The California Geographer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arte Urbana Street Art

ROTEIRO TEMÁTICO / THEMATIC TOUR: Arte Urbana Street Art Este folheto faz parte da série Roteiros Temáticos. Vivencie e explore São Paulo em roteiros autoguiados que oferecem ou- tras 8 perspectivas da cidade: Roteiro Afro, Arquitetura pelo centro histórico, O Café e a História da Cidade, Cidade Criativa, Ecorrural, Futebol, Independência do Brasil e Mirantes. This brochure is part of the Thematic Tours series. Live and explore Sao Paulo through auto guided tours that provide 8 other perspectives of the city: Afro-Brazilian Tour, Architecture in Downtown, Coffee and the History of São Paulo City, Creative Concepção / Project: São Paulo Turismo City, Eco Rural, Football, Brazilian Independence and Vistas. Projeto Gráfico / Graphic Project: Rômulo Castilho Diagramação / Graphic Design: Max Print, Rene Perol www.cidadedesaopaulo.com Fotos /Photography: Binho Ribeiro, Caio Pimenta, Keko Pascuzzi, Priscilla Vilariño, Tinho Supervisão / Supervision: Fernanda Ascar, Paulo Amorim Conteúdo / Text Editing: Adriana Omuro, Luciana Conceição São Paulo Turismo S/A www.cidadedesaopaulo.com Av. Olavo Fontoura, 1209 www.spturis.com Parque Anhembi, São Paulo (SP), www.anhembi.com.br CEP 02012-021, Tel.: +5511 2226-0400 www.autodromointerlagos.com [email protected] www.visitesaopaulo.com O objetivo da São Paulo Turismo é promover a cidade de São Paulo de forma independente sem nenhum vínculo com os estabelecimentos mencionados. Algumas informações estão sujeitas a mudanças sem aviso prévio. / The goal of São Paulo Turismo is to promote the city of São Paulo in an independent way, and with no link to the establishments mentioned in this brochure. All the information in this brochure is subject to change without prior notice. -

Desmontando a Un Analisis, De Su Tecnica, Y De Su Obra

desmontando a un Analisis, de su tecnica, y de su obra Autor: Eduardo Aracil Campos Tutor: Francisco Javier Consuegra Panaligan Grado en Humanidades Curso académico 2018-2019 Desmontando a Banksy Eduardo Aracil Campos Título del trabajo: Desmontando a Banksy. Un análisis de su técnica y de su obra Firma del autor Firma del tutor académico Eduardo Aracil Campos Francisco Javier Consuegra Panaligan Trabajo de Fin de Grado Grado en Humanidades Facultad de Filosofía y Letras 2 Desmontando a Banksy Eduardo Aracil Campos Resumen La historia del arte urbano es la de la recuperación del espacio público de las ciudades por quienes realmente lo habitan, por aquellos que, en su vida rutinaria, en demasiadas ocasiones anodina, transitan por calles y barrios a menudo decadentes, desvencijados, abandonados… una suerte de figuras casi autómatas, fantasmales, que, sin embargo, al encontrarse con una obra de arte urbano salen de su aletargamiento y esbozan una sonrisa… o fruncen el ceño. En esta polaridad del arte urbano, en esa línea tan fina que separa vandalismo de arte, se mueve como pez en el agua Banksy, un artista que ha dado ese impulso definitivo que necesitaba el street art para presentarse ante la sociedad como un arte vanguardista, original, crítico y reflexivo, pero ante todo universal, accesible a todos los estratos sociales. Esa universalidad es la que representa Banksy y es el valor que el artista de Bristol da a su obra, una obra que, sin embargo, cada vez más frecuentemente es objeto de especulación por las galerías de arte y las casas de subasta. Podemos afirmar que Banksy es ya un fenómeno de masas del que se han escrito chorros de tinta y se han retuiteado miles de mensajes o compartido cientos de noticias. -

