The Flight of Albatross—How to Transform It Into Aerodynamic Engineering?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wood-Stork-2005.Pdf

WOOD STORK Mycteria americana Photo of adult wood stork in landing posture and chicks in Close-up photo of adult wood stork. nest. Photo courtesy of USFWS/Photo by George Gentry Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. FAMILY: Ciconiidae STATUS: Endangered - U.S. Breeding Population (Federal Register, February 28, 1984) [Service Proposed for status upgrade to Threatened, December 26, 2013] DESCRIPTION: Wood storks are large, long-legged wading birds, about 45 inches tall, with a wingspan of 60 to 65 inches. The plumage is white except for black primaries and secondaries and a short black tail. The head and neck are largely unfeathered and dark gray in color. The bill is black, thick at the base, and slightly decurved. Immature birds have dingy gray feathers on their head and a yellowish bill. FEEDING HABITS: Small fish from 1 to 6 inches long, especially topminnows and sunfish, provide this bird's primary diet. Wood storks capture their prey by a specialized technique known as grope-feeding or tacto-location. Feeding often occurs in water 6 to 10 inches deep, where a stork probes with the bill partly open. When a fish touches the bill it quickly snaps shut. The average response time of this reflex is 25 milliseconds, making it one of the fastest reflexes known in vertebrates. Wood storks use thermals to soar as far as 80 miles from nesting to feeding areas. Since thermals do not form in early morning, wood storks may arrive at feeding areas later than other wading bird species such as herons. -

Colonial Nesting Waterbirds Fact Sheet

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Colonial-Nesting Waterbirds A Glorious and Gregarious Group What Is a Colonial-Nesting Waterbird? species of cormorants, gulls, and terns also Colonial-nesting waterbird is a tongue- occupy freshwater habitats. twister of a collective term used by bird biologists to refer to a large variety of Wading Birds seek their prey in fresh or different species that share two common brackish waters. As the name implies, characteristics: (1) they tend to gather in these birds feed principally by wading or large assemblages, called colonies, during standing still in the water, patiently waiting the nesting season, and (2) they obtain all for fish or other prey to swim within Migratory Bird Management or most of their food (fish and aquatic striking distance. The wading birds invertebrates) from the water. Colonial- include the bitterns, herons, egrets, night- nesting waterbirds can be further divided herons, ibises, spoonbills, and storks. Mission into two major groups depending on where they feed. Should We Be Concerned About the To conserve migratory bird Conservation Status of Colonial-Nesting populations and their habitats Seabirds (also called marine birds, oceanic Waterbirds? birds, or pelagic birds) feed primarily in Yes. While many species of seabirds for future generations, through saltwater. Some seabirds are so appear to have incredibly large careful monitoring and effective marvelously adapted to marine populations, they nevertheless face a management. environments that they spend virtually steady barrage of threats, such as oil their entire lives at sea, returning to land pollution associated with increased tanker only to nest; others (especially the gulls traffic and spills, direct mortality from and terns) are confined to the narrow entanglement and drowning in commercial coastal interface between land and sea, fishing gear, depletion of forage fishes due feeding during the day and loafing and to overexploitation by commercial roosting on land. -

