THE DELAWARE V. the OSPREY. [2 Wall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sailing Skills & Seamanship

Sailing Skills & Seamanship - Course Description The U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary's Sailing Skills and Seamanship Course (SS&S) is a comprehensive course designed for both experienced and novice sailboat operators. The course, now in its 6 th edition that was published in 2008, is divided into parts: 10 core requirement two-to four-hour lessons plus 6 elective lessons that will enhance the skills required for a safe voyage in all conditions. These courses can be taught in addition to the core courses. TOPICS INCLUDE About Sailboats - Language of the sea; components of a sailboat; standing and running rigging; sails; types of sailboats; boat building materials; guidance on selecting and purchasing a boat. How A Boat Sails - Reading the wind; points of sailing, running, close hauled, reaching, sail shape; sail adjustments; when the wind picks up. Basic Sailboat Maneuvering - Tacking; jibbing; sailing a course; stability and angle of heel; knowing your boat. Rigging And Boat Handling - Stepping the mast; making sail; hoisting the sails; leaving the dock; mooring; controlling the sails; anchoring; weighing anchor. Equipment For Your Boat - Requirements for your boat; your boat's equipment; legal considerations. Trailering Your Sailboat - Legal considerations; practical considerations; selecting your trailer; the towing vehicle; handling your trailer; pre-departure checks; launching; retrieving; raising the mast; storing your boat and trailer; theft prevention; aquatic nuisance species; float plan. Your Highway Signs - Protection of ATONS; buoyage -

Event Information, Policies, and Agreements

Bow to Stern Boating Event Information, Policies, and Agreements This document includes: General Information, Policies, Procedures, Agreement Statements, and Waivers For the Following Events: Rental/Charter, ASA Certification/Lesson, Day Camp, and Other Program. Contact Bow to Stern if you have any questions concerning this information. Updated: March 18, 2021 Table of Contents General Information ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Registration ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 What to Bring ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Overnight Rentals/Charters/Lessons ............................................................................................................................ 4 Captain and Vessel Check-In/Out Procedures ........................................................................................................ 4 Captain Check-In ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 Captain Check-In Times ................................................................................................................................................. 4 -

Sea History$3.75 the Art, Literature, Adventure, Lore & Learning of the Sea

No. 109 NATIONAL MARITIME HISTORICAL SOCIETY WINTER 2004-2005 SEA HISTORY$3.75 THE ART, LITERATURE, ADVENTURE, LORE & LEARNING OF THE SEA THE AGE OF SAIL CONTINUES ON PICTON CASTLE Whaling Letters North Carolina Maritime Museum Rediscover the Colonial Periauger Sea History for Kids Carrying the Age of Sail Forward in the Barque Picton Castle by Captain Daniel D. Moreland oday the modern sailing school role of education, particularly maritime. ship is typically a sailing ship op- For example, in 1931 Denmark built the Terated by a charitable organization full-rigger Danmark as a merchant ma- whose mission is devoted to an academic rine school-ship which still sails in that or therapeutic program under sail, either role today. During this time, many other at sea or on coastwise passages. Her pro- maritime nations commissioned school gram uses the structure and environment ships for naval training as well, this time of the sailing ship to organize and lend without cargo and usually with significant themes to that structure and educational academic and often ambassadorial roles agenda. The goal, of course, being a fo- including most of the great classic sailing cused educational forum without neces- ships we see at tall ship events today. sarily being one of strictly maritime edu- These sailing ships became boot cation. Experiential education, leadership camps and colleges at sea. Those “trained training, personal growth, high school or in sail” were valued as problem solvers college credit, youth-at-risk, adjudicated and, perhaps more significantly, problem youth, science and oceanography as well preventers. They learned the wind and sea as professional maritime development are in a way not available to the denizens of often the focus of school ships. -

