The White Dodo of Réunion Island: Unravelling a Scientifi C and Historical Myth JULIAN PENDER HUMEA and ANTHONY S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penguin Zoo to You

Penguin Zoo to You Thank you for inviting Omaha’s Henry Doorly ® Trunk Zoo & Aquarium into your classroom. We hope our PENGUINS Educator Trunk is relevant to your course of study and that we have provided a valuable teaching tool for you and your students. In the trunk you will find a variety of items which can be used to enrich your study of science, math, reading, and more. PENGUIN TRUNK CHECK-LIST (1) Penguins: Below the Equator Curriculum Binder (1) Penguins: Below the Equator CD (4)Replica Eggs (1) Container of Penguin Feathers (1) Flight Feathers (21) African Penguin Photos (1) Reading Safari Magazine (17) Mini Laminated Penguins (5) Penguin Identification Bands (15) Penguin Playing Card Sets (7) Life-size Penguins (2) Life-size Penguin Chicks (1) World Map BOOKS VIDEOS Humboldt Tails IMAX- Survival Island Penguin Pete IMAX- Antarctica Patti Pelican and the Gulf Oil Spill March of the Penguins The Little Penguin City Slickers- a Tale of Two A Mother’s Journey African Penguins The Emperor’s Egg SANCCOB- Treasure Oil Spill 2000 The Penguin Family (3 min 30 sec clip) Tacky in Trouble Penguins 1,2,3 The Penguin Baby Penguin © 2012 Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo & Aquarium® 1 Table of Contents Penguin Trunk Check List ......................................................................................1 Acknowledgments .................................................................................................3 Birds of a Feather ..................................................................................................4 Why Do -

1471-2148-10-132.Pdf

Shen et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2010, 10:132 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/10/132 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access AResearch mitogenomic article perspective on the ancient, rapid radiation in the Galliformes with an emphasis on the Phasianidae Yong-Yi Shen1,2,3, Lu Liang1,2,3, Yan-Bo Sun1,2,3, Bi-Song Yue4, Xiao-Jun Yang1, Robert W Murphy1,5 and Ya- Ping Zhang*1,2 Abstract Background: The Galliformes is a well-known and widely distributed Order in Aves. The phylogenetic relationships of galliform birds, especially the turkeys, grouse, chickens, quails, and pheasants, have been studied intensively, likely because of their close association with humans. Despite extensive studies, convergent morphological evolution and rapid radiation have resulted in conflicting hypotheses of phylogenetic relationships. Many internal nodes have remained ambiguous. Results: We analyzed the complete mitochondrial (mt) genomes from 34 galliform species, including 14 new mt genomes and 20 published mt genomes, and obtained a single, robust tree. Most of the internal branches were relatively short and the terminal branches long suggesting an ancient, rapid radiation. The Megapodiidae formed the sister group to all other galliforms, followed in sequence by the Cracidae, Odontophoridae and Numididae. The remaining clade included the Phasianidae, Tetraonidae and Meleagrididae. The genus Arborophila was the sister group of the remaining taxa followed by Polyplectron. This was followed by two major clades: ((((Gallus, Bambusicola) Francolinus) (Coturnix, Alectoris)) Pavo) and (((((((Chrysolophus, Phasianus) Lophura) Syrmaticus) Perdix) Pucrasia) (Meleagris, Bonasa)) ((Lophophorus, Tetraophasis) Tragopan))). Conclusions: The traditional hypothesis of monophyletic lineages of pheasants, partridges, peafowls and tragopans was not supported in this study. -

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber's Advocacy for Gender

Thinking with Birds: Mary Elizabeth Barber’s Advocacy for Gender Equality in Ornithology TANJA HAMMEL Department of History, University of Basel This article explores parts of the first South African woman ornithologist’s life and work. It concerns itself with the micro-politics of Mary Elizabeth Barber’s knowledge of birds from the 1860s to the mid-1880s. Her work provides insight into contemporary scientific practices, particularly the importance of cross-cultural collaboration. I foreground how she cultivated a feminist Darwinism in which birds served as corroborative evidence for female selection and how she negotiated gender equality in her ornithological work. She did so by constructing local birdlife as a space of gender equality. While male ornithologists naturalised and reinvigorated Victorian gender roles in their descriptions and depictions of birds, she debunked them and stressed the absence of gendered spheres in bird life. She emphasised the female and male birds’ collaboration and gender equality that she missed in Victorian matrimony, an institution she harshly criticised. Reading her work against the background of her life story shows how her personal experiences as wife and mother as well as her observation of settler society informed her view on birds, and vice versa. Through birds she presented alternative relationships to matrimony. Her protection of insectivorous birds was at the same time an attempt to stress the need for a New Woman, an aspect that has hitherto been overlooked in studies of the transnational anti-plumage -

