What Are We Missing? Rethinking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2005 Inside

the CARDINALSt. Charles Preparatory School Alumni Magazine Spring 2005 Inside Joel I. Klein is a “non-traditional” superintendent of the New York City School system. Read how this “change agent” is working to transform a public school system facing many serious challenges and his warning that globalization will not tolerate unprepared students in the workforce. Page 4 1958 alumnus Frederick Gottemoeller is a world- recognized expert in the field of bridge design aesthetics. Read about his distinguished career in architecture and transportation planning, as well as the role former St. Charles teacher Fr. Charles A. Haluska played in influencing his academic and professional successes. Page 6 The freedoms some Americans take for granted have been afforded us by the supreme and ultimate sacrifices of those in the armed forces. In a special section, we honor St. Charles alumni and family members currently serving in the military — in some of the most dangerous places on earth. Read about their personal accounts from abroad, updates on a historic group of graduates in 1989 as many current military alumni as we could find, and a special gift to soldiers being deployed to Iraq. Page 8 Last November St. Charles recognized four members of its community with The Borromean Medals and Principal’s Award, the school’s highest honors. Read about Fr. Robert Schwenker ’54, Dr. Daniel Rankin III ’53 and faculty members Ann Cobler and Doug Montgomery — all noted Honoring Service to Country their service and dedication for their distinguished service and Many alumni attend military academies, dedication. Page 25 serve in U.S. -

Sponsorship Opportunities March 8-11 2019

A THINK SPACE FOR BLACK INNOVATORS SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES MARCH 8-11 2019 MVMT50.COM The future is not being written by laws in Washington. It’s being written by coders in Silicon Valley. VAN JONES “ President, Rebuild the Dream ” SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITIES ABOUT MVMT50 A THINK SPACE FOR BUILD COHESION BLACK INNOVATORS The conversation and consequences of diversity and inclusion deficiencies across the technology sector influence a wide variety MVMT50 is a coalition of Black thought leaders committed to sus- of industry sectors; from large Fortune 500 companies and small, tained and systematic improvement in employment diversity, local businesses, to the service providers that keep tech companies cultural representation and leadership development in the innova- running and relevant. Seeing the needle move requires cohesion on tion, technology and digital sectors. MVMT50 represents a dimension priorities and the use of resources amongst these community mem- of the 21st Century’s civil rights movement, with intent to expand bers. MVMT50’s partnership with SXSW, “the most important inter- opportunity, elevate the value of diversity and disrupt the tradition- active event in the world” (CNET), is a conduit to build cohesion and al culture and practices associated with the innovation sector. Our cooperation amongst the many needed voices. SXSW Interactive is partners and participants gather annually during South By South- where we connect, collaborate and create consensus on how to ele- west (SXSW) Interactive to connect, collaborate and build consensus vate and empower our individual and collective spaces of influence. around disruptive and innovative solutions to empower and elevate Black thought leadership. Today’s American mainstream is rapidly changing, and that change can be attribut- ed, in part, to the growth and activities “of African-Americans in the marketplace. -

Sustaining Our Momentum in Public and Private Arenas

UNITED WE THRIVE Sustaining Our Momentum in Public and Private Arenas 2016 ANNUAL REPORT MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR FY2016 has been a productive year for the National Women’s Business Council and a year full of progress for women entrepreneurs. The Senate and the House Small Business Committees each passed bills that aimed to raise the grant ceiling for the Small Business Administration’s Women’s Business Center program for the first time since the original authorization, H.R. 5050, created this program in 1988. In June, the White House convened the first ever national summit focusing on women — The United State of Women — looking at gender issues across all areas. While women entrepreneurs have always been a backbone of this country’s economy, this unprecedented action by the federal government recognizes the influence that women business owners continue to have on its growth and success. Our economy is better than it was eight years ago, and we celebrate that a significant contribution to this stronger, more durable economy has been, in part, made by women business owners as they have originated and scaled their businesses. In March, the Council released a report based on data from The Council also looked at access to private markets for women the 2012 Survey of Business Owners and Self-Employed Persons, business owners, initiating original research on corporate supplier confirming that women-owned businesses now comprise 36 diversity programs. Corporate supplier diversity programs are percent of the country’s businesses and women continue to corporations’ explicit effort to include, into their supply chains, enter the ranks of U.S. -