Beyond Guernica and the Guggenheim

Beyond Guernica and the Guggenheim Beyond Art and Politics from a Comparative Perspective a Comparative from Art and Politics Beyond Guernica and the Guggenheim This book brings together experts from different fields of study, including sociology, anthropology, art history Art and Politics from a Comparative Perspective and art criticism to share their research and direct experience on the topic of art and politics. How art and politics relate with each other can be studied from numerous perspectives and standpoints. The book is structured according to three main themes: Part 1, on Valuing Art, broadly concerns the question of who, how and what value is given to art, and how this may change over time and circumstance, depending on the social and political situation and motivation of different interest groups. Part 2, on Artistic Political Engagement, reflects on another dimension of art and politics, that of how artists may be intentionally engaged with politics, either via their social and political status and/or through the kind of art they produce and how they frame it in terms of meaning. Part 3, on Exhibitions and Curating, focuses on yet another aspect of the relationship between art and politics: what gets exhibited, why, how, and with what political significance or consequence. A main focus is on the politics of art in the Basque Country, complemented by case studies and reflections from other parts of the world, both in the past and today. This book is unique by gathering a rich variety of different viewpoints and experiences, with artists, curators, art historians, sociologists and anthropologists talking to each other with sometimes quite different epistemological bases and methodological approaches. -

Complete C.V

MICHAEL DE FEO mdefeo.com SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 198 Allen Street, Michael De Feo Flowers, New York, NY, Pop Up April 25 - 26 2016 Danziger Gallery, Michael De Feo, New York, NY, July 13 – August 12 2016 Rice Gallery, Rice University, Crosstown Traffic, Houston, Texas, June 9 – August 28 2016 Urban Art Fair, Michael De Feo, Paris, France, April 21 - 24 2016 The Garage, The Fashion Pages, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, April 8 - 29 2014 Rush Arts Gallery, A Pocket Full of Posies, New York, NY, September 4 - 20 2011 A’P’art: Le festival international d’art contemporain, Alpilles-Provence, France, July 12 – Aug. 17 2011 Children’s Museum of The Arts, Collaborative Mural, New York, NY, June – September 2011 Orange Dot Gallery, London, UK, Coming in from the Outside, March 8 -15 2010 A’P’art: Le festival international d’art contemporain, Alpilles-Provence, France, July 8 – 13 2010 No Borders Contemporary Art, Hong Kong, China, Mining for Splinters and Diamonds, June 24 – Aug.14 2009 Hollywood in Cambodia, Buenos Aires, Argentina, New Self-Portraits, April 21 2008 The Editions/Artists’ Book Fair, New York, NY, Aldrich Edition, Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Oct. 31 – Nov. 2 2008 Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico, Santurce, San Juan, Puerto Rico, Flowers (interior and exterior installations), Ongoing 2008 Manifesta 7, Trento, Italy, Flowers (outdoor installation on the Palazzina Liberty), June 21 – Nov. 2 2008 Another Space, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, Another Show, April 18 – 19 2007 OPEN SPACE Gallery, Beacon, NY, Inside Out, September 8 – Nov. 4 2007 Association le M.U.R., Paris, France, Olympia – Hommage au Manet (outdoor billboard painting installation), July 28 – Aug. -

Grafficity Visual Practices and Contestations in Urban Space

EVA YOUKHANA AND LARISSA FÖRSTER (EDS.) GRAFFICITY Visual Practices and Contestations in Urban Space MORPHOMATA Graffiti has its roots in urban youth and protest cul- tures. However, in the past decades it has become an established visual art form. This volume investigates how graffiti oscillates between genuine subversiveness and a more recent commercialization and appropria- tion by the (art) market. At the same time it looks at how graffiti and street art are increasingly used as an instrument for collective re-appropriation of the urban space and so for the articulation of different forms of belonging, ethnicity, and citizenship. The focus is set on the role of graffiti in metropolitan contexts in the Spanish-speaking world but also includes glimpses of historical inscriptions in ancient Rome and Meso- america, as well as the graffiti movement in New York in the 1970s and in Egypt during the Arab Spring. YOUKHANA, FÖRSTER (EDS.) — GRAFFICITY MORPHOMATA EDITED BY GÜNTER BLAMBERGER AND DIETRICH BOSCHUNG VOLUME 28 EDITED BY EVA YOUKHANA AND LARISSA FÖRSTER GRAFFICITY Visual Practices and Contestations in Urban Space WILHELM FINK unter dem Förderkennzeichen 01UK0905. Die Verantwortung für den Inhalt der Veröffentlichung liegt bei den Autoren. Umschlagabbildung: © Brendon.D Bibliografische Informationen der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek: Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen National biblio grafie; detaillierte Daten sind im Internet über www.dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. Alle Rechte, auch die des auszugsweisen Nachdrucks, der fotomechanischen Wiedergabe und der Übersetzung vorbehalten. Dies betrifft auch die Verviel fältigung und Übertragung einzelner Textabschnitte, Zeichnungen oder Bilder durch alle Verfahren wie Speicherung und Übertragung auf Papier, Transpa rente, Filme, Bänder, Platten und andere Medien, soweit es nicht § 53 und 54 UrhG ausdrücklich gestatten. -