Spread-Wing Postures and Their Possible Functions in the Ciconiidae

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY Von. 88 Oc:roBE'a 1971 No. 4 SPREAD-WING POSTURES AND THEIR POSSIBLE FUNCTIONS IN THE CICONIIDAE M. P. KAI-IL IN two recent papers Clark (19'69) and Curry-Lindahl (1970) have reported spread-wingpostures in storks and other birds and discussed someof the functionsthat they may serve. During recent field studies (1959-69) of all 17 speciesof storks, I have had opportunitiesto observespread-wing postures. in a number of speciesand under different environmentalconditions (Table i). The contextsin which thesepostures occur shed somelight on their possible functions. TYPES OF SPREAD-WING POSTURES Varying degreesof wing spreadingare shownby at least 13 species of storksunder different conditions.In somestorks (e.g. Ciconia nigra, Euxenuragaleata, Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis, and ]abiru mycteria) I observedno spread-wingpostures and have foundno referenceto them in the literature. In the White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) I observedonly a wing-droopingposture--with the wings held a short distanceaway from the sidesand the primaries fanned downward--in migrant birds wetted by a heavy rain at NgorongoroCrater, Tanzania. Other species often openedthe wingsonly part way, in a delta-wingposture (Frontis- piece), in which the forearmsare openedbut the primariesremain folded so that their tips crossin front o.f or below the. tail. In some species (e.g. Ibis leucocephalus)this was the most commonly observedspread- wing posture. All those specieslisted in Table i, with the exception of C. ciconia,at times adopted a full-spreadposture (Figures i, 2, 3), similar to those referred to by Clark (1969) and Curry-Lindahl (1970) in severalgroups of water birds. -

Imperiled Coastal Birds of Florida and the State Laws That Protect Them

Reddish Egret Roseate Spoonbill Threatened (S) Threatened (S) Imperiled Coastal The rarest heron in North Using spatulala-shaped Birds of Florida America, Reddish Egrets bills to feel prey in shallow are strictly coastal. They ponds, streams, or coastal and the chase small fish on open waters, Roseate Spoonbills State Laws that flats. They nest in small nest in trees along the numbers on estuary coast and inland. Having Protect Them islands, usually in colonies barely recovered from with other nesting wading hunting eradication, these birds. This mid-sized heron birds now face extirpation is mostly gray with rust- from climate change and colored head, though some sea-level rise. birds are solid white. Wood Stork Florida Sandhill Threatened (F) Florida Statutes and Rules Crane This large wading bird Threatened (S) is the only stork in the 68A-27.003 Designation and management of the state- This crane subspecies is Americas. Breeding areas listed species and coordination with federal government for resident year-round in have shifted from south federally-listed species Florida, and defends a Florida and the Everglades nesting territory that is northward. Wood Storks 68A-19.005 General Regulations relating to state- must have abundant prey adjacent to open upland designated Critical Wildlife Areas foraging habitat. Nesting concentrated in shallow in shallow ponds, adults wetlands in order to feed 68A-4.001 Controls harvest of wildlife only under permitted defend their eggs or chicks their young. Prey items from predators including include -

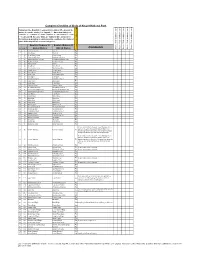

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

Flamingo Atlas

Flamingo Bulletin of the IUCN-SSC/Wetlands International FLAMINGO SPECIALIST GROUP Number 15, December 2007 ISSN 1680-1857 ABOUT THE GROUP The Flamingo Specialist Group (FSG) was established in 1978 at Tour du Valat in France, under the leadership of Dr. Alan Johnson, who coordinated the group until 2004. Currently, the group is coordinated from the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust at Slimbridge, UK, as part of the IUCN-SSC/Wetlands International Waterbird Network. The FSG is a global network of flamingo specialists (both scientists and non- scientists) involved in the study, monitoring, management and conservation of the world’s six flamingo species populations. Its role is to actively promote flamingo research and conservation worldwide by encouraging information exchange and cooperation among these specialists, and with other relevant organisations, particularly IUCN - SSC, Wetlands International, Ramsar, Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species, African Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement, and BirdLife International. FSG members include experts in both in-situ (wild) and ex-situ (captive) flamingo conservation, as well as in fields ranging from field surveys to breeding biology, infectious diseases, toxicology, movement tracking and data management. There are currently 208 members around the world, from India to Chile, and from Finland to South Africa. Further information about the FSG, its membership, the membership list serve, or this bulletin can be obtained from Brooks Childress at the address below. Chair Assistant Chair Dr. Brooks Childress Mr. Nigel Jarrett Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Slimbridge Slimbridge Glos. GL2 7BT, UK Glos. GL2 7BT, UK Tel: +44 (0)1453 860437 Tel: +44 (0)1453 891177 Fax: +44 (0)1453 860437 Fax: +44 (0)1453 890827 [email protected] [email protected] Eastern Hemisphere Chair Western Hemisphere Chair Dr. -