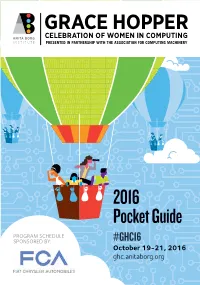

2016 Pocket Guide

2016 Pocket Guide PROGRAM SCHEDULE SPONSORED BY: #GHC16 October 19-21, 2016 ghc.anitaborg.org Check out our Clusters, which physically group similar tracks to help navigate and explore topics. CAREER ORGANIZATION CAREER TRANSFORMATION ORGANIZATION WEDNESDAY, COMMUNITY TRANSFORMATION CRA-W PRODUCTS A TO Z FACULTY PRODUCTS A TO Z EMERGING TECH/ OCTOBER 19 BEST OF TECHNOLOGY BEST OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IoT/ WEARABLE TECH COMPUTER SYSTEMS GENERAL SESSIONS ENGINEERING KEYNOTES DATA SCIENCE PLENARIES GAMING, GRAPHICS & ANIMATION SPECIAL SESSIONS SPECIAL SESSIONS HUMAN COMPUTER INTERACTION OPEN SOURCE WORLD SECURITY/PRIVACY OPEN SOURCE SOFTWARE ENGINEERING LOCATION LEGEND: GRB: GEORGE R. BROWN CONVENTION CENTER HILTON: HILTON AMERICAS SESSIONS DAY 1: WEDNESDAY SESSIONS DAY 1: WEDNESDAY 9:00 a.m. - 11:30 a.m. 2:00 p.m. - 3:15 p.m. KEYNOTE PLENARIES ORGANIZATION TRANSFORMATION Women and the Future of Tech Quiet: How to Harness the Strengths of Introverts Toyota Center Ginni Rometty (IBM), Latanya to Transform How We Work, Lead and Innovate Sweeney (Harvard University; Technology Science; GRB General Assembly Susan Cain (Author, Chief Data Privacy Lab) and more Revolutionary and Co-Founder of Quiet Revolution) 12:00 p.m. - 6:00 p.m. PLENARIES TECHNOLOGY Featured Speaker: Astro Teller (Captain of EXPO Moonshots for X) Career Fair GRB Hall E GRB Halls B-D PLENARIES PRODUCTS A TO Z 12:00 p.m. - 7:00 p.m. Product Announcements GRB Hall A3 EXPO Interviews 2:00 p.m. - 4:00 p.m. GRB Hall A SPECIAL SESSIONS SPECIAL SESSIONS Student Node sponsored by D.E. Shaw & Co. Want to be a Bias Interruptor? GRB Balcony D GRB 360 A Valerie Barr (Union College), Latanya Sweeney (Harvard University), Brad McLain (NCWIT), Tracy Camp (Colorado School of Mines), Lucy Sanders (NCWIT) SESSIONS DAY 1: WEDNESDAY SESSIONS DAY 1: WEDNESDAY 2:00 p.m. -

Saks Upends Luxury Market with Strategy to Slash Prices - WS

Saks Upends Luxury Market With Strategy to Slash Prices - WS... http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123413532486761389.html?mo... More News, Quotes, Companies, Videos SEARCH Monday, February 9, 2009 as of 6:12 AM EST POLITICS Welcome, Cherrie Clark Logout My Account My Online Journal Help U.S. Edition Today's Paper Video Columns Blogs Graphics Journal Community Home World U.S. Business Markets Tech Personal Finance Life & Style Opinion Careers Real Estate Small Business Politics Obama's First 100 Days Inauguration Day Rod Blagojevich Journal Reports Columns & Blogs 1 of 10 2 of 10 3 of 10 TOP STORIES IN U.S. Senate Nears Partisan Divide Haunts Hathaway to Head California's U.S. Vote on Stimulus Obama's Policy Cybersecurity Post Tough-Guy Bill Controller FEBRUARY 9, 2009, 7:12 A.M. ET Saks Upends Luxury Market With Strategy to Slash Prices Article Comments (13) MORE IN POLITICS » Email Printer Friendly Share: Yahoo Buzz Text Size By VANESSA O'CONNELL and RACHEL DODES When Saks Fifth Avenue slashed prices by 70% on designer clothes before the holiday season even began, shoppers stampeded. "It was like the running of the bulls," says Kathryn Finney, who says she was knocked to the floor in New York's flagship store by someone lunging for a pair of $535 Manolo Blahnik shoes going for $160. Saks's deep, mid-November markdowns were the first tug on a thread that's now unraveling long-established rules of the luxury-goods industry. The changes are bankrupting some firms, toppling longstanding agreements on pricing and distribution, and destroying the very air of exclusivity that designers are trying to sell. -