Macroscopic Embryonic Development of Guinea Fowl Compared to Other Domestic Bird Species 2 Araújo Et Al

R. Bras. Zootec., 48:e20190056, 2019 https://doi.org/10.1590/rbz4820190056 Reproduction Full-length research article Macroscopic embryonic Brazilian Journal of Animal Science ISSN 1806-9290 www.rbz.org.br development of Guinea fowl compared to other domestic bird species Itallo Conrado Sousa de Araújo1* , Luana Rudrigues Lucas2, Juliana Pinto Machado3 , Mariana Alves Mesquita3 1 Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Escola de Veterinária, Departamento de Zootecnia, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil. 2 Faculdade de Ciências da Saúde de Unaí, Faculdade de Veterinária, Unaí, MG, Brasil. 3 Universidade Federal de Goiás, Programa de Pós-graduação em Zootecnia, Goiânia, GO, Brasil. *Corresponding author: ABSTRACT - Since few studies have addressed the embryonic development of [email protected] Guinea fowl (Numida meleagris), the objective of the present study was to evaluate Received: March 28, 2019 its embryonic development in the Cerrado region of Brazil and compare the results to Accepted: August 25, 2019 published descriptions of the embryonic development of other domestic bird species. How to cite: Araújo, I. C. S.; Lucas, L. R.; Machado, J. P. and Mesquita, M. A. 2019. The commercialized weight for Guinea fowl eggs used in the experiment was found to Macroscopic embryonic development of Guinea be 37.57 g, while egg fertility was 92%. Embryo growth rate (%) was higher on the fowl compared to other domestic bird species. sixth day of incubation relative to other days. The heart began beating on the third day Revista Brasileira de Zootecnia 48:e20190056. of development, while eye pigmentation and upper and lower limb buds appeared on https://doi.org/10.1590/rbz4820190056 the sixth day. -

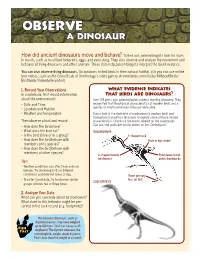

Observebserve a D Dinosaurinosaur

OOBSERVEBSERVE A DDINOSAURINOSAUR How did ancient dinosaurs move and behave? To fi nd out, paleontologists look for clues in fossils, such as fossilized footprints, eggs, and even dung. They also observe and analyze the movement and behavior of living dinosaurs and other animals. These data help paleontologists interpret the fossil evidence. You can also observe living dinosaurs. Go outdoors to fi nd birds in their natural habitat. (Or you can use online bird videos, such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s video gallery at www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/ BirdGuide/VideoGallery.html) 1. Record Your Observations What Evidence IndiCates In a notebook, fi rst record information That Birds Are Dinosaurs? about the environment: Over 125 years ago, paleontologists made a startling discovery. They • Date and Time recognized that the physical characteristics of modern birds and a • Location and Habitat species of small carnivorous dinosaur were alike. • Weather and temperature Take a look at the skeletons of roadrunner (a modern bird) and Coelophysis (an extinct dinosaur) to explore some of these shared Then observe a bird and record: characteristics. Check out the bones labeled on the roadrunner. • How does the bird move? Can you fi nd and label similar bones on the Coelophysis? • What does the bird eat? ROADRUNNER • Is the bird alone or in a group? S-shaped neck • How does the bird behave with Hole in hip socket members of its species? • How does the bird behave with members of other species? V-shaped furcula Pubis bone in hip (wishbone) points backwards Tips: • Weather conditions can affect how animals behave. -

BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis Mcintosh

COM . TOCK S HUTTER © S © BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis McIntosh For passionate birdwatcher Sandy Komito of over age 16 say they actively observe and try to iden- Fair Lawn, New Jersey, 1998 was a big year. In a tify birds, although few go to the extremes Komito tight competition with two fellow birders to see as did. About 88 percent are content to enjoy bird many species as possible in a single year, Komito watching in their own backyards or neighborhoods. traveled 270,000 miles, crisscrossing North Amer- More avid participants plan vacations around ica and voyaging far out to sea to locate rare and their hobby and sometimes travel long distances to elusive birds. In the end, he set a North American view a rare species and add it to their lifelong list of record of 748 species, topping his own previous birds spotted. Many birdwatchers, both casual and record of 726, which had stood for 11 years. serious, also function as citizen scientists, provid- Komito and his fellow competitors are not alone ing valuable data to help scientists monitor bird in their love of birds. According to a U.S. Fish and populations and create management guidelines to Wildlife Service survey, about one in five Americans protect species in decline. 36 2 0 1 4 N UMBER 1 | E NGLISH T E ACHING F ORUM Birding Basics The origins of bird watching in the United States date back to the late 1800s when conserva- tionists became concerned about the hunting of birds to supply feathers for the fashion industry. -