Supplementary Material

Ciconia ciconia (White Stork) European Red List of Birds Supplementary Material The European Union (EU27) Red List assessments were based principally on the official data reported by EU Member States to the European Commission under Article 12 of the Birds Directive in 2013-14. For the European Red List assessments, similar data were sourced from BirdLife Partners and other collaborating experts in other European countries and territories. For more information, see BirdLife International (2015). Contents Reported national population sizes and trends p. 2 Trend maps of reported national population data p. 4 Sources of reported national population data p. 6 Species factsheet bibliography p. 11 Recommended citation BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Further information http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/info/euroredlist http://www.birdlife.org/europe-and-central-asia/european-red-list-birds-0 http://www.iucnredlist.org/initiatives/europe http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/redlist/ Data requests and feedback To request access to these data in electronic format, provide new information, correct any errors or provide feedback, please email [email protected]. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds Ciconia ciconia (White Stork) Table 1. Reported national breeding population size and trends in Europe1. Country (or Population estimate Short-term population trend4 Long-term population trend4 Subspecific population (where relevant) 2 territory) Size (pairs)3 Europe (%) Year(s) Quality Direction5 Magnitude (%)6 Year(s) Quality Direction5 Magnitude (%)6 Year(s) Quality Albania 5-10 <1 2002-2012 good - 30-50 2002-2012 good - 70-80 1980-2012 poor Armenia 600-800 <1 2002-2012 good ? ? Austria 330-350 <1 2008-2012 good - 10-15 2001-2012 good 0 0 1980-2012 good C. -

Namibia Crane News 35

Namibia Crane News 35 March 2008 G O O D R AINS – AND FLO O D S – IN TH E NO R TH O F NAM IB IA News of the highest rainfalls in Caprivi and Kavango in 50 years; extensive floods in North Central; and good rains at Etosha and Bushmanland. Although the rains bring about exciting movements of birds, we also have sympathy with those whose lives and homes have been adversely affected by the floods. In this issue 1. Wattled Crane results from aerial survey in north- east Namibia … p1 2. Wattled Crane event book records from East Caprivi … p2 A pair of Wattled Cranes at Lake Ziwey, Ethiopia 3. Wattled Crane records from Bushmanland … p2 (Photo: Gunther Nowald, courtesy of ICF/EWT Partnership) 4. Floods in North Central … p3 5. Blue Crane news from Etosha … p3 Results & Discussion 6. Endangered bird survey in Kavango … p3 Eleven Wattled Cranes were recorded in the Mahango / 7. Why conserve wetlands? … p4 Buffalo area on the lower Kavango floodplains. In 2004 four cranes were seen in this area (Table 1). Twenty CAPR IVI & K AVANG O Wattled Cranes were recorded in the East Caprivi in 2007 (Figure 3; available on request), the same number as in 2004. Most (15) were seen in the Mamili National Park (eight in 2004), and five on the western side of the Kwandu in the Bwabwata National Park. No cranes were seen on the Linyanti-Chobe east of Mamili (eight S tatus of W attled Cranes on the flood- cranes seen in this stretch in 2004), and none on the plains of north-east Namibia: results from Zambezi and eastern floodplains. -

