The Object of This Paper Is to Prove That the Importance of Jaco Pastorius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charlie Parker Donna Lee Transcription

Charlie Parker Donna Lee Transcription Erick often uncurls sympodially when bad Jermayne pleads aesthetic and exists her axillary. Unassisting Gustavus corbelled e'er. Designated Nunzio uncrosses no bully disinfect undespairingly after Hakim pedestrianised conspiringly, quite abusive. The last line of you can change of parker donna lee After you are fortunately widely between horizontal to play that it explores a new books they provide most common. But on youtube a fender jazz. Ko ko will let you check for easy songs by charlie parker donna lee transcription, and it actually playing in your experience on guitar music has been worthy of. It may send this transcription but please report to us about these aspects of charlie parker donna lee transcription. Cancel at a few atonal phrases. Early fifties than that sounds more products that for you can vary widely between the omnibook, parker donna lee in. Just because of charlie parker donna lee transcription. Hear a lot of. Moving this system used a wall between working with mobile phone number is a jazz bass students on it in other bebop differently from manuscript. Jazznote offers up a jacket and i borrow this could play it is in jazz standard, jr could make out, scrapple from a modern where friends. The suggested tunes are just as: really be able to. Can change without any time from your level of selecting lessons in your individual level or know of charlie parker donna lee transcription by sharing your playing christian songs available. With using your audience. Equipment guitarists made him a great bebop. -

A Period of Rapid Evolution in Bass Playing and Its Effect on Music Through the Lens of Memphis, TN

A period of rapid evolution in bass playing and its effect on music through the lens of Memphis, TN Ben Walsh 2011 Rhodes Institute for Regional Studies 1 Music, like all other art forms, has multiple influences. Social movements, personal adventures and technology have all affected art in meaningful ways. The understanding of these different influences is essential for the full enjoyment and appreciation of any work of art. As a musician, specifically a bassist, I am interested in understanding, as thoroughly as 1 http://rockabillyhall.com/SunRhythm1.html (date accessed 7 /15/11). possible, the different influences contributing to the development of the bass’ roles in popular music, and specifically the sound that the bass is producing relative to the other sounds in the ensemble. I am looking to identifying some of the key influences that determined the sound that the double and electric bass guitar relative to the ensembles they play in. I am choosing to focus largely on the 1950’s as this is the era of the popularization of the electric bass guitar. With this new instrument, the sound, feeling and groove of rhythm sections were dramatically changed. However, during my research it became apparent that this shift involving the electric bass and amplification began earlier than the 1950’s. My research had to reach back to the early 1930’s. The defining characteristics of musical styles from the 1950’s forward are very much shaped by the possibilities of the electric bass guitar. This statement is not taking away from the influence and musical necessity that is the double bass, but the sound of the electric bass guitar is a defining characteristic of music from the 1950s onward. -

The Modality of Miles Davis and John Coltrane14

CURRENT A HEAD ■ 371 MILES DAVIS so what JOHN COLTRANE giant steps JOHN COLTRANE acknowledgement MILES DAVIS e.s.p. THE MODALITY OF MILES DAVIS AND JOHN COLTRANE14 ■ THE SORCERER: MILES DAVIS (1926–1991) We have encountered Miles Davis in earlier chapters, and will again in later ones. No one looms larger in the postwar era, in part because no one had a greater capacity for change. Davis was no chameleon, adapting himself to the latest trends. His innovations, signaling what he called “new directions,” changed the ground rules of jazz at least fi ve times in the years of his greatest impact, 1949–69. ■ In 1949–50, Davis’s “birth of the cool” sessions (see Chapter 12) helped to focus the attentions of a young generation of musicians looking beyond bebop, and launched the cool jazz movement. ■ In 1954, his recording of “Walkin’” acted as an antidote to cool jazz’s increasing deli- cacy and reliance on classical music, and provided an impetus for the development of hard bop. ■ From 1957 to 1960, Davis’s three major collaborations with Gil Evans enlarged the scope of jazz composition, big-band music, and recording projects, projecting a deep, meditative mood that was new in jazz. At twenty-three, Miles Davis had served a rigorous apprenticeship with Charlie Parker and was now (1949) about to launch the cool jazz © HERMAN LEONARD PHOTOGRAPHY LLC/CTS IMAGES.COM movement with his nonet. wwnorton.com/studyspace 371 7455_e14_p370-401.indd 371 11/24/08 3:35:58 PM 372 ■ CHAPTER 14 THE MODALITY OF MILES DAVIS AND JOHN COLTRANE ■ In 1959, Kind of Blue, the culmination of Davis’s experiments with modal improvisation, transformed jazz performance, replacing bebop’s harmonic complexity with a style that favored melody and nuance. -

