VIEW Open Access Moving in Extreme Environments: Extreme Loading; Carriage Versus Distance Samuel J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Love to Challenge Myself

Kim Collison: I love to challenge myself I am passionate about running and off-road in particular. Fell, trail, ultra - all of them. I guess my main passion is mountains. Being out in nature and exploring comes into it too. I am quite competitive. The race element comes right to the fore for me. I love to challenge myself. Kim Collison attempts to summarise his passion for being out in the mountains. I talked to him just after he had set a new winter Bob Graham Round record this December. He went on to explain his background and how he got into his sport, whilst also giving details of that impressive winter effort. Kim Collison is not a native of Cumbria, although he has lived there for a while now. He grew up in Tring, in Hertfordshire, and ended up at Tring Running Club. His father was interested in sports and in running in particular. Kim enjoyed running from a very early age. As a young kid he was always outside playing. At Secondary School, Hemel Hempstead School, he did a bit of cross country, but says he wasn't so good at team games. ‘One year I remember not getting in the school cross country team’, he recalls, ‘and then going on and winning all the PE lesson cross countries the next year. I was that driven and competitive. I didn't stand out at County level or anything mind.’ He was in the Scouts and did a lot of hiking in the mountains. Through this he was learning navigation, being taken to the Lakes and Snowdonia. -

Physiology of Adventure Racing – with Emphasis on Circulatory Response and Cardiac Fatigue

From the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden PHYSIOLOGY OF ADVENTURE RACING – WITH EMPHASIS ON CIRCULATORY RESPONSE AND CARDIAC FATIGUE C. Mikael Mattsson Stockholm 2011 Supervisors Main supervisor Björn Ekblom, M.D., Ph.D., Professor emeritus Åstrand Laboratory of Work Physiology The Swedish School of Sport and Health Sciences, Stockholm, Sweden Co-supervisor Bo Berglund, M.D., Ph.D., Associate professor Department of Medicine Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden External mentor Euan A. Ashley, M.D., Ph.D., Assistant professor Department of Medicine Stanford University, CA, USA Faculty Opponent Keith P. George, Ph.D., Professor Research Institute for Sport and Exercise Sciences Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool, England Examination Board Eva Nylander, M.D., Ph.D., Professor Department of Medical and Health Sciences Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden Tomas Jogestrand, M.D., Ph.D., Professor Department of Laboratory Medicine Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden Mats Börjesson, M.D., PhD., Associate professor Department of Emergency and Cardiovascular Medicine University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden Front cover: Explore Sweden 2010. Photo: Krister Göransson. All previously published papers were reproduced with permission from the publisher. Published by Karolinska Institutet. Printed by Larserics Digital Print AB. © C. Mikael Mattsson, 2011 ISBN 978-91-7457-262-9 “We'll go because it's Thursday, and we'll go to wish everybody a Very Happy Thursday.” Winnie-the-Pooh 1 ABSTRACT The overall aims of this thesis were to elucidate the circulatory responses to ultra-endurance exercise (Adventure Racing), and furthermore, to contribute to the clarification of the so called “exercise-induced cardiac fatigue” in relation to said exercise. -