How Philanthropy Can Unlock Capital for Women Entrepreneurs And

FEBRUARY 2019 AN ECONOMY FOR ALL How Philanthropy Can Unlock Capital for Women Entrepreneurs and Entrepreneurs of Color through Inclusive Investing ABOUT THIS REPORT With support from JPMorgan Chase & Co., the New Venture Fund’s Harriet Ecosystem Initiative partnered with Arabella Advisors to produce this report. ABOUT JPMORGAN CHASE JPMorgan Chase & Co. (NYSE: JPM) is a leading global financial services firm with assets of $2.6 trillion and operations worldwide. The firm is a leader in investment banking, financial services for consumers and small businesses, commercial banking, financial transaction processing, and asset management. A component of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, JPMorgan Chase & Co. serves millions of customers in the United States and many of the world’s most prominent corporate, institutional, and government clients under its J.P. Morgan and Chase brands. Information about JPMorgan Chase & Co. is available at www.jpmorganchase.com. ABOUT THE NEW VENTURE FUND The New Venture Fund, a 501(c)(3) established in 2006, conducts public interest projects and provides professional insight and support to institutions and individuals seeking to foster change through strategic philanthropy. To learn more, visit www.newventurefund.org. ABOUT ARABELLA ADVISORS Arabella Advisors helps foundations, philanthropists, and investors who are serious about impact create meaningful change. We help our clients imagine what’s possible, design the best strategies, learn what works best, and do the work necessary to turn their visions into reality. To learn more, visit www.arabellaadvisors.com. The following members of the Arabella Advisors team contributed to this report: Dan Cabrera, Gareth Fowler, Alissa Gulin, Cyrus Kharas, Molly Lyons, Loren McArthur, Shelley Whelpton, and Zoe Wong. -

Download Magazine

UCLA SCHOOL OF LAW BOARD OF ADVISORS Michael T. Masin '69, Co-Chair Kenneth Ziffren '65, Co-Chair Nancy Abell '79 James D. C. Barrall '75 Jonathan F. Chait '75 Stephen E. Claman '59 Deborah David '75 Hugo D. de Castro '60 David J. Epstein ‘64 Edwin F. Feo ‘77 David Fleming '59 Arthur N. Greenberg '52 Bernard Greenberg '58 Antonia Hernandez '74 Joseph K. Kornwasser ‘72 Stewart C. Kwoh ‘74 Louis M. Meisinger ‘67 Wendy Munger ‘77 Greg M. Nitzkowski ‘84 Nelson C. Rising '67 UCLA LAW Paul S. Rutter ‘78 Ralph J. Shapiro '58 The Magazine of the School of Law The Honorable David Sotelo ‘86 Vol. 29 / No. 1 / Fall 2006 Bruce H. Spector ‘67 Robert J. Wynne '67 © 2006 Regents of the University of California The Honorable Kim Wardlaw ‘79 UCLA School of Law Office of Communications Box 951476 UCLA LAW ALUMNI ASSOCIATION BOARD OF Los Angeles, California 90095-1476 DIRECTORS Greg Ellis '85, President Michael H. Schill Dean and Professor of Law Donna Wells '92, Vice President Laura Lavado Parker, Assistant Dean, External Affairs Honorable Steven Z. Perren '67, Past President Philip Little, Director of Communications Leslie Cohen '80 Editor Anne Greco Larry Ebiner '85 Assistant Director of Communications Rasha Gerges '01 Honorable Joe W. Hilberman '73 Design Francisco A. Lopez Michael Josephson '67 Manager of Publications and Graphic Design Pamela Kelly '86 David Kowal '96 Contributing Writers Liz Furmanchik Karin Krogius '82 Dan Gordon Ronald Lazof '71 David Greenwald Thomas Mabie '79 Scott Woolley, Forbes Magazine Martin Majestic '67 The Honorable Jon Mayeda '71 Photography Edward Carreon, Carreon Photography Vernon Thomas Meader '78 Todd Cheney, ASUCLA Photography Jay Palchikoff '82 Don Liebig, ASUCLA Photography Wilma Pinder '76 William Short, ASUCLA Photography George Ruiz '92 Rick Runkel '81 The Honorable George Schiavelli '74 Printer The Castle Press Gary Stabile '67 Pasadena, Calif. -

