6 Virginia 6 Contents: U.S. -

LE STATISTICHE DELLA MARATONA 1. Migliori Prestazioni Mondiali Maschili Sulla Maratona Tabella 1 2. Migliori Prestazioni Mondial

LE STATISTICHE DELLA MARATONA 1. Migliori prestazioni mondiali maschili sulla maratona TEMPO ATLETA NAZIONALITÀ LUOGO DATA 1) 2h03’38” Patrick Makau Musyoki KEN Berlino 25.09.2011 2) 2h03’42” Wilson Kipsang Kiprotich KEN Francoforte 30.10.2011 3) 2h03’59” Haile Gebrselassie ETH Berlino 28.09.2008 4) 2h04’15” Geoffrey Mutai KEN Berlino 30.09.2012 5) 2h04’16” Dennis Kimetto KEN Berlino 30.09.2012 6) 2h04’23” Ayele Abshero ETH Dubai 27.01.2012 7) 2h04’27” Duncan Kibet KEN Rotterdam 05.04.2009 7) 2h04’27” James Kwambai KEN Rotterdam 05.04.2009 8) 2h04’40” Emmanuel Mutai KEN Londra 17.04.2011 9) 2h04’44” Wilson Kipsang KEN Londra 22.04.2012 10) 2h04’48” Yemane Adhane ETH Rotterdam 15.04.2012 Tabella 1 2. Migliori prestazioni mondiali femminili sulla maratona TEMPO ATLETA NAZIONALITÀ LUOGO DATA 1) 2h15’25” Paula Radcliffe GBR Londra 13.04.2003 2) 2h18’20” Liliya Shobukhova RUS Chicago 09.10.2011 3) 2h18’37” Mary Keitany KEN Londra 22.04.2012 4) 2h18’47” Catherine Ndereba KEN Chicago 07.10.2001 1) 2h18’58” Tiki Gelana ETH Rotterdam 15.04.2012 6) 2h19’12” Mizuki Noguchi JAP Berlino 15.09.2005 7) 2h19’19” Irina Mikitenko GER Berlino 28.09.2008 8) 2h19’36’’ Deena Kastor USA Londra 23.04.2006 9) 2h19’39’’ Sun Yingjie CHN Pechino 19.10.2003 10) 2h19’50” Edna Kiplagat KEN Londra 22.04.2012 Tabella 2 3. Evoluzione della migliore prestazione mondiale maschile sulla maratona TEMPO ATLETA NAZIONALITÀ LUOGO DATA 2h55’18”4 Johnny Hayes USA Londra 24.07.1908 2h52’45”4 Robert Fowler USA Yonkers 01.01.1909 2h46’52”6 James Clark USA New York 12.02.1909 2h46’04”6 -

Run to the Library

Run to Your Library! Selected Titles about Running in the Marin County Free Library April 2009 Kick Asphalt! ChiRunning: A Revolutionary Approach to Effortless, Injury-Free Running by Danny Dreyer (2004) • 796.42 Dreyer Dreyer, a nationally ranked ultra-marathoner, presents a training program that utilizes principles from other disciplines such as yoga, t‟ai chi, and Pilates to enable runners to run faster and farther without getting hurt. Daniels' Running Formula by Jack Daniels (2nd ed/2005) • 796.42 Daniels Daniels, noted track and cross-country coach and advisor to Olympic and other world- class athletes, provides different programs for better running performance in distances ranging from 800 meters to the marathon. The Elements of Effort: Reflections on the Art and Science of Running by John Jerome (1997) • 796.42 Jerome, a published author and seasoned runner, addresses all aspects of running with wit and passion and a nod to the classic writer‟s reference, The Elements of Style, by Struck and White. Fun on Foot in America's Cities by Warwick Ford (2006) • 917.304 Ford Going out of town? That‟s no reason not to run, particularly if the destination is one of the 14 major cities included in Warwick‟s book with descriptions of 50 running routes and such information as local history, points of interest, and public transit. Sixty-four maps and 125 photographs supplement the book. Healthy Runner's Handbook by Lyle J. Micheli (1996) • 796.42 Micheli A sports doctor with over 20 years of experience treating injured runners, Micheli describes the diagnosis of, and rehabilitation from, 31 individual overuse injuries. -

Victorian Marathon Club Newsletter Is Published for the Information of Members of the V.M.C