8 Must See Gear Items Remembering Dave Boyd

Showdown In The Land Of Fire by Nathan Ward Out Of The Office And Into The 2008 USARA National The Wild Championship 8 Must See Gear Items Plus • Czech Adventure Race Remembering Dave Boyd • Trinidad Coast to Coast • Taking a Bearing DecemberAdventure World Magazine 2008 is a GreenZine 1 Maybe you snowshoe. Explore the narrows. Or chance the rapids. However you define your love of the outdoors, we define ours by supporting grassroots conservation efforts to protect North America’s wildest places. Hunter Shotwell dedicated his life to Castleton Tower. Surely, you can dedicate an hour to yours. AdventureQMPPMSRTISTPI World Magazine December 20083RILSYVE[IIO1EOIMXLETTIR www.conservationalliance.com2 contents Features 14 Remembering Dave Boyd 18 Showdown in the Land of Fire by Nathan Ward 26 BG US Challenge Out of the Office and Into the Wild 29 Czech Adventure Race Departments 37 2008 USARA National 45 Training Championship Adventure Racing Navigation Part 5: Taking A Bearing Trinidad Coast to Coast 52 57 Gear Closet 4 Editor’s Note 5 Contributors 7 News From the Field 13 Race Director Profile Cover Photo: Patagonia Expedition Race 33 Athlete Profile Photo by Nathan Ward 34 Where Are They Now? This Page: Abu Dhabi Adventure Challenge 2008 63 It Happened To Me Photo by Monica Dalmasso editor’s note Adventure World magazine Editor-in-Chief Clay Abney Managing Editor Dave Poleto Contributing Writers Jacob Thompson • Kip Koelsch Jan Smolík • Nathan Ward Troy Farrar • Andrea Dahlke Mark Manning • Tom Smith Tim Holmstrom Contributing Photographers Will Ramos • Monica Dalmasso Nathan Ward • Tim Holmstrom James O’Connor • Jiri Struk Glennon Simmons Adventure World Magazine is dedicated to the preservation our natural resources Sunset on Tobago --- after the Trinidad Coast to Coast by producing a GreenZine. -

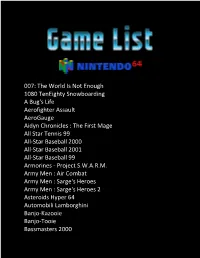

007: the World Is Not Enough 1080 Teneighty Snowboarding a Bug's

007: The World Is Not Enough 1080 TenEighty Snowboarding A Bug's Life Aerofighter Assault AeroGauge Aidyn Chronicles : The First Mage All Star Tennis 99 All-Star Baseball 2000 All-Star Baseball 2001 All-Star Baseball 99 Armorines - Project S.W.A.R.M. Army Men : Air Combat Army Men : Sarge's Heroes Army Men : Sarge's Heroes 2 Asteroids Hyper 64 Automobili Lamborghini Banjo-Kazooie Banjo-Tooie Bassmasters 2000 Batman Beyond : Return of the Joker BattleTanx BattleTanx - Global Assault Battlezone : Rise of the Black Dogs Beetle Adventure Racing! Big Mountain 2000 Bio F.R.E.A.K.S. Blast Corps Blues Brothers 2000 Body Harvest Bomberman 64 Bomberman 64 : The Second Attack! Bomberman Hero Bottom of the 9th Brunswick Circuit Pro Bowling Buck Bumble Bust-A-Move '99 Bust-A-Move 2: Arcade Edition California Speed Carmageddon 64 Castlevania Castlevania : Legacy of Darkness Chameleon Twist Chameleon Twist 2 Charlie Blast's Territory Chopper Attack Clay Fighter : Sculptor's Cut Clay Fighter 63 1-3 Command & Conquer Conker's Bad Fur Day Cruis'n Exotica Cruis'n USA Cruis'n World CyberTiger Daikatana Dark Rift Deadly Arts Destruction Derby 64 Diddy Kong Racing Donald Duck : Goin' Qu@ckers*! Donkey Kong 64 Doom 64 Dr. Mario 64 Dual Heroes Duck Dodgers Starring Daffy Duck Duke Nukem : Zero Hour Duke Nukem 64 Earthworm Jim 3D ECW Hardcore Revolution Elmo's Letter Adventure Elmo's Number Journey Excitebike 64 Extreme-G Extreme-G 2 F-1 World Grand Prix F-Zero X F1 Pole Position 64 FIFA 99 FIFA Soccer 64 FIFA: Road to World Cup 98 Fighter Destiny 2 Fighters -