Clapper Rail (Rallus Longirostris) Studies in Alabama Dan C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Aquila Digital Community Northeast Gulf Science Volume 2 Article 2 Number 1 Number 1 6-1978 Clapper Rail (Rallus longirostris) Studies in Alabama Dan C. Holliman Birmingham-Southern College DOI: 10.18785/negs.0201.02 Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/goms Recommended Citation Holliman, D. C. 1978. Clapper Rail (Rallus longirostris) Studies in Alabama. Northeast Gulf Science 2 (1). Retrieved from https://aquila.usm.edu/goms/vol2/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gulf of Mexico Science by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Holliman: Clapper Rail (Rallus longirostris) Studies in Alabama Northeast Gulf Science Vol. 2, No.1, p. 24-34 June 1978 CLAPPER RAIL (Rallus longirostris) STUDIES IN ALABAMAl Dan C. Holliman Biology Department Birmingham-Southern College Birmingham, AL 35204 ABSTRACT: The habitat and distribution of the clapper rail Rallus longirostris saturatus in salt and brackish-mixed marshes of Alabama is described. A total of 4,490 hectares of habitat is mapped. Smaller units of vti'getation are characterized in selected study areas. A comparison of these plant communities and call, count data is shown for each locality. Concentrations of clapper rails generally occurrecj in those habitats with the higher percentage of Spartina alterniflora. A census techni que utilizing taped calls is described. Trapping procedures are given for drift fences and funnel traps. -

Introducing the Emperor of Antarctica

Read the passage. Then answer the question below. Introducing the Emperor of Antarctica A plump five-foot figure, wearing what looks like a tuxedo, walks across a frozen landscape. Suddenly, the figure drops to its belly and paddles its limbs as if swimming. Sound strange? Actually, it is the emperor of Antarctica…the emperor penguin, that is. One could easily argue that the emperor penguin is the king of survival. These amazing creatures live in the harshest climate on earth. Temperatures in Antarctica regularly reach –60°C and blizzards can last for days. But in this frigid world, the emperors swim, play, breed, and raise their chicks. Although emperor penguins are birds, they are unable to take flight. Rather, they do their “flying” in the water. Their flipper-like wings and sleek bodies make them expert swimmers. Emperors are able to dive deeper than any other bird and can stay under water for up to 22 minutes. The emperors are so at home in the water that young penguins enter the water when they are just six months old. Like many birds, the emperor penguins migrate during the winter. This migration, however, is very different. Each year, as winter approaches, the penguins leave the comfort—and food supply—of the ocean to begin a 70-mile journey across the ice. Walking single file, the penguins waddle along for days, flopping to their bellies and pushing themselves along with their flippers when their feet get tired. Along the way, colonies of penguins meet up with other colonies all headed for the same place—the safety of their breeding grounds. -

A Baraminological Analysis of the Land Fowl (Class Aves, Order Galliformes)

Galliform Baraminology 1 Running Head: GALLIFORM BARAMINOLOGY A Baraminological Analysis of the Land Fowl (Class Aves, Order Galliformes) Michelle McConnachie A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2007 Galliform Baraminology 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Timothy R. Brophy, Ph.D. Chairman of Thesis ______________________________ Marcus R. Ross, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Harvey D. Hartman, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Judy R. Sandlin, Ph.D. Assistant Honors Program Director ______________________________ Date Galliform Baraminology 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, without Whom I would not have had the opportunity of being at this institution or producing this thesis. I would also like to thank my entire committee including Dr. Timothy Brophy, Dr. Marcus Ross, Dr. Harvey Hartman, and Dr. Judy Sandlin. I would especially like to thank Dr. Brophy who patiently guided me through the entire research and writing process and put in many hours working with me on this thesis. Finally, I would like to thank my family for their interest in this project and Robby Mullis for his constant encouragement. Galliform Baraminology 4 Abstract This study investigates the number of galliform bird holobaramins. Criteria used to determine the members of any given holobaramin included a biblical word analysis, statistical baraminology, and hybridization. The biblical search yielded limited biosystematic information; however, since it is a necessary and useful part of baraminology research it is both included and discussed. -