Sailing Course Materials Overview

SAILING COURSE MATERIALS OVERVIEW INTRODUCTION The NCSC has an unusual ownership arrangement -- almost unique in the USA. You sail a boat jointly owned by all members of the club. The club thus has an interest in how you sail. We don't want you to crack up our boats. The club is also concerned about your safety. We have a good reputation as competent, safe sailors. We don't want you to spoil that record. Before we started this training course we had many incidents. Some examples: Ran aground in New Jersey. Stuck in the mud. Another grounding; broke the tiller. Two boats collided under the bridge. One demasted. Boats often stalled in foul current, and had to be towed in. Since we started the course the number of incidents has been significantly reduced. SAILING COURSE ARRANGEMENT This is only an elementary course in sailing. There is much to learn. We give you enough so that you can sail safely near New Castle. Sailing instruction is also provided during the sailing season on Saturdays and Sundays without appointment and in the week by appointment. This instruction is done by skippers who have agreed to be available at these times to instruct any unkeyed member who desires instruction. CHECK-OUT PROCEDURE When you "check-out" we give you a key to the sail house, and you are then free to sail at any time. No reservation is needed. But you must know how to sail before you get that key. We start with a written examination, open book, that you take at home. -

Setting, Dousing and Furling Sails the Perception of Risk Is Very Important, Even Essential, to Organization the Sense of Adventure and the Success of Our Program

Setting, Dousing and Furling Sails The perception of risk is very important, even essential, to Organization the sense of adventure and the success of our program. The When at sea the organization for setting and assurance of safety is essential dousing sails will be determined by the Captain to the survival of our program and the First Mate. With a large and well- and organization. The trained crew, the crew may be able to be broken balancing of these seemingly into two groups, one for the foremast and one conflicting needs is one of the for the mainmast. With small crews, it will most difficult and demanding become necessary for everyone to know and tasks you will have in working work all of the lines anywhere on the ship. In with this program. any event, particularly if watches are being set, it becomes imperative that everyone have a good understanding of all lines and maneuvers the ship may be asked to perform. Safety Sailing the brigantines safely is our primary goal and the Los Angeles Maritime Institute has an enviable safety record. We should stress, however, that these ships are NOT rides at Disneyland. These are large and powerful sailing vessels and you can be injured, or even killed, if proper procedures are not followed in a safe, orderly, and controlled fashion. As a crewmember you have as much responsibility for the safe running of these vessels as any member of the crew, including the ship’s officers. 1. When laying aloft, crewmembers should always climb and descend on the weather side of the shrouds and the bowsprit. -

Racing Strategies for the South

Racing Strategies for the South Bay and Redwood Reach Appreciation to Sequoia Yacht Club Andrew Lesslie Racing Coordinator Spinnaker Sailing One-Design Fleet Let’s get to know each-other… Some icebreaker questions ● Do you sail with a chartplotter, ipad or portable GPS device? ● Do you have a steering compass? ● Does the boat you race carry a spinnaker? ● More than one spinnaker? ● Can you spell “asymmetric”? ● Do you have a polars for the boat you race? ● Is your sailmaker on speed dial? ● Does the boat you race draw more or less than 5’? ● Does the boat you race have a depth sounder? (one that works) ● How about a refrigerator? ● Can you see your jib tell-tales from your helming position? ● Does the boat you race rate more or less than 100? ● Have you argued about why your rating isn’t fair, ever? ● Do you know the magnetic bearing from S to Y? Strategy vs. Tactics? Strategy is the plan you make so you can sail the race course in the shortest possible time. Strategy is based on your boat and the sailing conditions. Tactics are the actions you take relative to other boats, so that you are free to follow your strategy. Your strategy is always your priority Your race is against the clock, especially when handicap racing The strategic process 1, 2, 3 Research the expected wind, current and sea state for the race area and the time of the race. Once we have the course, overlay our predictions on the course. What circumstances do we expect to see on each leg? Make a plan to sail the course in the shortest possible time, given the characteristics of our boat. -