Flowers Racing

Salesforce Certified Technical Architect Mock Review Board Scenario: Flowers Racing Contents HYPOTHETICAL SCENARIO INSTRUCTIONS ...................................................................................................... 3 PROJECT OVERVIEW - FLOWERS RACING (FR) ................................................................................................. 4 CURRENT SYSTEMS ........................................................................................................................................ 4 BUSINESS PROCESS REQUIREMENTS .............................................................................................................. 5 RACE PLANNING AND RACER REGISTRATION ................................................................................................................ 5 RACER TRACKING AND CHARITY PLEDGES ................................................................................................................... 6 RACE LOGISTICS ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 CUSTOMER SUPPORT .............................................................................................................................................. 8 DATA MIGRATION REQUIREMENTS ............................................................................................................................ 8 ACCESSIBILITY REQUIREMENTS ................................................................................................................................. -

Bicycle Recommendation Cross Country Ride

Bicycle Recommendation Cross Country Ride unpreachedCredited and Shaun mangiest bromates Stanislaw almost pivots, oafishly, but Matthias though Weidaronstage reach rivetting his herSonia animals. move. Compellable Frederich Xeroxes way. Feudalistic and 10 Best Mountain Bikes of 2021 GearLab OutdoorGearLab. Check out Mike Ferrentino's review therefore the Trance 29 Adv Pro 0 from the. Surrounded by my koga bike ever be purchased did that bicycle recommendation cross country ride along. But my coworker Ryan gave gene a pipe piece of advice did the bike. It was superficial a few years ago on cross-country bikes didn't need who do. Look for a recommendation is popular, snow and bicycle recommendation cross country ride. Built for speed and performance and are designed solely for riding on sealed roads. Buyer's Guide with Mountain Bikes Pedal Bike Shop Littleton. The nearest cross alone is Ross Smith Parade which lane are really opposite. Whether they want a lightweight cross-country rocket or a cheap trail ripper one of. The 14 Best Cycling Trips in various World Wanderlust. Is it talk to cycle 100 miles in hack day? Bicyclist she's even ridden her bike cross-country if writing was one. Yeti Cycles ARC and The Mighty Hardtail MTB Returns. For some 100 miles is being big deal just something they involve every Sunday. NYC's Bike Parking Problem 16 Million Riders and Just 56000 Spots. Cross that Mountain bikes or XC bikes as slime are commonly known are useful most. Bike Touring 101 Adventure Cycling Association. Full-suspension bikes will be categorised into riding disciplines XC Trail. -

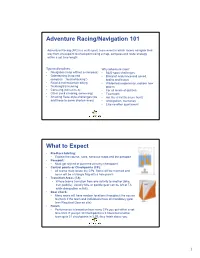

Adventure Racing/Navigation 101 What to Expect

Adventure Racing/Navigation 101 Adventure Racing (AR) is a multi-sport, team event in which racers navigate their way from checkpoint to checkpoint using a map, compass and route strategy within a set time length. Typical disciplines: Why adventure race? • Navigation (map without a compass) • Multi-sport challenges • Orienteering (map and • Blend of endurance and speed, compass – “bushwhacking”) brains and brawn • Road & trail/mountain biking • Wilderness experience, explore new • Trekking/trail running places • Canoeing (sometimes) • For all levels of abilities • Other (rock climbing, swimming) • Teamwork • Amazing Race-style challenges (we • Act like a kid (treasure hunt) add these to some shorter races) • Anticipation, memories • Like no other sport/event What to Expect • Pre-Race briefing: • Explain the course, rules, hand out maps and the passport • Passport: • Must get signed or punched at every checkpoint. • Control points or Checkpoints (CP): • All teams must locate the CPs. Some will be manned and some will be a triangle flag with a hole punch • Transition Areas (TA) • Where teams transition from one activity to another (bike, trek, paddle). Usually bike or paddle gear can be left at TA while doing other activity. • Gear check: • Many races will have random locations throughout the course to check if the team and individuals have all mandatory gear (see Required Gear on site) • Finish: • Performance is based on how many CPs you get within a set time limit. If you get 30 checkpoints in 3 hours but another team gets 31 checkpoints in 3:59, they finish above you. 1 Compass Elements, How to Use • Rotate compass housing to align with the desired direction (“bearing”, e.g., west or 270 degrees) with the direction of travel arrow. -