Artists: Ben Frost, Noah Scalin, COPE, Hanksy, Rob Tarbell, David E

“Past to Present” – Artists: Ben Frost, Noah Scalin, COPE, Hanksy, Rob Tarbell, David E. Peterson, Chris Dean, Sangsik Hong. February 7th – March 4th Krause Gallery – www.krausegallery.com 149 Orchard St. NYC Opening Reception: February 7th, 6-9pm NEW YORK — Krause Gallery is excited to announce “Past to Present”, a Group Show. Past To Present showcases the perpetual growth of the artists. Each artist has a piece from their past as well as their present work on display. Growth and evolution in an artists work is necessary for their continual success, without such evolution their work becomes redundant. Ben Frost: (born Brisbane, Australia) is a visual artist whose work seeks to challenge contemporary norms and values of world culture and society. Frost’s visual work places common iconic images from advertising, consumerism, entertainment, and politics into startling juxtapositions that are often confrontational and controversial. He currently lives and works in Sydney, Australia, and exhibits locally and internationally. Frost has been exhibiting throughout Australia and internationally over the last 14 years, including solo shows in London, New York, and San Francisco, as well as group shows in Amsterdam, Berlin, Mongolia, and Singapore. In 2007, Frost participated in Tiger Translate in Beijing, collaborating with local Chinese artists. His work has appeared in countless magazines and newspapers including Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Oyster, WeAr, Monster Children, The Sydney Morning. COPE2: Fernando Carlo (also known as Cope2) is an artist from the Kingsbridge section of the Bronx, New York. He has been a graffiti artist since 1978-79, and has gained international credit for his work. -

Public Art in Public Space: Tracking Graffiti and Mural Art Practices in Contemporary Tehran

PUBLIC ART IN PUBLIC SPACE: TRACKING GRAFFITI AND MURAL ART PRACTICES IN CONTEMPORARY TEHRAN A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY SOLMAZ ZARE GHAREHGHESHLAGHI IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN URBAN DESIGN IN CITY AND REGIONAL PLANNING NOVEMBER 2019 Approval of the thesis: PUBLIC ART IN PUBLIC SPACE: TRACKING GRAFFITI AND MURAL ART PRACTICES IN CONTEMPORARY TEHRAN Submitted by SOLMAZ ZARE GHAREHGHESHLAGHI in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Urban Design in City and Regional Planning Department, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Halil Kalıpçılar Dean, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences Prof. Dr. Çağatay Keskinok Head of Department, City and Regional Planning Prof. Dr. Müge Akkar Ercan Supervisor, City and Regional Planning Dept, METU Examining Committee Members: Assist. Prof. Dr. Yücel Can Severcan City and Regional Planning Dept., METU Prof. Dr. Müge Akkar Ercan City and Regional Planning Dept., METU Assoc. Prof. Dr. Lale Özgenel Architecture Dept., METU Prof. Dr. Ayşe Tekel City and Regional Planning Dept., Gazi University Assist. Prof. Dr. Açalya Alpan Architecture Dept., Eskişehir Osmangazi University Date: 22.11.2019 I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Surname: Solmaz Zare Gharehgheshlaghi Signature: iv ABSTRACT PUBLIC ART IN PUBLIC SPACE: TRACKING GRAFFITI AND MURAL ART PRACTICES IN CONTEMPORARY TEHRAN Zare Gharehgheshlaghi, Solmaz Master Degree, Urban Design, Department of City and Regional Planning Supervisor: Prof. -