Media 2070: an Invitation to Dream up Media Reparations

An Invitation to Dream Up Media Reparations AN INVITATION TO DREAM UP MEDIA REPARATIONS Collaborators: Joseph Torres Alicia Bell Collette Watson Tauhid Chappell Diamond Hardiman Christina Pierce a project of Free Press 2 WWW.MEDIA2070.ORG CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 9 I. A Day at the Beach 13 II. Media 2070: An Invitation to Dream 18 III. Modern Calls for Reparations for Slavery 19 IV. The Case for Media Reparations 24 V. How the Media Profited from and Participated in Slavery 26 VI. The Power of Acknowledging and Apologizing 29 VII. Government Moves to Suppress Black Journalism 40 VIII. Black People Fight to Tell Our Stories in the Jim Crow Era 43 IX. Media Are the Instruments of a White Power Structure 50 X. The Struggle to Integrate Media 52 XI. How Public Policy Has Entrenched Anti-Blackness in the Media 56 XII. White Media Power and the Trump Feeding Frenzy 58 XIII. Media Racism from the Newsroom to the Boardroom 62 XIV. 2020: A Global Reckoning on Race 66 X V. Upending White Supremacy in Newsrooms 70 XVI. Are Newsrooms Ready to Make Things Right? 77 XVII. The Struggles of Black Media Resistance 80 XVIII. Black Activists Confront Online Gatekeepers 83 XIX. Media Reparations Are Necessary to Our Nation’s Future 90 XX. Making Media Reparations Real 95 Epilogue 97 About Team Media 2070 98 Definitions 99 #MEDIA2070 3 TRIGGER WARNING There are numerous stories in this essay that explore the harms the news media have inflicted on the Black community. While these stories may be difficult or painful to read, they are not widely known, and they need to be. -

Elevating Women in Entrepreneurship

v v ELEVATING WOMEN IN ENTREPRENEURSHIP ERIKA R. SMITH BRITA BELLI Written by Erika R. Smith and Brita Belli. Edited by Liv Sunná and Jen Mountain. Copyright © 2018 by Erika R. Smith and Brita Belli. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Published by InBIA. International Business Innovation Association 3361 Rouse Road #200, Orlando, FL, 32817 This research was made possible by JPMorgan Chase & Co. through Small Business Forward, a five year, $150 million initiative connecting underserved small businesses with the capital, targeted assistance and support networks to help them grow faster, create jobs and strengthen local economies. To drive impact, Small Business Forward focuses on diversifying high-growth sectors, expanding entrepreneurial opportunities in neighborhoods and expanding access to flexible capital for underserved entrepreneurs. The views and opinions expressed in the report are those of the International Business Innovation Association and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of JPMorgan Chase & Co. or its affiliates. 1 2 INTRODUCTION 3 There is broad recognition that we need more women in entrepreneurship to capitalize on the opportunities offered by women-led businesses and revitalize the U.S. economy. Through this playbook, we have curated best practices from the nation’s top entrepreneurship centers, who are interested in strategies for recruiting more women and addressing barriers to success. We intend to create a resource for entrepreneurship center executives and leadership teams with tangible takeaways that aim to not just intentionally impact entrepreneurship centers, but to set the stage for significant change within their communities. -