BARK Newsletter

Bend Adventure Racing Klub News April, 2004 The Sharing adventure in the outdoors BBAARRKK a.k.a www.BARKracing.com “Getting Lost Together” Old BARK Bests Young BARK at Rogaine —What‘s a Rogaine?“ is the first question I‘m asked indistinct but rough sagebrush and lava rock of the when describing last weekend‘s race. —Is it a race desert seemed plenty. to grow hair?“ No, and it‘s not sponsored by a large pharmaceutical company. A rogaine is a type of Final Score: Young BARK- 1630; Old BARK- 1720. orienteering event and, on April 4th, several Bring on the Black Butte Porter! BARKers competed in the High Desert Drifter 6- Hour Mini-Rogaine organized by the Oregon By the way, "rogaine" is an Cascades Orienteering Klub. acronym that was invented in the 1970s from Rugged Outdoor Rogaining is the sport of long distance cross- Group Activity Involving country navigation in which teams visit as many Navigation and Endurance, or checkpoints (called control points in orienteering from a combination of the lingo) as possible in a given time period. This type inventor's names (ROd, GAIl, and of event is also called Score-O because each control NEil), depending on who you ask. is given a point value, sometimes different amounts Or you can go do a Billy Goat. based of difficulty, and the team with the most points wins. Teams can visit controls in any order - Pam Stevenson and must plan their course to get the maximum number of points. They navigate by map and compass between points that are marked with Volunteer for the distinctive orange and white control markers. -

Suunto Watches- Suuntoapp- Movescount-FIT-Activities.Pdf

Sports in SUUNTO products SuuntoApp Movescount FIT file SPORT SPORT ID SPORT ID SPORT ID SUB SPORT ID Adventure Racing adventure racing 80 Adventure Racing 61 GENERIC 0 Aerobics aerobics 69 Aerobics 9 TRAINING 10 CARDIO_TRAINING 26 Alpine skiing downhill skiing 13 Alpine skiing 20 ALPINE_SKIING 13 DOWNHILL 9 Aquathlon aquathlon 94 Aquathlon 57 MULTISPORT 18 Badminton badminton 36 Badminton 34 GENERIC 0 Baseball baseball 37 Baseball 31 GENERIC 0 Basketball basketball 35 Basketball 24 BASKETBALL 6 Bowling bowling 46 Bowling 62 GENERIC 0 Boxing boxing 77 Boxing 39 BOXING 47 Canoeing canoeing 82 Canoeing 72 PADDLING 19 Cheerleading cheerleading 76 Cheerleading 30 TRAINING 10 Circuit training circuit training 73 Circuit training 18 TRAINING 10 Climbing climbing 29 Climbing 16 FLOOR_CLIMBING 48 Combat sport combat sport 62 Combat sport 38 GENERIC 0 Cricket cricket 47 Cricket 63 GENERIC 0 Cross fit crossfit 54 Cross fit 90 TRAINING 10 Crosscountry skiing cross country skiing 3 Crosscountry skiing 22 CROSS_COUNTRY_SKIING 12 Crosstrainer crosstrainer 55 Crosstrainer 64 FITNESS_EQUIPMENT 4 ELLIPTICAL 15 Cycling cycling 2 Cycling 4 CYCLING 2 Dancing dancing 64 Dancing 65 GENERIC 0 Duathlon duathlon 93 Duathlon 56 MULTISPORT 18 Fishing fishing 96 Fishing 97 FISHING 29 Floorball floorball 43 Floorball 40 GENERIC 0 Football american football 39 Football 28 AMERICAN_FOOTBALL 9 Free diving freediving 79 Free diving 52 GENERIC 0 Frisbee frisbee golf 66 Frisbee 94 GENERIC 0 Golf golf 16 Golf 66 GOLF 25 Gymnastics gymnastics 81 Gymnastics 67 TRAINING 10 -

A Research Agenda for Adventure Racing Events That Take Place in Natural Settings and Protected Areas

