Treaty of Lausanne: the Tool of Minority Protection for the Cham Albanians of Greece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chameria History - Geographical Space and Albanian Time’

Conference Chameria Issue: International Perspectives and Insights for a Peaceful Resolution Kean University New Jersey USA Saturday, November 12th, 2011 Paper by Professor James Pettifer (Oxford, UK) ‘CHAMERIA HISTORY - GEOGRAPHICAL SPACE AND ALBANIAN TIME’ ‘For more than two centuries, the Ottoman Empire, once so formidable was gradually sinking into a state of decrepitude. Unsuccessful wars, and, in a still greater degree, misgovernment and internal commotions were the causes of its decline.’ - Richard Alfred Davenport,’ The Life of Ali Pasha Tepelena, Vizier of Epirus’i. On the wall in front of us is a map of north-west Greece that was made by a French military geographer, Lapie, and published in Paris in 1821, although it was probably in use in the French navy for some years before that. Lapie was at the forefront of technical innovation in cartography in his time, and had studied in Switzerland, the most advanced country for cartographic science in the late eighteenth century. It is likely that it was made for military use in the Napoleonic period wars against the British. Its very existence is a product of British- French national rivalry in the Adriatic in that period. Modern cartography had many of its roots in the Napoleonic Wars period and immediately before in the Eastern Mediterranean, when intense naval competition between the British and French for control of these waters led to major scientific advances. In turn, in the eighteenth century, similar progress had been made in both countries as a result of earlier wars in the Atlantic. This map is titled ‘Chameria/Thesprotia’, and so at that time it is clear that the two traditional names for the region, Albanian and Greek, were both in common use then, not only locally but by the often classically-educated officers of a European Great Power. -

The United Nations' Political Aversion to the European Microstates

UN-WELCOME: The United Nations’ Political Aversion to the European Microstates -- A Thesis -- Submitted to the University of Michigan, in partial fulfillment for the degree of HONORS BACHELOR OF ARTS Department Of Political Science Stephen R. Snyder MARCH 2010 “Elephants… hate the mouse worst of living creatures, and if they see one merely touch the fodder placed in their stall they refuse it with disgust.” -Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, 77 AD Acknowledgments Though only one name can appear on the author’s line, there are many people whose support and help made this thesis possible and without whom, I would be nowhere. First, I must thank my family. As a child, my mother and father would try to stump me with a difficult math and geography question before tucking me into bed each night (and a few times they succeeded!). Thank you for giving birth to my fascination in all things international. Without you, none of this would have been possible. Second, I must thank a set of distinguished professors. Professor Mika LaVaque-Manty, thank you for giving me a chance to prove myself, even though I was a sophomore and studying abroad did not fit with the traditional path of thesis writers; thank you again for encouraging us all to think outside the box. My adviser, Professor Jenna Bednar, thank you for your enthusiastic interest in my thesis and having the vision to see what needed to be accentuated to pull a strong thesis out from the weeds. Professor Andrei Markovits, thank you for your commitment to your students’ work; I still believe in those words of the Moroccan scholar and will always appreciate your frank advice. -

San Marino Legal E

Study on Homophobia, Transphobia and Discrimination on Grounds of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Legal Report: San Marino 1 Disclaimer: This report was drafted by independent experts and is published for information purposes only. Any views or opinions expressed in the report are those of the author and do not represent or engage the Council of Europe or the Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights. 1 This report is based on Dr Maria Gabriella Francioni, The legal and social situation concerning homophobia and discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in the Republic of San Marino , University of the Republic of San Marino, Juridical Studies Department, 2010. The latter report is attached to this report. Table of Contents A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 B. FINDINGS 3 B.1. Overall legal framework 3 B.2. Freedom of Assembly, Association and Expression 10 B.3. Hate crime - hate speech 10 B.4. Family issues 13 B.5. Asylum and subsidiary protection 16 B.6. Education 17 B.7. Employment 18 B.8. Health 20 B.9. Housing and Access to goods and services 21 B.10. Media 22 B.11. Transgender issues 23 Annex 1: List of relevant national laws 27 Annex 2: Report of Dr Maria Gabriella Francioni, The legal and social situation concerning homophobia and discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in the Republic of San Marino, University of the Republic of San Marino, Juridical Studies Department, 2010 31 A. Executive Summary 1. The Statutes "Leges Statuae Reipublicae Sancti Marini" that came into force in 1600 and the Laws that reform such Statutes represented the written source for excellence of the Sammarinese legal system. -