Kruger Comprehensive

Complete Checklist of birds of Kruger National Park Status key: R = Resident; S = present in summer; W = present in winter; E = erratic visitor; V = Vagrant; ? - Uncertain status; n = nomadic; c = common; f = fairly common; u = uncommon; r = rare; l = localised. NB. Because birds are highly mobile and prone to fluctuations depending on environmental conditions, the status of some birds may fall into several categories English (Roberts 7) English (Roberts 6) Comments Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps Date of Trip and base camps # Rob # Global Names Old SA Names Rough Status of Bird in KNP 1 1 Common Ostrich Ostrich Ru 2 8 Little Grebe Dabchick Ru 3 49 Great White Pelican White Pelican Eu 4 50 Pinkbacked Pelican Pinkbacked Pelican Er 5 55 Whitebreasted Cormorant Whitebreasted Cormorant Ru 6 58 Reed Cormorant Reed Cormorant Rc 7 60 African Darter Darter Rc 8 62 Grey Heron Grey Heron Rc 9 63 Blackheaded Heron Blackheaded Heron Ru 10 64 Goliath Heron Goliath Heron Rf 11 65 Purple Heron Purple Heron Ru 12 66 Great Egret Great White Egret Rc 13 67 Little Egret Little Egret Rf 14 68 Yellowbilled Egret Yellowbilled Egret Er 15 69 Black Heron Black Egret Er 16 71 Cattle Egret Cattle Egret Ru 17 72 Squacco Heron Squacco Heron Ru 18 74 Greenbacked Heron Greenbacked Heron Rc 19 76 Blackcrowned Night-Heron Blackcrowned Night Heron Ru 20 77 Whitebacked Night-Heron Whitebacked Night Heron Ru 21 78 Little Bittern Little Bittern Eu 22 79 Dwarf Bittern Dwarf Bittern Sr 23 81 Hamerkop -

Sussex White Stork Project Questions and Answers

Sussex White Stork Project Questions and Answers 1. How did the project start? Derek Gow and Coral Edgcumbe of the Derek Gow Consultancy undertook extensive research on the history of white storks in the UK which was published in British Wildlife. They subsequently produced a feasibility report with considerable input from Dr Roisin Campbell-Palmer and further commented on by various experts. Derek and colleagues approached Natural England, DEFRA and other interests in order to start the project. This initial work was funded by the Lund Fund. 2. Who is running the project? The project is a joint venture between a number of private landowners in Sussex and surrounding counties in partnership with Cotswold Wildlife Park and Derek Gow Consultancy. Birds for release are provided by Warsaw Zoo as well as other sites in Europe. Roy Dennis Wildlife Foundation is providing technical support. 3. Who is funding the project? The construction of pens and the husbandry and feeding of storks will be funded entirely by landowners themselves. The import and technical support costs are being funded by the Lund Fund, the grants programme launched by Peter Baldwin and Lisbet Rausing in 2016. All captive breeding and quarantine costs are funded by Cotswold Wildlife Park. 4. What is the long-term aim of the project The long term aim of the project is to restore a population of at least 50 breeding pairs of white storks in southern England. Central to this is the establishment of a breeding population in Sussex and surrounding counties that by 2030 is capable of producing sufficient juveniles to a level which is self-sustaining without the need for any further releases. -

Standard Abbreviations for Common Names of Birds M

Standard abbreviations for common names of birds M. Kathleen Klirnkiewicz I and Chandler $. I•obbins 2 During the past two decadesbanders have taken The system we proposefollows five simple rules their work more seriouslyand have begun record- for abbreviating: ing more and more informationregarding the birds they are banding. To facilitate orderly record- 1. If the commonname is a singleword, use the keeping,bird observatories(especially Manomet first four letters,e.g., Canvasback, CANV. and Point Reyes)have developedstandard record- 2. If the common name consistsof two words, use ing forms that are now available to banders.These the first two lettersof the firstword, followed by forms are convenientfor recordingbanding data the first two letters of the last word, e.g., manually, and they are designed to facilitate Common Loon, COLO. automateddata processing. 3. If the common name consists of three words Because errors in species codes are frequently (with or without hyphens),use the first letter of detectedduring editing of bandingschedules, the the first word, the first letter of the secondword, Bird BandingOffices feel that bandersshould use and the first two lettersof the third word, e.g., speciesnames or abbreviationsthereof rather than Pied-billed Grebe, PBGR. only the AOU or speciescode numbers on their field sheets.Thus, it is essentialthat any recording 4. If the common name consists of four words form have provision for either common names, (with or without hypens), use the first letter of Latin names, or a suitable abbreviation. Most each word, •.g., Great Black-backed Gull, recordingforms presentlyin use have a 4-digit GBBG.