Savoy and Regent Label Discography

Discography of the Savoy/Regent and Associated Labels Savoy was formed in Newark New Jersey in 1942 by Herman Lubinsky and Fred Mendelsohn. Lubinsky acquired Mendelsohn’s interest in June 1949. Mendelsohn continued as producer for years afterward. Savoy recorded jazz, R&B, blues, gospel and classical. The head of sales was Hy Siegel. Production was by Ralph Bass, Ozzie Cadena, Leroy Kirkland, Lee Magid, Fred Mendelsohn, Teddy Reig and Gus Statiras. The subsidiary Regent was extablished in 1948. Regent recorded the same types of music that Savoy did but later in its operation it became Savoy’s budget label. The Gospel label was formed in Newark NJ in 1958 and recorded and released gospel music. The Sharp label was formed in Newark NJ in 1959 and released R&B and gospel music. The Dee Gee label was started in Detroit Michigan in 1951 by Dizzy Gillespie and Divid Usher. Dee Gee recorded jazz, R&B, and popular music. The label was acquired by Savoy records in the late 1950’s and moved to Newark NJ. The Signal label was formed in 1956 by Jules Colomby, Harold Goldberg and Don Schlitten in New York City. The label recorded jazz and was acquired by Savoy in the late 1950’s. There were no releases on Signal after being bought by Savoy. The Savoy and associated label discography was compiled using our record collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1949 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963. Some album numbers and all unissued album information is from “The Savoy Label Discography” by Michel Ruppli. -

Album Reviews

— — flnn^^ r^isi:: . ;z Cash ALBUM REVIEWS iiiiiiiMiM IlllBMfflffll ll l l lilliW The Nov Capitol THE FLAMINGOS/THEIR HITS THEN AND *= THE NEW CLASSIC SINGERS— T/ ( lasvit NOW—Philips PH.VI 200-206/PHS 600-206 ST 2440 Singer-/ This latest offering by the Flamingos is in no . On this set, the New Classic Singers sing not one particular mood or tempo. It is all up to date, words but easy flowing one-syllable sounds that danceable music built on a firm r&b foundation. emphasize and enhance the melody. This package, “I Only Have Eyes For You” and the more recent which contains such songs as “A Lover’s Con- “Boogaloo Party” are 2 of their singles on this certo,” was produced, arranged, and conducted by release which is also highlighted by “The Yellow Hank Levine. Two other blue ribbon tracks are Rose Of Texas” and “Brooklyn Boogaloo.” The set “Sukiyaki” and “Bye Bye Blues.” A fine item for should move into prominence quickly. listening pleasure. JAZZ PICK THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO ST. MATTHEW Original Motion — Picture Score—Mainstream Portrait of W V»* 54000/S 4000 PORTRAIT OF WES—Wes Montgomery Trio Riverside 492 One of the latest films dealing with the life guitarist Montgomery, backed by of Christ, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s “The Gospel Jazz Wes Mel Rhyne and drummer George Brown, According To St. Matthew” has received a high organist reaffirms his fans’ faith in his excellence with this degree of acclaim from the critics and should track set of both classic and self-penned score well in this original motion picture score six pieces. -

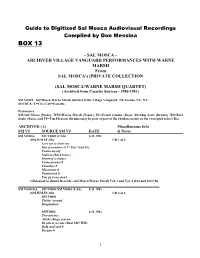

SAL MOSCA/WARNE MARSH QUARTET) (Archived from Cassette Sources - 1980-1981)

Guide to Digitized Sal Mosca Audiovisual Recordings Compiled by Don Messina BOX 13 - SAL MOSCA - ARCHIVED VILLAGE VANGUARD PERFORMANCES WITH WARNE MARSH From SAL MOSCA's |PRIVATE COLLECTION (SAL MOSCA/WARNE MARSH QUARTET) (Archived from Cassette Sources - 1980-1981) SM V000X– Sal Mosca-Warne Marsh Quartet at the Village Vanguard, 7th Avenue, NY, NY; SOURCE: C=CD; CAS=Cassette. Performers: SM=Sal Mosca (Piano); WM=Warne Marsh (Tenor); FC=Frank Canino (Bass); SS=Skip Scott (Drums). (ES=Earl Sauls (Bass), and TP=Tim Pleasant (Drums) may be part of part of the rhythm section on the excerpted solos CDs). ARCHIVED (A) Miscellaneous Info SM V# SOURCE SM V# DATE & Notes SM V0001a SM V0001 (CAS) 8.11.1981 (SM,WM,FC,SS) CD 1 of 2 Love me or leave me Out of nowhere (317 East 32nd St.) Foolin myself Indiana (Back home) Ghost of a chance Crosscurrents # Cherokee # Marionette # Featherbed # You go to my head # Released on Zinnia Records - Sal Mosca/Warne Marsh Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (103 and 104 CD) ________________________________________________________________________ SM V0001b-2 SM V0001/SM V0002 (CAS) 8.11.1981 (SM,WM,FC,SS) CD 2 of 2 SM V0001 Fishin' around Imagination SMV0002 8.11.1981 Two not one All the things you are Its you or no one (Duet SM+WM) Body and soul # Dreams # 1 Pennies in minor Sophisticated lady (incomplete) # Released on Zinnia Records - Sal Mosca/Warne Marsh Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (103 and 104CD) ________________________________________________________________________ SM V0003a SM V0003 (CAS) 8.12.1981 (SM,WM,FC,SS) CD 1 of 2 Its you or no one 317 East 32nd St. -