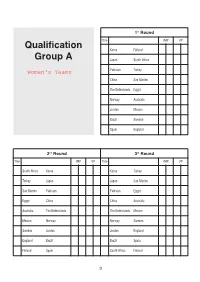

WBF Wroclaw 2016 Schedule Open

1st Round TbleIMP VP Qualification Korea Finland Group A Japan South Africa Pakistan Turkey China San Marino The Netherlands Egypt Norway Australia Jordan Mexico Brazil Sweden Spain England 2nd Round 3rd Round TbleIMP VP TbleIMP VP South Africa Korea Korea Turkey Turkey Japan Japan San Marino San Marino Pakistan Pakistan Egypt Egypt China China Australia Australia The Netherlands The Netherlands Mexico Mexico Norway Norway Sweden Sweden Jordan Jordan England England Brazil Brazil Spain Finland Spain South Africa Finland 3 4th Round 5th Round TbleIMP VP TbleIMP VP San Marino Korea Korea Egypt Egypt Japan Japan Australia Australia Pakistan Pakistan Mexico Mexico China China Sweden Sweden The Netherlands The Netherlands England England Norway Norway Spain Spain Jordan Jordan Brazil Finland Brazil San Marino South Africa South Africa Turkey Turkey Finland 6th Round 7th Round TbleIMP VP TbleIMP VP Australia Korea Korea Mexico Mexico Japan Japan Sweden Sweden Pakistan Pakistan England England China China Spain Spain The Netherlands The Netherlands Brazil Brazil Norway Norway Jordan Finland Jordan Australia South Africa South Africa Egypt Egypt Turkey Turkey San Marino San Marino Finland 4 8th Round 9th Round TbleIMP VP TbleIMP VP Sweden Korea Korea England England Japan Japan Spain Spain Pakistan Pakistan Brazil Brazil China China Jordan Jordan The Netherlands The Netherlands Norway Finland Norway Sweden South Africa South Africa Mexico Mexico Turkey Turkey Australia Australia San Marino San Marino Egypt Egypt Finland 10th Round 11th Round -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

The Road to Peace in the Balkans Is Paved with Bad Intentions

Pregledni rad Gregory R. Copley 1 UDK: 327.5(497) THE ROAD TO PEACE IN THE BALKANS IS PAVED WITH BAD INTENTIONS (An Address to the Conference on A Search for a Roadmap to Peace in the Balkans, organized by the Pan-Macedonian Association, Washington, DC, June 27, 2007) This conference is aptly titled “A Search for a Roadmap to Peace in the Balkans”, because we have yet to find a road map, let alone, should we find it, the right road to take. In any event, because of the short-term thinking, greed, fear, and ignorance which have plagued decision making with regard to the region by players inside it and out, the road to peace in the Balkans is paved with bad intentions. The short-term thinking, greed, fear, and ignorance have plagued decision making with regard to the region by players inside it and out. As a consequence, the road to peace in the Balkans is paved with bad intentions. It has been long and widely forecast that the security situation in the Balkans — indeed, in South-Eastern Europe generally — would become delicate, and would fracture, during the final stages of the Albanian quest for independence for the Serbian province of Kosovo and Metohija. As pessimistic as those forecasts were, however, the situation was considerably worsened by the eight-hour visit to Albania on June 10, 1 Gregory Copley is President of the International Strategic Studies Association (ISSA), based in Washington, DC, and also chairs the Association’s Balkans & Eastern Mediterranean Policy Council (BEMPC). He is also Editor of Defense & Foreign Affairs publications, and the Global Information System (GIS), a global intelligence service which provides strategic current intelligence to governments worldwide. -

Foreign Policy Concepts Conjuncture, Freedom of Action, Equality

Foreign Policy Concepts Conjuncture, Freedom of Action, Equality Reşat Arım Ambassador (Rtd.) Dış Politika Enstitüsü – Foreign Policy Institute Ankara, 2001 CONTENTS Introduction 3 The Study of Some Concepts: Conjuncture, Freedom of Action, Equality 3 Conjuncture 5 A Historical Application Of The Concept Of Conjuncture: The Ottoman Capitulations 6 Application Of The Concept To Actual Problems 8 Relations with Greece 8 The Question of Cyprus 18 The Reunification of Germany 21 The Palestine Question 22 Freedom Of Action 29 A Historical Application: The Ottoman Capitulations 29 Application in Contemporary Circumstances 30 Neighbours: Russia, Syria and Iraq 30 Geopolitics 33 Some Geopolitical Concepts: Roads, Railroads, Pipelines 35 Agreements 41 Equality 44 A Historical Application: The Capitulations 45 Equality in Bilateral Relations 47 Equality in the Context of Agreements 48 International Conferences and Organizations 51 The Method Of Equality Line 52 Conclusions 54 2 INTRODUCTION Turkey’s foreign policy problems are becoming more numerous, and they are being exam- ined by a wider range of people. In order to help promote a systematic analysis of our interna- tional problems in various institutions, the formulation of concepts would be of great use. When we debate foreign policy problems, we want to find answers to some questions: 1. How can we find solutions to problems with our neighbours? 2. What would be the best way to tackle issues with the European Union? 3. Which is the determining factor in our relations with the United States? 4. To which aspect of our relations with Russia should we pay more attention? 5. What are Turkey’s priorities in her relations with the Central Asian republics? 6. -