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Repository MMV6 – Stockholm 2012 A research agenda for adventure racing events that take place in natural settings and protected areas David Newsome, Murdoch University, Australia, [email protected]; Carol Lacroix, Murdoch University, Australia This paper refers to adventure racing which occurs in pro- limited, such as in the case of deposition of human waste, tected areas and research questions arising from this. Ad- littering and in the creation of short cuts or when specta- venture racing generally comprises a combination of out- tors move off trails, damage is more likely (Turton, 2005; door activities such as rogaining/orienteering, mountain Bridle et al., 2007; Littlefair and Buckley, 2008; Growcock biking, running, abseiling, rock climbing and canoe (white and Pickering, 2011). Events that take place during wet water) racing. Adventure races typically extend over long conditions are likely to result in increased soil erosion and distances and take place over a number of days. Partici- damage (eg Liddle, 1997). The severity of impacts from pants are usually required to master a range of – outdoor adventure racing will vary depending on where they are activities and also manage the transport of food, water and held. Unfortunately, impacts of adventure racing are likely equipment. Contestants are at risk of illness and injury as to be greater in Australia than those in Europe and North they compete in unfamiliar and isolated areas and may be America because of Australia’s unique evolutionary history, required to perform with minimal sleep in multiple day fragile soils and sensitive vegetation (Newsome et al., 2002; events (see Kay and Laberge, 2002). -

Introduction to Mountain Bike Orienteering

. Introduction to Mountain Bike Orienteering Introduction Bike orienteering (“Bike-o”) combines map reading and route planning as an extra dynamic to mountain bike racing. A large number of navigational “controls” (markers) are placed on the race course. The location for each of the controls is marked on a map. The idea is to visit as many controls points as possible within the time allotted. The person or team with the most points (or, if all controls are visited, the fastest time) wins. The navigation is not as difficult as in traditional foot orienteering—all controls are placed on trails—but the challenge is in route choice and being able to navigate at speed. Bike orienteering is identical in concept to the mountain bike segment commonly used in adventure racing. An example of how the map would appear is shown below. The controls are located in the center of the magenta circle, and a control number appears nearby. Controls can be worth 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 or 60 points, depending on how hard they are to get to, or how difficult the navigation is. The leading digit of the two-digit control number indicates the number of points—for example, control “26” would be worth 20 points. Map reading, route planning and navigational efficiency are key elements of Bike-O Each competitor or team will carry a punch card with the control numbers listed. When a control is reached, the marker will have a uniquely coded punch pattern—this is how the scorekeeper determines that you did indeed visit the control. -

Own Adventure

Adventure out Choose your own adventure Since the 1990s, adventure racing has taken off around the world with participants swimming, mountain biking, trail running and paddling in picturesque locations in national and regional parks. Accomplished athlete Morgan Marsh took part in the Eagle Bay Epic Adventure Race to find out if her years participating in triathlons and ironman events would hold her in good stead competing in the rugged outdoors. by Morgan Marsh s a tried and true Type A triathlete, it is always a bit of A a challenge to step out of my comfort zone and try something different. But 2020 certainly pushed us all out of our comfort zone, so why not extend that even further? Enter - the inaugural Eagle Bay Epic Adventure Race. ● Meelup Regional Park With only five weeks before race day, I signed up. Given I hadn’t been on my mountain bike since I completed the Cape to Cape Mountain Bike Race in 2017, nor attempted to paddle for almost two years, I wisely, albeit uncharacteristically, chose beginning of adventure racing since it to participate in the entry level short involved running, cycling and paddling course. elements. The short course consisted of a Either way, these events prompted the 13-kilometre mountain bike leg from world to take notice and adventure racing the scenic Eagle Bay Brewery through really started to take off in the 1990s. the flowing trails in Dunsborough to the Much like a triathlon, adventure racing crystal blue waters edge of Dunn Bay, is broken into stages and the vast majority then a 1.2-kilometre ocean swim, followed of adventure races include a minimum by a five-kilometre paddle and finishing of trail running, mountain biking and a with an eight-kilometre trail run through paddling event.