SPRING 1971 VOL. 3. No. 2 ------------- V. M. C. NEWSLETTER -------------- ----------------------- SEPTEMBER, 1971 REGISTERED FOR POSTING AS A PERIODICAL - CATEGORY B. THE VICTORIAN MARATHON CLUB NEWSLETTER IS PUBLISHED FOR THE INFORMATION OF MEMBERS OF THE V.M.C. AND OTHER PEOPLE INTERESTED IN DISTANCE RUNNING AND IN ATHLETICS IN GENERAL The V.M.C. Newsletter is the Editorial responsibility of the Secretary on behalf of the members of the V.M.C. It is issued four times a year, corresponding to the Seasons of Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter* All keen athletic people are invited to contribute letters, results, comments, etc. which they feel are of interest to ths sport and which would serve to provide information and a better understanding of athletics and the world of sport. Intending contributors are asked to note that MATERIAL FOR PUBLICATION must be SUBMITTED ON SINGLE SPACED TYPED FOOLSCAP, irrespective of length, but it is suggested that articles should not exceed ONE AND A HALF PAGES OF FOOLSCAP AND SO KEEP EDITONG TO A MINIMUM. Articles for publication MUST be accompanied by the name and address of the contributor, together with his signature. The writer of the article shall retain full responsibility for the contents of the article. DEADLINES FOR COPY ARE ON THE 15th OF FEBRUARY. MAY. AUGUST and NOVEMBER. THE VICTORIAN MARATHON CLUB ISs OPEN TO MEMBERSHIP for any registered amateur athlete. COSTS $1.00 per annum for Seniors, $0.50 per annum for Juniors (Under 19) CHARGES 40^ Race Fee for each event. Aif'jiiRDS TROPHY ORDERS for the first three placegetters in every handicap, and to the competitor gaining fastest time in each of these events. -

1974 Age Records

TRACK AGE RECORDS NEWS 1974 TRACK & FIELD NEWS, the popular bible of the sport for 21 years, brings you news and features 18 times a year, including twice a month during the February-July peak season. m THE EXCITING NEWS of the track scene comes to you as it happens, with in-depth coverage by the world's most knowledgeable staff of track reporters and correspondents. A WEALTH OF HUMAN INTEREST FEATURES involving your favor ite track figures will be found in each issue. This gives you a close look at those who are making the news: how they do it and why, their reactions, comments, and feelings. DOZENS OF ACTION PHOTOS are contained in each copy, recap turing the thrills of competition and taking you closer still to the happenings on the track. STATISTICAL STUDIES, U.S. AND WORLD LISTS AND RANKINGS, articles on technique and training, quotable quotes, special col umns, and much more lively reading complement the news and the personality and opinion pieces to give the fan more informa tion and material of interest than he'll find anywhere else. THE COMPREHENSIVE COVERAGE of men's track extends from the Compiled by: preps to the Olympics, indoor and outdoor events, cross country, U.S. and foreign, and other special areas. You'll get all the major news of your favorite sport. Jack Shepard SUBSCRIPTION: $9.00 per year, USA; $10.00 foreign. We also offer track books, films, tours, jewelry, and other merchandise & equipment. Write for our Wally Donovan free T&F Market Place catalog. TRACK & FIELD NEWS * Box 296 * Los Altos, Calif. -

December 1981 $1.25

National Masters Newsletter 40th Issue December 1981 $1.25 The only national publication devoted exclusively to track &"field and long distance running for men and women over age 30 1/rOOO Runners FOSTER, HAMES TOP MASTERS IN NEW YORK NEW YORK, Oct. 25—On a beautiful autumn morning, with the fall foliage near its peak and 15 televi sion cameras grinding away for a na tional TV audience, the top over- age-40 runners among the 17,000 par ticipants both turned out to be New Zealanders. Jack Foster, 49, and Robin Hames, 44, were the top male and female masters in the internationally famous race which saw 10 of the top 18 masters awards go to foreigners. The great Foster, who, at age 41 in 1973, ran the fastest marathorr ever by an over-age-40 individual, 2:11:19, gave away 9 valuable years to his com petition, yet still finished as Lst master in an excellent 2:23:55, over a minute faster than Allison Roe, who set a new women's world record of 2:25:19. A minute behind Foster, in 2:24:55 was Marco Benito, 41, of Italy. A re juvenated Fritz Mueller, 45, of New York City was the top U.S. resident among the masters in 2:25:49. The first Start of National Masters 5K In New Orleans Oct. 18. Oliver Marshall right) was 1st 40-44 In 16:01; Jim McClatchie (2805) 2nd 40-44; Phil conlinued of> page n (1480) was 1st In 30-34 group In 15:15; Ken Winn (Atlanta jersey, far Baker (2802) 3rd 40-44.