The Influence of External Actors in the Western Balkans

The influence of external actors in the Western Balkans A map of geopolitical players www.kas.de Impressum Contact: Florian C. Feyerabend Desk Officer for Southeast Europe/Western Balkans European and International Cooperation Europe/North America team Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Phone: +49 30 26996-3539 E-mail: [email protected] Published by: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e. V. 2018, Sankt Augustin/Berlin Maps: kartoxjm, fotolia Design: yellow too, Pasiek Horntrich GbR Typesetting: Janine Höhle, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Diese Publikation ist/DThe text of this publication is published under a Creative Commons license: “Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 international” (CC BY-SA 4.0), https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-sa/4.0/legalcode. ISBN 978-3-95721-471-3 Contents Introduction: The role of external actors in the Western Balkans 4 Albania 9 Bosnia and Herzegovina 14 Kosovo 17 Croatia 21 Macedonia 25 Romania 29 Serbia and Montenegro 32 The geopolitical context 39 3 Introduction: The role of external actors in the Western Balkans by Dr Lars Hänsel and Florian C. Feyerabend Dear readers, A spectre haunts the Western Balkans – the spec- consists of reports from our representatives in the tre of geopolitics. Once again, the region is at risk various countries involved. Along with the non-EU of becoming a geostrategic chessboard for exter- countries in the Western Balkans, this study also nal actors. Warnings are increasingly being voiced considers the situation in Croatia and Romania. in Brussels and other Western capitals, as well as in the region itself. Russia, China, Turkey and the One thing is clear: the integration of the Western Gulf States are ramping up their political, eco- Balkans into Euro-Atlantic and European struc- nomic and cultural influence in this enclave within tures is already well advanced, with close ties and the European Union – with a variety of resources, interdependencies. -

Paris Peace Conference 1919-1920: Results Key Words: Treaty Of

Paris Peace Conference 1919-1920: Results Key words: Treaty of Versailles, Treaty of Saint-Germain, Treaty of Neuilly, Treaty of Trianon, Treaty of Sèvres, Treaty of Lausanne Paris Peace Settlement Country Name of the Treaty Year when the treaty was signed Germany Treaty of Versailles 28 June 1919 Austria Treaty of Saint-Germain 10 September 1919 Bulgaria Treaty of Neuilly 27 November 1919 Hungary Treaty of Trianon 4 June 1920 Ottoman Empire Treaty of Sèvres, subsequetly Sèvres: 10 August 1920 revised by the Treaty of Lausanne Lausanne: 24 July 1923 Work for you to do: Get divided into three delegations: American, British and French. Each delegation should use the ideas from the class before to work out their proposed decision on each of the ideas and questions below. Remember to argue from the point of view of each country. Once each delegation has worked out its proposals, the whole class should discuss each issue and then vote on it. Important issues and types of questions to do: Will you make Germany guilty of starting the war? Will you limit German armed forces? Should Germany pay for the war? If so, how much? Should Germany lose some of its territories in Europe? What would you do with the German colonies? Would you promote establishing the League of Nations? Would you promote “self- determination policy” ask for dissolution of Austria-Hungary and Ottoman Empire? 1. The Treaty of Versailles: ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. -