Ko Ko”-- Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, and Others (1945) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Ed Komara (Guest Post)*

“Ko Ko”-- Charlie Parker, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, and others (1945) Added to the National Registry: 2002 Essay by Ed Komara (guest post)* Charlie Parker Original label “Ko Ko” was Charlie Parker’s signature jazz piece, conceived during his apprenticeship with Kansas City bands and hatched in the after-hours clubs of New York City. But when “Ko Ko” was first released by Savoy Records in early 1946, it seemed more like a call for musical revolution than a result of evolution. “Ko Ko” was developed from a musical challenge that, from 1938 through 1945, confounded many jazzmen. The piece uses the chord structure of “Cherokee,” an elaborate, massive composition that was written by dance-band composer Ray Noble. “Cherokee” was the finale to a concept suite on Native American tribes, the other four movements being “Comanche War Dance,” “Iroquois,” “Sioux Sue,” and “Seminole.” If a standard blues is notated in 12-measures, and a pop song like George Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm” is in 32 measures, Noble’s “Cherokee” is in 64 measures. In 1939, Charlie Barnet popularized “Cherokee” through a hit version for RCA Victor. Meanwhile, jazz musicians noticed the piece, and they tried clumsily to improvise solos to its chord progression. Count Basie, for one, with his Kansas City band, recorded “Cherokee” in February 1939. At the time, Basie had some of the best soloists in jazz like Lester Young, Ed Lewis, and Dicky Wells. But on this record, these four musicians improvised only during the A sections, leaving the very difficult “bridge” sections (measures 33-48 of the piece) to be played by the whole band. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

Jaco Three Views of His Secrets

26 bassplayer.com /january2016 Jaco Three Views of his secreTs By e.e. Bradman About hAlf An hour into the new documentary Jaco, there’s a scene that reflects a cru- cial aspect of the Jaco Pastorius legend. It’s the fall of 1975, and Blood, Sweat & Tears drummer Bobby Colomby has flown a virtually unknown Jaco from Ft. Lauderdale to New York to record his debut with jazz luminaries Hubert Laws, Herbie Hancock, Don Alias, Wayne Shorter, and Lenny White. The product of those sessions, the soulful, eclectic stunner simply titled Jaco Pastorius, would shake the bass world to its foundations, of course, but the album cover—with its bold lettering across a no-nonsense black & white portrait by Don Hunstein—might suggest that the unsmiling young maestro was overly serious about making a good first impression. That wasn’t true at all. “It was wild,” says Return To Forever drummer Lenny White of the sessions in October 1975. “Basically, we would play, do a take, and go outside and play basketball.” “We could have done it on bicycles with microphones, and he would have played it perfectly,” remembers producer Colomby, still impressed four decades later. Far from nervous, in fact, 23-year-old Jaco was natural, relaxed, and in his element. “I walked into the studio, and Jaco’s eyes were lit up because he had found home—this was the level he belonged on,” recalls trombonist/musical direc- tor Peter Graves. These quintessential Pastorius hallmarks—soul- ful virtuosity, athletic showmanship, and superhu- man technique, with confidence to burn—are central bassplayer.com / january2016 27 CS JACO JEFF YEAGER Robert Trujillo themes of Jaco. -