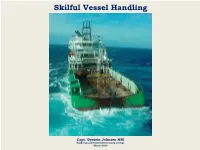

Skilful Vessel Handling

Skilful Vessel Handling Capt. Øystein Johnsen MNI Buskerud and Vestfold University College March 2014 Manoeuvring of vessels that are held back by an external force This consideration is written in belated wisdom according to the accident of Bourbon Dolphin in April 2007 When manoeuvring a vessel that are held back by an external force and makes little or no speed through the water, the propulsion propellers run up to the maximum, and the highest sideways force might be required against wind, waves and current. The vessel is held back by 1 800 meters of chain and wire, weight of 300 tons. 35 knops wind from SW, waves about 6 meter and 3 knops current heading NE has taken her 840 meters to the east (stb), out of the required line of bearing for the anchor. Bourbon Dolphin running her last anchor. The picture is taken 37 minutes before capsizing. The slip streams tells us that all thrusters are in use and the rudders are set to port. (Photo: Sean Dickson) 2 Lack of form stability I Emil Aall Dahle It is Aall Dahle’s opinion that the whole fleet of AHT/AHTS’s is a misconstruction because the vessels are based on the concept of a supplyship (PSV). The wide open after deck makes the vessels very vulnerable when tilted. When an ordinary vessel are listing an increasingly amount of volume of air filled hull is forced down into the water and create buoyancy – an up righting (rectification) force which counteract the list. Aall Dahle has a doctorate in marine hydrodynamics, has been senior principle engineer in NMD and DNV. -

Selene 45 Classic Explorer

Tel: +64 9 377 3328 Fax: +64 9 377 3325 info@yachtfindersglobal.co.nz Selene 45 Classic Explorer Description General The Selene 45 is an entirely new Next Year: 2022 Generation Selene. She is the smallest model of the popular and proven Selene Pilothouse Price: $1,254,732 Trawler line. Unlike her predecessor, the galley Additional Charges: None on the Selene 45 is offset to starboard providing Boat Type: Power a more spacious and accommodating salon. The pilothouse settee is L-shaped and also offset to Displacement Hull Type: starboard. There is room for a small helm chair Motoryacht www.yachtfindersglobal.co.nz in... Location: New Boat Engine/Fuel: Diesel Hull Material: GRP Dimensions Engines Length: 45 ft No. of Engines: 1 LOA: 14.76m Cummins or John Engine Brand: Deere Beam: 4.78m Engine(s) HP: 230 Draft: 1.59m Cruising Speed: 9 Knots Displacement: 62,830 lbs Max Speed: 10 Knots Builder / Designer Tankage Builder: Jet Tern Marine Fuel: 3785 Litres Designer: Howard Chen Water: 870 Litres Holding: Yes 1 2 Cook Gelcoat for hull, deck, superstructure & Manship S/S #316 opening portlights non-skid Manship S/S #316 hatches for pilothouse & fwd. Vinylester resin for the first 4 layers lamination stateroom Cymax bi-axis uni-direction stitched roving / mat Diamond/Sea-Glaze Dutch doors for pilothouse P&S, saloon entrance Taiwan Glass mat Taco S/S #316 solid upper & lower dual fender Divinycell core sandwich structure for hull side rails shell above the waterline & superstructure S/S #316 handrail for foredeck & dinghy deck Longitudinal stringers & transverse frames system S/S #316 telescope swim ladder 4 watertight bulkheads ( chain locker, fwd. -

After 88 Years - Four-Masted Barque PEKING Back in Her Homeport Hamburg

Four-masted barque PEKING - shifting Wewelfsfleth to Hamburg - September 2020 After 88 Years - Four-masted Barque PEKING Back In Her Homeport Hamburg Four-masted barque PEKING - shifting Wewelfsfleth to Hamburg - September 2020 On February 25, 1911 - 109 years ago - the four-masted barque PEKING was launched for the Hamburg ship- ping company F. Laeisz at the Blohm & Voss shipyard in Hamburg. The 115-metres long, and 14.40 metres wide cargo sailing ship had no engine, and was robustly constructed for transporting saltpetre from the Chilean coast to European ports. The ship owner’s tradition of naming their ships with words beginning with the letter “P”, as well as these ships’ regular fast voyages, had sailors all over the world call the Laeisz sailing ships “Flying P-Liners”. The PEKING is part of this legendary sailing ship fleet, together with a few other survivors, such as her sister ship PASSAT, the POMMERN and PADUA, the last of the once huge fleet which still is in active service as the sail training ship KRUZENSHTERN. Before she was sold to England in 1932 as stationary training ship and renamed ARETHUSA, the PEKING passed Cape Horn 34 times, which is respected among seafarers because of its often stormy weather. In 1975 the four-master, renamed PEKING, was sold to the USA to become a museum ship near the Brooklyn Bridge in Manhattan. There the old ship quietly rusted away until 2016 due to the lack of maintenance. -Af ter returning to Germany in very poor condition in 2017 with the dock ship COMBI DOCK III, the PEKING was meticulously restored in the Peters Shipyard in Wewelsfleth to the condition she was in as a cargo sailing ship at the end of the 1920s. -