Treaty of Lausanne Pdf in Urdu

Treaty of lausanne pdf in urdu Continue A peace treaty between the Republic of Turkey and the Allied powers at the end of the Turkish War of Independence, replacing the Treaty of Sevres for other purposes, see the Treaty of Lausanne (disambiguation). Treaty of Lausanne Long name: Treaty on peace and exchange of prisoners of war with Turkey, signed in LausanneAccord relatif a la restitution r'ciproque de intern's civil and l'change de prisonniers de guerre, To sign the Lausanne borders of Turkey established by the Treaty of Lausanne24 July 1923PostationLausanne, SwitzerlandEffected6 August 19241924After ratification by Turkey and any three of the United Kingdom, France, Italy and Japan, the treaty would come into force for those high contracting parties and in the future for each additional signatory to the ratification fieldIntinor France Italy Turkey DepositaryFrenchricte Treaty of Lausanne on Wikisource Treaty Lausanne (French: Tribe de Lausanne) was a peace treaty agreed during the Lausanne Conference 1922-23 Lausanne, Switzerland, July 24, 1923. It officially settled the conflict that originally existed between the Ottoman Empire and the Federal French Republic, the British Empire, the Kingdom of Italy, the Japanese Empire, the Kingdom of Greece and the Kingdom of Romania since the outbreak of World War I. This was the result of the second attempt of peace after the failed Sevres Treaty. The previous treaty was signed in 1920, but was later rejected by the Turkish national movement, which fought against its conditions. The Treaty of Lausanne put an end to the conflict and defined the borders of the modern Turkish Republic. -

The Macedonian Question: a Historical Overview

Ivanka Vasilevska THE MACEDONIAN QUESTION: A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW There it is that simple land of seizures and expectations / That taught the stars to whisper in Macedonian / But nobody knows it! Ante Popovski Abstract In the second half of the XIX century on the Balkan political stage the Macedonian question was separated as a special phase from the great Eastern question. Without the serious support by the Western powers and without Macedonian millet in the borders of the Empire, this question became a real Gordian knot in which, until the present times, will entangle and leave their impact the irredentist aspirations for domination over Macedonia and its population by the Balkan countries – Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia. The consequence of the Balkan wars and the World War I was the territorial dividing of ethnic Macedonia. After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the territory of Macedonia was divided among Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria, an act of the Balkan countries which, instead of being sanctioned has received an approval, with the confirmation of their legitimacy made with the treaties introduced by the Versailles world order. Divided with the state borders, after 1919 the Macedonian nation was submitted to a severe economic exploitation, political deprivation, national non-recognition and oppression, with a final goal - to be ethnically liquidated. In essence, the Macedonian question was not recognized as an ethnic problem because the conditions from the past and the powerful propaganda machines of the three neighboring countries - Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria, made the efforts to make the impression before the world public that the Macedonian ethnicity did not exist, while Macedonia was mainly treated as a geographical term, and the ethnic origin of the population on the Macedonian territory was considered exclusively as a “lost herd”, i.e. -

Tomasz KAMUSELLA ALBANIA

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 96 E-ISSN 2537–6152 REVISTA DE ETNOLOGIE ŞI CULTUROLOGIE Chișinău, 2016 Volumul XX Tomasz KAMUSELLA ALBANIA: A DENIAL OF THE OTTOMAN PAST (SCHOOL TEXTBOOKS AND POLITICS OF MEMORY)1 Rezumat Summary Albania: negarea trecutului otoman (manualele Albania: A Denial of the Ottoman past (School şcolare şi politicile de conservare a memoriei) textbooks and politics of memory) În şcolile din Albania postcomunistă, pe lângă ma- In post-communist Albania’s schools, alongside reg- nualele destinate pentru predarea istoriei, de asemenea, în ular textbooks of history for teaching the subject, school calitate de material didactic suplimentar sunt utilizate şi atlases of history are also employed as a prescribed or atlasele şcolare. Faptele şi relatările istorice ale trecutului adjunct textbook. In the stories and facts related through otoman, menţionate atât prin texte cât şi prin hărţi, sunt in- texts and maps, the Ottoman past is curiously warped discret denaturate şi marginalizate. Ca rezultat, în prezent, and marginalized. As a result, the average Albanian is left cetăţeanul albanez este incapabil să explice de ce în Albania, incapable of explaining why Albania is a predominantly unde predomină un sistem de guvernământ musulman, în Muslim polity, but with a considerable degree of tolerant acelaşi timp persistă un grad considerabil de toleranţă poli- poly-confessionalism. Furthermore, school history educa- confesionalistă. Cu toate acestea, curricula şcolară albaneză tion in Albania propagates the unreflective anti-Ottoman la disciplina „Istorie” continuă să propage în mod denaturat feeling encapsulated by the stereotypes of ‘Turkish yoke’ sentimentul antiotoman încapsulat de stereotipurile „jugul or ‘the five centuries of Turkish occupation.’ This simplis- turcesc” sau „cinci secole de ocupaţie turcească”.