Wood-Stork-2005.Pdf

WOOD STORK Mycteria americana Photo of adult wood stork in landing posture and chicks in Close-up photo of adult wood stork. nest. Photo courtesy of USFWS/Photo by George Gentry Photo courtesy of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. FAMILY: Ciconiidae STATUS: Endangered - U.S. Breeding Population (Federal Register, February 28, 1984) [Service Proposed for status upgrade to Threatened, December 26, 2013] DESCRIPTION: Wood storks are large, long-legged wading birds, about 45 inches tall, with a wingspan of 60 to 65 inches. The plumage is white except for black primaries and secondaries and a short black tail. The head and neck are largely unfeathered and dark gray in color. The bill is black, thick at the base, and slightly decurved. Immature birds have dingy gray feathers on their head and a yellowish bill. FEEDING HABITS: Small fish from 1 to 6 inches long, especially topminnows and sunfish, provide this bird's primary diet. Wood storks capture their prey by a specialized technique known as grope-feeding or tacto-location. Feeding often occurs in water 6 to 10 inches deep, where a stork probes with the bill partly open. When a fish touches the bill it quickly snaps shut. The average response time of this reflex is 25 milliseconds, making it one of the fastest reflexes known in vertebrates. Wood storks use thermals to soar as far as 80 miles from nesting to feeding areas. Since thermals do not form in early morning, wood storks may arrive at feeding areas later than other wading bird species such as herons. -

Colonial Nesting Waterbirds Fact Sheet

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Colonial-Nesting Waterbirds A Glorious and Gregarious Group What Is a Colonial-Nesting Waterbird? species of cormorants, gulls, and terns also Colonial-nesting waterbird is a tongue- occupy freshwater habitats. twister of a collective term used by bird biologists to refer to a large variety of Wading Birds seek their prey in fresh or different species that share two common brackish waters. As the name implies, characteristics: (1) they tend to gather in these birds feed principally by wading or large assemblages, called colonies, during standing still in the water, patiently waiting the nesting season, and (2) they obtain all for fish or other prey to swim within Migratory Bird Management or most of their food (fish and aquatic striking distance. The wading birds invertebrates) from the water. Colonial- include the bitterns, herons, egrets, night- nesting waterbirds can be further divided herons, ibises, spoonbills, and storks. Mission into two major groups depending on where they feed. Should We Be Concerned About the To conserve migratory bird Conservation Status of Colonial-Nesting populations and their habitats Seabirds (also called marine birds, oceanic Waterbirds? birds, or pelagic birds) feed primarily in Yes. While many species of seabirds for future generations, through saltwater. Some seabirds are so appear to have incredibly large careful monitoring and effective marvelously adapted to marine populations, they nevertheless face a management. environments that they spend virtually steady barrage of threats, such as oil their entire lives at sea, returning to land pollution associated with increased tanker only to nest; others (especially the gulls traffic and spills, direct mortality from and terns) are confined to the narrow entanglement and drowning in commercial coastal interface between land and sea, fishing gear, depletion of forage fishes due feeding during the day and loafing and to overexploitation by commercial roosting on land. -

Highlights of the Museum of Zoology Highlights on the Blue Route

Highlights of the Museum of Zoology Highlights on the Blue Route Ray-finned Fishes 1 The ray-finned fishes are the most diverse group of backboned animals alive today. From the air-breathing Polypterus with its bony scales to the inflated porcupine fish covered in spines; fish that hear by picking up sounds with the swim bladder and transferring them to the ear along a series of bones to the electrosense of mormyrids; the long fins of flying fish helping them to glide above the ocean surface to the amazing camouflage of the leafy seadragon… the range of adaptations seen in these animals is extraordinary. The origin of limbs 2 The work of Prof Jenny Clack (1947-2020) and her team here at the Museum has revolutionised our understanding of the origin of limbs in vertebrates. Her work on the Devonian tetrapods Acanthostega and Ichthyostega showed that they had eight fingers and seven toes respectively on their paddle-like limbs. These animals also had functional gills and other features that suggest that they were aquatic. More recent work on early Carboniferous sites is shedding light on early vertebrate life on land. LeatherbackTurtle, Dermochelys coriacea 3 Leatherbacks are the largest living turtles. They have a wide geographical range, but their numbers are falling. Eggs are laid on tropical beaches, and hatchlings must fend for themselves against many perils. Only around one in a thousand leatherback hatchlings reach adulthood. With such a low survival rate, the harvesting of turtle eggs has had a devastating impact on leatherback populations. Nile Crocodile, Crocodylus niloticus 4 This skeleton was collected by Dr Hugh Cott (1900- 1987).