New Arab Art Order By: Khaled Ramadan

28 Essay New Arab Art Order By: Khaled Ramadan Hany Rashed, Forum Box, exhibtion space Helsinki 14. Background visual order in the region. Running in parallel with the Within the context of extreme political changes and increasing number of independent Arab image-makers, social instability, the Arab world has had to re-define one can observe the birth of alternative trends and the the landscape of its art and visual culture in response to visibility of true critical languages against the dominant its changing identity. discourse. These frontiers have developed a new visual The changes or rather the expansion of visual culture, language through the unconventional use of images, including the media industry, in the contemporary sounds and texts. The results are exciting, and so is the Arab world led to the birth of a new generation of freedom of expression and the audacity taken by the image-makers who are on the rise, offering alternative image-makers. In a way, due to their engagement and sources of information and entertainment, and persistence, this generation of image-makers can be enjoying increased social awareness from across the described as a resisting generation. It is not necessarily region. The new image-makers have managed to a politic resistance and far from an organized common expand our understanding of visually coming out of the movement. It is rather a colorful mosaic of individual Middle East as they seem to apply their own rules of statements, a diversification of point of views, a playful engagement which are shaping a new contemporary association of ideas. -

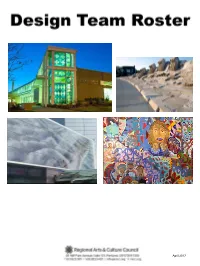

April 2017 Introduction

April 2017 Introduction The Regional Arts & Culture Council (RACC) established the Design Team Roster as an on-line resource that can be used by anyone seeking an artist for a project – community groups, business or property owners, schools, architecture firms, private developers or other public art programs. The Roster provides a pool of highly qualified artists, and increases the efficiency of the selection process. The intent of the roster is to provide users a range of artistic styles from which to select an artist that fits the needs of a particular project -- creating an art plan for a site; collaborating on early design along with having a budget to create artwork(s); identifying opportunities for other artists to provide design elements within the construction budget and/or complemented with public art funds; or, for creating a distinctive artwork for a site. These artist have demonstrated skills, experience and interest in commissioned projects. As you review this roster, please read the artists’ statement and view details of up to three past projects to get a feel for their work. You are strongly encouraged to visit the artists’ websites and social media outlets to further explore their practice. Please note that there are two different PDF versions you can view/download with the larger PDF containing artists’ resumes. Questions? Contact Public Art Managers: Kristin Calhoun [email protected] | 503.823.5101 Peggy Kendellen [email protected] | 503.823.4196 Cover artists clockwise from upper left: Anne Marie Karlsen, Lawndale, CA, 2008; Adam Kuby, Aberdeen, WA, 2013; Norie Sato, San Francisco, CA, 2011; Napoleon Jones-Henderson, Bruce C. -

Socially Engaged Art and Arts Education

BUILDING COMMUNITY: SOCIALLY ENGAGED ART AND ARTS EDUCATION ____________ A Project Presented To the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Interdisciplinary Master of Arts in Art Education: Pre-K – Older Adult ____________ by © Bobbie Rae Jones 2018 Spring 2018 BUILDING COMMUNITY: SOCIALLY ENGAGED ART AND ARTS EDUCATION A Project by Bobbie Rae Jones Spring 2018 APPROVED BY THE INTERIM DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES: Sharon Barrios, Ph.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: Carson D. Medley, Ed.D. Teresa L. Cotner, Ph.D., Chair Graduate Coordinator Jerome Pouwels, MFA PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this Project may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to the people that have supported me along the way. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to acknowledge the kind support from my mentor and friend Teresa Cotner, my guide into understanding my purpose, and to all those who supported and taught me the skills in arts I have learned along the way. v TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Publication Rights .............................................................................................................. iii Dedication ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................