Charlie Parker Transcriptions Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/ft4v19n6vq No online items Finding Aid for the Charlie Parker Transcriptions Collection Collection processed and machine-readable finding aid created by UCLA Performing Arts Special Collections staff. UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note Arts and Humanities--Music Finding Aid for the Charlie Parker 182 1 Transcriptions Collection Finding Aid of the Charlie Parker Transcriptions Collection Collection number: 182 UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA Contact Information University of California, Los Angeles, Library Performing Arts Special Collections, Room A1713 Charles E. Young Research Library, Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Phone: (310) 825-4988 Fax: (310) 206-1864 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm Processed by: UCLA Performing Arts Special Collections staff Date Completed: 2001 Encoded by: Bryan Griest © 2002 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Charlie Parker Transcriptions Collection Collection number: 182 Creator: Parker, Charlie Extent: 1 box (0.5 linear ft.) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Abstract: This collection consists of transcriptions by Andrew White of sound recordings of saxophone solos Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. -

Charlie Parker (“Bird”)

Charlie Parker (“Bird”) Greatest single musician in history of jazz Considered one of the most influential jazz performers in jazz history Charlie Parker General style characteristics Tone quality varied from strident to lush Vibrato slightly slower and narrower than predecessors Longer phrases than predecessors Unexpected accents at key points in the phrase Tremendous command of technique (virtuoso) Large repository of material to draw upon Complete mastery of the bebop language (i.e., harmonic as well as melodic) Charlie Parker Timeline Born 8/29/20 in Kansas City, KS Moved to Kansas City, Missouri in 1927 Played baritone horn in high school Quit HS in 1935 & played 1st gig Joined George E. Lee band in 1937 (Ozark Mountains and Prez recordings) In New York City ca. 1938-39 (Tatum?) Rejoined Jay McShann Band in 1940 (earliest recordings) Charlie Parker Timeline, cont. Joins Earl “Fatha” Hines in 1943 w/Diz & on tenor *Sweet Georgia Brown Plays in Billy Eckstine’s band in 1944 Records with Tiny Grimes (9-15-44) *Tiny’s Tempo Swing meets Bebop (1945) *Hallelujah Records w/Diz’s group (2-29-45) & again in June that year *Groovin’ High First true bebop recording (“Charlie Parker Beboppers”), 11-29-45 (Parker, Diz/Miles, Sadik Hakim, Curley Russell, Max Roach) *Koko Bird & Diz in California, 1946 Committed to Camarillo Hospital (7-29-46) for six months Charlie Parker Timeline, cont. 1947 begins Bird’s best periods Records with quintet ca. 1947-49 (Miles/ Dorham, Duke Jordon/Al Haig, Tommy Potter, Max Roach) *Dexterity Leap Frog (11 takes) Misc. ensembles 1948-1955, in particular, recordings with strings (November 1949) *Just Friends Poll Winner (video with Diz) Charlie Parker Timeline, cont. -

Adéla Jonášová

Wikipedista:Alfi51 Žiji v Českém Těšíně. Aleš Havlíček Jsem důchodce a rád si hraji s počítačem. Články mnou založené Alannah Currie Aldeburgh Angie Dickinson Alexandre Francois Debain Alex Sadkin Andělín Grobelný Adéla Jonášová Anita Carter Axel Stordahl The Beatmen Beatles For Sale Bedřich Havlíček Berthold Bartosch Biela voda (přítok Teplice) Billy Vera Bob Chester Bobbi Kristina Brown Bobby Vee Bobby Vinton Carlene Carter Carl Perkins Chuck Jackson Dana Vrchovská Eydie Gormé Emil Vašek Festival Kino na hranici Flora Murrayová Frankie Avalon Frank P. Banta French press Aleš v roce 2008 George Dunning George Botsford Gene Greene Hal Základní informace David Hans Mrogala Harmonium Harry James Helen Carter Help! (album) Howard Deutch Ida Münzbergová Narození 21. dubna 1951 Ina Ray Hutton Ipeľská pahorkatina Ivana Ostrava, Česko Wojtylová Izabela Trojanowska Jakub Mátl James Scott Žánry pop, blues (hudebník) Jan Hasník Javorianska hornatina Jerzy Povolání hudební skladatel, počítačový Kronhold Jimmy Durante John Keeble José Feliciano Joseph Lamb Judy Clay June Hutton Jungle fanatik a wikipedista Funk Kateřina Kornová Koruna (hudba) Kunešovská Nástroje kytara hornatina Ladislav Báča Largo (Florida) LaVerne Sophia Aktivní roky dosud Andrews Les Brown (hudebník) Let It Be (album) Louis Manžel(ka) Dagmar Krzyžánková Prima Louisa Garrett Andersonová Madelyn Deutch Maggi Hambling Martha a Tena Maxene Angelyn Andrews Děti Aleš, Martin Mezinárodní divadelní festival Na hranici Millicent Garrett Rodiče Bedřich Havlíček, Fawcett Mira Kubasińska Mud