CATBOAT GUIDE and SAILING MANUAL Collected from Web Sites, Articles, Manuals, and Forum Postings

CATBOAT GUIDE and SAILING MANUAL Collected from Web sites, articles, manuals, and forum postings Compiled and edited by: Edward Steinfeld [email protected] What I dream about. What fits my need best. ii Picnic cat by Com-Pac What I can trailer. Fisher Cat by Howard Boats iii Contents CATBOAT THESIS ...................................................................................................................1 MOORING AND DOCKING ...................................................................................................3 Docking ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Docking and Mooring ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Docking Lessons ...................................................................................................................................................................... 5 MENGER CAT 19 OWNER'S MANUAL ...............................................................................8 Stepping and Lowering the Tabernacle Mast ............................................................................................................... 8 Trailer Procedure ..................................................................................................................................................................... 9 Sailing -

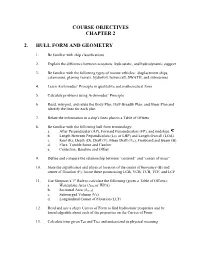

Course Objectives Chapter 2 2. Hull Form and Geometry

COURSE OBJECTIVES CHAPTER 2 2. HULL FORM AND GEOMETRY 1. Be familiar with ship classifications 2. Explain the difference between aerostatic, hydrostatic, and hydrodynamic support 3. Be familiar with the following types of marine vehicles: displacement ships, catamarans, planing vessels, hydrofoil, hovercraft, SWATH, and submarines 4. Learn Archimedes’ Principle in qualitative and mathematical form 5. Calculate problems using Archimedes’ Principle 6. Read, interpret, and relate the Body Plan, Half-Breadth Plan, and Sheer Plan and identify the lines for each plan 7. Relate the information in a ship's lines plan to a Table of Offsets 8. Be familiar with the following hull form terminology: a. After Perpendicular (AP), Forward Perpendiculars (FP), and midships, b. Length Between Perpendiculars (LPP or LBP) and Length Overall (LOA) c. Keel (K), Depth (D), Draft (T), Mean Draft (Tm), Freeboard and Beam (B) d. Flare, Tumble home and Camber e. Centerline, Baseline and Offset 9. Define and compare the relationship between “centroid” and “center of mass” 10. State the significance and physical location of the center of buoyancy (B) and center of flotation (F); locate these points using LCB, VCB, TCB, TCF, and LCF st 11. Use Simpson’s 1 Rule to calculate the following (given a Table of Offsets): a. Waterplane Area (Awp or WPA) b. Sectional Area (Asect) c. Submerged Volume (∇S) d. Longitudinal Center of Flotation (LCF) 12. Read and use a ship's Curves of Form to find hydrostatic properties and be knowledgeable about each of the properties on the Curves of Form 13. Calculate trim given Taft and Tfwd and understand its physical meaning i 2.1 Introduction to Ships and Naval Engineering Ships are the single most expensive product a nation produces for defense, commerce, research, or nearly any other function. -

Sail Power and Performance

the area of Ihe so-called "fore-triangle"), the overlapping part of headsail does not contribute to the driving force. This im plies that it does pay to have o large genoa only if the area of the fore-triangle (or 85 per cent of this area) is taken as the rated sail area. In other words, when compared on the basis of driving force produced per given area (to be paid for), theoverlapping genoas carried by racing yachts are not cost-effective although they are rating- effective in term of measurement rules (Ref. 1). In this respect, the rating rules have a more profound effect on the plan- form of sails thon aerodynamic require ments, or the wind in all its moods. As explicitly demonstrated in Fig. 2, no rig is superior over the whole range of heading angles. There are, however, con sistently poor performers such ns the La teen No. 3 rig, regardless of the course sailed relative to thewind. When reaching, this version of Lateen rig is inferior to the Lateen No. 1 by as rnuch as almost 50 per cent. To the surprise of many readers, perhaps, there are more efficient rigs than the Berntudan such as, for example. La teen No. 1 or Guuter, and this includes windward courses, where the Bermudon rig is widely believed to be outstanding. With the above data now available, it's possible to answer the practical question: how fast will a given hull sail on different headings when driven by eoch of these rigs? Results of a preliminary speed predic tion programme are given in Fig.