REIMAGINE AGING We’Re a Big Fan of Different

Is Sugar Evil? Winter 2016 Leadership empowerment for women who mean business MEET THE Stars Who FAIL SAFE Mean Failure Can Business Be Good Peer Award for You Winners Jo Ann Jenkins Wants you to REIMAGINE AGING We’re a big fan of different. At Target, we believe that the most important part of our business is our people. The diverse backgrounds, ethnicities and experiences are what make work fun, interesting and new. We attribute our success to our Team Members and the ideas they bring to work TM every day. To learn more about the diverse team at Target, visit Target.com/diversity. ©2014 Target Brands, Inc. The Bullseye Design and Target are registered trademarks of Target Brands, Inc. 123300 Leadership empowerment for women Contents WINTER 2016 who mean business > VOL. 7, ISSUE 1 Katrina Adams 37 Features Jo Ann Jenkins The CEO of AARP is 37 helpingtoredefineage 50 and beyond. Stars Who Mean Business Celebrating our 2015 43 Diversity Woman Peer Award winners. Upfront 5 Minutes with … Ana Duarte McCarthy of Citi. 11 The Office Handling racist remarks intheoffice. 12 DW Hot List Our top picks for cloud-based storage services. 12 Shortcuts Saying no gracefully. 13 Etc. Getting to the bottom of the C-suite gender gap. 13 Stars Who Mean Business Gloria Estefan bringsashotofCubanflavortoherFlorida restaurants and resorts. 14 Next Kathryn Finney gives black women entrepreneurs a boost. 15 ON THE Jo Ann Jenkins Versus COVER Cover photography by Women on our TV screens, then and now. 15 fabiocamarastudios.com Anatomy of a … conference call. 17 diversitywoman.com Winter 2016 DIVERSITY WOMAN 1 REDEFINETHE WORKPLACE EMC2, EMC, and the EMC logo are registered trademarks or trademarks of EMC Corporation in the United States and other countries. -

Hurricane Katrina Rricane Katrina and Stereotyping D Stereotyping

Hurricane Katrina And Stereotyping - Media Portrayals of African Americans During Katrina Anne Hansen March 2012 Cand.ling.merc. Copenhagen Business School Number of characters: 181.988/Pages 80 Supervisor: Jan Gustafsson Institute: Internationale Kultur- og Kommunikationsstudier 2 Dansk Resume Hurricane Katrina Og Stereotypering: Skildringer Af Afroamerikanere Under Hurricane Katrina Dette speciale har til formål at undersøge hvordan sorte amerikanere blev fremstillet i medierne under dækningen af Hurricane Katrina. Dette speciale formoder at sorte blev dækket ved brug af race-stereotyper og at Othering (skelnen og separation mellem ind-gruppe og ud-gruppe) fremkom i dækningen. Derudover formodes det at de roller, ofrene for Katrina blev dækket i, varierede racerne imellem, dvs. at sorte og hvide blev portrætteret i forskellige roller og at disse passer med eksisterende race-stereotyper. Sorte blev primært fremstillet som kriminelle og dette blev gjort gennem fokus på sort kriminalitet, der blev portrætteret som værende ude af kontrol. De fleste af historierne om kriminalitet blev afvist efter Katrina og viste sig at have været baseret på rygter. Det der gjorde dem troværdige var stereotypen om sorte kriminelle og historierne blev derfor dækket som værende faktuelle. Sorte blev ligeledes bebrejdet for ikke at have evakueret New Orleans inden orkanen, men i stedet være blevet tilbage og derfor havde bragt sig selv i en situation, hvor de skulle reddes. At sorte fattige ikke havde kunnet evakuere, fordi de ikke havde råd og ikke ejede biler, blev sjældent nævnt og resultatet var en ”bebrejd offeret”-tone i dækningen af sorte og at sorte blev portrætteret som de stereotype sorte fattige, som er uansvarlige og ikke fortjener hjælp. -

Committee to Protect Journalists 2008 Annual Report Mission

Committee to Protect Journalists 2008 Annual Report www.cpj.org Mission The Committee to Protect Journalists works to promote press freedom worldwide. We take action when journalists are censored, jailed, kidnapped, or killed for their efforts to tell the truth. In our defense of journalists, CPJ protects the right of all people to have access to diverse and independent sources of information. CPJ has been a leading voice in the global press freedom movement since its founding in 1981. We defend journalists and news organizations without regard to political ideology. To maintain our independence, CPJ accepts no government funding. We are supported entirely by private contributions from individuals, foundations, and corporations. Brian Frank/CPJ Brian ing to CPJ research. Most of these journalists were not killed by an errant bullet on the battlefield but were deliberately targeted for their reporting. Even in war zones, murder is the leading cause of death for journal- ists. And in the vast majority of cases—more than 85 percent—the killers go free. With these grim statistics in mind, CPJ launched its Global Campaign Against Impunity to bring the killers of journalists to justice. The campaign’s initial focus is on Russia and the Philippines—two countries that are among the world’s deadliest for journalists and among the worst in solving these murders. Already we are be- From the Executive Director ginning to see results, with investigative and judicial action in several high-profile cases selected by CPJ for Dear Friends: sustained advocacy and attention. This report covers a tumultuous year for the me- CPJ has also mounted wide-ranging campaigns to dia industry and for press freedom worldwide.